Every song on the Billboard Hot 100 chart is there for a reason. Regardless of genre, these songs share particular features that help them communicate to millions of listeners.

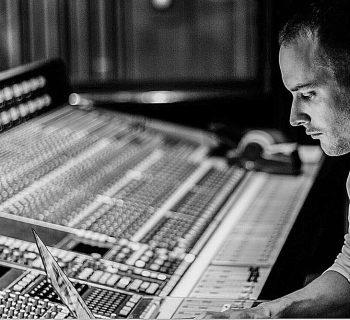

After 10 years as an engineer and producer at Westlake Recording Studios, I’ve worked on hundreds of tracks designed to break that chart. Michael Jackson’s record-setting album Thriller was recorded at Westlake, and we continue to work with chart-topping music from The Weeknd, Rihanna, One Direction, Adele and many others.

I’ve discovered there are often distinguishing factors that make hit songs more streamed, downloaded and consumed than their competition. If you apply what often works in hits songs to your music (within your own personal style and voice), it becomes more positioned to connect with a much greater audience.

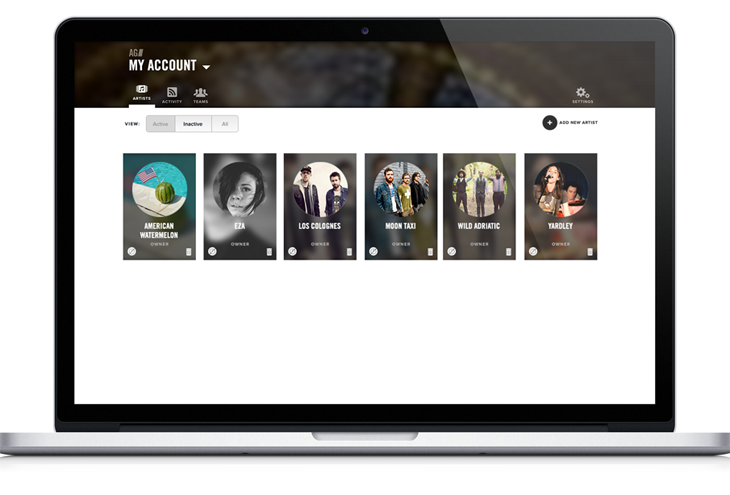

This is the premise of Westlake’s new Crē•8 Music Academy, which launches in January 2016. Based on what we see work in Westlake sessions every day, we are offering a 360 degree course for producers, songwriters and artists to create competitive sounds, songs and master recordings. I’ll briefly touch on three areas explored in our curriculum: building a song’s foundation, crafting melodies and mixing.

1. A Song’s Foundation––Rhythm Or Melody?

Most popular songs have either a primarily melodic or rhythmic foundation. The Weeknd’s current hit, “The Hills,” is an example of a track based on a melodic foundation, including a steady chord progression and a radio-friendly hook. “Locked Away,” which was tracked at Westlake by

R. City and features Adam Levine, has a rhythmic foundation. Don’t be fooled by its five-chord progression: the song would feel entirely different without the reggeton backbeat, whereas “The Hills” would feel almost identical, even with a different drum groove underneath.

For a melodic track, songwriters and artists often collaborate for hours around a piano or acoustic guitar to find that perfect hook. A demo is created and ultimately fleshed-out with a producer. Throughout the arrangement, the production stays centered around this melody of the song.

On the other hand, a rhythmic foundation is built around a drum groove with a great “pocket”. This kind of track may “open up” to additional chords or melody in the hook, or stay simple throughout, but it’s always fueled by the underlying rhythm. The arrangement of rhythmic tracks, rather than being driven by a melody that lifts and rises, is created through differences in rhythmic complexity and density. Verse drums and percussion should be solid, steady and basic; B-Section and hook drums can introduce new sounds and complexity.

To summarize: successful songs in today’s market usually have EITHER a rhythmic or a melodic foundation, not both.

Tips:

• Choose a melodic or rhythmic focus in the beginning to simplify the writing process.

• Fill space in a simple progression with either a strong melody or a strong rhythm.

• For rhythmic productions, create a lift through changes in rhythmic density rather than in melody.

2. Crafting Melodies

Melody in popular music has two main aspects––“topline” (lyrics plus melody) and melodies within the music itself. Many successful songwriters focus exclusively on topline, the best earning large retainers and hefty mechanical/performance royalties.

Songs meant for commerce tend towards a particular structure in their topline melody. The verse centers around the root, second or third of the scale. The B-Section (pre-chorus) leans on the third, fourth or fifth. The hook (chorus) melodies rise to focus on the fifth, octave or just above the octave, creating a sense of lifting or soaring.

If your verse melody emphasizes the root, try moving to something that centers around the third in the B-section, and the fifth in the hook. These notes can serve as a subtle “anchor” for your melody as it moves through the song, thus they may appear a few more times than any other note in their respective section. Alternatively, if the verse emphasizes the third, move up to the fifth during the B-section and the octave for the hook.You may be shocked at the impact such a seemingly simple idea can have on a song. If it happens more often than not on hit songs, why not give it a try?

For some examples of this concept, check out Justin Bieber’s recent hit “What Do You Mean?,” which centers around the root (Ab) throughout the entire verse. “Drag Me Down” by One Direction hovers around the root (C) in the verse, moving up to the fifth (G). “Photograph” by Ed Sheeran is in E major and centers around the third in the verse before rocketing up into his falsetto in the chorus.

The second aspect of melody is the arrangement. Hard rule: track melodies (guitar fills, synth leads) should never interfere with the topline. Instead they should weave in and out of the topline, resting and re-entering, providing a feeling of countermelody.

3. Mixing

The key here is to identify the few instrument or vocal elements that define the song. Mix those elements by themselves, applying effects and balancing levels. Leave the other tracks muted. Seriously. After the foundation is constructed, other elements of the mix will fall in place more easily.

For example, if the foundation is kick/snare/bass/lead vox, don’t adjust the kick while blending the guitar. Instead, mix the foundation first, then adjust the guitar around the kick. The sound of the guitar shouldn’t be sacrificed, just blended around the kick. If your foundation is weak or unstable everything will come crashing down. Take your time.

If you are targeting the commercial music market and want to refine your writing, production, mixing and mastering skills, contact Crē•8 Music Academy at 323-851-9908 or cre8info@cre8musicacademy.com to request a free music assessment and tour of our facilities.

DOUG FENSKE is the Director of Education of Crē•8 Music Academy at Westlake Recording Studios. A Grammy-nominated engineer-producer, Fenske has worked on multiple platinum and gold releases. For information about Crē•8 Music Academy’s 30-day and 10-week intensive music production program visit cre8musicacademy.com.