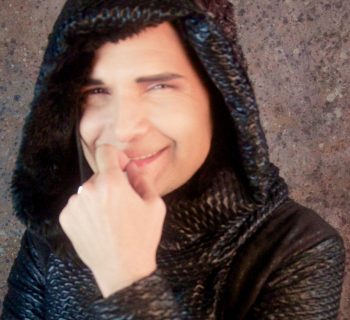

Since the release of his blockbuster solo record, Frampton Comes Alive, in 1976, and his indelible hit singles “Show Me the Way,” “Baby I Love Your Way” and “Do You Feel Like We Do,” Peter Frampton has forged a multifaceted music career, working with artists including George Harrison, Ringo Starr, Jerry Lee Lewis, Harry Nilsson, and childhood friend David Bowie, while also releasing solo recordings and steadily touring. It’s a wide-ranging career that was duly recognized in January at the NAMM TEC Awards in Anaheim, CA, where the virtuoso musician was given its prestigious Les Paul Innovation Award.

Frampton’s dazzling performance that night made it all the more shocking when, two months later, he announced he has been diagnosed with a rare muscular disorder, Inclusion Body Myositis (IBM). Undaunted, however, Frampton soon hatched plans to record and release a new record, All Blues, by Peter Frampton Band, and undertake a slate of stadium dates, dubbed “Peter Frampton Finale––The Farewell Tour.”

Frampton, 69, has commented that the diagnosis is not life-shortening, but is a degenerative condition that leads to muscle weakness and possibly atrophy. He plans to give his fans proper performances while he is still comfortable to perform at his optimum. Jason Bonham’s Led Zeppelin Evening will open the dates, with many special guests expected to appear throughout the tour. “Peter Frampton Finale—The Farewell Tour ” launched on June 18 and is scheduled to run through October, with about 40 scheduled dates across the US.

With his longtime touring band (Adam Lester, guitar and vocals; Rob Arthur, keyboards, guitar, vocals; Dan Wojciechowski, drums) playing on the album, Frampton selected his favorite blues songs to cover, including “I Just Want to Make Love to You,” “The Thrill is Gone,” and “I’m a King Bee.” He also had company in the studio from friends including Kim Wilson and Steve Morse. The album is co-produced by Frampton and Chuck Ainley for release on Universal’s UMe.

To promote the release of All Blues in June, SiriusXM satellite radio’s Deep Tracks (channel 27) launched a six-week series in May, The Peter Frampton Show, with Frampton hosting, and a special program in June, Peter Frampton’s All Blues Show, on the B.B. King’s Bluesville station (channel 74) on which Frampton plays and discusses the new album track-by-track.

Music Connection interviewed Frampton as he put the finishing touches on the album at his studio in Nashville.

Music Connection: How is the recording process going?

Peter Frampton: Since October of last year, I’ve done more than 40 tracks. It’s the most recording I’ve done in my life in that amount of time.

MC: You are such an enthusiastic live performer. How do you maintain that level of enthusiasm and love of performing after all this time?

Frampton: For me, when I play live, onstage I’m in a world where I’m not thinking about anything else, and I am off creating, in the moment. I’ve always been that way. I’m on stage and I play the first note and I smile. It’s such a passion for me; I can’t control my smiling. I was born to be on the stage.

MC: In your early career, with The Herd and Humble Pie, you were a band member, and later, you were an in-demand session guitar player. What was it like to transition to being a solo artist?

MC: In your early career, with The Herd and Humble Pie, you were a band member, and later, you were an in-demand session guitar player. What was it like to transition to being a solo artist?

Frampton: I’ve been in bands, school bands and then very successful bands, The Herd and Humble Pie. Humble Pie being worldwide, and there was something that I just felt at that particular time when we were mixing [the 1971 album] Rockin’ the Fillmore. I felt that this is going to be the breakthrough for Humble Pie, and I don’t want to be here. I want to go and do my own thing, which was very brave for a 21-year-old. So before the album was released, I let everyone know my intentions, and everyone was not thrilled. And then, of course, three months later when the thing comes out, it’s leaping up the charts on both sides of the Atlantic.

And I really did think that I had been very lucky, made the right decisions so far, but I’ve messed up now. Yet I didn’t want to go back; these are the cards I’ve been dealt. I felt freer being in charge of my own destiny as opposed to being a part of a band. I suppose that’s what I needed at that particular time, so I found that period incredibly creative, as I did with the period with Humble Pie as well, but I was enjoying doing everything that I had written or doing covers and being able to choose the style of music and what I wanted on my first record, Wind of Change.

MC: How do you prepare for performing live versus recording?

Frampton: I think there shouldn’t be too much difference between the two. Except there’s an audience for one of them! We have gone in the recording industry with technology leading us by the hand from tape to digital to streaming. The way we used to record, we didn’t have that much technology, that many tracks. The band had to be good enough to play live all at once in the studio and that is not the way most people, including myself, record now, laying down the keyboards, the guitar, building a track, and many, many great records have been made that way. But there aren’t really any rules as far as audio goes now.

And I have just made the total realization: We did 71 shows last summer, me and my band, and we took nine days off, and went straight into my studio in Nashville for 10 days and came out with 33 tracks. It just blew me away. These are blues covers, but we put our own spin on them, our own arrangements. Playing live with the band, singing live in the studio is as close to playing live as you’re going to get to playing live on a stage, except there’s no audience. We rediscovered how to enjoy recording to the max.

When I walk in the control room and hear it played back, my band are incredible. I’m the luckiest guy in the world. The musicianship––we are like five brothers. We get along and we play so well together. The crux of the band have been together over eight years. We are using a new bass player. I might have gone from being in a band to being a solo guy, but “you can take the guy out of the band and you can’t take the band out of the guy!”

When I walk in the control room and hear it played back, my band are incredible. I’m the luckiest guy in the world. The musicianship––we are like five brothers. We get along and we play so well together. The crux of the band have been together over eight years. We are using a new bass player. I might have gone from being in a band to being a solo guy, but “you can take the guy out of the band and you can’t take the band out of the guy!”

I love my band, this new project––Peter Frampton Band––it’s a different project. I think when everybody hears it, they will find that it’s very organic; it’s very in the moment. Are there little tiny mistakes here and there? Uh-huh. But it’s rock & roll. It’s blues, it’s live, and it’s the real thing. There’s nothing fake about it. We just went in there, started playing, came out, and there it was.

MC: You are known for your iconic Gibson Les Paul, which you still prefer. It was thought lost forever after a cargo plane crash, yet it was recovered many years later. What else is so special about that guitar?

Frampton: When I was playing with Humble Pie in 1970 I was playing a 1962 Gibson SG and I loved it! But halfway through the tour I decided I’d like to change and use a hollowbody guitar, a Gibson 335. You never had more than one guitar in those days, so I swapped it and paid extra cash for this beautiful 335. Unfortunately I got onstage with Humble Pie, and we played so loud, and it being a hollow bodied guitar, the technology to that is that it will feed back and howl when you turn it up. So all of my solos with that guitar with Humble Pie were like [makes the sound of a sad cat yowling] it wasn’t thrilling, put it that way.

So we’re playing San Francisco, I think it was Winterland or the Fillmore West, and this friend of mine, Mark Mariana, who collected guitars was there, and after the show he says, “I couldn’t help noticing you’re having a little problem there.” I said I never should have sold that SG. He said, “Well, I’ve got this Les Paul that I just got back from being refinished by Gibson, would you like to try it tomorrow?” So I told him that I’m not big on Les Pauls, but you know what, anything at this point. So he comes around to breakfast the next day and holds it up in the coffee shop and it was so gorgeous! Just this beautiful three pick-up Les Paul.

MC: So it already had the three pick-ups?

Frampton: Yes, it did. It wasn’t originally a three pick-up guitar. It’s what’s called a Black Beauty. It’s a 1954 Black Beauty, the “fretless wonder” because they had such thin frets on them. He had asked Gibson to do that, so it’s kind of a Frankenstein Les Paul. So I played this guitar for both sets the next night and I don’t think my feet touched the ground the whole night!

It was just a completely new experience for me, apart from it feeling like the guitar had been made for me. He had done special sanding on the back of the neck, on the body; he had it very customized. It fit my hand like a glove and it sounded amazing so that’s why it meant so much to me. It became the guitar I used. It was on Rockin’ the Fillmore, John Entwistle’s Whistle Rymes, Harry Nilsson’s Son of Shmilsson, all the sessions I did between ‘70 and ‘75, something like that. As a session guy, as I was starting my solo career.

He didn’t sell it to me, he gave it to me. So I have given him many guitars in return, and tickets to fly places, whatever it takes. When we lost the guitar in a plane crash, I called Mark and said, “well you found this one for me, can you find me another one?” He looked, but we didn’t find anything. I couldn’t play anything else the same. I found it very difficult to play anything else, even other Les Pauls, because they were so different.

MC: Of all of the artists and guitar players you have worked with, what lessons have you learned and what experiences were notable?

Frampton: As far as a guitar player, I’ve worked closely with Steve Morse, from Dixie Dregs and Deep Purple, who is the guitarists’ guitarist, and he is a dear friend. He’s playing on one of the tracks on my upcoming release. Years and years ago he called me up and said, “Can we write a song together?” And we wrote a song, I went down there to his studio and sort of had practice sessions and he taught me all these exercises that he uses to practice and warm up, I think I learned a lot from him on a one-to- one basis. I’ve learned stuff from watching other players and listening to other players but that was one-on-one.

Working with David Bowie, not so much the guitar playing obviously, but I learned from working with him a lot about how to do a tour. Of course l’ve listened to a lot of guitar players and learned a lot from a lot of guitar players, but Steve Morse, that was one-on-one. And I’m still learning…from Django Reinhardt to Jimi Hendrix, and everybody in between.

Working with David Bowie, not so much the guitar playing obviously, but I learned from working with him a lot about how to do a tour. Of course l’ve listened to a lot of guitar players and learned a lot from a lot of guitar players, but Steve Morse, that was one-on-one. And I’m still learning…from Django Reinhardt to Jimi Hendrix, and everybody in between.

MC: You have often cited Django Reinhardt as one of your initial influences. How did you start listening to him?

Frampton: My mother and father would dance to the Quintette du Hot Club de France, which was the band, Django and Stephane Grappelli, and his brothers, that was the band. That was my parents’ version of disco. For a dance and a cocktail, you know. When we got our first record player, Dad came home with a record for me, The Shadows with Hank Marvin on lead guitar, and a Django Reinhardt record, so I would put on a Shadows record and Dad would wait for me to be done. And then I’d be going up the stairs, and I couldn’t get up the stairs fast enough before the Django Reinhardt jazz stuff was on. Oh my God! What is that? So I hated it. And one day I stopped half way up the stairs and listened and realized, oh my God, this guy’s good! I walked back down and sat in and the next time he put the record on after The Shadows I stayed.

After that, I would play each one equally, for the rest of my life. I still have just about everything Django and Marvin and The Shadows have done. Even though they are vastly different styles of music, they are still the building blocks that I listen to in order to find my own guitar style. Amongst many, many others, from Wes Montgomery, B.B. King, Buddy Guy, Eric Clapton. You name them I’ve listened to them. But I think the first two inspirational players for me were Hank Marvin and Django Reinhardt. At the same time.

MC: Coming from that background, what did you think of Chuck Berry?

Frampton: Oh yes, he invented this style, basically like a boogie-woogie piano on the bottom of the guitar and then he came up with these sort of brass parts, almost like he was playing brass parts on the guitar. It was the first interesting unique style of rhythm and lead that came out of early blues. Or sort of mid-blues. Jimmy Reed…there are so many other players.

MC: You’ve been very candid about discussing your diagnosis, beginning with an exclusive interview with correspondent Anthony Mason on CBS This Morning: Saturday back in March. You’ve also created a foundation with Johns Hopkins University, where you are being treated, The Peter Frampton Myositis Research Fund at Johns Hopkins. Is there anything you’d like to add to what you’ve already stated?

Frampton: As I said in that interview, I’ve known about the diagnosis for four years. I’ve probably had it for eight. I knew, when it was time, I wanted Anthony Mason to tell the story. I had been preparing for this for four years. I don’t feel I have to expand on it.

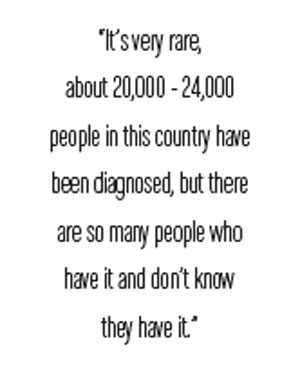

It’s very rare, about 20,000 to 24,000 people in this country have been diagnosed, but there are so many people who have it and don’t know they have it. When you first notice weakness in your legs, you think you’re getting old. I was in my mid-50s. And then I felt weakness in my arms. It’s very slow, very difficult to diagnose; sometimes it takes three or four diagnoses before they get it right. I encourage people to visit hopkins.myositis.org.

Contact cami.opere@sacksco.com