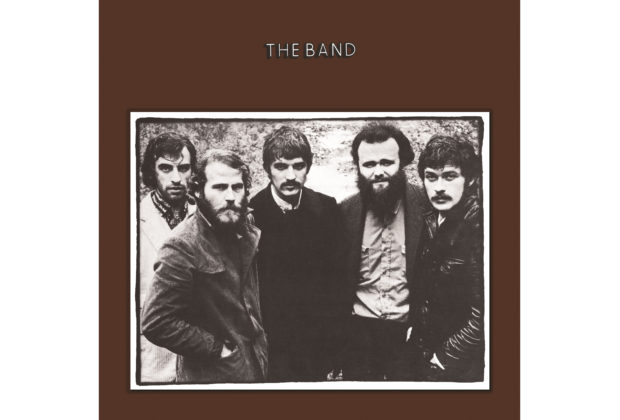

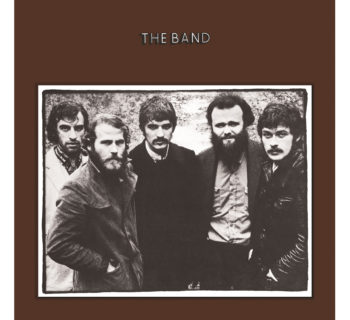

When The Band’s seminal eponymous second album was released 50 years ago on Sept. 22, 1969, not much more was known about the reclusive group than when they released their landmark debut, Music From Big Pink to widespread critical praise and bewilderment, just the year before. The band, made up of four Canadians and one American, was still shrouded in mystery, allowing for listeners and the music press to let their imaginations run wild about who these men were and what this music was that sounded unlike anything else happening at the close of the psychedelic ‘60s.

Dressed like 19th-century fire-and-brimstone preachers and singing rustic, sepia-toned songs about America and the Deep South, The Band—Garth Hudson (keyboards, piano, horn), Levon Helm (drums, vocals, mandolin), Richard Manuel (keyboards, vocals, drums), Rick Danko (bass, vocals, fiddle) and Robbie Robertson (guitar, piano, vocals)—was an enigma, unlike any group that came before or after. And their self-titled “Brown Album,” as it would lovingly be called, cemented their status as one of the most exciting and revolutionary bands in years, on the strength of now-classic songs like “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down,” “Up On Cripple Creek” and “Rag Mama Rag."

On Nov. 15, Capitol/UMe celebrated The Band’s pioneering self-titled album with a suite of newly remixed and expanded 50th Anniversary Edition packages including a Super Deluxe 2CD/Blu-ray/2LP/7-inch vinyl boxed set with a hardbound book; 2 CD, digital, 180-gram 2LP black vinyl, and limited edition 180-gram 2LP “tiger’s eye” color vinyl packages.

All the Anniversary Edition releases were overseen by Robertson and feature a new stereo mix by Bob Clearmountain from the original multi-track masters, similar to the acclaimed 50th-anniversary collections of last year’s Music From Big Pink releases. The 50th Anniversary Edition’s CD, digital, and box set configurations also include 13 outtakes, featuring six previously unreleased outtakes and alternate recordings from The Band sessions, as well as The Band’s legendary Woodstock performance, which has never been officially released.

Exclusively for the box set, Clearmountain has also created a new 5.1 surround mix for the album and bonus tracks, presented on Blu-ray with the new stereo, both in high-resolution audio (96kHz/24bit). All the new audio mixes have been mastered by Bob Ludwig at Gateway Mastering. The box set also includes an exclusive reproduction of The Band’s 1969 7-inch vinyl single for “Rag Mama Rag” / “The Unfaithful Servant” in their new stereo mixes and a hardbound book with an extensive, illuminating new essay by author and music critic Anthony DeCurtis and classic photos by Elliott Landy which have had an inimitable influence on rock and roll. For the album’s new vinyl editions, Chris Bellman cut the vinyl lacquers for the album’s new stereo mix at 45 rpm at Bernie Grundman Mastering, expanding the album’s vinyl footprint from one LP to two.

Clearmountain and Robertson’s approach to remixing the beloved album was done with the utmost care and respect for the music and what The Band represents. “The idea was to take you deeper inside the music, but this album is homemade,” Robertson says in the liner notes. “You can’t touch up a painting. It has nothing to do with what you get when you go into a recording studio.” When he expressed his concerns to Clearmountain, the renowned engineer and producer reassured him:

“We’re just trying to overcome the original technological limitations in order to bring you closer into the room,” cited Robertson in the UMe press release. “I’m going to do everything in my power not to get in the way of this music at all.” The result is a new mix that allows listeners to hear these classic songs in stunning, and oftentimes startling, clarity, packing more of a sonic and emotional punch than ever before. The included early and alternate versions offer fans the ability to hear the evolution of these tracks or as Robertson says, “That’s us trying to teach ourselves how to play these songs.”

Released in 1968, The Band’s game-changing debut album, Music from Big Pink, seemed to spring from nowhere and everywhere. Drawing from the American roots music panoply of country, blues, R&B, gospel, soul, rockabilly, the honking tenor sax tradition, hymns, funeral dirges, brass band music, folk, and rock & roll, The Band forged a timeless new style that forever changed the course of popular music.

Shortly after the release of Music From Big Pink, the members of The Band relocated to Los Angeles to record their follow up album. Searching for the same clubhouse vibe they had at Big Pink, they eschewed a traditional studio and moved into a house in the Hollywood Hills that had previously been owned by Sammy Davis, Jr. The place had enough bedrooms that the group could reside there with their families and a pool house where they set up the studio.

While Capitol Records was dumbfounded the guys didn’t want to record in one of their state-of-the-art studios down the street, they ultimately relented and paid for the shipment of their equipment across the country. Recording here was not without its obstacles as getting an upright piano up to the house proved trying and since they were in a residential neighborhood, the pool house needed to be soundproofed from the outside, which was quite a sight.

Following dinner together with their families in the main house, The Band, joined by co-producer John Simon who helped shape their sound, as on their debut, would shuffle off to their makeshift studio to write and record their masterpiece, working through the night and stopping around dawn. Listening to these dusty, rural songs, it’s hard to believe they weren’t written in the Appalachian Mountains but instead perched up in the hills overlooking Los Angeles’ sprawling, smoggy metropolis.

In 1976 I attended The Last Waltz, the final show by The Band at the Winterland venue in San Francisco.

During 1975, 1978 and 2017 I interviewed members of The Band.

In November 2018, Sterling/Barnes and Noble published The Story of The Band From Big Pink to The Last Waltz, a book I wrote with my brother Kenneth.

amazon.com › Story-Band-Pink-Last-Waltz

pastemagazine.com › 10 of the year’s best music books

In my 1975 interview with Robbie Robertson for Crawdaddy magazine, I asked Robbie about the double keyboard combination of piano and organ. I wondered if guitarist Robbie ever felt suffocated by this format.

“No. I play as much as I want to play. No one is telling me, ‘Listen, you’re playing too much.’ That’s my own decision. That’s how much I prefer to do. When I hear other people play a lot more than required I find it really drivel and there’s nothing in this fuckin’ wide world that’s going to do anything for the song; I don’t care. I like a good guitar part where it adds something, has a nice place and is a nice solo. Not too much, not too little. But I think as time goes on it just takes different proportions, and too much is unnecessary.”

Robertson’s guitar theory seems to simply extend his basic life philosophy of unhurried discipline.

Or, as Bob Dylan said when he called to talk about Robbie for the magazine: “Listen to his guitar playing. That’s all you have to know about him.”

In 2017 I interviewed Robertson for Record Collector News about The Band.

During 2016, Columbia Records and Legacy Recordings issued Bob Dylan: The 1966 Live Recordings, a 36 CD box of 1966 concert tours of the US, UK, Europe and Australia.

When I talked to Robbie in 1976 about The Band reuniting with Dylan on the 1974 tour he remarked, “At least this past time we weren’t booed,” referring to confusing nights on the Dylan/Hawks 1966 tour.

I confessed to Robbie in our 2017 chat that I still have a hard time comprehending Dylan and the group being booed in 1966. What I remember about the three 1974 shows I saw, everyone was totally digging the blend on stage.

“There was a thing that happened between Bob and the Band on stage that when we played together that we would just go into a certain gear automatically. It was like instinctual, like you smelled something in the air, you know, and it made you hungry. (laughs). It was that instinctual. And the way we played music together was very much that way. And whether, we were playing in 1966, or 1976, or when we did the tour together in 1974, we would go to a certain place where we just pulled the trigger. It was like ‘just burn down the doors ‘cause we’re coming through.’ And it was a whole other place that we played when we weren’t playing with him. So it was like putting a flame and oil together, or something. I don’t know.

“When we did the Dylan and Band tour in ’74, where we went and did a lot of the same things we did back in ’66, and the peoples’ response was ‘this is the shit and I knew it all along.’ It was like you weren’t really there all along. It’s interesting and it’s one of the things I talked about in my keynote speech that I made [last decade] at the SXSW conference.

“It’s really a very interesting experiment to see, or go from something that people were so adamantly against this music, and that we didn’t change nothing, and the world revolved, and everybody came around and said ‘this is brilliant.’ That was very interesting to see everything else change around you.

“Well, we didn’t change. [laughs]. I don’t know that this has ever happened to anybody else. And it is a phenomenon. And that’s why I feel bold enough to refer to it as a musical revolution, because the world came around. We didn’t. We didn’t do anything that much different. [laughs]. We just went out there and hit it between the eyes. And now people have a completely different reaction to it. And I thought ‘that’s kind of incredible that the world actually came to this place,” you know. And I don’t know who else has been through that."

Robertson and I reminisced about The Basement Tapes and Music From Big Pink.

“When we hooked up with Bob Dylan it was made clear to Bob and to Albert (Grossman), ‘this is a whistle-stop for us.’ We are on our own path. We’ll do this in the meantime but we’re going to do our own thing. We’re not here. We’re here to do this. Right?

“After we did the thing with Bob and he wanted to do more. But he had this accident and so then, and I say this in the book, Albert had no idea what we were or what we could do. No idea. He liked us. He thought it was really interesting what we did with Bob. But he said ‘I think I can get you a deal for doing an album of instrumentals of Bob Dylan songs.’ So I said, ‘All right. Let me talk to the guys about that.’ (laughs). And I thought, ‘Albert has no idea.’

“When we recorded Music From Big Pink Albert was astonished by the results of that record. And he so embraced it and made it his own and all that other stuff vanished. He was like ‘I knew it all along.’ It fit so perfectly into his scenario.

“Bob and the Band were so close to Albert. We had been through everything together. Like I say in the book we were like war buddies. And we had gone to the edge together. And because we had done all that stuff and The Basement Tapes, and through all of this, still had no idea of what this was going to be when we did it. That was thrilling.

“I didn’t plan to have cover versions from the album. That was a different kind of validation, yeah. I loved that.

“But we did have the experience with Bob Dylan and in doing The Basement Tapes with the songs that were supposed to be shared with other artists to record. It was because so many people recorded Bob’s songs and we were hooked up together, you thought ‘Oh. That’s part of it.’ And how that struck me I didn’t think about it in writing the songs or making the records that other people would do. This was a very interior thing. This was a thing between the five of us in the band. Something that we had collected over ages and pulled it together and made this gumbo.

“Bob already had such a track record that you thought people are going to be drawn to this. If he put something out there for people to record, people are going to be drawn to this. It just seemed to me that this was something he’s already established. So it wasn’t after we sent out these songs and everything and it wasn’t me saying this is exactly what it was.

“Bob was involved in it. Garth was involved in it. Right? And part of it was just in fun. You know, we would record a song like ‘You Ain’t Going Nowhere.’ And Bob would say. ‘Whatta you think. Ferlin Husky? Right? And it was half kidding around and half meaning somebody is going to but with the way that he is and the way that he thinks too Bob that he could insist on sending that song to Ferlin Husky first. You know what I mean? Just because he would do something like that. But when we said ‘OK. We’ve got to pull some of these things. We were recording a lot of stuff. We were covering songs and just having fun. And then every once in a while there would be an original one in all of this.

“And when we were doing this not with Bob, this was the germs and the idea and the beginning of Music From Big Pink. That was happening kind of in the back room too. So when we chose those songs to send out we were choosing what we liked. We were kidding around. I didn’t notice Manfred Mann could do a really great job on ‘The Mighty Quinn.’ I didn’t know that. But we were saying ‘that ‘Mighty Quinn’ thing has something to it.’ It really was what felt right in putting that collection together.”

The Band relocated to Hollywood to cut their second album. Was there a reason for this decision?

“We came to do it in Hollywood because it was too cold in Woodstock. (laughs). And we were from Canada. So we knew cold and we knew when to get out of the way. So we thought, ‘wouldn’t it be wonderful to go and do this thing and go outside, where it feels beautiful and sunny and everywhere else it’s stormy. It was a good feeling inside and we felt we were getting away with something.

“Before Big Pink, I had had this dream of having a workshop. A place. A sanctuary where we could go into the privacy of our own world and do something and not be on somebody else’s lawn, to really be in our own environment, let alone away from studio union breaks. We go into a studio and the guy is like, ‘Well, it’s almost 4:00 p.m.…’ So all of these things are playing into it a little. Although the experience in the studio of recording Music From Big Pink was fabulous.

“The producer John Simon was great and the engineers were great at Phil Ramone’s A&R Recording, but the idea of having this private sanctuary and that it would have its own sound, its own sound and its own flavor. That’s where that Les Paul thing came back into the picture.

“It would be like Chess. We could have our own one. And it would not sound like any of these other places. Going into somebody’s environment and then saying, ‘You go over there. You sit here. And we’re gonna use this kind of microphone on you.’ I thought that was what you did with somebody else. ‘I feel like I’m getting seconds here.’

“I was thankful for that period of time too. Because it was now a period where an artist wanted to something that A&R guys like [Capitol Records engineer and staff producer] John Palladino had nothing to do with the music. He was never there when we recorded. No intrusion.

“So when I said, ‘we want to do this thing that started in the basement of Big Pink. We want to bring the equipment to us in our own atmosphere. And we want to record at whatever time we feel the spirit. We don’t want to be on somebody’s clock,’ John was like, ‘OK.’ ‘We just need the equipment to come to us.’ And he had to kind of go along with it, you know, but he didn’t understand it.”

Here’s a regional fact that informed the sound of The Band. The drum kit with wooden rims that Levon Helm used on the album was found at a pawn shop in Hollywood on Santa Monica Blvd.

In 2018 I spoke with drummer Jim Keltner who was invited to a recording session in spring 1969 for a track appearing on The Band.

“I was playing with the Charlie Smalls Trio. Wilton Felder was the bass player. Charlie sang and played piano. We had two great girl singers. Charlie later wrote the big Broadway hit, The Wiz, which they later made into a movie.

“We worked the Daisy Club in Beverly Hills a few times. We were going to play the evening of [June 5, 1968] for a victory party when Robert F. Kennedy got shot.

“I met The Band through my dear friend and the amazing bassist, Carl Radle. We were with Gary Lewis & the Playboys. Leon Russell was the producer and arranger. We were all from Tulsa, Oklahoma.

“Carl took me up to Sammy Davis Jr.’s house high up in the Hollywood Hills where the Band were doing their second album for Capitol. They had a studio set up in the pool house. I think they had an eight-track machine. Carl knew Levon and the guys and he was the one who turned me on to the Music From Big Pink album. That album blew my mind. I listened to it all the time. I thought they were all Southern guys. And it was kind of a shock when I met them. Levon was the only guy from the South.

“If you are a singing drummer you have a great advantage. I’ve always played to the vocal and I found out that Ringo and countless other drummers, I’m sure, do as well.

“Levon was able to push or pull the groove any way he felt it by singing and playing at the same time. The way he felt space was magnificent. His biggest influences were the blues bands he heard as a young man. The geniuses from the Delta and around where he was from.

“So to hear that Big Pink LP and then go to a couple of tracking sessions in Hollywood for their next album and to hear Levon singing and playing with one of the greatest singing bass players, Rick Danko, who always made me wanna cry. Such a sweet soulful voice. And Richard Manuel was the voice that sounded like it was coming straight from heaven. Garth Hudson creating a totally unique sound for the Band. His keyboards seemed to have a voice just as soulful and timeless as Rick and Richard’s. And, of course, those epic songs and perfectly formed guitar parts and solos of Robbie Robertson.

“I was in New York in July 1969 with Delaney and Bonnie. One night I ended up at the Hit Factory, I think, could have been A&R studios. John Simon and Robbie and the guys were mixing ‘The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down.’ They had recorded the track a few weeks earlier in Hollywood.

“I can’t even begin to describe what that scene was like. I was sitting in the back on a couch watching this happen. There were four or five pairs of hands all over the studio console. The song seeped into my soul so much so that later when I would hear it on the radio and remember that evening with those guys as they mixed I would just cry. It still gets to me when I hear it.

“Levon makes you believe this guy Virgil Kane and his deep Southern pride. I am so glad I met Levon as early on as I did. His goodhearted soulfulness helped change my outlook on music and people. I will never tire of hearing the Band play and sing those great songs.”

Besides the sessions at Sammy Davis, Jr’s converted studio, "Up on Cripple Creek," "Whispering Pines" and "Jemima Surrender" were cut in New York at The Hit Factory.

The new expanded edition of The Band also incorporates the group’s August 1969 booking at the Woodstock Festival in Bethel, NY.

Promoter Michael Lang suggested to their manager, Albert Grossman that they close the Aug. 17 event. The Band were joined by Jefferson Airplane, the Who, Joe Cocker, Country Joe & the Fish, Janis Joplin, Johnny Winter, Ten Years After, Sly & the Family Stone, Blood, Sweat & Tears, Crosby, Stills, Nash (and Young), the Paul Butterfield Blues Band, Sha Na Na, and Jimi Hendrix.

“Woodstock. The ultimate calamity,” the Grateful Dead’s Jerry Garcia reminisced to me in a 1976 interview for the defunct Melody Maker. “It was raining and it got dark and we went on. There was maximum confusion going on about sound logistics. Really weird. Plus I was high, of course. And I went onstage in a state of confusion. The stage had sheet metal on it. It’s wet, and I’m getting incredible shocks from my guitar.

“It’s dark, and you don’t see any audience, but 400,000 people are out there. Then, somebody says the stage is about to collapse. I’m standing there in the middle of this trying to play music. Then they turn on the lights, and they’re a mile away. Monster super troopers. Totally blinding and you can’t see anything at all.

“Here’s this energy and everything is horribly out of tune. ’Cause it’s all wet, damp and humid. It was humbling. [Laughs.] That was a total disaster from our point of view. We played probably the worst set of our career. I’d like that one erased from the books.”

For the first time, this 11-song performance can now be heard in full as part of the Super Deluxe boxed set. It was The Band’s second show and it focused heavily on songs from Music From Big Pink, including “The Weight,” “Long Black Veil,” “Tears Of Rage,” “Chest Fever” and “This Wheel’s On Fire,” as well as their rendition of The Four Tops’ “Loving You Is Sweeter Than Ever.”

“I’ll tell you something. It doesn’t matter if there’s 30 or 300,000—once you get in front of people, you have to do something,” Robertson told me in a 1975 interview for Crawdaddy “The festivals are for people to get together. Who is playing is secondary.

“Anytime we’ve done those things, we’ve never really felt natural about doing it. We played the large dates because some terrific people were involved or we admired the other acts and they asked us to. We’re a puppet show in the distance, and the music is an excuse.”The Band explores America’s thorny history through indelible archetypes — “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down” refers to Union cavalry officer George Stoneman’s attack on southwestern Virginia in the last days of the Civil War, “King Harvest (Has Surely Come)” is sung from the perspective of a poverty-stricken farmer who becomes a “union man” to his disappointment, and “Up on Cripple Creek” is about a truck driver’s debauched time with a local girl in Lake Charles, LA."

It’s fitting then that the first song the group recorded for The Band was “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down,” a Civil War story that was inspired by a visit Robertson made to Helm’s family in Marvell, AK. During one of their talks, Helm’s father insisted to Robertson that “The South will rise again!” “I felt that I understood something about Levon from meeting his family,” Robertson says. “I wanted to write a song that he could sing better than anyone in the world.” The song imbues the people of the South with a forlorn dignity much in contrast to their stereotypical portrayals in popular culture—and Helm’s heart-rending vocal tells the song’s story with consummate grace.

This was not subject matter that other songwriters were mining from at the time and illustrated how The Band’s primary songwriter, Robertson, did not draw inspiration from typical rock sources, instead pulling from history and his love of classic films and screenplays.

I asked Robbie Robertson in our 1975 Crawdaddy interview about crafting autobiographical songs and employing a third person narrative in some of his tunes heard on The Band.

“I just think it’s part of storytelling,” Robertson reinforced. “It isn’t anything to put the songs in the third person. Sometimes when you get that little detachment you can write about more. I’m Canadian and I wrote the song about the Civil War [‘The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down’]. I didn’t know the story and it fascinated me. Everyone else took it for granted—they read about it in history class. When it’s strictly about yourself you’re ‘not allowed to deal with fiction.’ So it’s something that opens the gates a little bit,” he volunteered.

I’ve been at Village Recorders in West Los Angeles many times over the last few decades where Robertson has recorded for the last 44 years and quite aware of the studio's history. It’s a 22,000-square-foot former Masonic temple long championed by such artists as Jim Morrison, the Rolling Stones, Steely Dan, and Jimmy Smith. Geordie Hormel, a musical composer, equipment dealer, and entrepreneur founded the facility in 1968.

I always wanted to know why the Band and Bob Dylan selected Village to record Planet Waves and mix the 1974 live Before the Flood album.

“I moved out to Malibu and Bob and I were hanging out. We’d been talking about a tour for years. All of a sudden it seemed to really make sense. It was a good idea, a kind of a step into the past. We felt if there’s anything that everybody expects us to do, that’s what it is. We quickly decided it was a good idea and a new day. The other guys in The Band came out and we went right to work. We started rehearsing anyway, so we thought we’d do the Planet Waves album and get back to rehearsing, and that’s exactly what we did.

“There weren’t many studios in this side of town. And when I came out from Woodstock and New York to the west coast, and I write about it in the book too, that David Geffen convinced me to go to Malibu. At the time I don’t know if I had ever been to Malibu. You know what I mean? We might have driven down there in an afternoon or something, but I didn’t know what Malibu was. So it just shows you how good David was in convincing me of something.

“Anyway, it was all west side. And Village was the only studio. And it was new. And my current room, my office, was studio C. The first room in the building. Where people recorded. And tons of people made records in this room. When I came along I took over this room. That’s why the office has this big window. Because it was the actual studio. Then they built studio B. I don’t know why they started with a studio C. Maybe Geordie Hormel [original owner] thought ‘Oh. I’m gonna add and do stuff.’ Then the next room was B, and then studio A. And then studio D. And now there is other stuff upstairs.

“So the fact that it was on the west side was rule number one. Rob Fabroni was already here. When you came here to record he was the engineer who came with it. And Rob was terrific. I’ve done a ton of stuff here. It’s a west side story.”

In the RCN 2017 conversation, we touched on the November 2016 Rhino Entertainment 40th Anniversary Editions of The Band’s The Last Waltz in various CD, Blu-ray and vinyl formats.

On Thanksgiving Day 1976, the Band took the stage for the very last time at the Winterland Theater in San Francisco, CA. For the landmark show, Rick Danko, Levon Helm, Garth Hudson, Richard Manuel, and Robbie Robertson were joined by an all-star group of music pioneers and recording artist friends, including Paul Butterfield, Eric Clapton, Neil Diamond, Bob Dylan, Ronnie Hawkins, Dr. John, Joni Mitchell, Van Morrison, Muddy Waters and Neil Young, among others.

The roots of The Last Waltz began when Jonathan Taplin, executive producer of the film, who had been the Band’s road manager for four years, and had produced Scorsese’s breakout film Mean Streets, introduced Robertson to Scorsese, who had helped edit Woodstock and Elvis On Tour. “I couldn’t let the opportunity pass,” Scorsese explained. “It was this crazy desire to get it on film, to be a part of it.”

“The idea was to get the most complete coverage possible, so our 35mm cameras were scanning and zooming for the action,” continued Scorsese. “When Bob Dylan shifts from ‘Forever Young’ to ‘Baby Let Me Follow You Down, the film truly documents Robertson, Helm, Hudson and Danko adjust and play on.”

“I remember Marty saying,” Robertson mentioned, ‘This is something you never see. You’re never in on this.’”

The Last Waltz became the first concert documentary to be shot in 35mm, and influenced future music documentaries. “We live so emotionally and powerfully through those moments,” Scorsese felt. “The picture, for us, was so powerful. And it was bringing these emotions to us, creating the psychological atmosphere that I couldn’t verbalize then. But it was pretty scary. As exciting and as fulfilling creatively as it was, it was extremely frightening.”

“There was something about this period from the ‘60s through the ‘70s, everybody had a pretty good run,” Robertson offered. “When you watch these things over and over again, and how stirring these performances were, you’re almost seeing inside the whole era.”

I was at The Last Waltz and glimpsed in in the movie. It was theatrically screened in April 1978 to critical acclaim. The Last Waltz is still considered by many to be the greatest concert movie ever made.

Muddy Waters’ appearance was staggering.

Robbie marveled as well, “Because now when I’m watching it I’m also hearing it that way and the power of it. And what this man, and you look at him and say, ‘this guy…I don’t know what the Rolling Stones would have done, or a lot of music would have existed if it hadn’t been for this guy.’ And look at him, and can’t you see why?

“It is one of the high points for me in this. And just talking about pedal to the metal, and pulling the trigger, and he must have been about 65 or so, he came out and he was the daddy of the whole Delta blues scene for sure, but such a gentleman. He came out there with people who are so large and their own music, and held his own at 64, or 65, and didn’t take a step backwards. There’s a true master.”

Did Robbie and The Band members have interaction with Dylan before the show regarding song selections?

“For sure,” underscored Robertson. “We all through our thoughts into the hat and then we would try stuff, and if it felt right, then we just did it. It was one of those things like letting some higher power make the decision because the proof was in the pudding. And “let’s play that song and see how it feels.” We would that and say, ‘that was fun. Let’s do that.’ But Bob wanted to do stuff that was connected with our origins together, which is why we did ‘Baby Let Me Follow You Down,’ which we played back then, and ‘I Don’t Believe You (She Acts Like We Never Had Met).’ And having a thread going back to 1965-1966, and because it felt real. And obviously ‘Hazel’ and ‘Forever Young,’ because us working together on Planet Waves.

“So it was trying to find a connection, and not just do something that nothing to do with anything. We wanted it to have some thought. Nobody suggested ‘Hazel’ but Bob said I think we should do ‘Hazel.’

“One of the things I’m excited about on the (new) Last Waltz is that we got to use ‘Hazel.’ But you know when we were saying, ‘OK. Out of all of the songs we can do together what do you think we should do?’ It was like we’ll do some of the stuff from the 1965-1966 period. We’ll do something from Planet Waves we had just recorded it a couple years earlier. And in mixing it up we ran through a bunch of crazy ideas too.

“Like Bob said ‘should we do a Johnny Cash song?’ And he would start singing a Johnny song and we all knew this was never gonna fly. But it would be fun to play it. We’d play through it and say. ‘Naw.’ But all of this stuff, it was really like throwing things up in the air and see where they would fall. But Bob said, ‘you know one song I think we should do is ‘Hazel.’ We were like ‘Really? OK. Let’s do it. And we ran through it and it felt pretty good. ‘All right.’ But we knew we wanted to do ‘Forever Young.’ Because it connected to the occasion with all the people there and this generation and all of this stuff like Dr. John singing ‘Such a Night.’

“We had to make sacrifices originally, obviously, in the movie, because it’s a movie, and you have to edit a movie so it plays. But on the record we had a limited amount of space, too. And I was always taken by Bob’s performance on ‘Hazel.’ I thought he did an amazing performance on it and poured such passion into this song.

“This is the real thing in a setting of such respectful elegance and everything that when I was working on it I did think, ‘My God, I’ve known Van Morrison for all these years, I’ve seen him perform many, many times and I never saw him do what he did.’ Muddy Waters coming out there between all of these people and rock the very foundation of music in that whole place that night. This was like an outstanding experience. Sometimes I had to just catch myself not to be standing there with my mouth open."

I asked a Robbie a question about revisiting The Band catalog.

“I just feel extremely proud in the choice that we made to work together. I absolutely feel there are moments when I think…Whew…He’s the business. What talent. What an amazing emotional musical choice was made right there. I do feel those things,” he disclosed.

Inspired by his decades of creating and composing music for film and filled with a set of songs exploring the darker corridors of human nature, Robbie Robertson’s aptly titled, evocative 2019 solo album Sinematic came out via UMe.

The 13-song self-produced collection is Robertson’s first new studio album since 2011’s introspective How To Become Clairvoyant.

It’s less an album and more like a film, inasmuch as how the narrative and stories are conveyed. Throughout the entire body of work, Robertson is scriptwriter and director—building his stories around a myriad of colorful tones and sonic textures that unfold over the course of each track.

While making Sinematic, Robertson reached for what he affectionately refers to as his "black box"—a BAE Audio Royaltone stompbox.

Royaltone is an unorthodox fuzz box that delivers authentic English fuzz tones — in stark contrast to the hordes of cheesy, thin sounding fuzz boxes that have infiltrated the market. Royaltone harkens a lost era of '70s inspired fuzz tones, all captured in a rugged stompbox built to inspire new ideas and sonic textures.

“When I found the Royaltone, it seemed like it was part of a family of organic sounds,” said Robertson in a media release about the product.

“And most of these distortion pedals I find pretty boring, really. I like a real distortion where the speaker is crying out of the amplifier. For me, the Royaltone was like ‘Whoa! This is part of a sonic experience that fit right in, and not going to an ordinary place.”

Robertson employed a kind of "workshop attitude" in composing and recording Sinematic, working alongside many first-rate musicians.

“For my guitar work on Sinematic, I didn’t want any ‘acrobatics’. Anything remotely acrobatic, I got rid of. In my playing on this record, I was really trying to find the poetry, and relay a sonic experience that was telling a story. For me, sometimes a song is able to come out of a sonic experience. It isn’t necessarily just chord changes, a beat or a lyric. It can be a sound, and I just think, ‘I want to follow that. I want to go deeper into that place.’ And sometimes, with the help of technology, it can be like stirring up a potion.”

The first song on the album, “I Hear You Paint Houses,” features a duet with Van Morrison. On the track that follows, “Once Were Brothers,” Robertson collaborates with Citizen Cope and J.S. Ondara on vocals, as he relays a heartfelt homage to the brotherhood he felt as a member of The Band.

Other musicians on Sinematic include Pino Palladino on bass and Chris Dave on drums. Of the collaborative nature of the album, Robertson says, “this mixture of things and people that I cast in these parts for these little movies I’m making — some people call them songs — are all approached as a cinematic experience and executed in a workshop format.”

For his new album, Robertson drew inspiration from his recent film score writing and recording for director Martin Scorsese’s eagerly anticipated organized crime epic The Irishman, as well as the forthcoming feature documentary film, Once Were Brothers: Robbie Robertson and The Band, based on his 2016 New York Times bestselling memoir Testimony.

“I was working on music for The Irishman and working on the documentary, and these things were bleeding into each other,” says Robertson of the impetus for Sinematic.

“I could see a path. Ideas for songs about haunting and violent and beautiful things were swirling together like a movie. You follow that sound and it all starts to take shape right in front of your ears. At some point, I started referring to it as ‘Peckinpah Rock’,” a nod, Robertson says, to Sam Peckinpah, the late director of such violent Westerns as The Wild Bunch.

Inspired by Robertson’s acclaimed 2016 autobiography, Testimony, director Daniel Roher’s Once Were Brothers documentary explores Robertson’s young life and the creation of The Band, one of the most influential groups in the history of popular music. The compelling film blends rare archival footage, photography, iconic songs, and interviews with many of Robertson’s friends and collaborators, including Martin Scorsese, Bruce Springsteen, Eric Clapton, Van Morrison, Peter Gabriel, Taj Mahal, Dominique Robertson, and Ronnie Hawkins.

Robertson’s Testimony book and companion album deftly complement one another to capture time and place--the moment when rock 'n' roll became life, when legends like Buddy Holly and Bo Diddley crisscrossed the circuit of clubs and roadhouses from Texas to Toronto, when the Beatles, Jimi Hendrix, the Rolling Stones, and Andy Warhol moved through the same streets and hotel rooms. Robbie bumped into them all: Otis Redding, Marlon Brando, Charles Lloyd, the Crystals, Curtis Mayfield and the Impressions, Doc Pomus and Mort Shuman, Aaron Schroeder, Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller, Morris Levy, Ahmet Ertegun and Jerry Wexler.

In our 2017 dialogue, we talked about Testimony.

“I tried typing it on computer. I tried Dragon dictation. I tried everything and I ended up writing it long hand. And as I did it I thought ‘this is going to be around 400 pages, somewhere in that vicinity. And when I gave it to the publisher they said, ‘in book form this would be something like 840 pages.’ So I thought ‘I didn’t know what I was doing.’ So I had to do some cutting. There were a lot more stories and a lot more detail in it. Then I went to work in cutting it down to 500 pages.

“I wanted to do the structure thing like I said in the beginning where I start with the musical journey. I start with that. Then I can go back and talk about what got me to this place. I could do that. And after a while I’m on this train. I’m on this path and then I’m talking about another path that goes along parallel and that goes along side of it. And one catches up with the other one. And then they become one after a while. So that was the way. And I didn’t want it to be scattered. I wasn’t trying to do this to make it confusing. I was doing this to help the story right. Once I got up to a certain point and these two parallels came together then I was kind of off and running.

“So these stories got so heavy from carrying them around all these years that when I got to this place I thought ‘I can’t carry them all anymore. It’s too much.’ And writing this book I felt like ‘I can unload this.’ I feel lighter. I feel like now I don’t have to tell these stories anymore. I can hand you the book. (laughs).

“What I wanted to do was I wanted to start with music, but not that I was dipping my toe in the water. I wanted to start where the mission began. And the mission began when I took a train from Canada down to Arkansas. As I call it in the book, ‘to the fountainhead of rock ‘n’ roll.’

“Riding on that train going down there and the feeling that that gave me at age 16 was so pivotal, was so deep in my overall journey. In my whole experience that I thought, ‘That’s where I’ll begin.’ And then I’ll do these flashbacks to what got me to the train.

“One of the things that I really took away from that was that Doc Pomus and Mort Shuman or Leiber and Stoller, or Otis Blackwell, and a thing I had to cut out with Titus Turner, who was an incredible character.

“Anyway, one of the things I really got from them, because the obvious thing was that they tapped into something that felt good. But it had to feel good. The song could be about anything but it had to feel good. And I was like. ‘Wow…’ It would be one of the guys sitting at the piano playing. ‘Let me think of something. What about this?’ And they would start to play something. I was studying. I didn’t know what the song was about but it feels good. So I just thought coming in that door, coming in the back door of something, that when you start this thing if it doesn’t feel good then stop right now. ‘Ah ha. That’s something.’

“I thought who would think in their wildest imagination that Tin Pan Alley was a real place. The Brill Building and then Donnie Kirshner’s thing. All of it was actually in a place you could go. And the doors were golden when you walked in. And inside there in all these rooms were people who wrote songs and sent them out to the whole wide world.

“I had such a respect and a connection feeling for these people. And I knew Doc and Mort all of their lives. Doc and Mort remained friends. And I recorded with John Hammond, Jr. on an album that Leiber and Stoller produced. I was friends with Jerry and Mike, so to say none of that rubbed off on me just wouldn’t be true,” underlined Robertson.

“I wasn’t the lead singer in The Band. I don’t know if the Brill Building influence was that specific on arrangements and voices but I did try and soak up as much as I possibly could from the guys.

“So to say none of that rubbed off on me just wouldn’t be true. And it was stuff that I don’t know that if you grasp it on the surface but in a way of seeing the way these guys could adapt to these different artists. And they could write something and then cast it. Or, someone could say, ‘we need this. We’re coming to you.’ And they could write for that. And I thought that was a special gift. And I was doing that in The Band.

“I thought my job was in this was what they were doing too. My job was to say, ‘I’m going to write a song that Richard Manuel could sing the hell out of. I know what to do with his instrument.’

“Then, the other door was Bob Dylan who it wasn’t about that. It was about emotion and an energy, but it was really about saying something. It wasn’t about ‘these words could be anything.’ No. No. It was specific. So to me it was rebelling in a beautiful way against this other thing.

“I thought the sound was really important to me too. It still is. My first attraction to rock ‘n’ roll was just as much the sound was the song and the song was the sound. So when I heard these early Sun and Chess Records, I thought, ‘what is going on here?’ Before that, Les Paul and Mary Ford. This sound thing. Because records before that you didn’t think that much about the sound. It was a vocalist and some music in the background.

“When rock ‘n’ roll came along there was coming out of these different studios from places in Texas, Memphis and New Orleans. The sound of the records coming out of New Orleans that was [engineer and studio owner] Cosimo [Matassa]. What is going on here? The sound coming out of Chess Records in Chicago. I thought ‘what kind of a room is that? What is this magic?’”

Once Were Brothers was made in conjunction with Imagine Documentaries, White Pine Pictures, Bell Media Studios, and Universal Music Canada’s Shed Creative, the project is executive produced by Martin Scorsese; Imagine Entertainment chairmen Brian Grazer and Ron Howard; Justin Wilkes and Sara Bernstein for Imagine Documentaries; White Pines Pictures’ president Peter Raymont, and COO Steve Ord; Bell Media president, Randy Lennox; Jared Levine; Michael Levine; Universal Music Canada president and CEO Jeffrey Remedios; and Shed Creative’s managing director Dave Harris. The film is produced by Andrew Munger, Stephen Paniccia, Sam Sutherland, and Lana Belle Mauro.

Magnolia Pictures acquired the worldwide rights. “Being a longtime fan of The Band, Once Were Brothers: Robbie Robertson and the Band still held many surprises and information I didn’t know,” Magnolia president Eamonn Bowles said in a press release in 2019 announcing the deal. “Daniel Roher has fashioned a stirring tribute to a great American ensemble.”

The documentary was premiered Sept. 5 as the Opening Night Gala Presentation for the 44th Toronto International Film Festival.

In February the New York City premiere will be on Feb. 11 at the Walter Reade Theater at Lincoln Center. It will open in Los Angeles at the ArcLight in Hollywood on Feb. 21. Movie opens nationally on Feb. 28.

In late January, I was invited to the special screening Robertson, CAA Music, Brain Grazer, Ron Howard and Imagine Documentaries hosted at the Ray Kurtzman Theater in Los Angeles. Rob Light of CAA introduced the movie.

Robbie and I had a cordial chat. He complimented me on The Story of The Band From Big Pink to The Last Waltz, especially the chapter chronicling his experiences in the Brill Building.

Among the attendees: Ron Howard, Jonathan Taplin, Van Morrison, Jim Keltner and Cynthia Keltner, Michael Des Barres, Jimmy Iovine, John Scheele, Michael Ochs, Michael Simmons, Ken Sharp and Robertson’s manager Jared Levine, who initially suggested that Robbie hire Daniel Roher as the director.

You’ll be hearing a lot about Roher. There’s plenty of unseen photos and archival footage. The editing was dazzling. There were many new revelations and reel-to-reel truths on the screen.

Harvey Kubernik is an award-winning author of 16 books. His literary music anthology Inside Cave Hollywood: The Harvey Kubernik Music InnerViews and InterViews Collection Vol. 1, was published in December 2017, by Cave Hollywood. Kubernik’s The Doors Summer’s Gone was published by Other World Cottage Industries in February 2018. Harvey’s The Doors: Summer's Gone has been nominated for the 2019 Association for Recorded Sound Collections Awards for Excellence in Historical Recorded Sound Research.

During November 2018, Sterling/Barnes and Noble published Kubernik’s The Story of The Band From Big Pink to the Last Waltz.

In 2020 The National Recording Registry at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. displayed an essay Harvey penned on the landmark The Band album, that celebrated a 50th-anniversary edition in 2019.

. Kubernik is writing a book on Jimi Hendrix for Sterling/Barnes and Noble scheduled for publication last quarter of 2020.

In 2006 Kubernik spoke at the special hearings initiated by The Library of Congress that were held in Hollywood, California, discussing archiving practices and audiotape preservation.

Harvey Kubernik’s 1995 interview, Berry Gordy: A Conversation With Mr. Motown is in The Pop, Rock & Soul Reader edited by David Brackett was published in 2019 by Oxford University Press.

This century Harvey penned the liner note booklets to the CD re-releases of Carole King’s Tapestry, Allen Ginsberg’s Kaddish, Elvis Presley The ’68 Comeback Special and The Ramones’ End of the Century).