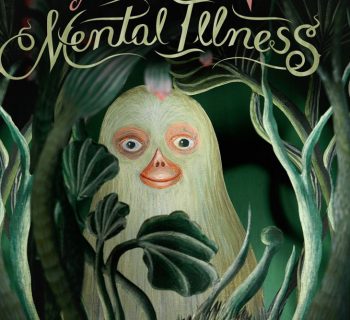

All set to kick off the second leg of his The Art Of Joy Tour at the end of May, Andy Grammer’s post-lockdown reemergence has unveiled an even deeper level of connection between the showman and his fans. Celebrating the release of his fifth album later this year, Grammer confesses that having to spend time alone and face his own insecurities has been challenging, but that it ultimately served as a catalyst to a new level of artistry.

With four albums, six EPs, dozens of popular singles, and multiple movie placements (including Captain Underpants: The First Epic Movie, Five Feet Apart and Bluey: The Movie) under his belt, Grammer’s steady rise has delivered multi-platinum hits including “Honey, I’m Good,” “Fresh Eyes,” and “Don’t Give Up On Me.” Between repeat appearances in the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade (which he describes as “an extrovert’s dream”) and participating in the 21st season of ABC’s Dancing With the Stars (which he says was the hardest and most vulnerable thing he’s ever done), Grammer brings a rare level of authenticity and humility to the stage, along with a passionate commitment to creating music that heals.

Music Connection: You’re such a unique artist because you have so much joy and life coming out of you—especially when there seem to be so many people “selling darkness” at the moment. This has always been your message, though, so what got you started in that way? How did you start on the path to really discovering that voice of positivity in your music, since it’s not that common?

Andy Grammer: It’s funny—I think that it’s kind of what works for me? I’d be lying if I said I didn’t try in different areas—to be like, “Man, am I supposed to be more sexy?! Is positivity cool?!” Hopefully as an artist you continually peel off layers and just get back to who you are. That seemed to resonate and it was always what I was best at: trying to uplift people. My purpose took me a little while, but I’m so grateful to be here—and that’s always the stuff that has resonated with everybody else. I get off on finding the things that could be perceived as cheesy and figuring out how to add depth and ground them. Everybody wants to feel joyful, but a lot of times the package is not something everyone can handle, so I know what I’m wading into. The Art of Joy Tour—I’m in on the joke and I know that it could be horrible, and then I’m like, “no—there’s truth in there”—and I get to work figuring out how.

MC: Absolutely. I’m glad you bring that up, because it really is a fine line between trying to sell joy, as opposed to showing up as joy, and it’s a big difference.

Grammer: It’s a huge, huge difference—and I think a lot of it is grounded in pain. I wrote “Keep Your Head Up”—the first song that went big—as a pick-me-up to myself. My mom had just died and I was street performing and no one cared. I was out on the street singing for 8 to 10 hours a day and when you sing “Keep Your Head Up” from that place, it’s sincere. I think that a lot of people can relate to that. It’s a lot of joy and optimism as a form of rebellion, as opposed to “just because.”

MC: You certainly seem to surround yourself with the best, and with people of like energy. Can you tell me a little bit about your management team?

Grammer: My manager, Ben Singer, has been with me for 12 years. He came and saw me as a street performer and the first thing we did was we bought me a better rug and a better tip jar, so he’s been with me from the jump. He’s like another member of the band, and all my music is in collaboration [with him]. I’ll write the songs and then me and him will go into the studio and kind of close it together. He’s got an incredible ear and an amazing heart, and he’s been the constant to this whole thing.

MC: It’s amazing to have that kind of longevity through various records, and to have that level of integrity at the core of your relationship is somewhat of a rarity.

Grammer: Yes, and to have someone else who doesn’t get very excited about music unless it’s doing good for people, you know? I don’t think all music has to be that way—there’s definitely room for all types of incredible music—it’s just that what gets me going personally are songs that are like little physical chiropractors: you feel a little bit more centered or something [after listening to them].

MC: You have talked about the upcoming album and how it was sort of a reinvention, and that there was this whole sort of rebirth that came about for you personally and professionally from the pandemic lockdown. What were your biggest takeaways or greatest gifts through this whole challenge?

Grammer: The greatest thing was to be forced to be alone, which I’m terrible at. I don’t like to be alone and never have, so I’ve very conveniently set up a life where I’m surrounded by thousands of people every day, and when it’s time to go to bed, there’s like 12 of my best friends who are all sleeping on a bus together. Dealing with the silence myself and realizing I was pretty unhappy—I started really getting into joy. My favorite definition of joy is “gladness not based on circumstance” and, If that’s the case, then you should still be happy when you’re alone in the silence. I realized that I had some real work to do there, and that’s what forced me into these self-love jams. If you had asked me before the pandemic, I thought I was really good at that, but when you took all the glitz and glamour away, I just had so much work to do. I write through whatever I’m going through, so songs like, “Damn, It Feels Good To Be Me,” and “Love Myself” just came from that. I’m never afraid to write about anything, because I know that if it’s embarrassing to me to write it, then I’m probably on to something pretty good. Whatever you’re dealing with, if you’re really really dealing with it, it’s probably fairly universal.

MC: I heard the new album is the culmination of a two-week lockdown with your favorite writers?

Grammer: Yeah, there’s a lot of good stuff that came from that—it was a lifeline to me. I was freaking out not being able to go anywhere, so we tested everybody and we went in for two weeks with Jake Torrey, who co-wrote “Don’t Give Up On Me”; Nolan Sipe, who co-wrote “Honey, I’m Good”; and my frequent collaborator, John Levine—who is just amazing and has been on all my albums. It was really cool to go in and not do it in the L.A. writing way where you all get there at eleven, talk for two hours, write for three hours, and then it’s time to go. It was like sleepover camp, and we kept going at them [the songs]. We would get some food and talk about it—a real intensive occurred that I would love to do again. I made omelets for everybody every morning and we played MarioKart every night—it was great.

MC: It’s great that you have such tenure, have worked frequently together over the years, and that you’re together again for the latest record as well.

Grammer: Experience is really important. To get something that actually resonates with everyone. Nobody knows that, that’s a lucky thing. But I do think as you go along—the more and more songs you write—there is a bullseye, and you start hitting the board every time. On my first album, I wrote a hundred songs and some of them didn’t even hit the board or the wall—not even close. Now it’s usually fairly close, and then magic happens every once awhile, especially when you find people who really complement what you have (and you find those people along the way).

MC: You touched on joy and positivity being really just who you are, and how you choose to show up in the world, but—given everything that’s going on—what do you use as your grounding point? What keeps you humble and stable and holds you in that space, or what tools do you use to keep you there?

Grammer: Well, one is the Baha’i faith, a religion based on the unity of religions—there is just a lot of really incredible writing there that I was raised in and I do my best to pray every day and stay grounded in that way. And then, you know, it’s a lot of self-work. The therapy during the pandemic—I’m going for it on the invisible work. There’s lots of invisible bricks to be carried that I’m finally coming around to that I just couldn’t shake off when I was stuck in quarantine, so that’s not super fun, but it’s important if you want to have a brain that’s happy.

MC: You’ve been through some stuff, losing your mom really early. Do you think that those experiences and a lot of the ups and downs, through busking and the rest of it, do you think that has change your outlook and do you think that’s part of what keeps you humble and showing up in the way that you do?

Grammer: Yeah, sure. I also think it just makes it more palatable. You don’t want to hear uplifting music from somebody who hasn’t been through shit. I don’t want to hear “Keep Your Head Up” from somebody who’s never been through it. I don’t want to hear “Don’t Give Up On Me” from someone who hasn’t really felt suffering.

MC: Let’s talk about “Joy,” the lead track to the new album. What came first, the lyrics or the music? And what is it about this song (apart from the obvious), where did it come?

Grammer: I don’t know whether there’s a word that talks about being happy in a way that has such a grounded depth to it? Happiness is floaty; you can be happy one moment, and then not happy. Joy feels like you’ve done work, or you’ve been through something to get there. It started out as a concept of how cool it would be to play off of past relationships and be like, “I’ve dated all these different things”—sorrow, grief, jealousy—and write it in that form and then land on, “I finally found joy.” I really loved that idea and I brought in Michael Pollack, he’s an on-fire writer right now, and I think he got it. I imagine when it comes up in your playlist and you see a song called “Joy”—like, okay, how’re you going to do this?! It’s not easy to pull off joy. It’s really hard to say it in a genuine, authentic way. If you can do it, it makes people so happy, because we all need joy and we need to relate to each other and the things that talk about our higher nature and fill up our soul and our heart. It’s just that so much of that is so freaking sweet that it’s hard to get it. I had a kind of whisper that I was supposed to go in this direction—that word “joy.” Horns felt like the next step.

Grammer: I don’t know whether there’s a word that talks about being happy in a way that has such a grounded depth to it? Happiness is floaty; you can be happy one moment, and then not happy. Joy feels like you’ve done work, or you’ve been through something to get there. It started out as a concept of how cool it would be to play off of past relationships and be like, “I’ve dated all these different things”—sorrow, grief, jealousy—and write it in that form and then land on, “I finally found joy.” I really loved that idea and I brought in Michael Pollack, he’s an on-fire writer right now, and I think he got it. I imagine when it comes up in your playlist and you see a song called “Joy”—like, okay, how’re you going to do this?! It’s not easy to pull off joy. It’s really hard to say it in a genuine, authentic way. If you can do it, it makes people so happy, because we all need joy and we need to relate to each other and the things that talk about our higher nature and fill up our soul and our heart. It’s just that so much of that is so freaking sweet that it’s hard to get it. I had a kind of whisper that I was supposed to go in this direction—that word “joy.” Horns felt like the next step.

MC: Speaking of which, where did you find the fantastic all-female horn section?!

Grammer: I knew that I needed horns and was switching out my backup singers—two of them were female and I did not want to have an all-male band. You need all the different things that women bring to the stage, the female point of view. It was really tough to do, because my backup singers were incredible, but I could feel the call that I had to go with horns and the only way I was going to do it was if they were female—and these three ladies crush!

MC: They’re badass for sure. You’ve spoken recently about conversations you’ve had with female members of your tour and hearing about the things that they deal with. Has anything changed since those first conversations?

Grammer: For sure. Just being really aware that you don’t know things and asking as much as possible; really open communication, making sure that everybody feels heard. Especially as a white guy, my viewpoint is not necessarily going to cover the whole spectrum of what this is, so I need to be really open to everybody else’s input. It’s from a from a place of ‘oh man, I have straight up blind spots,’ so I need all the information to make something great. I don’t want to be in any sort of an institution that doesn’t have a huge diversity of men and women—it’s a terrible idea—it’s a totally different energy.

MC: Your recent show in Anaheim was somewhat of a homecoming and wasn’t far from where you started busking and where you were first discovered. How was that for you, especially in light of the recent reinvention?

Grammer: It was so sweet to be around people. It’s lovely to be seen. The closer you get to being authentic when you do your art, the more often you are seen—and to have all your close family and friends, as well as a lot of people who have known me as a street performer and have come to a lot of my first gigs in L.A.—it’s just really sweet to share that with your hometown.

MC: I have to add—when I was waiting to get into your show, there was a family behind me with two little girls about the same age as your daughters, and it was their first concert. They were huge fans of yours and it was interesting that they were so young.

Grammer: What’s so sweet is that when you’re singing about the soul, which is kind of what I’m doing, there’s no age for that, so the audience is literally six-year-olds to 70-year-olds and everybody in between. No one is excluded. I’m not just singing about the first time you fell in love, I’m singing about the soul, so everybody can get down with that. It’s just so joyful to see such a wide array, it’s like a party that everyone’s invited to.

MC: You actually wrote an article for Music Connection—shortly after you were signed to S-Curve—about how to be a successful street musician, and you had some great advice! I was curious if you had anything to add to the advice you gave back then?

Grammer: It’s amazing—I was just going a hundred percent at whatever was in front of me at that moment. Right now, there are a lot of other things in my vision but at that time that was all that there was—and I just went a hundred percent at it.

MC: So much of that is echoed in how you show up now, and it’s clearly a formula that works.

Grammer: It’s just the idea of “How do you give more than you’re taking?”—which is hard to do on the street, but I can be done. The biggest lesson that I took from the street was when I first moved to L.A. and I’m playing music—strangers or anybody that comes to your crappy little gig at a bar—they’re giving you their attention, they’re giving it to you, because you’re not good. Over four years of street performing, there was a lot of tweaking and writing songs and new things to get it to where that shift actually happens, to where I’m giving it to you. Once that happens, everybody is psyched because they’re getting something from you. What an incredible job to do, to fill people up?! On the whole tour, I would just get off stage and be like, “I can’t believe I get to do this?!” I always equate it to…there are a lot of astronauts, and not that many get to go to the moon—but every night I get to go the moon.

MC: You introduced two new songs at your show: “New Money” and “Saved My Life” and you had the crowd singing the chorus on those. Where does that come from? I know it’s a bit of a trademark, but is that a throwback to your busking days and always wanting to engage your crowd?

Grammer: Yeah. I think it’s also when you’re playing something brand-new that no one’s ever heard. So often now at shows, people know their part. They know all the words and it’s just a dream, it’s amazing. You want to kind of keep that going. On “New Money,” we recorded a lot of huge crowds singing that and we put it on the record.

MC: That’s another way that you really create that investment by having everyone in the room, and your fans as a whole, be part of something. That’s so important. Would you say that technology has changed that whole experience?

Grammer: I think technology has made it so that you can have niches that are bigger than they’ve ever been. It allows you to be riskier, more trickled-down on who you are as a person and as an artist, and still have a way to get to everybody, which is really liberating as an artist. It allows me to more directly communicate. There are all these playlists that didn’t exist when I was just starting. My type of music has a way of getting to the people who want to hear it, as opposed to just a huge blast to everyone. The blast is smaller than it’s ever been and it’s even cooler to go to all these little side roads to get exactly where your fans are.

Contact Amanda Brophy,

amanda@theoriel.co

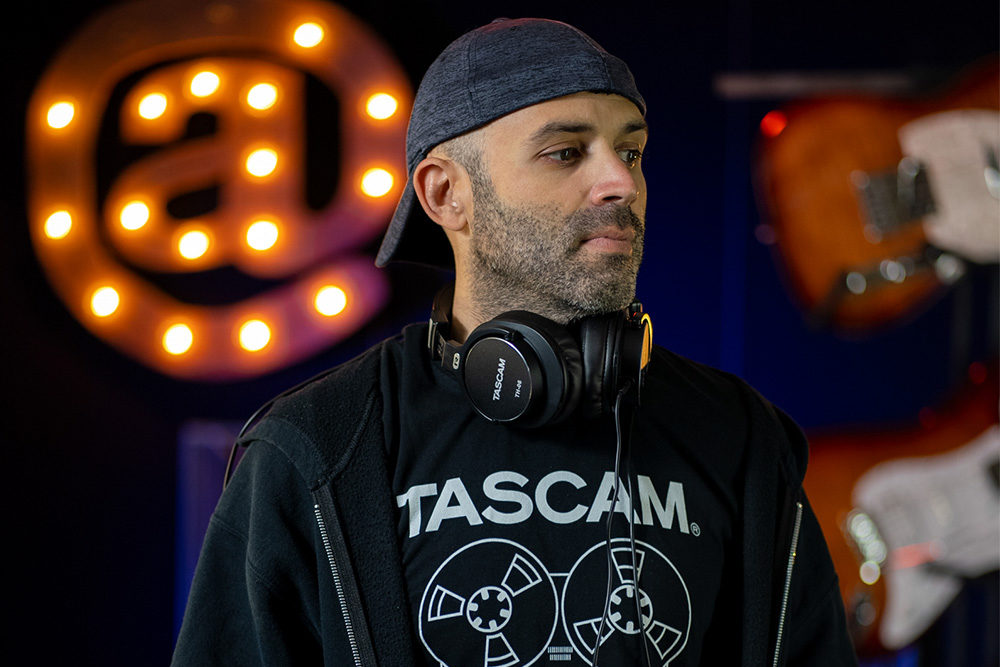

Photos by Alex Harper

QUICK FACTS

•Grammer’s father is singer-songwriter Robert Crane “Red” Grammer (formerly of renowned folk trio The Limeliters, Through Children’s Eyes), who is best known for his children’s songs (“Can You Sound Just Like Me?,” “Down the Do Re Mi,” “Hello World,” etc.), which he first began writing for his sons.

•Born in Los Angeles, Grammer was raised and schooled in Chester, NY, but now lives back in Los Angeles with his wife and two daughters.

•First starting in music by playing the trumpet, then guitar and piano as a young child, Grammer began writing his own songs at age 15.

•The nightly bath time ritual with the Grammer kids features music by jazz great, Louis Prima, including “Pennies from Heaven.”

•Debut video “Keep Your Head Up” featured actor Rainn Wilson and was an iTunes video of the week in 2010, winning MTV’s “O Music Awards” for most innovative video on April 25, 2011.

•Grammer and his mother Kathy were big fans of Paul Simon’s Graceland album, and 2019’s “She’d Say” (recorded with Ladysmith Black Mambazo) was written after a conversation with a medium, who channeled a message to Grammer from his late mother about writing the song.