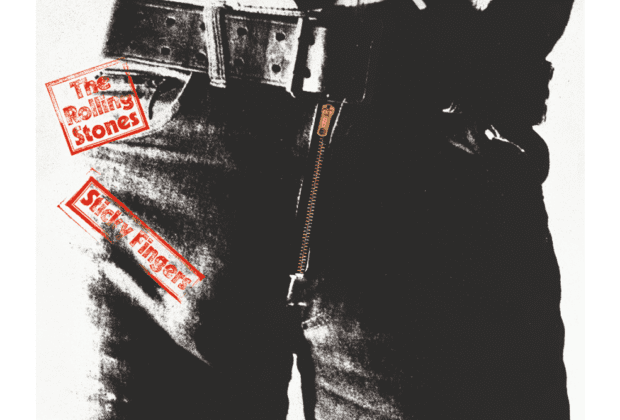

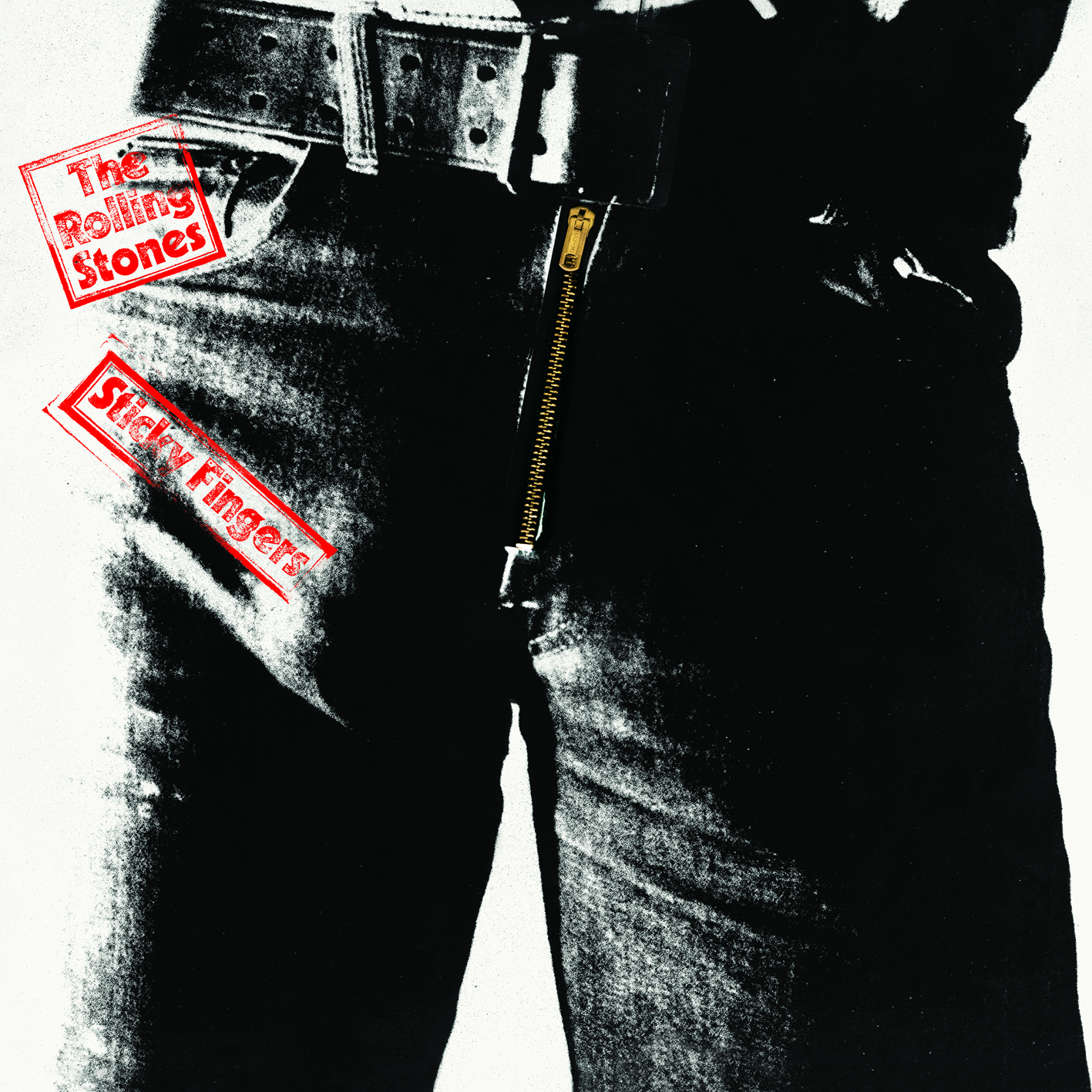

On April 23, 1971 Sticky Fingers was commercially released.

I purchased the LP at the world famous Wallachs Music City in Hollywood. It also featured artwork by Andy Warhol with its working zip on the front.

Sticky Fingers showcased the ever more inventive song writing of Mick Jagger and Keith Richards and formidable guitar licks from Mick Taylor, and bassist Bill Wyman, Jack Nitzsche’s piano work is heard on “Sister Morphine,” but I wished they spelled his last name correctly in the musician credits.

Veteran music business legend Marshall Chess is the son of Leonard and nephew of Phil Chess, the dynamic duo who founded the immortal Chicago-based blues Chess Records label.

In 1970, Marshall Chess became President of Rolling Stones Records 1970-1977, overseeing the original release of Sticky Fingers. Chess was Executive Producer on 7 Rolling Stone #1 albums during the 1970’s.

I conducted 2008 and 2010 brunch interviews with Marshall in West Hollywood at the Sunset Marquis Hotel. He discussed his life with the Rolling Stones and the 1970 and ’71 period that yielded Sticky Fingers.

“I worked on Get Yer Ya-Ya’s Out! I helped put it together and deliver it to London Decca. End of that contract.

“I knew Ahmet and Nesuhi Ertegun my whole life. We were very close. Ahmet called me initially. Mick, Keith and Charlie were very partial to Ahmet.

“Ahmet had a very winning personality with artists. And the Stones were very much into people connected to history. They wanted Ahmet. Then we began to negotiate the deal.

“I will say Ahmet’s brother, Nesuhi Ertegun, who gets way underplayed, the way they don’t talk about my Uncle Phil and just my father Leonard. Both of them were keys. Nesuhi was key to Atlantic, and they would not have been as good or near as good without Nesuhi, and nor would have Chess without my Uncle Phil. They always underplay these guys.

“Nesuhi ran WEA, the international side of that, and that was the first total synergy network, so when we released the Stones’ albums, it was a wave across the world. Global synergy. We timed it. We planned it. We had global distribution and we released it as a wave of publicity. With them we had the first totally coordinated world release. We could tour and the record was released the same day.”

John Paul Jones was having lunch at an adjoining table and I introduced the multi-instrumentalist/arranger and Led Zeppelin founding member to Marshall.

I mentioned to them both that I had just spoken in the morning with Andrew Loog Oldham, the Rolling Stones’ visionary manager, record producer and publicist from 1963-1967, who had produced Jones’ debut 1964 record, “Baja,” the flip side of Jack Nitzsche’s “The Lonely Surfer.”

Oldham also suggested his name change from John Baldwin to John Paul Jones, after seeing the film title on a Warner Bros. movie poster.

In 1964 and ’65, Oldham had arranged for the Stones to secure well-needed studio time at the Chess facility, and introduced the Stones to young employee Marshall. This century, Andrew and Marshall did a radio interview together for Little Steven’s Underground channel on Sirius XM.

Chess spoke fondly of his period with the Rolling Stones and his company’s first retail release.

“I think the label should be close to the artist. Even on a label like Chess, we were close. Not to every artist, but a lot of them we really were close. But the Stones were another thing. They became part of my life. At Chess no artist wasn’t part of my life. We were close to them. Like relatives.

“With the Stones I was family. And I felt it. They accepted me and I embraced it. It had a lot to do with my own psychological makeup. Because subconsciously, I was really upset that Chess Records had been sold. And it wasn’t left to me and I felt really ripped off. My father had died. I had a lot of problems that I had buried. And the Stones were a great way to forget about them. I was having a ball. Swinging London with the Rolling Stones. All of a sudden I had ten million people kissing my arse and following me.

“In fact, my memory is that we knew we needed a logo for the label, and we’re in Rotterdam, Holland, and I was in Amsterdam. I was driving to Rotterdam, a couple of hours ride. I stopped to get gas at a Shell Gas station. In Chicago, Shell had the yellow shell, and it spelled SHELL underneath. But, in Europe it didn’t say that. It was just the logo alone. That’s how strong their logo was.

“Remember, this is in Holland where Shell comes from. So, when I got to Rotterdam that night we were sitting around, smoking joints, whatever, ‘here’s the idea for the logo. It has to be strong enough to work without any print.’ That was where the idea came from.

“We hired many artists. I don’t exactly remember exactly where we came up with the tongue and lips, but we came up with the idea sitting around bull shitting, and I hired many different artists to draw many different versions. We had tongues waiving, tongues sticking up, different shaped lips, and a tongue with a pill on it. And then I remember buying it. We bought it out right from a London art student artist and designer named John Pasche. [Who then worked for Chess and the Stones until 1975].

“I was completely involved in the development. And, it was before compact discs, so the only place it said Rolling Stone Records we would inscribe it on the master on the edge around the label. I was also involved with the Prince, and the lawyers on the formation of the companies.

“When I think of the debut album, Sticky Fingers, I think of ‘Brown Sugar.’ The album cover, too. The album was a hot rock ‘n’ roll album with a great engineer. They were starting their new thing, new label, hot cover, new energy. I was around for all of it and the founding of the label.

“Here I was at Olympic studios. They were in a little corner. I watched the way Sticky Fingers was recorded. It was more an observation for me. I was not sure what my place was. I went to the studio a lot. Producer Jimmy Miller was a wonderful guy. I loved him.

“When I heard ‘Brown Sugar…’ Amazing rock ‘n’ roll just makes you grin. Then you get this confidence that ‘I’m gonna have a number one record.’ You get it. Then you call Ahmet [Ertegun]. ‘It’s a motherfucker we did last night!’ The energy starts building. You hold the phone up and give ‘em a hit. Then the cover ideas. It becomes your life. I’m not making any suggestions on Sticky Fingers. I’m keeping my mouth shut and I’m listening. I’m going to FM radio stations and living in London. Laying the groundwork.

“The band I saw live in 1971, the Marquee shows, was a different band from 1969. It expanded. My job at Rolling Stones Records was to get the music out. I did what I did very much at Chess what I did with them.

“What I brought to the Stones was and added to it was the attitude. ‘Fuck everyone. Fuck the label. Keep recording until we have a motherfucker.’ And I used to get called on the carpet. ‘You’re spending too much recording.’ ‘So what?’ ‘You want a hit?’ With Chess, the music came first. We knew we had the greatest music and the best chance of making money. That’s what I laid on them. Spend the money.

“I treat my people here very much like we treated the people at Chess. They are part of my extended family. It’s hard to put into words. Like, when I was running Rolling Stones Records, and working with the Stones as artists, you have to be on call 24X7. Dealing with talent and running a label. Discriminating the real talent from bullshit. And then respecting the real talent immensely. And showing them that you respect it. And, once they know you respect it, then you can criticize easier and help them.

“Like, I told Mick Jagger once, when I first started being like Chess to him, was during the recording of ‘Moonlight Mile’ for Sticky Fingers.

“I remember I was in the fuckin’ truck in Stargroves. And I kept telling him when he was doing the vocal ‘you can do it again motherfucker! Do it again motherfucker! Do it again!’ What I saw with everyone around the Stones they were so enamoured with the Stones everything was great. Even shit. But I was taught by my father and uncle that you push an artist past the event, you push an artist and somewhere down there will be his best take.

“So I think I did that with the Stones, and I really have no qualms of saying I spent as much time, or even more time than anyone, except Mick and Keith in the studio on my seven Stones’ albums. More than Charlie, more than Bill, more than Mick Taylor. More than Ronnie. I came to the full mixing and the overdubbing.

“I loved Mick Taylor in the Stones. That was great. Because I liked Mick Taylor’s feminine warm sounds intertwined with Keith’s masculinity. And I felt Ronnie was brilliant. I knew him from the Faces, Ronnie is like Keith. It’s like two Keiths. They’re both very similar. But Mick Taylor had something, the texture. Even now when I listen to the Stones’ channel on Sirius, I hear those Mick Taylor solos…Does something to me.

“In the beginning I had to re-think my whole life. I used to wake up in the morning and go to work from 9:30 in the morning to 7:30 at night. All of a sudden I’m with guys who wanted meetings at 11:00 at night. They were waking up at 3:00 in the afternoon. I came from a creative freedom. It was exactly the same. Now rather than focusing on a 12 album release, I was focused on one album, Sticky Fingers.”

With the arrival of the Sticky Fingers 2015 revenue stream model, I asked four Rolling Stones scholars about original Sticky Fingers vinyl pressings they cherished over fifty years ago.

(Poet) Dr. James Cushing: This was the first Stones studio LP created after the breakup of the Beatles, which is to say, after their favorite role-models became no longer immediately available. But I hear a funny White-Album vibe on Sticky Fingers, in the sense that each song represents a different genre. Take Side Two: it offers hard dance-rock, a slow Otis-type ballad, a Dylanesque folky thing (‘Sister Morphine’), a country-western number, and a string-infused Grand Gesture at the end. Five tunes, five genres -- and the mixup on Side One is just as surprising. Sticky Fingers was also the first-ever release on Rolling Stones Records, the one with the tongue -- and that fact makes the Beatles connection even more relevant, since the White Album was Apple's debut LP release in 1968. So, the Stones may have been looking for musical variety in their presentation, not simply sexiness.

“I think of Sticky Fingers as The Mick Taylor Album because his lead playing is so stellar throughout (except ‘Sister Morphine’ where it's Ry Cooder). His solos make the lesser songs like ‘Sway’ cohere, and he's at his absolute best on ‘Can't You Hear Me Knocking,’ another example of stealth-jazz at its best. I have Crusade, the Mayall Bluesbreakers LP Taylor did, and he plays very differently with the Stones.

“The Leeds live album (a very well recorded bootleg) [and now commercially out in 2015 with the new Sticky Fingers deluxe package], shows his playing brilliantly. As always, Charlie Watts wins MVP for driving the band as only a great drummer can… The concert occurred before the release of Sticky Fingers, so ‘Dead Flowers,’ ‘Bitch’ & ‘Brown Sugar’ are new to this audience -- these songs sound sloppy-fresh and fierce, and the band sounds more excited about playing them than the older songs (‘Honky Tonk Women’ sounds phoned-in -- however, ‘Midnight Rambler’ is longer and a lot more intense than on Ya-Yas, and Mick Taylor sounds especially heartbroken on ‘Love in Vain’).

“Jim Price, Bobby Keyes and Nicky Hopkins are auxiliary members, as they would be on the 1972 Exile tour, so the Stones are an eight-piece band here, pumping out a much richer, fuller soul sound than the Ya-Yas incarnation. I'm reminded of the Stax/Volt Norway TV taping, with Booker T & the MG’s with the Mar-Keys keeping it up behind Sam & Dave.

“A big question in rock seems to be: Are guitars sufficient? The answer seems to be, only at first. Think of all the bands that began with guitars-bass-drums and then added keys and/or horns as they ‘grew as musicians.’ The horns and piano here sound like an acknowledgement of the idea of The Soul Revue, which their 1972 Exile show certainly was.

“I bought The LP right when it came out, May 1971 at Discount Records in Westwood, and played it over & over as I was getting ready to graduate from bad old Harvard School… Rolling Stone Magazine gave it a mixed review.”

(Author) Kenneth Kubernik: I bought the album at Aaron’s Records on Melrose Avenue. Like Jordan Spieth on his run up to the Masters, the Stones were on a creative roll when Sticky Fingers surfaced in April, '71. Beggars, Bleed, Ya-Yas, they were running the table with the cutthroat gleam of white punks on some serious dope.

“The new album was an order of magnitude greater, a coruscating mosaic of all their variegated influences: alley cat blues, grand old country pickin', the nitro blast of rock 'n' roll and even a jigger of jazz (thank you, Charlie!). The songs, a libretto of salacious funk, celebrated a rogue's gallery of sexual buccaneers prowling and preying on the desperate and dissipated. It's a harrowing descent but performed with such jubilance, with such attention to musical detail (i.e. Paul Buckmaster's wall of strings enveloping Taylor's valiant, anguished leads and Hopkins' sanctifying triplets on "Sway"), that it startles and stirs in equal measure, like a pack of wolves baying at a luminous night.”

(Writer) Gary Pig Gold: At the time of Sticky Fingers, those Stones had reached another of their crucial career crossroads. New decade, new record company, new band. Almost. And as they most often did whenever push came to rough stuff (e.g.: "Jumpin' Jack Flash" and Beggars Banquet most recently) the band rose to the challenge with all five cylinders firing and all available fingers on deck.

"‘Brown Sugar’ in particular absolutely blasted apart the otherwise pretty damn milquetoasted Top 40 upon its Springtime '71 release, and the full album which followed opened up all new frontiers – and I'm not just speaking the front cover either – for the sturdy, stadium-ready mega-Stones to come. Thanks in no small part to Mick Taylor's brilliant work, Sticky Fingers displayed the band as slick, quick and nimble (albeit not as creative or groundbreaking as the Jones Stones), and this sheen served them very well until Ronnie Wood, aka Keith Jr. arrived to forever freeze the operation into its current state.

“Yes, the Santana-wanna second half of ‘Can't You Hear Me Knocking,’ not to mention Paul Buckmaster's ‘Moonlight Mile’ strings – the sort of uneasy-listening scores he would drench some of Elton John's best work with – sure paid off by bringing England's Oldest Surviving Hit Makers quite a big new audience, smack dab in the middle of the North American road.

"Still, the good ol' raunch 'n' roll remained nicely evident too (‘Bitch,’ anyone?!) and hat-tips to the band's country (‘Dead Flowers’) and blue-colored/collared (‘You Got To Move’ indeed) pedigree kept long-time listeners such as myself firmly rooted to the meat of the matter. Also, technical advances in the engineering dept. especially allowed Jimmy Miller to finally bring Wyman/Watts the punch and clarity they'd always deserved, to say the least, and while many commentators at the time professed concern with the drug-soaked nature of Sticky lyrically, at least Jagger was attempting to address matters more, um, frankly than Mungo Jerry or ‘Monkberry Moon Delight.’

"All in all, this is one of the extremely few early-seventies albums which can proudly stand with little or no tattered embarrassment forty-four long years and innumerable listens later. Not only that, but the front cover is still lots of fun to play with …unless, of course, you're stuck with the Spanish edition."

(Novelist) Daniel Weizmann: In the same way "Like a Rolling Stone" marked the spiritual launch of the Sixties, Sticky Fingers is the first rock album to have a totally seventies sensibility--decadent, insular, and cynical in a whole new way...the knowing, street-smart pessimism that would become common parlance for the oncoming decade.

“Over a year before Ziggy Stardust, they were already singing about satin shoes, plastic boots, cocaine eyes and speed-freak jive. Even the album cover vibes a comic sarcasm that is way ahead of its time -- packaged lust and zippers to nowhere. It could have been a punk album cover 8 years later. Part of this new tone--and part of the way the seventies came to define itself--comes from the burst bubble of counterculture dreams. ‘Love is the way they say is really strutting out,’ Mick sings on ‘Sway,’ but from his worn and torn bed of sorrow, he himself doesn't sound convinced. Brian Jones was dead, the Beatles were gone, the Utopian Decade was finished, and with Sticky Fingers, the Stones let you know they intended to survive, to ride out the moonlit mile without illusions.

“My older brother Moshe bought a copy of Sticky Fingers at Platterpuss Records on Sunset Boulevard. It seemed contraband, almost like a Playboy Mag or a ‘lid of grass’ -- like something you'd instinctively hide from your parents. At the time I couldn't figure out why, but now I get it. This was music against innocence.”

Harvey Kubernik is the author of 20 books, including 2009’s Canyon Of Dreams: The Magic And The Music Of Laurel Canyon and 2014’s Turn Up The Radio! Rock, Pop and Roll In Los Angeles 1956-1972. He has also written well-regarded books on Leonard Cohen, Neil Young, and 1967 The Complete Rock History of the Summer of Love.

Sterling/Barnes and Noble in 2018 published Harvey and Kenneth Kubernik’s The Story Of The Band: From Big Pink To The Last Waltz. In 2021 they wrote Jimi Hendrix: Voodoo Child for Sterling/Barnes and Noble.

Otherworld Cottage Industries in 2020 published Harvey’s Docs That Rock, Music That Matters.

His writings are in several book anthologies, including The Rolling Stone Book Of The Beats and Drinking With Bukowski.

On October 16, 2023, ACC ART BOOKS LTD published THE ROLLING STONES: ICONS. 312 pages. $75.00. Introduction is penned by Kubernik.