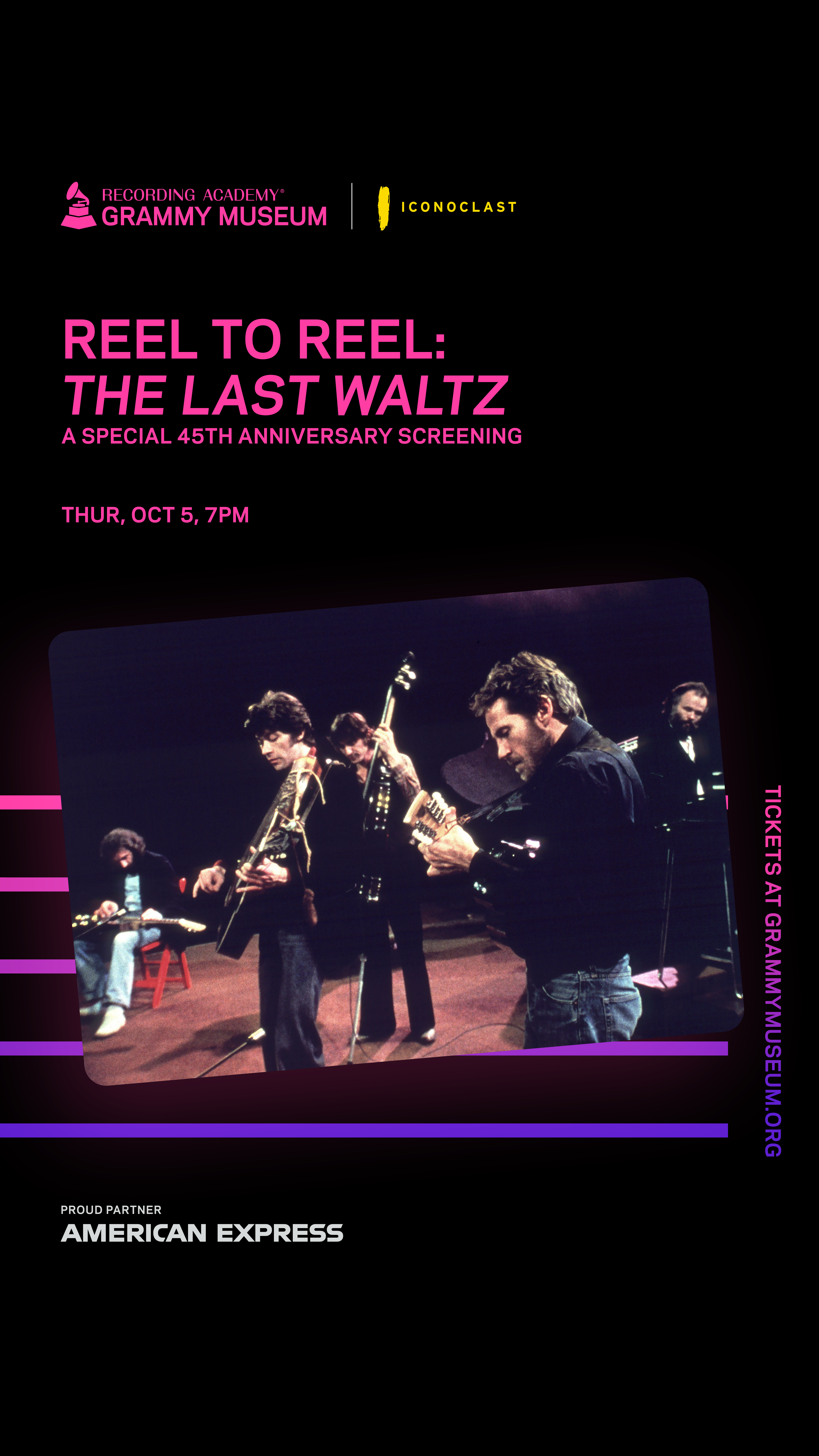

The Grammy Museum in downtown Los Angeles will continue their Reel To Reel series with a screening of The Last Waltz. It will be followed by a panel discussion with Olivier Chastan (CEO of Iconoclast), Mark Pinkus (President of Rhino Records), and myself.

The Last Waltz—director Martin Scorsese’s documentary capturing The Band’s 1976 farewell concert in San Francisco at the Winterland Ballroom received an official Criterion Collection release in 2022.

Scorsese’s 1978 film touts a 4K digital restoration and audio commentary from Martin Scorsese, Robbie Robertson, and Mavis Staples, and others, a new interview with Scorsese conducted by critic David Fear, outtakes, and additional footage. It was issued on Blu-ray and 4K UHD March 29, 2022.

Scorsese and seven camera operators lensed epic performances by Joni Mitchell, Bob Dylan, Van Morrison, Ronnie Hawkins, the Staple Singers, Muddy Waters, Neil Young and others, in addition to The Band’s goodbye concert.

Other features of the Criterion Collection incorporate a 1978 interview with Scorsese and Robertson, a 2002 making-of documentary about The Last Waltz, and an essay by writer and author Amanda Petrusich.

Before the legendary 1976 The Last Waltz event, The Band’s members shared an extensive collaborative history. Formed in Toronto, Canada, between 1960 and 1962, the then-teenaged multi-instrumentalists Levon Helm (drums, vocals, mandolin), Robbie Robertson (guitar, piano, vocals), Rick Danko (bass, vocals, fiddle), Richard Manuel (keyboards, vocals, drums) and Garth Hudson (keyboards, horns) first performed and recorded together as members of the backing band for Ronnie Hawkins, called the Hawks.

In late 1963, the Hawks became Levon & the Hawks, playing and recording under this name in 1964 and 1965.

In time, they hooked up with an oddball Arkansas rockabilly crooner named Ronnie Hawkins and became The Hawks, Ronnie's back-up group. Dubbing himself "The King of Rockabilly,"

In 1965, Robertson met with Bob Dylan in New York, just as Dylan was seeking an electric guitarist for his touring band. The Band was born, with all of the former Hawks backing Dylan on the road from October 1965 through 1966 as he incensed audiences in the U.S., Australia and Europe, performing electric sets. Disheartened by the vocally disdainful ‘folkie purist’ audience response to their first plugged-in performances with Dylan, Helm left the group in November 1965. Levon did not go along, however, embarrassed that his band was backing another. Drummer Micky Jones replaced him on 1966 world tour dates.

After the 1966 tour concluded, Helm re-joined The Band in 1967, as the group prepared to record their debut full-length album.

Their subsequent career since 1968’s Music From Big Pink, along with numerous album reissues and video/DVD/books, has been well-documented.

The roots of The Last Waltz began when Jonathan Taplin, executive producer of the film, who had been The Band’s road manager for four years, and had produced Scorsese’s breakout film Mean Streets, introduced Robertson to Scorsese, who had edited Woodstock and Elvis On Tour. “I couldn’t let the opportunity pass,” Scorsese explained. “It was this crazy desire to get it on film, to be a part of it.”

Scorsese, with director of photography Michael Chapman and a team of seven cameramen recorded the Thanksgiving Day 1976 concert event at the Winterland Ballroom in San Francisco that was produced by rock promoter Bill Graham. It was the same venue where they first debuted as The Band in April, 1969.

John Simon served as concert musical director. The Filmways/Wally Heider team of engineers was led by Elliot Mazer. The soundtrack was produced by Robbie Robertson, with co-production by Rob Fraboni and John Simon.

During 1976, Scorsese was working on New York, New York. At the same time, I was on that movie set, and interviewed Robertson for a Crawdaddy! magazine cover story in 1976.

I attended The Last Waltz with 5,000 people, reviewing it for the now defunct Melody Maker. I’m glimpsed in the film and conducted 1976, 2004 and 2017 interviews with Robbie Robertson, and The Band’s Rick Danko in 1977.

The Last Waltz captured the Band’s final live performance, shared on film and disc with Eric Clapton, Bob Dylan, Van Morrison, Ringo Starr, Muddy Waters, Emmylou Harris, Neil Young, Joni Mitchell, Neil Diamond, Ronnie Hawkins, The Staples Singers, Ron Wood, Paul Butterfield, Dr. John, Stephen Stills, among others. Howard Johnson led the horn section that incorporated arrangements written by Allen Toussaint, Henry Glover, Tom Malone and himself. The Band offered a repertoire that was culled from their entire catalogue to fans who also enjoyed a complete Thanksgiving dinner.

The first half concert portion opened with “Up On Cripple Creek” and covered catalogue from their Music From Big Pink LP through Northern Lights-Southern Cross. At intermission a number of San Francisco poets performed, including Michael McClure, Diane di Prima and Lawrence Ferlinghetti, owner of the legendary City Lights Book store. The Band came on stage for the second half, joined in order by Hawkins, Dr. John, Bobby Charles, Paul Butterfield, and Muddy Waters for a 16-song collaboration.

They continued the special melodic and musical evening playing their own tunes, including “Chest Fever” and “The Weight,” until the final guest of the event, Bob Dylan, joined them for five songs. All the performers then returned to the stage in a group sing-a-long of “I Shall Be Released.”

In addition, there were encores of two instrumental jams with Ringo Starr, Steve Stills, Ron Wood and Carl Radle. The Band returned to the stage for “Don’t Do It.”

In April, 1977 at the MGM soundstage in Southern California Emmylou Harris and The Staple Singers recorded “Evangeline” with The Band and “The Weight” for the film. In fact, The Band actually played “The Last Waltz” theme at the Winterland show, but were unhappy with the version at the famed gig.

Scorsese’s concert film included a photography team with Laszlo Kovacs and Vilmos Zsigmond.

“The idea was to get the most complete coverage possible, so our 35mm cameras were scanning and zooming for the action,” Scorsese stated. “When Bob Dylan shifts from ‘Forever Young’ to ‘Baby Let Me Follow You Down, the film truly documents Robertson, Helm, Hudson and Danko adjust and play on.”

“I remember Marty saying,” Robertson mentioned, ‘This is something you never see. You’re never in on this.’”

The film became the first concert documentary to be shot in 35mm, and influenced future music documentaries. “We live so emotionally and powerfully through those moments,” Scorsese felt. “The picture, for us, was so powerful. And it was bringing these emotions to us, creating the psychological atmosphere that I couldn’t verbalize then. But it was pretty scary. As exciting and as fulfilling creatively as it was, it was extremely frightening.”

The Band had a vision to create a concert and a film that would mark not only the end of their run together, but would magnify an end to a roots and blues-rock era that would be followed by punk rock.

“There was something about this period from the ‘60s through the ‘70s, everybody had a pretty good run,” Robertson offers. “When you watch these things over and over again, and how stirring these performances were, you’re almost seeing inside the whole era.”

Days before The Last Waltz concert, Scorsese had put together a 300-page shooting script that choreographed every camera movement to lyric and music changes. “No matter how prepared you are, you’re going to be subject to chance, to fate, to luck,” Scorsese stated.

“Everyone was so incredible about wanting to be involved with The Last Waltz, “volunteered Robertson, “come hell or high water. No one had to think about it; they just said they’d do it.”

In 2002, United Artists, MGM Home Entertainment, and Warner Bros./Rhino celebrated the 25th anniversary of the concert documentary limited theatrical release, special edition DVD and 4-CD boxed set of The Last Waltz.

Robbie Robertson and Harvey Kubernik 2002 and 2017 Interviews.

Q. Did you ever have any concerns while re-visiting The Last Waltz that you might turn out a soundtrack using the new technology without hiss and noise, which is part of rock ‘n’ roll, and that you might have a too sterile and too clean soundtrack in this new model?

A. Yeah. But with something like this, there are certain things that are part of the characteristic of it and I think you have to be careful when you go in. This is not doing surgery and trying to fix something that isn’t broken. I think that some of that can actually be complimentary and musical, just the same way that vinyl can be. It’s just getting it so it’s under control and it’s not overwhelming what the heart of the whole thing is.

Q. Did you have any doubts or fears embarking on The Last Waltz event?

A. Entering the event, big time, was ‘Can we pull this off?’ There’s a thousand things that can go wrong, and a couple of things that can go right here. ‘Are we going to nail this?’ ‘Are we gonna pull it off?’ “Is the film going to capture it?’ ‘Are they going to say after that the recordings we have are a disaster?’ There’s all those kind of technical concerns and just your ability to rise to the occasion and that moment. It wasn’t like we were stopping and doing the songs over and over, or that ‘I think we can do it better.’ There was none of that.”

Q. I know there was a short rehearsal time before the actual gig and subsequent film and original soundtrack album. I’ve always felt that the couple of days, instead of an extended “pre-production and lengthy rehearsal,” added to the existing vibe and execution of the show––a lot of politics and factors didn’t get a chance to enter the equation because you kept the original impulse on the music and short-term preparation. Like the rehearsals included on the new CD set.

A. Yea. Yea. That’s great. The rehearsals were a wonderful surprise for me. Because I didn’t know that any of these rehearsals were even taped. What they were doing was testing the equipment and just taped some of these things to make sure everything was working and that they were judging whether they were using the right microphones for certain things. That kind of stuff. So, that was just a lovely surprise to hear and also to hear the difference in what somebody might do when they’re working the thing out, and what they would do when the audience is there and the lights go on. The different whatever they put on it.

Q. When did The Last Waltz concert go into planning stages? I know when we talked in 1976, you admitted then you were tired of a routine of “album, tour, album, tour.” Did this begin to bubble in summer of 1976? Did the seeds of the event go back earlier?

A. No it didn’t. The idea came around and in probably September. Then I needed to talk to everybody about it and it had to germinate the whole thing. I needed to feel…What happened with the idea was that it almost once, and this is that I have found in my experience, this is the way things often happen. When you come up with something so right that it takes on a life of its own. And when I started thinking about originally that we were going to do this and who were going to invite, and we’d only talked about Bob Dylan and Ronnie Hawkins. And then there were other people who had been so supportive and that we respected so much musically, that we said, ‘If we’re gonna invite them, we shouldn’t forget Eric (Clapton ). Over the years I saw him a lot. The same thing with Van (Morrison). And then there’s our country men from Canada; Joni and Neil and the whole thing just snowballed in a way and it was almost like your job, a good portion of time was to get out of the way.

“Like rock ‘n’ roll, it’s definitely call and response. And that’s what happened. Then after I had an idea of the people we felt should be a part of this and when I went to the place of thinking about the musical people of that generation, and who had been so influential to that generation, ya know, talking about Muddy Waters and the Staple Singers, and all the parts and all of these flavors of music played into the whole picture, and that the horizon had such depth and such different flavors to it was really important to me and hoping that we could display all of that. That’s one of the reasons we went back later with Marty shooting on the MGM soundstages for three songs: ‘The Weight’ with The Staples; ‘Evangeline’ with Emmylou Harris; and ‘The Theme From The Last Waltz.’

“That’s one of the reasons we went back later to do this thing with The Staples Singers, and this thing with Emmylou Harris. We had done The Last Waltz and never paid that same kind of respect to the music that came down from the mountains, or whether it would be gospel or country or even ‘The Last Waltz’ theme which was so traditional and me just being a movie buff, ya know. I wanted to have something that was thematic to it and was absolutely as lovely as what Scorsese and (production designer) Boris Leven, the cinematographers and everyone were trying to do. People kept using the words ‘beautiful,’ and ‘that’s so warm,’ that you wanted to just go with that whole thing and everybody feeding of all that those different energies.

“So, the preparation for it, and the time I got to Marty it was probably six weeks away when I talked to him about it. That’s what I’m remembering. The timing wasn’t great for him but it was something that he was so passionately wanting to do, he made it work.

Q. You’ve seen it all from your own group’s gigs and to dates with Sonny Boy Williamson in the early ‘60s in a club where a single white spotlight was on the singer. Then, cut to The Last Waltz, where you have lots of cameras, additional lights, the chandeliers hanging above and around the stage at Winterland. The stuff had to be there to help document everything. At the time, were you aware of the camera and sound relationship? Did it inhibit your performance?

A. Yea, but I thought that it was important to know when to get out of the way, too. And when Marty invited Boris Leven the production designer to help us out with this, Boris Leven, with such respect to the guy who had done West Side Story, The Sound Of Music, and Giant.

Q. Marty brought in Michael Chapman as director of photography. Award-winning film veterans at the helm and not recent film school graduates and rookies who’ve done two music videos and then get a major feature film gig. And this is added to people like yourself and Jonathan Taplin (Band road manager/executive producer of the film) who truly emerged out of rock ‘n’ roll. That’s healthy.

A. For sure, but you know what? I think the healthiest thing is when you mix those worlds together and whether you’re mixing different elements of music together and coming up with something fresh, or whether you’re doing the same thing with film, or mixing music and film together in this case, it’s all about going somewhere that neither one of you would have gone on your own, and accepting God’s favor. And I’m not gonna sit around and judge every element that comes along. I asked Martin Scorsese to do this because I have great respect for him, and he has great respect for the music, and I’m just gonna let him do everything that his instincts tell him and he’s gonna let me do everything that my instincts tell me on my end.

“Everybody (The Band) was overwhelmed by how this thing caught fire. How exciting this was seeing this thing come together and just being surrounded by such brilliance. So, everybody was having a great time with that. It was, like all movies, and like any project this big that has so many people involved, this is a committee art, ya know. This is not one person doing anything. It’s many, many people participating.

Q. Did you have discussions about subject specific things, like not having a whole film of just close-ups or the camera fixed on the guitarist’s fingers?

A. We had conversations about just the approach of what we didn’t like about things that had happened in the past that we just didn’t want to do that. We wanted to do this in a much tastier fashion, in a classic fashion. And Marty was so in tune with that, and he said, ‘I worked on Woodstock, and that movie was about the audience. This movie is about the music.’ And this is getting people together who will never be together in our lifetime and an event that will never happen again. And he said, ‘I want to do this in a way that shows how much I care about what’s happening here. And how grateful I am to be part of this.’ And that’s where those choices were made. And we talked about things and how they would be shot, where the cameras would be. He went over that ‘cause he’s a very generous artistic person, plus he wanted everybody to be on the same page so we were all in a position to do what we possibly can.

Q: In 2016 there was a 40th anniversary edition box set of The Last Waltz out from the Rhino label, which has extra Bob Dylan songs on the soundtrack discs. Obviously, you had interaction about repertoire with Dylan before the show?

A: Oh, for sure. We all tossed our thoughts into the hat and then we would try stuff, and if it felt right, then we just did it. It was one of those things, like letting some higher power make the decision, because the proof was in the pudding. And “let’s play that song and see how it feels.” We would do that and say, ‘That was fun. Let’s do that.’ But Bob wanted to do stuff that was connected with our origins together, which is why we did “Baby Let Me Follow You Down,” which we played back then, and “I Don’t Believe You (She Acts Like We Never Had Met),” and obviously “Hazel” and “Forever Young,” because of us working together on the Planet Waves thing. So, it was trying to find a connection, and not just do something that had nothing to do with anything. We wanted it to have some thought. And in mixing it up we ran through a bunch of crazy ideas too. Like Bob said, ‘Should we do a Johnny Cash song?’ And he would start singing a Johnny song and we all knew it was never gonna fly. But it would be fun to play it.

“We’d play through it and say, ‘No,’ but all of this stuff, it was really like throwing things up in the air and see where they would fall. But Bob said, ‘You know one song I think we should do is ‘Hazel.’ We were like ‘Really? OK. Let’s do it.’And we ran through it and it felt pretty good. ‘All right.’

“Well, one of the things I’m excited about on the (new) Last Waltz is that we got to use this other Dylan song, ‘Hazel.’ We had to make sacrifices originally, obviously, in the movie, because it’s a movie, and you have to edit a movie so it plays. But on the record we had a limited amount of space, too. And I was always taken by Bob’s performance on ‘Hazel.’ I thought he did an amazing performance on it and poured such passion into this song. It became a whole other thing live. Exactly. And the difference in the passion level is just extraordinary.

“But we knew we wanted to do ‘Forever Young,’ because it connected to the occasion with all the people there and this generation and all of this stuff. Like Dr. John singing ‘Such a Night.’

Q: When we talked in 1976 about The Band playing with Dylan on the 1974 tour, you remarked “at least this past time we weren’t booed.” I still have a hard time this century comprehending Dylan and your group being booed on the world tour of 1966, when what I remember about the 1974 shows I saw, everyone was totally digging the blend on stage.

A: Getting back to your question about The Band and Bob on stage. There was a thing that happened between Bob and The Band that when we played together that we would just go into a certain gear automatically. It was like instinctual, like you smelled something in the air, you know, and it made you hungry. (laughs). It was that instinctual. And the way we played music together was very much that way. And whether we were playing in 1966, or 1976, or when we did the tour together in 1974, we would go to a certain place where we just pulled the trigger. It was like ‘Just burn down the doors ‘cause we’re coming through.’ And it was a whole other place that we played when we weren’t playing with him. It was a whole place that he played when he wasn’t playing with us, so it was like putting a flame and oil together, or something. I don’t know.

“When we did the Dylan and Band tour in ’74, where we went and did a lot of the same things we did back in ’66, and the people’s response was ‘This is the shit and I knew it all along.’ It was like you weren’t really there all along. It’s really a very interesting experiment to see, or go from something that people were so adamantly against this music, and that we didn’t change nothing, and the world revolved, and everybody came around and said, ‘This is brilliant.’ That was very interesting to see everything else change around you.

Q: Muddy Waters in The Last Waltz was incredible. He leaps out of the screen. When you were taking a look at this new print, and putting the soundtrack together, with two of his tracks, does he blow your mind, too, maybe because you captured something that people will never be able to physically see and experience?

A. More so. Because now when I’m watching it, I’m also hearing it that way and the power of it. And what this man, and you look at him and say, ‘This guy…I don’t know what the Rolling Stones would have done, or a lot of music would have existed if it hadn’t been for this guy.’ And look at him, and can’t you see why? It is one of the high pints for me in this. And just talking about pedal to the metal, and pulling the trigger, and he must have been about 65 or so, he came out and he was the daddy of the whole Delta Blues scene for sure, but such a gentleman. He came out there with people who are so large and their own music, and held his own at 64, or 65, and didn’t take a step backwards. There’s a true master.

Q. I had seen Muddy in clubs like The Ash Grove, thankfully, down the street from my high school in West Hollywood, with no age limit. At The Last Waltz Muddy had the best sound, the best lights, a huge stage, and lots of people behind him. Muddy really brought something to the party

A. Yep. Well you know there was something to the idea of when all these people are in this place, and you’re coming out and doing one song, or two songs, or whatever you’re doing, and then there’s all these people who had been out before you, and then all these people coming after you, all of that, it made everybody just rise to an occasion musically, spiritually that sometimes you don’t know you even have in yourself. That’s one of the things I think, ‘Thank God this was captured in such a beautiful way, too.’ And that you can really see this and really go inside it, and really feel a part of the whole thing, because it’s a movie. It isn’t just a video of something, where you looking at it and saying, ‘Is this fake?’ ‘Is this real?’ ‘Is this being fluffed up like a television commercial?’

“This is the real thing in a setting of such respectful elegance and everything that, when I was working on it, I did think, ‘My God, I’ve known Van Morrison for all these years, I’ve seen him perform many, many times and I never saw him do what he just did.’ Muddy Waters coming out there between all of these people and rock the very foundation of music in that whole place that night. This was like an outstanding experience. Sometimes I had to just catch myself not to be standing there with my mouth open.

“It’s done in a way that draws you. You’re no longer sitting in the audience in this thing. You are sitting right up in the stage in front of the music. And it just wraps around you. It’s really quite beautifully done.

Q. What was your first reaction on viewing the new cut of The Last Waltz and hearing the music?

A. Well, it’s pretty extraordinary to be able to see this better than it’s ever been seen, and to hear it better than it’s ever been heard and for it to be so much more encompassing. The whole experience, because now, with what you can do with technology, just the way that it looks that it’s richer, the blacks are blacker, the colors are warmer and when I was working on sound for it, they had a thing where you could A/B what it was, the old mix of it, and the new Surround Sound on it, and it was overwhelming the difference in it. And the way that I did this was to put the viewer in the best seat in the house in the audience so you can hear people around you, ya know, breathing, and screaming and carrying on. It really is such a different feeling from what it’s ever been and such a tremendous improvement.

Q. Did your own life flash in front of you when you saw the new print?

A. No, it doesn’t do that to me. I go into an automatic mode of doing the work. I go to a place of ‘Here’s what needs to be done,’ ‘Here’s what we have to address now,’ ‘I want to remember to get this right.’

“I don’t go down memory lane at all in these things. I really look at it like the work that needs to be done, or the work that was done, and how was it in this setting? Things like that. I automatically go there. And I don’t know if I’m cheating myself by not affording myself the pleasure of doing that, but it’s just not of my nature to sit back and, ya know, light up a pipe and just enjoy the experience for what it is.

Q. When you hear The Band’s music on the speakers, what do you think when it’s coming back at you? Is it a joyous experience? Is it a sad experience?

A. I just feel extremely proud in the choice that we made to work together. I absolutely feel there are moments when I think…Whew…He’s the business. What talent. What an amazing emotional musical choice was made right there. I do feel those things.”

-------

In 1977 I interviewed Rick Danko, the bassist of The Band for Melody Maker in the Century City office of Arista Records when he had just released his debut solo album, Rick Danko.

We chatted about The Last Waltz.

“The cameras didn’t inhibit anyone. We wanted to feed five thousand people a gourmet dinner, and I think we also gave ‘em a good show,” he winked. “You were there. You saw the concert. Wasn’t it terrific? We had people stashed behind the curtains giving us hand signals. The movie is a labor of love. At the start, The Band had to raise a few hundred thousand bucks so this event could become a reality. We we were taking a chance--we almost hocked our houses.

“We were the perfect house band. Even the rehearsals were incredible. It cost $125,000 to renovate Winterland. I hate to keep relating to money, but I want to show you how important it was for us to have the theme and décor amplify the mood of the celebration. It was a special night.

“Preparing for the gig was a trip in itself. For four days we did nothing but play music. We finished Islands our last album for Capitol, and then nonstop rehearsal for The Last Waltz.

“The Band really came alive that night. We were cruising the last year and it was obvious. We were on stage for six hours and the Band worked until 5 a.m. that morning. We rehearsed with Bob (Dylan) at the hotel. We played for 16 hours before the gig. The Band has always been into precision, like a fine car. We didn’t take it easy during preparation. I think that will show in the movie. No split screen stuff and very little backstage footage. No way was I gonna walk out on stage and wing it next to Joni Mitchell. And Muddy Waters… Wait ‘till you see Muddy in the film. We also did a version of ‘Mannish Boy’ at the hotel and nobody had a tape recorder. I was playing next to him and got chills. I think for Muddy and for Ronnie Hawkins, they arrived at the high point in their lives that night.”•

---------

(In 2020 The National Recording Registry at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. exhibited a Harvey Kubernik essay on the landmark album The Band, which celebrated a 50th anniversary in 2019. Sterling/Barnes and Noble in 2018 published Harvey and Kenneth Kubernik’s The Story Of The Band: From Big Pink To The Last Waltz.

Harvey Kubernik is the author of 20 books, including Canyon Of Dreams: The Magic And The Music Of Laurel Canyon and Turn Up The Radio! Rock, Pop and Roll in Los Angeles 1956-1972. For November 2021 the duo wrote the critically acclaimed Jimi Hendrix: Voodoo Child for Sterling/Barnes and Noble.

Otherworld Cottage Industries in 2020 published Harvey’s book, Docs That Rock, Music That Matters, featuring interviews with D.A. Pennebaker, Chris Hegedus, Albert Maysles, Murray Lerner, Morgan Neville, Dr. James Cushing, Steve Binder, Curtis Hanson, Michael Lindsay-Hogg, Andrew Loog Oldham, Dick Clark, Ray Manzarek, John Densmore, Robby Krieger, Travis Pike, Allan Arkush, and David Leaf, among others.

Kubernik’s writings are in several book anthologies, most notably The Rolling Stone Book Of The Beats and Drinking With Bukowski.

This century Harvey wrote the liner note booklets to the CD re-releases of Carole King’s Tapestry, Allen Ginsberg’s Kaddish, Elvis Presley The ’68 Comeback Special and The Ramones End of the Century). Kubernik is the Project Coordinator of The Jack Kerouac Collection, a box set of recordings. In November 2006, Harvey was a speaker discussing audiotape preservation and archiving at special hearings called by The Library of Congress and held in Hollywood, California).