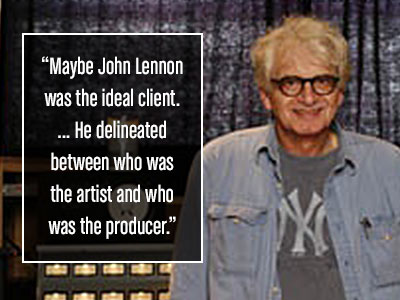

Jack Douglas

Clientele: John Lennon, Bob Dylan, Aerosmith

Contact: facebook.com/jack.douglas.773

In the ‘60s, Jack Douglas was a musician with a label deal in hand and stars in his eyes. Encouraged by the Isley Brothers, he was inspired to engineer and ultimately to mix and produce. The now legendary producer’s first taste of studio work came as a janitor at New York’s then-new Record Plant studios. As his repertoire expanded, he was tapped to engineer John Lennon’s Imagine and later to produce the former Beatle’s final album, the Grammy-winning Double Fantasy. Originally from New York, Douglas has worked in London and currently splits his time between L.A. and NYC.

What are some of the biggest challenges facing producers today?

Convincing major labels that, after mixing dozens of singles and albums, I can mix a record. When I’m hired to produce, I include a mix in the price. I’ve been told many times “But you’re not a mixer.” I find that challenging and hard to understand. It’s caused a lot of homogenization in pop music. But finding work isn’t difficult. There’s tons of it, as long as you keep all of the avenues open and are willing to diversify. But that’s only speaking for myself. I bet a big problem for a lot of producers is finding work.

What’s an ideal client for you?

There’s no such thing. They’re all different. I may work with a brilliant artist who’s a fall-down drunk. I may work with the nicest guy in the world, but he needs so much help with his music. Maybe John Lennon was the ideal client. He had more talent than he could ever imagine. He delineated between who was the artist and who was the producer. My job was to direct him and bring an objective opinion of his work. His job was to write and perform. It made working with him simple.

When does a producer become a co-writer?

For years I co-wrote with Aerosmith and didn’t take the credit. I thought that it was the producer’s job to facilitate the song in any way: writing bits and bobs and pieces along the way. I did that for a few albums and then caught on that I was missing a big chunk of dough. You start to see my name as a writer around [1977’s] Draw the Line. But I don’t jump in to write unless I’m invited or I feel the need. Otherwise it’s an intrusion. I have to write a big chunk [of a song] before I ask for a percentage. Not words here, chords there. That’s a producer’s job.

What’s your strategy for putting an artist at ease?

During pre-production, I like to discover what makes an artist tick long before we get into the studio so that I can facilitate his or her dream. When we do go in, we feel like we came together in the same car. I do pre-production with all of my artists. With a band like Aerosmith, it may last a month. Other artists come to me with a demo that’s worthy of release. I feel it out as I go.

What have been your favorite technical developments over the past few years?

Good copies of older equipment. Companies are making great stuff—reproductions of Fairchilds that sound better than [the original] Fairchilds. And these don’t have to be rack-mounted. They can be virtual. They’ve taken the [original] idea and improved on it.

How do you establish a strong relationship with a mastering engineer?

I have a 35-year relationship with everyone at Sterling [Sound], starting with George Marino and Greg Calbi. Aside from things done by Doug Sax or Bob Ludwig, Sterling’s done 80 percent of my mastering.

What are the best ways for artists to save money in the studio?

Own your own studio. No matter how big or small. Otherwise, be prepared when you go in. But allow for improvisation. Don’t be so stiff that nothing’s going to change.

What’s the biggest challenge you’ve ever faced in the studio?

I put a lot of pressure on myself. I’m a nervous wreck before I start a project—it doesn’t matter who it is. I’m challenged every time I go into the studio. I try not to show it, but internally there’s a bit of stage fright. Once it gets going and I see that it’s on course, everything’s fine.

What does the future hold for major labels?

To buy records cheaply that are already made and distribute them. This means whatever the record-buying public is into. They’re not going to take any chances. Major labels have lost their way. They’re only interested in pop, urban music, a little country and not much else. Fortunately, there are avenues for every kind of music. We don’t need the majors except to compete with artists in the mainstream genres.

Who are some of your dream clients?

The Rolling Stones. My buddy Don Was produces for them and he does it well. My other dream client was Bob Dylan and I’ve worked with him [on Allen Ginsberg’s 1983 record, First Blues].

What’s the key to identifying talent?

Originality. I don’t like chasing trends. Hearing something I’ve never heard before is what turns me on. It keeps me interested. •