The Recording Academy was formed in 1957. By the spring of 1959, the world was introduced to a new honor: the Grammy. The 62nd annual Grammy Awards took place on Sunday, Jan. 26 at the Los Angeles Staples Center, which seems destined to be its home for the foreseeable future. As is typical of the evening, it was attended by a rich array of artists, industry folk and music fans.

On stage there were dazzling lights, racy regalia and stellar performances. But of course the show that the world hears is made possible by a relatively small but seasoned crew of behind-the-scenes audio adventurers. Without their crucial contributions, the Grammys would hit about as hard as a non-alcoholic shot of whiskey.

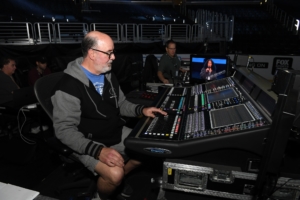

As a live event, it would seem that audio mixers must make the best of the performance they’re given. But there are, in fact, loopholes to their limitations. “For rehearsals, we’ll record and do a mix and then we can play that back and fine-tune it along with the artist,” explains John Harris, co-Music Mixer on the show. “We get it just right and store that as a static position on the desk. Then when the show comes around, we have all of our notes and cues. You can’t automate anything live.” This is all accomplished in two identical trucks stationed just outside of the Staples Center. 2020 marks Harris’ thirtieth year as a warrior with the Grammys’ audio army.

One of the biggest challenges this year was that there were twenty-plus artists included in “I Sing the Body Electric,” the show’s finale. “Everybody has different little pieces and they’re all in different parts of the room,” Harris observes. “I have one with Lil Nas [X] and Billy Ray Cyrus and they have a whole house on the stage. As it rotates, the artists walk through rooms and then there are another bunch of artists. Each has its own challenges. Nobody comes with just a band, sets up, does their song and says goodbye.”

Ron Reaves has served as front-of-house engineer with the Grammys for nineteen years. Outsiders may imagine that show-night is a debilitating mix of nerves, anxiety and even existential angst. But for him, that’s anything but the case. “It’s the best day of my year,” he asserts. “The performances are always great and off the charts. I once told one of the executive producers that I’d do the three hours of mixing for free. It’s all the other stuff that I charge for.”

Technology changes almost daily but that doesn’t mean that it’s deployed with as much haste. Sometimes adoption is slow. “In the world of live television, we’re kind of the last to embrace new technologies,” says audio engineer Steve Anderson, who’s worked intermittently with the Grammys since 1986. “Failures mean a little more in this setting than they do in a theater where you can delay the start of show. This is the first year that we’ve used Dante distribution on all of the RFs. In the event of trouble, our first fallback is analog equipment that runs at the same time. The full analog structure is still in place. Our voices are pretty analog so we’ll always have it on some level. Up until two years ago we still had copper between us and the transmission truck.” Dante is a software, hardware and network protocol combination that conveys uncompressed, multi-channel, low-latency digital audio over a network. Development on it began in 2003.

Behind all of the guitars, glitter and glamour stands MusiCares, the charitable arm of the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences. Incorporated in 1993, it provides critical aid to members of the music community. “It’s a safety net for all music people,” explains Ryan Donahue with the organization. “We have artists sign various things during the soundchecks on the day of the show and then auction everything online. Each artist also signs a page of the green-room book, which is also sold at auction.” In the past, it’s fetched between $5,000 and $10,000. As of February 2 with three days to go, the bid had climbed to $2,550.

The great thing about technology advances is that it enables the Grammys to become greater and grander every year. Few would be surprised if in 2030 the 2020 Grammys are remembered as a simple, few-frills show, comparatively. But for now, it remains the best in the business, in large part due to the expertise of its largely-unseen engineers.