Hot and sour soup.

Annual bestie reunions.

An impromptu Elvis serenade.

The common thread?

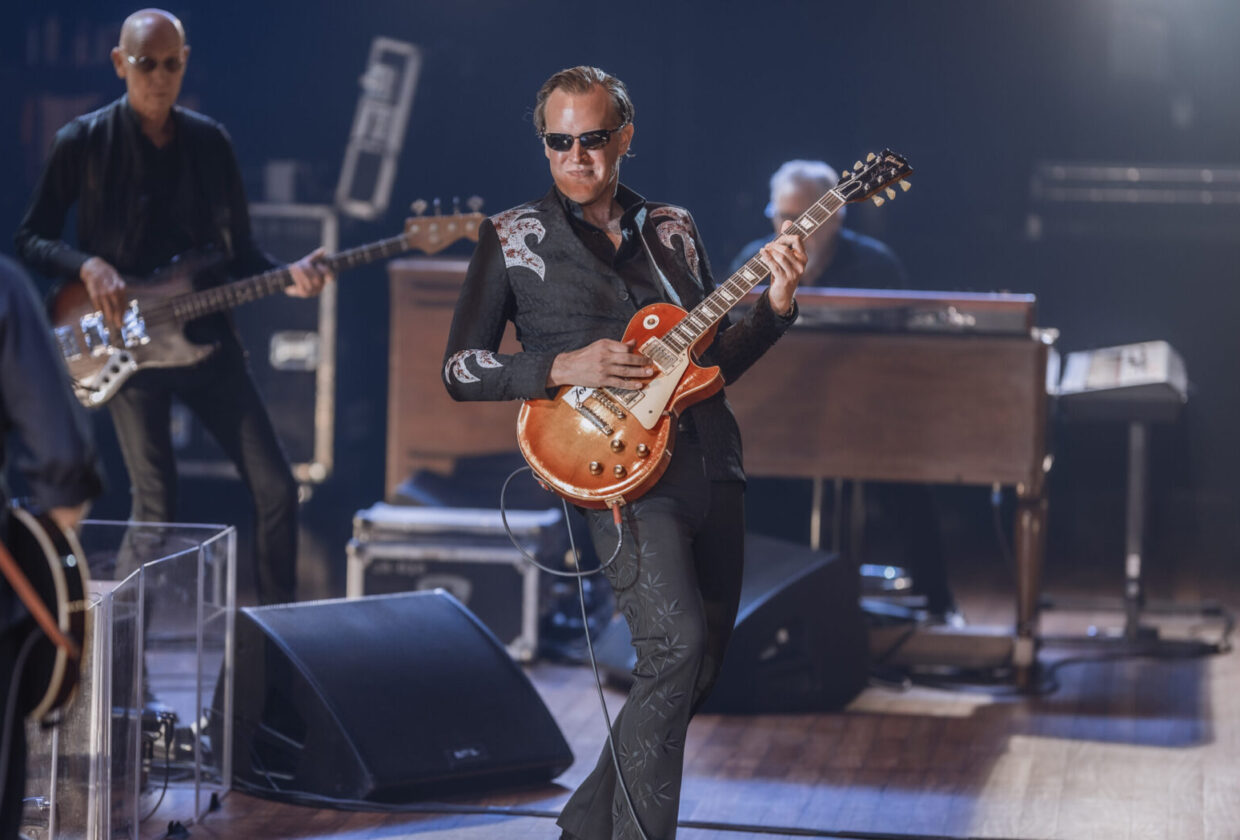

Joe Bonamassa.

As improbable as that combination seems, when it comes to the annual Keeping The Blues Alive Foundation cruise hosted by the guitar phenom, the thematic refrain revolves around expecting the unexpected. The same can be said for Joe’s career.

Picking up his first guitar at the age of 4, and playing chords by age 6, Bonamassa was sitting in with the best in the business by 12 (including B.B. King, Buddy Guy and John Lee Hooker). His objective at the time was to raise money for his first Fender amplifier (as a collector, he now owns over 400 amps and 400 guitars).

Having worked with various groups, and playing diverse genres to find himself artistically, Bonamassa’s music always returns to the blues and—without ever having a hit single (and not yet a household name, despite releasing 48 albums since 2000)—he holds the record for the most No. 1 albums on Billboard’s Blues Albums chart. With an upcoming 26-date U.S. Fall Tour, and the recent release of a special edition Fender amp, he joins Herbie Hancock for the L.A. Phil Jazz Series at the Hollywood Bowl in August.

Music Connection recently sat down aboard ship with the busy Bonamassa, for the following Q&A.

Music Connection: What is it about the blues, in particular, that pulls at your heartstrings?

Joe Bonamassa: It’s kind of where it starts and ends. We’ve been on so many different musical journeys over the years. When I write a song that’s a little out of my wheelhouse or genre, I always go, “Well, how do we make this bluesier?”—it defaults to that always. The thing about blues is the definition is so vast; everything fits under that giant umbrella that we’ve defined. There are people who think I have no blues in me, and that’s okay. My thing about the blues is we always have to be open-minded, because there’s so many different ways you can infuse it into music. It’s really kind of a blank slate to paint on.

MC: Absolutely. Let’s talk about the cruise and the KTBA Foundation. Was it something you always wanted to do?

JB: The Foundation was founded in 2011. Our fortunes had turned and we wanted to give back. It started humbly with $10,000, and we were giving away checks to schools for instruments and supplies. During the pandemic, we pivoted to raise money for musicians who got the rug ripped out from under them. Show simple proof that you had some dates canceled in 2020, and we had a $1,500 check for you. That’s when we started raising hundreds of thousands. There were government grants available with a lot of red tape you had to wade through. We didn’t want to do that.

I was in the airport around the GRAMMYs and saw a friend who had won. He came up to me to say that he had applied to the Fueling Musicians thing and wanted to thank me. That’s why I do all of this. It’s why we work so hard on this cruise: for those unseen benefits that happen. Here’s a kid in his 20s. $1,500 for him will move the needle. […] It’s the thing I’m most proud of in all of this—in my entire career—the fact that we were able to raise money. We had corporate sponsors and I put in 50 thousand of my own money. We had stream-a-thons, too, which was great. Artists would donate their music, filming in their pajamas like everybody else, and we put together sessions so people could donate. The first one raised $125,000, which was awesome. Of course, charity fatigue sets in, and now we’re back to the boat.

MC: So, musical impact aside, is this your legacy work?

JB: It is. Our business model is the legacy. There’s no real hit song per se. There are hits among the fans, but it’s not playing on classic radio every day. If you build it, they will come. If you do it the right way, and not try to skip steps, you’ll have a long-lasting career. It was brick and mortar: brick by brick, fan by fan, gig by gig.

MC: Backing up to 2015, when you did the first cruise, what has changed?

JB: We’ve perfected the fan experience in the sense that, on the first one, all of these things were kind of new. KISS was out, I think Kid Rock was doing one of these—it’s the same boat. There were less of them when we got involved. They convinced me the first year that it was in my best interest, the fans’ best interest, to line everybody up for four hours and meet every single person on the boat. It wasn’t fun for them. It wasn’t fun for me. Everybody got seasick, and it was four hours of just life. I’m not meeting you; I’m just standing there and I’m alive, you know? So, we stopped that. I’m trying to do more activities that reach the fans.

MC: A lot of people say they were addicted after their first cruise and they return every year. They say the experience and the interaction they get is really organic. They love that they can just speak to the human side of their idols.

JB: They’re really good about that. I can just go into the restaurants and say “Thanks for coming.”

MC: Now that most musicians are back working, the fundraising is focused back on school programs. How do schools hear about you?

JB: It’s a word-of-mouth thing. With schools, there is so much red tape now to even accept money from people. Our team does a really good job and, every once in a while, I’ll see someone from the Foundation pop up at a school with a check for them. The whole Foundation has taken on a life of its own. It’s good work. If you have a guitar program of 20 guitars and 19 of them are missing strings, rusted and unplayable, trying to get $200 worth of guitar strings would take forever through the bureaucracy. That $200 in guitar strings—by the time everyone voices their opinion—will probably cost $10,000 in sweat equity.

MC: So, was the label a natural evolution? Was that always part of it?

JB: We did Reese’s [Wynans] record in 2017. We were just going to put it on J&R Adventures and I had just started producing records (Reese got me into it). Josh [Smith] and I are in the studio with Joanna Connor, Joanne Shaw Taylor, Jimmy Hall and Larry McCray, Mike Zito, and Mark Broussard. For me, it’s all or nothing. When I get into something, I’ll do six a year.

MC: I’ve noticed that, a pattern of “to the wall”?

JB: It’s obsession. We decided to put a charitable spin on the thing. If you’re making blues records in 2023, you’re guaranteed to make a small fortune by starting with a large one because nobody’s buying music. But that’s not why we do this. With Larry McCray, we went up to Bay City, Michigan. The guy’s got no gigs, nothing going on, because his manager kind of kept him down for years. His manager died and he’s been on our list for years. How does this happen to a person who is so deserving, so freaking talented, so good? He’s a sweetheart, but he’s a badass. I said, “Larry, do you want to make a record?” and he said, “Yeah, I’ve just been waiting for somebody to give me an opportunity.”

It’s the same thing with Joanna Connor. I’m at Kingston Mines [blues club] in Chicago and said, “I’m tired of seeing you on YouTube. I’m tired of seeing Slash saying ‘This is my favorite new discovery’ on YouTube.” She’s been in the scene 35 years.

Same thing with Joanne Shaw Taylor, she’s been kind of skipped around. She was on Sony in the U.K. and was just never serviced the right way business-wise. Jimmy Hall sang with us down at the Ryman in 2020. He said, “Man, I’m going to be 70 years old and I still sing like a bird. Would you make a record?” I said “Yeah, let’s do it.”

MC: So, each artist was someone you worked with, or found along the way, and kept tabs on?

JB: Once we started this thing, people started knocking on the door. We’ve turned down more people than we’ve done, for the simple reason that the artist has to have a couple of things (like Eric Gales’ willingness to work with us), understanding that we’re going to do things differently than he or she has done in the past. I don’t care if you play with everybody. I need you to sing and I need songs—that moves the needle. If you can sing your ass off, and can deliver a good song, that immediately brings you up steps on the ladder. If it’s just another showcase of your prowess on the guitar or whatever, it’s just the same thing you’ve been doing. Some people just want the “Instagram moment.” It’s not worth their time or mine if we’re not going to really focus on moving them in their career. If you can make two consecutive great records, then you really get traction.

You don’t have to place first in American Idol. A lot of guitar players and people in the genre are reluctant singers. I was one of them until I met Kevin Shirley. Whether you like my voice or not, I’ve really applied myself and learned how to sing. The thing about all of that is when I’m in the room as a producer with Josh [Smith], there are people I’ve had to really sing the lines to and I’ll say, “Let me cut it—you sing to me.” We’ve done it that way and all of them have come out better vocalists. I had one singer tell me they normally get this stuff in two takes. I said, “Great. You give me two great takes, we’re good. You give me two shitty takes, we’re going to go 15 deep.” I know when it’s the right project when I want it more for them than they do.

MC: Your production is really powerful. Talk to me about your team…

JB: I mean, it takes a village.

MC: It does. But you’ve been with Kevin [Shirley] for a while and you’ve had your differences. What is it that keeps your relationship going?

JB: We disagree like family members. I gave him my word. I told him that once we got established and started doing these things, he would produce everything until I retire, and that’s it. That’s what keeps us going. Kevin has my number. He knows when I get lazy, he knows what I’m capable of, and he wants it more for me than I do.

MC: So that’s where you get it from?

JB: That’s where I got it from. I learned all my production techniques from him and Tom [Dowd]. Those were the two mentors. Tom produced my first solo album, and I watched him in the studio working with us. It was a collegiate-level course on life and music. I saw the same things in Kevin. Kevin is the best musician in the room, no matter who’s in the room. He may not know the numbers, but he hears it. He knows when it’s grooving and when it’s not, and he knows how to fix it. We have this great relationship [of] almost 20 years.

MC: For artists who follow your career, what advice might you give them?

JB: If you don’t bet on yourself consistently, how is anybody ever going to bet on you? Have that confidence and say, “I’m going to rent the room and I’m going to put my show on, regardless if I’m invited or not.” That’s been our mantra for 16 years—we’re going to bet on ourselves. A lot of artists are scared to do that because they want a guarantee, so their careers get truncated based on the whims of others. If you’re hot, everybody takes your phone call. The minute you sell one less ticket on a Tuesday night, one less record, or the next big thing comes in, the machine gets behind that. You got famous, [but] you’re like, “Wait a minute, what happened?” You got left behind. The music business slowly phased you out and you didn’t even know it because you were too busy trying to ingratiate yourself into a system that had no interest in your career. That’s a life lesson for a lot of people. So why not just bet on yourself? If you win, you’re going to win big. If you take a hit, okay, but at least you did it on your own terms. Learn how to market your gigs. It doesn’t cost much—everybody’s got a phone, an Instagram page.

MC: So where does that fearless mindset come from? I mean, the Royal Albert Hall show…?

JB: That was the bar mitzvah. It was a very strange kind of trajectory. We came in at the very end of pre-social media, so my first records were marketed in a very traditional way. People had heard of me from my first band, but it was just small pockets. We had initially very little success in the U.S. We would go into towns and we’d have to market this thing. We had 20 people, played our asses off and got 50, had 50 people to get 100… the word-of-mouth spread organically. When we hit Europe in 2002, there was instantly natural name recognition, meaning there were 200 people as a baseline, then 300. We’re in Europe and England with these crowds because I was playing British blues. I thought everybody played like Peter Green and Eric Clapton, [but] nobody was doing it—they were doing Stevie [Ray Vaughan] stuff. It’s a bunch of fedoras and Strat guys, so I come in with a Les Paul and this kind of throwback to the sixties British blues boom, and I cut right through. I had my own lane immediately. By 2009, we had worked the market to the point where we could do one show in the country—at Albert Hall. Mr. Clapton comes, we’re on PBS, and we’re off to the races. It was the watershed moment, but even on that PBS special, it wasn’t PBS doing it. That was us. We put all of our money in.

The DVD came out and did okay, and then a PBS affiliate in Albany asked for a one-hour edit. They were raising a record amount of money because, in 2010, I was by far the edgiest thing on PBS. It would have been Lawrence Welk, the Celtic Women, Reading Rainbow—and this guy. It was also a perfect storm because cable was changing. It was on big-time TV. We found out extremely fast the power of television. This is the break we’d been waiting for. We went from selling 750 tickets to 3,000, in one year. It was the thing we always hoped would happen, but we also kept ourselves in the game and kept positive, [knowing] eventually we were going to figure out something that’s gonna connect.

MC: So, was it always “Say yes and figure it out”?

JB: It was always [about] reinvesting in our business. We started in 2005 with four long shows. We bet all our proceeds from that tour on funding the two shows at the very end to see how it would go. We did Jacksonville, Florida, and we did Fort Wayne, Indiana, and the biggest offer I could get in Fort Wayne was $4,000. We did the same 1,200 people in the Embassy Theater that we were doing in the club, and we made $25,000. All through the years, we were just reinvesting in our business.

By 2010, we were promoting our own shows worldwide. I don’t have a booking agent. Promoters and agents will make you think putting on a concert is as complex as splitting the atom. It really isn’t. Our biggest obstacle in theaters and performing arts centers is Broadway. Hamilton will take two weeks, so the routing is very complicated sometimes. We book things far out. I think we have schedules up to summer of next year, with holds on venues.

MC: Blues is very traditional in its roots, and you strike me as very much a purist. Where do you think music is going? Do you see yourself moving with it, or standing firm?

JB: I think you’re going to start seeing people come out who had decent careers but who weren’t great songwriters all of a sudden having this metamorphosis. You’re going to see AI get involved, and there’s going to be people like myself who say, “I don’t care how shitty my song is, it was written by this human—and only this human.”

MC: So, you’re putting your flag in the ground?

JB: I’m sticking the flag in the ground. It’s a personal integrity issue for me. There are great songwriters in every generation, and they all have a certain personality, but AI is going to get really dicey. You’re going to see singer-songwriters who—and it’s not their fault if they decide to—check their integrity at the door. They’re just desperate to get a break. I understand that, but you’re going see people asking where did this song come from? “Oh, you know, I just locked myself in a cabin with my computer.”

I always say, “Man, I’m 46 this year. Whether I live to 85 or 100, I’m checking out right at the right time. This world’s going to get really crazy in the next 40 years.” What happens if your favorite album… [it] turns out some computer wrote it? Is it plagiarism? I don’t know. Who owns the IP?

The big data conspiracy theorist in me says, if I say, “Hey ChatGPT, go write me the best Joe Bonamassa song of all time,” and out comes “The Somber Ballad of Jonathan Henry II.” I write that song, put it out, it sells millions of records and wins all the GRAMMYs. Somebody who chooses to access the data goes, “Hey, I have your search engine and our algorithm wrote that for you.” Is that a Milli Vanilli situation where you have to give the GRAMMY back? We’re about to head into some very uncharted waters. The easiest thing to avoid that is to write your own damn song and just try to write the best songs you can. Not everybody is Bob Dylan.

MC: Looking back, what would you say is your best advice?

JB: Never compromise. If you know you’re good at something—it may not be the hippest thing—be the best damn accordion player in the world! If you’re rocking the sousaphone and have that drive and that thing, be the best damn sousaphone player in the world, or at least be the most enthusiastic—and be an entertainer. People lose sight of what business we’re in. I’m not a guitar player, a singer, or a songwriter. Those are tranches in the business. It doesn’t matter how good my guitar playing is, or how good the songs are if I just stand up there in my flannel shirt, stare at my shoes, and it’s boring?!

Contact Jon Bleicher at Prospect PR, jon@prospectpr.com