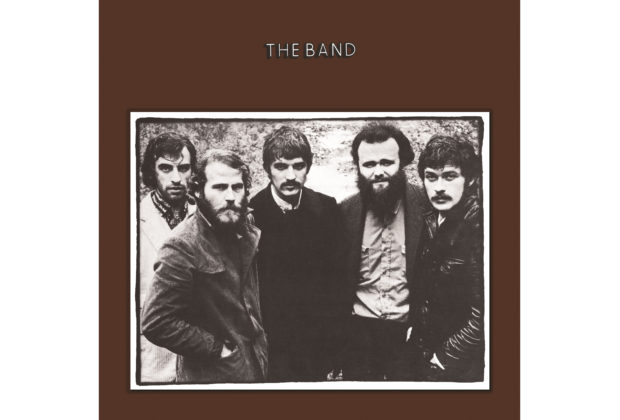

When The Band’s seminal eponymous second album was released 50 years ago on Sept. 22, 1969, not much more was known about the reclusive group than when they released their landmark debut, Music From Big Pink to widespread critical praise and bewilderment, just the year before. The band, made up of four Canadians and one American, was still shrouded in mystery, allowing for listeners and the music press to let their imaginations run wild about who these men were and what this music was that sounded unlike anything else happening at the close of the psychedelic ‘60s.

Dressed like 19th century fire-and-brimstone preachers and singing rustic, sepia-toned songs about America and the deep south, The Band—Garth Hudson (keyboards, piano, horn), Levon Helm (drums, vocals, mandolin), Richard Manuel (keyboards, vocals, drums), Rick Danko (bass, vocals, fiddle) and Robbie Robertson (guitar, piano, vocals)—was an enigma, unlike any group that came before or after. And their self-titled "Brown Album," as it would lovingly be called, cemented their status as one of the most exciting and revolutionary bands in years, on the strength of now-classic songs like “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down,” “Up On Cripple Creek” and “Rag Mama Rag.”

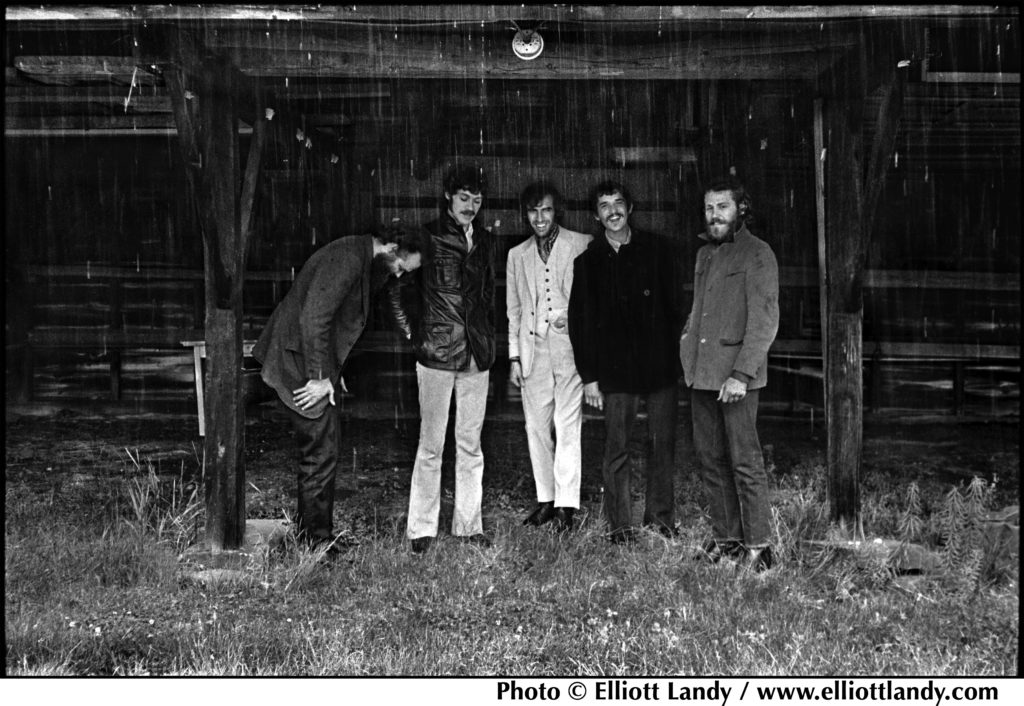

After much searching, we found the perfect spot right outside their window. Or did it find us? Levon and Rick’s yard. Woodstock, NY, ’68

Photo by Elliott Landy

On Nov. 15, Capitol/UMe will celebrate The Band’s pioneering self-titled album with a suite of newly remixed and expanded 50th Anniversary Edition packages, including a Super Deluxe 2CD/Blu-ray/2LP/7-inch vinyl boxed set with a hardbound book; 2CD, digital, 180-gram 2LP black vinyl, and limited edition 180-gram 2LP “tiger’s eye” color vinyl packages.

All the Anniversary Edition releases were overseen by Robertson and feature a new stereo mix by Bob Clearmountain from the original multi-track masters, similar to the acclaimed 50th-anniversary collections of last year’s Music From Big Pink releases. The 50th Anniversary Edition’s CD, digital, and box set configurations also include 13 outtakes, featuring six previously unreleased outtakes and alternate recordings from The Band sessions, as well as The Band’s legendary Woodstock performance, which has never been officially released.

Exclusively for the box set, Clearmountain has also created a new 5.1 surround mix for the album and bonus tracks, presented on Blu-ray with the new stereo, both in high-resolution audio (96kHz/24bit). All the new audio mixes have been mastered by Bob Ludwig at Gateway Mastering. The box set also includes an exclusive reproduction of The Band’s 1969 7-inch vinyl single for “Rag Mama Rag” / “The Unfaithful Servant” in their new stereo mixes and a hardbound book with an extensive, illuminating new essay by author and music critic Anthony DeCurtis and classic photos by Elliott Landy which have had an inimitable influence on rock and roll. For the album’s new vinyl editions, Chris Bellman cut the vinyl lacquers for the album’s new stereo mix at 45 rpm at Bernie Grundman Mastering, expanding the album’s vinyl footprint from one LP to two.

Clearmountain and Robertson’s approach to remixing the beloved album was done with the utmost care and respect for the music and what The Band represents. “The idea was to take you deeper inside the music, but this album is homemade,” Robertson says in the liner notes. “You can’t touch up a painting. It has nothing to do with what you get when you go into a recording studio.” When he expressed his concerns to Clearmountain, the renowned engineer and producer reassured him:

“We’re just trying to overcome the original technological limitations in order to bring you closer into the room,” he explained. “I’m going to do everything in my power not to get in the way of this music at all.” The result is a new mix that allows listeners to hear these classic songs in stunning, and oftentimes startling, clarity, packing more of a sonic and emotional punch than ever before. The included early and alternate versions offer fans the ability to hear the evolution of these tracks or as Robertson says, “That’s us trying to teach ourselves how to play these songs.”

Released in 1968, The Band’s game-changing debut album, Music from Big Pink, seemed to spring from nowhere and everywhere. Drawing from the American roots music panoply of country, blues, R&B, gospel, soul, rockabilly, the honking tenor sax tradition, hymns, funeral dirges, brass band music, folk, and rock & roll, The Band forged a timeless new style that forever changed the course of popular music.

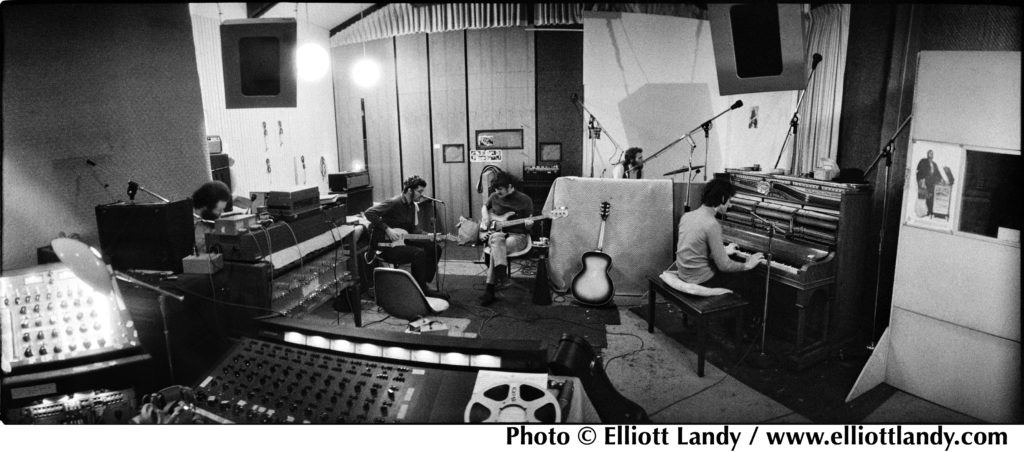

Shortly after the release of Music From Big Pink the members of The Band relocated to Los Angeles to record their follow up album. Searching for the same clubhouse vibe they had at Big Pink, they eschewed a traditional studio and moved into a house in the Hollywood Hills that had previously been owned by Sammy Davis Jr. The place had enough bedrooms that the group could reside there with their families and a pool house where they set up the studio.

While Capitol Records was dumbfounded the guys didn’t want to record in one of their state-of-the-art studios down the street, they ultimately relented and paid for the shipment of their equipment across the country. Recording here was not without its obstacles as getting an upright piano up to the house proved trying and since they were in a residential neighborhood, the pool house needed to be soundproofed from the outside, which was quite a sight.

Following dinner together with their families in the main house, The Band, joined by co-producer John Simon who helped shape their sound, as on their debut, would shuffle off to their makeshift studio to write and record their masterpiece, working through the night and stopping around dawn. Listening to these dusty, rural songs, it’s hard to believe they weren’t written in the Appalachian Mountains but instead perched up in the hills overlooking Los Angeles’ sprawling, smoggy metropolis.

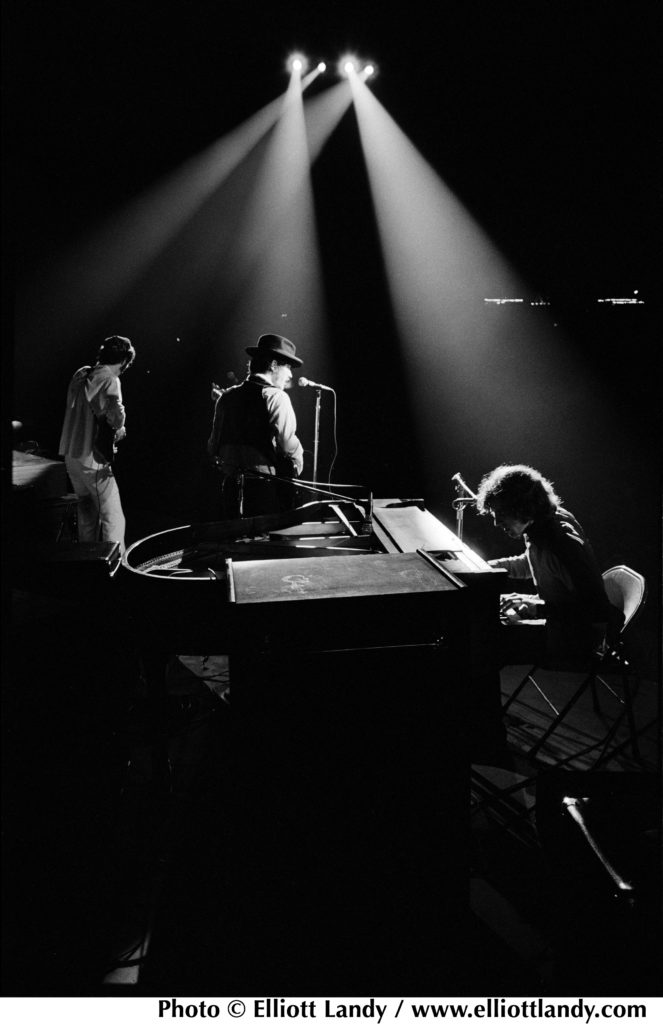

Robbie in the center, Richard at the piano, rehearsing at Richard and Garth’s house on Spencer Road. Woodstock, NY, ’68. Photo by Elliott Landy

In 1976 I attended The Last Waltz, the final show by The Band at the Winterland venue in San Francisco.

During I975, 1978 and 2017 I interviewed members of The Band.

In November 2018, Sterling/Barnes and Noble published The Story of The Band From Big Pink to The Last Waltz a book I wrote with my brother Kenneth.

In my 1975 interview with Robbie Robertson for Crawdaddy! magazine I asked Robbie about the double keyboard combination of piano and organ. I wondered if guitarist Robbie ever felt suffocated by this format.

“No. I play as much as I want to play. No one is telling me, ‘Listen, you’re playing too much.’ That’s my own decision. That’s how much I prefer to do. When I hear other people play a lot more than required I find it really drivel and there’s nothing in this fuckin’ wide world that’s going to do anything for the song; I don’t care. I like a good guitar part where it adds something, has a nice place and is a nice solo. Not too much, not too little. But I think as time goes on it just takes different proportions, and too much is unnecessary.”

Robertson’s guitar theory seems to simply extend his basic life philosophy of unhurried discipline.

Or, as Bob Dylan said when he called to talk about Robbie for the magazine: “Listen to his guitar playing. That’s all you have to know about him.”

In 2017 I interviewed Robertson for Record Collector News about The Band.

“Before Big Pink, I had had this dream of having a workshop. A place. A sanctuary where we could go into the privacy of our own world and do something and not be on somebody else’s lawn, to really be in our own environment, let alone away from studio union breaks. We go into a studio and the guy is like, ‘Well, it’s almost 4:00 p.m.…’ So all of these things are playing into it a little. Although the experience in the studio of recording Music From Big Pink was fabulous.

“The producer John Simon was great and the engineers were great at Phil Ramone’s A&R Recording, but the idea of having this private sanctuary and that it would have its own sound, its own sound and its own flavor. That’s where that Les Paul thing came back into the picture.

“It would be like Chess. We could have our own one. And it would not sound like any of these other places. Going into somebody’s environment and then saying, ‘You go over there. You sit here. And we’re gonna use this kind of microphone on you.’ I thought that was what you did with somebody else. ‘I feel like I’m getting seconds here.’

“I was thankful for that period of time too. Because it was now a period where an artist wanted to something that A&R guys like [Capitol Records engineer and staff producer] John Palladino had nothing to do with the music. He was never there when we recorded. No intrusion.

“So when I said, ‘we want to do this thing that started in the basement of Big Pink. We want to bring the equipment to us in our own atmosphere. And we want to record at whatever time we feel the spirit. We don’t want to be on somebody’s clock,’ John was like, ‘OK.’ ‘We just need the equipment to come to us.’ And he had to kind of go along with it, you know, but he didn’t understand it.

“We came to do it in Hollywood because it was too cold in Woodstock. [Laughs.] And we were from Canada. So we knew cold and we knew when to get out of the way. So we thought, ‘Wouldn’t it be wonderful to go and do this thing and go outside, where it feels beautiful and sunny and everywhere else it’s stormy.’ It was a good feeling inside and we felt we were getting away with something.”

Here’s a regional fact that informed the sound of The Band. The drum kit with wooden rims that Levon Helm used on the album was found in Hollywood on Santa Monica Blvd. at a pawn shop.

In 2018 I spoke with drummer Jim Keltner who was invited to a recording session in spring 1969 for a track appearing on The Band.

“I was playing with the Charlie Smalls Trio. Wilton Felder was the bass player. Charlie sang and played piano. We had two great girl singers. Charlie later wrote the big Broadway hit, The Wiz, which they later made into a movie.

“We worked the Daisy Club in Beverly Hills a few times. We were going to play the evening of [June 5, 1968] for a victory party when Robert F. Kennedy got shot.

“I met The Band through my dear friend and the amazing bassist, Carl Radle. We were with Gary Lewis & the Playboys. Leon Russell was the producer and arranger. We were all from Tulsa, OK.

“Carl took me up to Sammy Davis Jr.’s house high up in the Hollywood Hills where the Band were doing their second album for Capitol. They had a studio set up in the pool house. I think they had an eight-track machine. Carl knew Levon and the guys and he was the one who turned me on to the Music From Big Pink album. That album blew my mind. I listened to it all the time. I thought they were all Southern guys. And it was kind of a shock when I met them. Levon was the only guy from the South.

“If you are a singing drummer you have a great advantage. I’ve always played to the vocal and I found out that Ringo and countless other drummers, I’m sure, do as well.

“Levon was able to push or pull the groove any way he felt it by singing and playing at the same time. The way he felt space was magnificent. His biggest influences were the blues bands he heard as a young man. The geniuses from the Delta and around where he was from.

“So to hear that Big Pink LP and then go to a couple of tracking sessions in Hollywood for their next album and to hear Levon singing and playing with one of the greatest singing bass players, Rick Danko, who always made me wanna cry. Such a sweet soulful voice. And Richard Manuel was the voice that sounded like it was coming straight from heaven. Garth Hudson creating a totally unique sound for the Band. His keyboards seemed to have a voice just as soulful and timeless as Rick and Richard’s. And, of course, those epic songs and perfectly formed guitar parts and solos of Robbie Robertson.

“I was in New York in July 1969 with Delaney and Bonnie. One night I ended up at the Hit Factory, I think, could have been A&R studios. John Simon and Robbie and the guys were mixing ‘The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down.’ They had recorded the track a few weeks earlier in Hollywood.

“I can’t even begin to describe what that scene was like. I was sitting in the back on a couch watching this happen. There were four or five pairs of hands all over the studio console. The song seeped into my soul so much so that later when I would hear it on the radio and remember that evening with those guys as they mixed I would just cry. It still gets to me when I hear it.

“Levon makes you believe this guy Virgil Kane and his deep Southern pride. I am so glad I met Levon as early on as I did. His goodhearted soulfulness helped change my outlook on music and people. I will never tire of hearing the Band play and sing those great songs.”

Besides the sessions at Sammy Davis, Jr’s converted studio, ‘Up on Cripple Creek,’ ‘Whispering Pines’ and ‘Jemima Surrender’ were cut in New York at The Hit Factory.

In 2018 I asked engineer/producer Richard Bosworth to discuss the Hit Factory.

“Jerry Ragovoy’s Hit Factory recording studio was located in Manhattan’s Times Square at 140 West 42nd Street and opened in 1968. It was the former site of the iconic Bell Sound recording studios. Bell Sound was one of the first independent studios, and many artists preferred it to the record company rooms. Buddy Holly, Dionne Warwick, the Lovin’ Spoonful, Ray Charles and Lloyd Price and many others made significant records there. Jazz pianist Bill Evans insisted on recording at Bell Sound. And in 1969, Led Zeppelin mixed their second album with Eddie Kramer when it was transitioning from Bell Sound to The Hit Factory.

Photo by Elliott Landy

The new expanded edition of The Band also incorporates the group’s August 1969 booking at the Woodstock Festival in Bethel, New York.

Michael Lang the concert promoter suggested to their manager, Albert Grossman that they close the Aug. 17 event. The Band were joined by Jefferson Airplane, the Who, Joe Cocker, Country Joe & the Fish, Janis Joplin, Johnny Winter, Ten Years After, Sly & the Family Stone, Blood, Sweat & Tears, Crosby, Stills, Nash (and Young), the Paul Butterfield Blues Band, Sha Na Na, and Jimi Hendrix.

“Woodstock. The ultimate calamity,” the Grateful Dead’s Jerry Garcia reminisced to me in a 1976 interview for the defunct Melody Maker. “It was raining and it got dark and we went on. There was maximum confusion going on about sound logistics. Really weird. Plus I was high, of course. And I went onstage in a state of confusion. The stage had sheet metal on it. It’s wet, and I’m getting incredible shocks from my guitar.

“It’s dark, and you don’t see any audience, but 400,000 people are out there. Then, somebody says the stage is about to collapse. I’m standing there in the middle of this trying to play music. Then they turn on the lights, and they’re a mile away. Monster super troopers. Totally blinding and you can’t see anything at all.

“Here’s this energy and everything is horribly out of tune. ’Cause it’s all wet, damp and humid. It was humbling. [Laughs.] That was a total disaster from our point of view. We played probably the worst set of our career. I’d like that one erased from the books.”

“It was about 10:00 p.m. Sunday night when The Band took the stage and in addition to the dampness it got very cold,” remembered concert attendee Richard Bosworth.

“Musical instruments and musicians’ hands can be challenged by that kind of weather. Guitars go out of tune and bodies stiffen up, and that’s how the Band came off at Woodstock. Stiff and wooden. Of course the audience was under the effects of the weather as well and we were pretty uncomfortable at that point.

“I was very close and centered to the stage and one noticeable element was the unique way the group set up. Garth Hudson was in the center on a high riser, normally the place the drums would be, and Levon was far right facing stage right, not facing the crowd. Richard Manuel was far left facing stage left and Rick and Robbie were in the center below Garth.

“I had been very excited about seeing them. Music From Big Pink was such a world-changing record in 1968, and their second album wouldn’t be released until the following month and they didn’t play anything from that. I had high expectations but was disappointed by the Band’s perfunctory performance. I’ve since seen video where they play with great feeling and fire, but at Woodstock that was not the case.”

For the first time, this 11-song performance can now be heard in full as part of the Super Deluxe boxed set. Being only The Band’s second show, the concert focuses heavily on songs from Music From Big Pink, including “The Weight,” “Long Black Veil,” “Tears Of Rage,” “Chest Fever” and “This Wheel’s On Fire,” as well as their rendition of The Four Tops’ “Loving You Is Sweeter Than Ever.”

“I’ll tell you something. It doesn’t matter if there’s 30 or 300,000—once you get in front of people, you have to do something,” Robertson told me in a 1975 interview for Crawdaddy! “The festivals are for people to get together. Who is playing is secondary.

“Anytime we’ve done those things, we’ve never really felt natural about doing it. We played the large dates because some terrific people were involved or we admired the other acts and they asked us to. We’re a puppet show in the distance, and the music is an excuse.”

The Band explores America’s thorny history through indelible archetypes—“The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down” refers to Union cavalry officer George Stoneman’s attack on southwestern Virginia in the last days of the Civil War, “King Harvest (Has Surely Come)” is sung from the perspective of a poverty-stricken farmer who becomes a “union man” to his disappointment, and “Up on Cripple Creek” is about a truck driver’s debauched time with a local girl in Lake Charles, Louisiana.

It’s fitting then that the first song the group recorded for The Band was “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down,” a Civil War story that was inspired by a visit Robertson made to Helm’s family in Marvell, Arkansas. During one of their talks, Helm’s father insisted to Robertson that “The South will rise again!” “I felt that I understood something about Levon from meeting his family,” Robertson says. “I wanted to write a song that he could sing better than anyone in the world.” The song imbues the people of the South with a forlorn dignity much in contrast to their stereotypical portrayals in popular culture – and Helm’s heart-rending vocal tells the song’s story with consummate grace.

This was not subject matter that other songwriters were mining from at the time and illustrated how The Band’s primary songwriter, Robertson, did not draw inspiration from typical rock sources, instead pulling from history and his love of classic films and screenplays.

I asked Robbie Robertson in our 1975 Crawdaddy! interview about crafting autobiographical songs and employing a third person narrative in some of his tunes heard on The Band.

“I just think it’s part of storytelling,” Robertson reinforced. “It isn’t anything to put the songs in the third person. Sometimes when you get that little detachment you can write about more. I’m Canadian and I wrote the song about the Civil War [‘The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down’]. I didn’t know the story and it fascinated me. Everyone else took it for granted—they read about it in history class. When it’s strictly about yourself you’re ‘not allowed to deal with fiction.’ So it’s something that opens the gates a little bit.”

Inspired by his decades of creating and composing music for film and filled with an enthralling set of songs exploring the darker corridors of human nature, Robbie Robertson’s aptly titled, evocative new solo album Sinematic was released on Sept. 20 via UMe.

The 13-song self-produced collection is Robertson’s first new studio album since 2011’s introspective How To Become Clairvoyant.

For his new album, Robertson drew inspiration from his recent film score writing and recording for director Martin Scorsese’s eagerly anticipated organized crime epic The Irishman, as well as the forthcoming feature documentary film, Once We Were Brothers: Robbie Robertson and The Band, based on his 2016 New York Times bestselling memoir Testimony.

The documentary was premiered Sept. 5 as the Opening Night Gala Presentation for the 44th Toronto International Film Festival. 2020 theatrical screenings are being arranged for the United States.

“I was working on music for The Irishman and working on the documentary, and these things were bleeding into each other,” says Robertson of the impetus for Sinematic.

“I could see a path. Ideas for songs about haunting and violent and beautiful things were swirling together like a movie. You follow that sound and it all starts to take shape right in front of your ears. At some point, I started referring to it as ‘Peckinpah Rock’,” a nod, Robertson says, to Sam Peckinpah, the late director of such violent Westerns as The Wild Bunch.

Photo by Elliott Landy

Inspired by Robertson’s acclaimed 2016 autobiography, Testimony, director Daniel Roher’s Once We Were Brothers documentary explores Robertson’s young life and the creation of The Band, one of the most influential groups in the history of popular music. The compelling film blends rare archival footage, photography, iconic songs, and interviews with many of Robertson’s friends and collaborators, including Martin Scorsese, Bruce Springsteen, Eric Clapton, Van Morrison, Peter Gabriel, Taj Mahal, Dominique Robertson, and Ronnie Hawkins.

Made in conjunction with Imagine Documentaries, White Pine Pictures, Bell Media Studios, and Universal Music Canada’s Shed Creative, the project is executive produced by Martin Scorsese; Imagine Entertainment chairmen Brian Grazer and Ron Howard; Justin Wilkes and Sara Bernstein for Imagine Documentaries; White Pines Pictures’ president Peter Raymont, and COO Steve Ord; Bell Media president, Randy Lennox; Jared Levine; Michael Levine; Universal Music Canada president and CEO Jeffrey Remedios; and Shed Creative’s managing director Dave Harris. The film is produced by Andrew Munger, Stephen Paniccia, Sam Sutherland, and Lana Belle Mauro.

Harvey Kubernik is an award-winning author of 15 books. His literary music anthology Inside Cave Hollywood: The Harvey Kubernik Music InnerViews and InterViews Collection Vol. 1, was published in December 2017, by Cave Hollywood. Kubernik’s The Doors Summer’s Gone was published by Other World Cottage Industries in February 2018.

Kubernik’s The Doors: Summer's Gone has been nominated for the 2019 Association for Recorded Sound Collections Awards for Excellence in Historical Recorded Sound Research.

During November 2018, Sterling/Barnes and Noble published Kubernik’s The Story of The Band From Big Pink to the Last Waltz.

Harvey Kubernik’s 1995 interview, Berry Gordy: A Conversation With Mr. Motown is in The Pop, Rock & Soul Reader edited by David Brackett was published in 2019 by Oxford University Press.

In 2019 Kubernik is researching a book on Jimi Hendrix which is scheduled for publication last quarter of 2020.

This century Kubernik penned the liner note booklets to the CD re-releases of Carole King’s Tapestry, Allen Ginsberg’s Kaddish, Elvis Presley The ’68 Comeback Special and The Ramones’ End of the Century.

In November 2006, Kubernik was a featured speaker discussing audiotape preservation and archiving at special hearings called by The Library of Congress and held in Hollywood, CA).