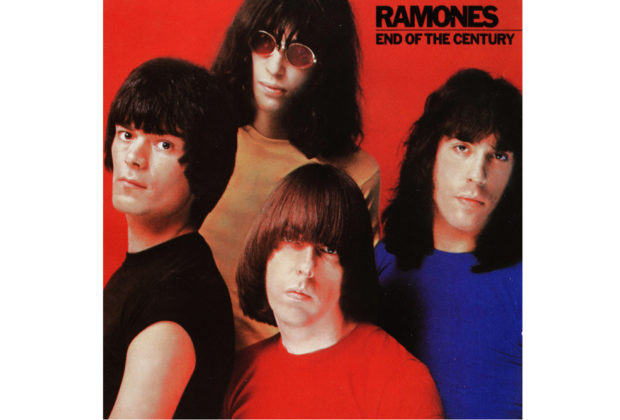

With the recently released deluxe edition of the 1979 Ramones’ tour album, It’s Alive, and the planned last quarter 2019/early 2020 40th anniversary of the original Phil Spector-produced End of the Century, with producer Rick Rubin who is involved for an expanded reissue of this initial pressing, it is time to re-visit End of the Century, cut at the landmark Gold Star Recording Studios in Hollywood.

I was in attendance at just about all End of the Century sessions as a food runner, and on occasion, supplied handclaps and percussion, and was credited on a couple of tracks.

I eventually penned the liner notes for a 2002 Rhino Records repackage of the album. It was an assignment that came just after ownership changes at the label. The late great Gary Stewart graciously insisted that I do them knowing I chronicled the Ramones/Spector relationship for the London-based Melody Maker.

During August 2019, I saw the opening night world premiere of 33 1/3-House of Dreams, the musical stage show about Gold Star co-owner/engineer Stan Ross at the San Diego Repertory Lyceum Stage Theatre written by Jonathan Rosenberg and Brad Ross, son of Stan Ross.

Ross and his partner Dave Gold owned Gold Star which garnered more Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) Songs of The Century and Grammy Hall of Fame winners than any other independent studio in America. Gold Star was built in 1950 and lasted until 1984 at 6252 Santa Monica Blvd until a fire destroyed the property in March 1984.

There were many show-stopping moments in 33 1/3 House of Dreams including a revealing tension-filled dramatic scene between actors portraying Phil Spector, the Ramones and a very alarmed Gold Star staff.

But what brought the Ramones, Phil Spector and Gold Star together? The week before he began the Ramones album, Spector helmed a production of Jonathan and Andy Paley’s “Baby, Let’s Stick Together” done at literally the last formal “Wrecking Crew” session at the famed studio. Ray Pohlman, Hal Blaine, Tommy Tedesco, Jay Migliori, Jim Keltner, Julius Wechter, Steve Douglas, Barry Goldberg and Dan and David Kessel were on the date. Rodney Bingenheimer, Phil Seymour and I provided percussion on the recording. Darlene Love and Joey Ramone also came to the session.

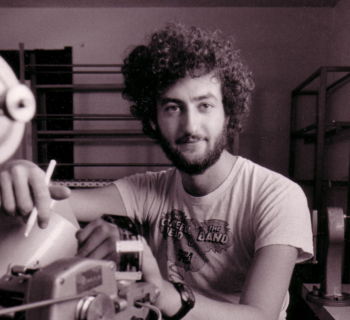

During 1979, the week before the Ramones flew to Los Angeles for these Spector sessions, the band recorded five demos with engineer/producer/guitarist Ed Stasium, which were included on the Rhino/WMG distributed 2002 re-release.

“These were the first demos I did with the Ramones,” remembers Stasium. “We did them all in one day. Johnny ran it like the military, all prepared and ready to go. We cut them on a Thursday, and the next week we were in Hollywood rehearsing at Studio Instrument Rentals for four days before End Of The Century started with Phil.”

On May 1, 1979, the Ramones entered Gold Star Recording Studios in Hollywood, California, with producer Phil Spector. I was there, covering the action for Melody Maker.

End Of The Century brought the band together with one of the true architects of sonic studio moxie, Phil Spector, and was cut at a studio that had seen not only Spector’s finest work but also awe-inspiring endeavors by the likes of Herb Alpert & The Tijuana Brass, Buffalo Springfield, Brian Wilson and the Beach Boys, Iron Butterfly, Chris Montez, Jack Nitzsche, Sonny & Cher, and Eddie Cochran, among others.

The Ramones made their way to Spector and the legendary Gold Star world via several denizens of the Los Angeles music scene. The band had played backing tracks on a cover of “Surfin’ Safari” for Rodney & The Brunettes, deejay Rodney Bingenheimer’s side project. The producers were local duo and Spector pals Dan and David Kessel.

Throughout the 1970s, the Kessel’s guitar work, electric and acoustic, could be found on Spector productions and albums by Harry Nilsson, Cher, John Lennon, Darlene Love, Dion, the Paley Brothers, and Leonard Cohen.

During 1977, when Spector was working with Leonard Cohen on his album Death of a Ladies’ Man, Leonard and I went to see Allen Ginsberg do a poetry reading at Doug Weston’s Troubadour club in West Hollywood on Santa Monica Blvd. and later caught a Ramones’ set at The Starwood club on the same street.

In 1978, Dan and David Kessel produced and arranged the Ramones song, “Slug” (available on the CDs All the Stuff (And More), Vol. 2, and Rocket to Russia, as well as on Rhino’s 2005 box set Weird Tales of the Ramones).

“Dan and I got on the phone to Phil,” David Kessel recalls, “and played Phil some of what we had produced with the Ramones. His immediate reply was that we should pick up some pizzas and bring the Ramones over to his mansion in Beverly Hills. That was truly a happening night.”

Bingenheimer and the Kessel brothers then brought Spector to see a Ramones show at the famed Whisky A Go Go. I met them at the venue. It seemed like a moment that was bookended for history.

In an interview with veteran music journalist Jaan Uhelszki, Joey Ramone explained Spector wanted to record him solo. “I guess the way it originally came about is Phil wanted to do a solo record with me, but it was a little premature. This was only our fifth record,” he told Uhelszki. “It excited me because he loved my voice. He would say to me, ‘I’m going to make you the new Buddy Holly.’ As for the rest of the Ramones, they thought he was trying to steal me away.”

Recording with Spector, and tolerating the maestro’s demanding hours, resulted in the logical next step in the Ramones’ musical evolution. Following the group’s initial experimentation on Road To Ruin—which featured 12-string acoustic guitars in the mix, and what, for the Ramones, amounted to a genuine ballad with the Sonny Bono/Jack Nitzsche ’60s classic “Needles And Pins”—the progression to End Of The Century was the culmination of the band’s desire to make a great rock ’n’ roll record.

Larry Levine, Stan Ross’ cousin, was one of the house engineers at Gold Star and a crucial component in Spector’s “Wall of Sound” audio endeavors.

Larry engineered sessions for Eddie Cochran, the Beach Boys, Sonny and Cher, Herb Alpert & the Tijuana Brass, Dr. John, and with Spector in the late '70s, albums by Leonard Cohen and the Ramones’ End Of The Century, with Boris Menart and assisted by Bruce Gold.

“As far as the room sound and the drum sound went, because the rooms were small, with low ceilings, the drum sound, unlike other studios with isolation, your drums sounded the way you wanted them to sound,” mentioned Larry to me in a 2002 interview. “They would change accordingly to whatever leakage was involved.

“As a matter of fact, Phil once said to me the bane of his recording existence was the drum sound. A lot of people attribute the echo to what Phil was doing. The echo enhanced the melding of the ‘Wall of Sound,’ but it didn’t create it. Within the room itself, all of this was happening and the echo was glue that kept it together,” suggested Larry.

“I used to have a theory [that] part of the reason we took so long in actually recording the songs was that Phil needed to tire out the musicians—[until] they weren’t playing as individuals, but would meld into the sound that Phil had in his head.”

Marky Ramone, Phil Spector, David Kessel

The opening blast of “Do You Remember Rock ’N’ Roll Radio?” is the perfect balance between Spector’s “Wall of Sound” and the Ramones’ Wall of Buzz. This is the one track on the album where the fusion of the Ramones’ and Spector’s sensibilities exceed the burden of heightened expectations. The dark romanticism of the next song, “I’m Affected,” is driven home with loads of echo on Joey’s vocal and a menacing backing track from Spector and the band that underscores the track’s proclamations of love with a threat of violence.

On the sweeter side, echoes of The Beach Boys’ “In My Room” float through “Danny Says,” from its delicate, chiming guitars to the childlike intonations of Joey’s singing. The lyrics, dealing with “a typical day in the life” of the Ramones on tour and including numerous insider references, make this one a particular fan favorite.

“Chinese Rocks,” or “Chinese Rock,” as it has been documented over the decades, is a track co-written by Dee Dee and Richard Hell, which was originally given to the Heartbreakers to record.

“Dee Dee came to rehearsal with the song ‘Chinese Rocks,’” reminisced Johnny Ramone, “and we said, ‘Dee Dee, we’ve just written two songs similar to it…one was ‘Commando,' and I don’t remember what the other one was. But there were two songs that were very similar to it, and it was about dope, and I said, ‘We don’t sing about dope…we’ll just hold it’. And I think he got insulted by that, and went ahead and gave it to the Heartbreakers. Then I heard the Heartbreakers version, and said, ‘Hey, that’s a really good song.’ So that’s when I realized that it was a good song, and we incorporated it into our set.”

The record’s fifth selection, “The Return of Jackie and Judy,” is a musical sequel to “Judy Is a Punk” from the Ramones’ debut album. Rodney Bingenheimer, Phast Phreddie, Maria Montoya, Jeff Morrison and myself all contributed handclaps which we also did on “Do You Remember Rock ‘N’ Roll Radio?”

Revisiting the past is always a dicey proposition, and the song’s a pale carbon copy of the prototype. Drummer Marky Ramone agrees: “I don’t like, ya know, stories that continue into another relation song that develops. I felt it was kind of corny.”

The album’s midway point and one of two tracks on the record co-written by Johnny and Dee Dee is “Let’s Go.” Perhaps an even better Ramones homage to the girl groups of the ’60s is “I Can’t Make It On Time.”

Another incredibly infectious track on the record is “This Ain’t Havana,” co-penned by Dee Dee and Johnny. It’s the album’s best example of the band’s celebrated sense of humor.

A re-recorded “Rock ’N’ Roll High School,” slotted in as the album’s tenth track, features fleshed-out production that loses some of the raw kick of the bare-bones original.

The last two cuts from the album, “All The Way” and “High Risk Insurance” round out End Of The Century in solid Ramones style. Surprisingly, Spector doesn’t tamper much with the basic guitar-bass-drums attack that the band was justifiably famous for, and they deliver a pair of straight-ahead rockers.

Spector was against recording anything he had previously done, but at the urging of the band and Sire Records label head Seymour Stein, Phil agreed to produce a cover of Barry/Greenwich/Spector’s “Baby, I Love You” for End Of The Century. The Ramones’ rendition, unfortunately, comes perilously close to disco to make for entirely comfortable listening for most of their fans; and the slick production and strings overwhelm the song’s natural charm. Consequently, it’s easily the most divisive and disliked song on the album.

Regarding “Baby, I Love You,” Johnny Ramone offers his point of view: “Yeah, I wanted to do a Phil Spector song. . . . I realized that it was a mistake, and to me it was the worst thing we’ve ever done in our career.

“But on ballads like ‘Danny Says’,” Johnny continues, more upbeat, “the production work is tremendous. On ‘Do You Remember Rock ’N’ Roll Radio?’ the production works. On some of the things it works, some of the things it doesn’t work. Because of the echo and reverb, I can’t separate; I like to distinguish the guitar from the bass guitar from the drums. I can’t distinguish the separation, because it’s muddy. That’s the sound,” kvetched Johnny.

“We had the album cover where we have no jackets on…I wasn’t happy. We took the picture without the leather jackets, and we should have never had done that, and then we took a picture with the leather jackets…

“The photographer…and Joey and Dee Dee said, ‘Maybe we’re not getting played because we have leather jackets on…let’s go with that picture.’ I was against that, and Mark was against that too, but they said Mark’s vote didn’t count. So it was two against one; it was a power struggle going on where Dee Dee and Joey were pals at one point, and that’s what was just happening, and Mark’s vote didn’t count, and we put the leather jacket photo on the inside sleeve.

“I thought it was selling out—this was our image, and we should stick with our image, and either sink or swim with it. I thought it was compromising and selling out. I didn’t want anyone coming up to me and saying, ‘You guys are selling out…’ And it had “Baby, I Love You” on it, too…so this was not a great period.

“Looking back, I’m glad I worked with Phil—I worked with a legend of rock & roll. The last things I know of that he’s done are the Ramones and the Beatles. . . . I’m proud to be part of his discography. . . . At the time I did it, it was very difficult, it was very stressful. But I’m still happy I did it.

“On stage, we did ‘Rock & Roll Radio’ always, from the time the album came out through the rest of our career. ‘Rock & Roll High School.’ ‘I’m Affected’ was in the repertoire for a while. ‘Chinese Rocks’ always stayed in the repertoire. ‘Danny Says’ we never did. It was a production song, it was never gonna work.

“The point it shows is when you’re making a record, it shows you can play, and you do what you’re supposed to do, and you do your part. But when you’re not communicating, that’s when it shows; you’re not writing together.

“Once Dee Dee and me started getting friendly again—I think on Subterranean Jungle, and more so on Too Tough To Die—we started working together.”

“The thing with Marky as a drummer was that he was very particular about the drum sounds and all of that,” stressed Dee Dee.

“But I think Joey was into a Keith Moon type drummer who would splash around the tom-toms and all that thing. But you know what? We didn’t bother Marky in the studio. He is a very self-willed person, and Johnny Ramone would show him a lot of parts. I wouldn’t worry about what everyone was doing, I would just lead it.

“Playing bass with the Ramones,” acknowledges Dee Dee, “I think I had a real good sense of time. That’s one thing. I could play bass like a drummer and I don’t know how other people do it, and they get better, or learn guitar tapping, whatever.

“There’s something about playing live that just makes you better. John and I had been playing for years and we played every night. Very few nights we didn’t play. We had a standard joke. We never rehearsed ‘cause we were always playing. To get the speed though, we had to warm up and we used to warm up in the dressing room with a trap kit, or fake drums, a Fender Champ amp. And that’s it. We would get the speed with the right hand going until finally, it grew to playing. Only playing downstrokes and then playing back. Speed, aggression, but if you are a singer/guitar player, you have to play up and down strokes or pause a little on the guitar. And John and I weren’t like vocal musicians. That’s what happened to us. We’re like a machine.

“On End Of The Century, I was using a white Fender Precision bass, with a red pickguard, maybe a 1977 model. A new one. I used to play a Danelectro, which the Ramones complained about, and I broke it one night, ya know. Because I had gotten the last set of Danelectro strings at Eddie Bell’s on 49th Street. They had their own short scales. The Danelectos’ bass scale, it was real small.

“Then I got a Fender Music Man or something like that, and they were upset, and stole it after a soundcheck. Then they got me Fred Smith’s bass of Television. This is like a 1964 Precision bass. ‘Better take care of this.’ I hated it and sold it for drugs, or something or I pawned it. I got a cheap new one.”

Dee Dee is equally intrigued by the EOTC recording, especially in hindsight: “Now I realize more and more, with time Joey’s voice had a real deep, deep part of the Ramones’ sound. And really that started with End Of The Century. I think Phil Spector and Joey were a great combination. Phil brought out the romanticism in Joey. He was like a romantic guy, and some of the songs and productions on End Of The Century pushed that. . . And ‘Baby, I Love You’ on End Of The Century—I never thought there would be a string section on a Ramones record, but I like it.

“Now I realize Phil had to spend time all that time with Joey. He was like a coach, ya know. It’s a process of discovery. . .I like romantic lush things. I wish for End Of The Century we would have done more things like with strings. We should have stopped touring and done another album with him.

“I wish I could turn back the hands of time to Gold Star and Phil and Joey would be there,” Dee Dee Ramone underlined. “Having that album is a good thing, is all I got to remember those days. They were really nice times. And Phil didn’t really pay much attention to me. I had a low concentration span. I think if you put me in someplace I would be trying to get out of it.

“You felt you were treading on history. Anybody would from my era. The Phil Spector sound was too powerful of a situation. Probably especially in Germany. It probably sounds more magnificent there. More out of reach or something

“The Ramones got a lot of new attention due to the End Of The Century album: Scotland, Holland, and Spain, we got a lot of TV shows, it got to be scary. We’d get to The Apollo Theater in Glasgow, Scotland, and we’d been playing it for years, then all of a sudden, all these very young girls were at the gig. I don’t think they’d see the Ramones, but they wanted to hear ‘Baby, I Love You.’ There was a video and it charted in Europe," he reiterated.

“I don’t think I knew how great the Ramones were in a way then. Also with End Of The Century, it was the first album we didn’t record in New York.

“I lived in Culver City around 1970,” disclosed Dee Dee. "I hitchhiked out here and when I got to L.A. first stop was Newport Beach. I met some guy, serviceman who picked me up. A jarhead who drove me into L.A.

“I got to L.A. and stayed to L.A. for five minutes, hitched up the Pacific Coast Highway to Big Sur for a month. Then I came back, and stayed in Culver City in the Washington Hotel. MGM Studios right down the street. Worked as a maintenance man at Helms Bakery. I might have been 18, and started at 12 midnight and hosed all the garbage dumps.

“I listened to the AM and FM radio dial. I had some history in Culver City. I used to go to thrift shops and look for 45’s and find good things. Boxes of singles. I found good R&B and rock & roll singles and pulled that same trick in New York in 1976. I had an apartment and the Cramps were living around there and hit the shops for tunes. Obviously, heard and found some records Phil Spector produced.

“I came to Hollywood all the time. I came to The Whisky even then. I saw Chicken Shack, who might have been on Sire Records? When I was living in L.A. and around Hollywood, it was at a time when everyone was getting a shag haircut. It was wonderful. It was a rock & roll town. I went to The Forum and The Santa Monica Civic Auditorium, Gazarri’s club. No wheels. I would hitchhike everywhere. I’m lucky I’m still alive.

“The songs on End Of The Century translated well on stage. ‘I’m Affected.’ We did the video on top of Joey’s roof of his apartment. Well, I think the End Of The Century is Joey’s Ramones album, that one or Pleasant Dreams. That’s his album. There’s nothing wrong with that.

"Of all the albums, the End Of The Century sticks out and shows a side to the Ramones that didn’t get developed and couldn’t have developed because of the obvious: we were a tight rhythmic band, although we’re not musical virtuosos, but what we did we did good. And you look at that cover and see that pop side to us that loved Rubber Soul by the Beatles, or the regimented pop groups. I think it’s nice to see the whole collection of albums and the covers, and that the whole thing ever existed."

“On this album, Mark was just so much more versatile and able to do so much more stuff,” remarked Johnny. “It was actually easier. We didn’t have Tommy’s guidance anymore—that was more of a problem because Tommy would intercede a lot.

“I didn’t feel like I was the same control I was usually in—playing what I wanted to play, and not worrying about anyone saying anything or making any comments.”

Drummer Marky Ramone is very proud of his End of the Century experience.

“I still listen to the record and try to understand what Phil did, which can baffle a lot of people. He’s like a conductor,” underscored Marky. “I was amazed how a certain sax can jump in, then a certain guitar tone would pop up . . . the way the roto-toms bounced off the walls to create that low-end hum after the end of the hit, which bounced right back onto the recording.

“The combination of the walls of sounds were like two 50 foot tidal waves hitting each other and how Phil’s influence made us sound like a '60s band with the Marshall’s, and all the later, heavier equipment, and of course, the Ramones’ sound.

“It was all fun and we did our jobs. For John and Dee Dee, it was a nightmare. They were used to working fast, and Phil worked at his own pace, which really frustrated John and Dee Dee because of how things were working. Personally, Phil was the producer and I went along with what he wanted ‘cause I knew of his experience.

“Gold Star had a great room. I was facing Phil and engineer Larry Levine while doing the LP. Phil and I would put a towel on the snare drum on certain songs, an old trick, especially on ‘I Can’t Make It On Time.’ I could see Phil grooving along with my tempo and I knew when he did that he was liking it! Me, Dee Dee and Johnny would play together then Ed Stasium would overdub some leads. We knew our vibe real well.

“I like ‘Danny Says’ because it was your typical ‘Phil the great build-up'— the master at work. And of course, ‘Do You Remember Rock ‘N’ Roll Radio?’ All the different and wonderful instruments that wove in and out of the song. And of course, ‘I’m Affected.’

“But to me, it all worked. The songs sounded like one and that's the way I feel all songs should sound. Not one thing should stand out louder than the other. ‘Chinese Rock,’ I liked the Heartbreakers’ version better because I liked the speed they played it. I thought ‘Rock ‘N’ Roll High School’ was definitely great. I also really like ‘Danny Says,’ which Joey wrote because I enjoy touring.”

I had a lengthy chat with Joey Ramone one night by the Gold Star Coca-Cola machine (which only stocked Tab) in the hallway. Joey, who shared the same May 19th birthday as Pete Townshend, was so stunned when I told him The Who mixed “I Can See For Miles” and produced “Call Me Lighting” at Gold Star, that he took off his glasses and shook his head in amazement. Joey and I had both seen the Who in 1967 on their first U.S. tour but on different coasts. Joey almost fainted when I told him that I had deejay Murray the K as a guest on my 1978 television show 50/50.