-------

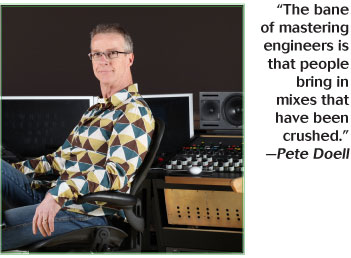

Pete Doell

Company: Universal Mastering

Clientele: Rachael MacFarlane, Frank Gambale, Adam Lambert

Contact: http://universalmastering.com, laphd@earthlink.net

Pete Doell spent 16 years working for Capitol Records as a recording engineer before moving to Sony Pictures where he scored films. Nine years ago he moved to Universal. There he’s labored as a mastering engineer and mastered more than 100 records. He recently completed work on the new Pete Escovedo project and will soon start on Steve Lukather’s record.

Pete Doell spent 16 years working for Capitol Records as a recording engineer before moving to Sony Pictures where he scored films. Nine years ago he moved to Universal. There he’s labored as a mastering engineer and mastered more than 100 records. He recently completed work on the new Pete Escovedo project and will soon start on Steve Lukather’s record.

What are the best ways to prep a mix for mastering?

Submit a 24-bit file. Bit depth is more important than the sampling rate. That gives me 50 percent more data, more depth and more full-figured sound. The bane of mastering engineers is that people bring in mixes that have been crushed with an L2 or some converter that takes away all of the dynamic range. That’s one way to make it loud but it also kills the vitality.

Which mix problems can be addressed in the mastering stage? Which can’t?

We often see too much or too little low end. That’s the result of mixing in a room where you can’t tell what you’re hearing. In the case of too much bottom end, it’s because you can’t hear enough of it in the mixing room so you add a lot. It’s a much easier patient to save if they come in with too much bass than if they come in with too little. If we add it here, it tends to make stuff like the voice or piano sound tubby.

Have the do-it-yourself mastering tools improved to the point that musicians can achieve a better-than passable master at home?

I was just working with a Kanye West project where they’d mixed it in Hawaii. They got it right out of Pro Tools and mixed with a Steven Slate digital plug-in, which is good but not as good as the [Universal Audio]. We added the metadata and sent it on its way. People can mix things now that sound “finished” but not necessarily great. The strength of going to a real mastering engineer is that you have a room that reveals everything.

What’s the ideal format for mastering-ready mixes?

A WAV file that’s 24-bit. Higher sampling rates are good. They sound like a rich, natural musical experience. Analog tape is great but no one can afford it. I use it as an insert on my console for stuff that’s mixed in the box that sounds a little brittle or thin. I can run it off the half-inch analog tape and put some meat on the bones. That’s especially effective with rock. I do that at least twice a week.

Do artists ever send you MP3s?

Only by mistake. It’s a terrible place to start because there’s so little data. We always send it back.

What’s your take on the Mastered For iTunes initiative?

We do a lot of it. We listen through the Sonnox Fraunhofer codec. You can check it in real time and hear what horrible things are about to happen to your mix. Some music passes through unscathed but sometimes we have to do stuff that’s akin to vinyl mastering. We might have to high-pass it because of issues with sibilance or extended bass.

What’s the biggest mastering challenge you’ve ever faced?

Meeting clients’ expectations. You know you’re in trouble when a client says “This does not have to be a loud record.” That will be the guy that wants it louder than loud.

What’s the biggest technical challenge/problem you’ve ever gotten out of?

Somebody brought in a DAT once and the two channels were out of phase. We had to split it up inside a workstation and phase-reverse one side.

What does the future of mastering hold?

It’ll be around a long time. Many records are being made in home studios. They’ll need to be checked in a room that’s revealing; so that it can be heard in a way it wasn’t when it was mixed.

What do you say to people starting out as mastering engineers?

Listen to a lot of music. The great thing about being a mastering engineer is that you don’t get pigeonholed. You bring your skill set to a plethora of music. That’s fun and rewarding.