Killers of the Flower Moon (Soundtrack from the Apple Original Film) is the soundtrack album composed by guitarist/songwriter Robbie Robertson for the 2023 film Killers of the Flower Moon directed by Martin Scorsese. It was Robertson's final completed film score before he died in August 2023; the film is dedicated to his for his score, Robertson received a posthumous nomination for the Academy Award for Best Original Score in 2024.

Robbie Robertson's contributions to popular music have made him one of the most renowned songwriters and guitarists of his time. In Canada he was made an Officer of the Order of Canada.

In the 1960s, Robertson achieved worldwide fame and acclaim as a co-founder of The Band, laying a strong foundation for his broad range of five solo albums since the Band’s disbandment in 1976.

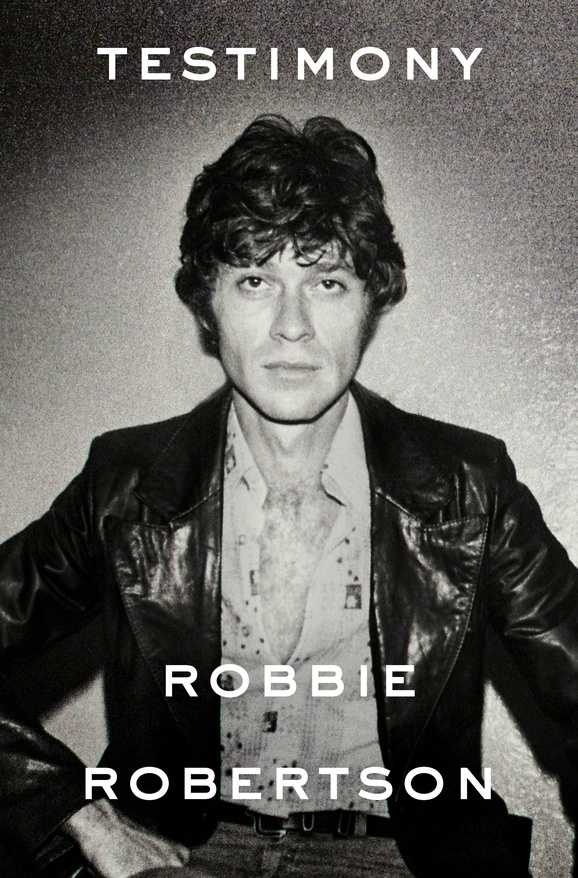

In his captivating insightful memoir, Testimony, published by Crown Archetype in November, 2016, written over five years of reflection, Robbie Robertson employs his unique storyteller’s voice to explore the trajectory that led him to some of the most pivotal moments in music history.

Robertson was born in Toronto, Ontario, in 1943. His book recounts the adventures of his half-Jewish, half-Mohawk upbringing on the Six Nations Indian Reserve and on the gritty streets of Toronto; his odyssey at 16 to the Mississippi Delta, the fountainhead of American music; the wild early years on the road with rockabilly legend Ronnie Hawkins and The Hawks; his unexpected ties to the Cosa Nostra underworld; the gripping trial-by-fire “going electric” with Bob Dylan on his 1966 world tour, and their ensuing celebrated collaborations; the formation of the Band and the forging of their unique sound, culminating with history's most famous farewell concert, brought to life for all time in director Martin Scorsese's acclaimed documentary and The Band’s timeless concert album, The Last Waltz, filmed and recorded in 1976.

With his very recent Oscar nomination, I felt it was appropriate to re-visit Robertson’s Testimony autobiography which captures time and place--the moment when rock 'n' roll became life, when legends like Buddy Holly and Bo Diddley crisscrossed the circuit of clubs and roadhouses from Texas to Toronto, and where Robbie met the Beatles, Jimi Hendrix, the Rolling Stones, and Andy Warhol.

Along the way Robertson encountered Sonny Boy Williamson, Conway Twitty, Roy Buchanan, Morris Levy, Otis Blackwell, Paul Butterfield, Mike Bloomfield, John Hammond, Otis Redding, Marlon Brando, the Crystals, Curtis Mayfield and the Impressions, Dion, Doc Pomus and Mort Shuman, Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller, Aaron Schroeder, and Charles Lloyd.

It's the story of exciting change as the world tumbled through the 1960s and early ‘70s and a generation came of age, built on music, love and freedom.

Robertson’s Testimony is a moving story of the profound friendship between five young men in The Band who together created a new kind of popular music.

Robbie’s autobiography is not a ghost-writer collaboration or an as told to memoir. This guy is blessed with a memory for details about the moments that not only informed his life but helped create songs and subsequent recordings that impacted our lives, too.

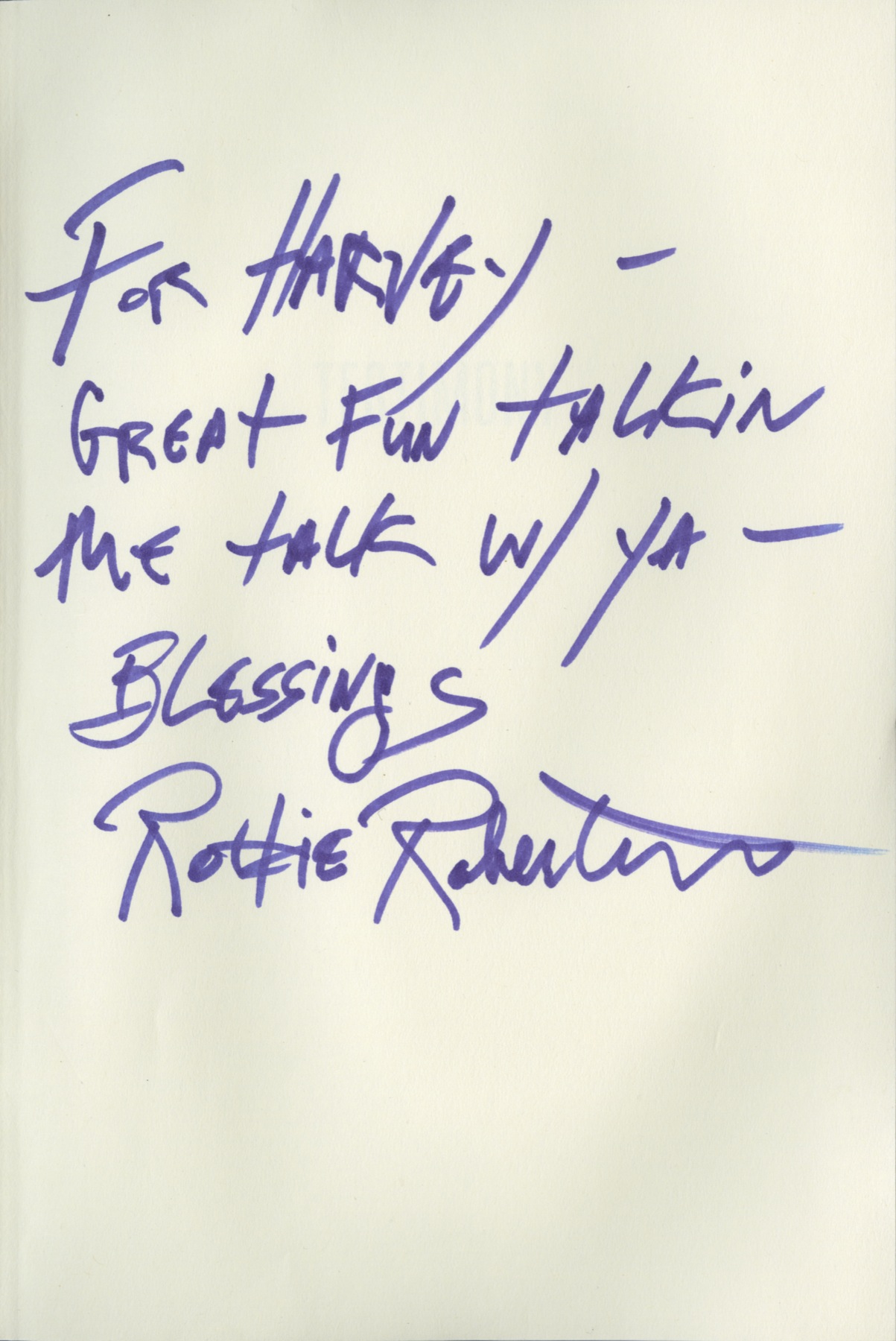

I first interviewed Robertson in 1975 for Crawdaddy magazine at Shangri-La studios in Malibu, California. In January 2017 I was invited to interview Robbie inside his office at The Village Recorders in Westwood, Ca. upstairs from where the Band and Bob Dylan recorded Planet Waves in 1973 with engineer Rob Fabroni and the live ’74 Bob Dylan and Band album Before the Flood was mixed. Sony Entertainment this year will be releasing a box set of 1974 Dylan/Band tour concerts.

Harvey Kubernik and Robbie Robertson Interview

(Portions of this interview were initially published in Record Collector News magazine print edition in their March 2017 issue).

HK: How and why did you decide to write an autobiography?

RR: I put it off and what has happened over the years there have been writers that have asked to write biographies on me. People who I really admired and liked. And I tried it three times with different people. And I felt, ‘this just doesn’t sound right.’ So, I would spend time and do interviews with them and they would go off and see if it works. They would go and write stuff and they would send it to me. And I thought, ‘God. It sounds like them trying to do an impersonation of my voice or something.’

“There’s something about this that just isn’t feeling authentic to me. And so I told the first guy I wasn’t going to be able to do this. And then, a couple of years later, another guy convinced me, and these are very reputable people. And I tried it again. And then a third guy but I shut that down before I got too far.

“Not because they aren’t gifted and everything, but what was becoming clearer and clearer was that I was gonna have to do the dirty work myself. And I knew that it was a lot of work. And, just to assume you can write a book is a luxury. I had done a couple of earlier books and they were warm ups. Not the same thing.

HK: There is so much more new information about yourself and The Band in the book and not in previous album liner notes, let alone interviews you’ve done the last 49 years, did you even read some other music memoirs as some sort of preparation for this endeavor?

RR: I purposely didn’t read these other books. One thing was that I didn’t want to be hindered or influenced or anything like that. But mainly because I don’t really like them very much if I can be completely honest about it. First of all, most of these people don’t actually write the book.

“So, I did read one book by a music person. Patti Smith’s Just Kids. And I thought that is terrific. The way that she writes. I thought that’s inspirational. That was like listening to a Jimi Hendrix record when he first came along. It was inspirationa1. I read the beginning of Chuck Berry’s book. Peter Guralnick told me I would like it. And Chuck actually wrote it. It was an authentic voice in it. And the fact that he started the book talking about the slave history in his family. I thought ‘Wow!’

“And Chuck Berry is very clear about wanting to write songs about people going to high school with life. So, Chuck said he was trying to write songs that young people would like. Getting up in the morning and going off to school. Cars and girls. It was like who would have thought Chuck Berry, first of all, would admit to something like that, and second of all, really thought that way. One of the kings.

HK: What was the pre-production before even formally doing this book adventure?

RR: I had to think of a structure. For some reason, and it could be from my film connection or something, but I had to find a structure that worked for me. I couldn’t say ‘OK. I was born…’ I’m already bored. So, I spent some time and I found a structure and said ‘Ah ha. There’s good story-telling there.’ And I could see it. Not only hear it but see it.

“So, I did that and I resorted heavily to going deep in my memory and using this vehicle, this gift supposedly that I have to the best of my ability. And the more I did it the more I liked it and the more it felt good. There were times and days where I said, ‘I hate this.’

HK: Did you type your thoughts on paper, typewriter or computer?

RR: I tried typing it on computer. I tried Dragon dictation. I tried everything and I ended up writing it long hand. And as I did it I thought ‘this is going to be around 400 pages, somewhere in that vicinity.’ And when I gave it to the publisher they said, ‘in book form this would be something like 840 pages.’ So I thought ‘I didn’t know what I was doing.’ So I had to do some cutting. There were a lot more stories and a lot more detail in it. Then I went to work in cutting it down to 500 pages.

HK: Was your book always going to be in a straight chronological order? It does unfold year by year.

RR: I wanted to do the structure thing like I said in the beginning where I start with the musical journey. I start with that. Then I can go back and talk about what got me to this place. I could do that. And after a while I’m on this train. I’m on this path and then I’m talking about another path that goes along parallel and that goes along side of it. And one catches up with the other one. And then they become one after a while. So that was the way. And I didn’t want it to be scattered. I wasn’t trying to do this to make it confusing. I was doing this to help the story right. Once I got up to a certain point and these two parallels came together then I was kind of off and running.

HK: Was there a point in the writing process where you stopped and reviewed the data and showed the results to your publisher or friends for feedback or encouragement? Or was that done in the editing process?

RR: Well, there was a point when I thought, you know, I don’t want to be doing something and it doesn’t work. (laughs). And I was getting so inside of it that I wanted to share it with the publishing company, the editor. And so at some point I gave them nine chapters.

“The first step was to do a chapter and then it would get transcribed and I’d work on it. Jered Levine [manager] was a great soundboard in this thing. Once in a while he’d ask me to expand it. ‘I don’t understand this.’ Because sometimes you get lost in your own world. Right? You know, that you’re writing and you think everybody understands because I understand so everybody else understands it. And Jered would offer, ‘I don’t think this is clear.’

HK: I want to ask about photo selections. I know you were very active in this visual aspect. I saw some photos of The Band I had never seen, and obviously, your own family pictures.

RR: The cover photo I had never seen before. They found that photo. The pictures in the book are part of the story. There were other pictures we looked at but they were not part of the story. So, I think for the inside pictures probably 80-90 per cent of them, the early stuff, come from my family’s archive. And a lot of The Band stuff was from Elliot [Landy].

HK: Did you ever think over the last few decades when remembering things, ‘I’ve got to write a book someday’

RR: I never thought like that. I didn’t think about it until I went there. But over the years to friends, I told some of these stories and when I told them the story they would be like ‘Holy shit!’ So, I would be like, ‘I guess that’s interesting to somebody.’ Like when I talk about the Jack Ruby experience in Dallas, Texas. It’s like I told people about playing that Skyline Lounge club before.

“So, these stories got so heavy from carrying them around all these years that when I got to this place I thought ‘I can’t carry them all anymore. It’s too much.’ And writing this book I felt like ‘I can unload this.’ I feel lighter. I feel like now I don’t have to tell these stories anymore. I can hand you the book. (laughs). But it also brings me to a place where…I wrote an autobiography that ends when I’m 33 years old. Right? So, the publisher people are saying ‘you can’t write your life story and end at 33.’ Now what?

“So now I’m thinking about volume 2. And there could be volume 3. It might be a trilogy for me to be able to go to each of these places and be able to gather all the story-telling and all the colors that fit into that period.

HK: After completing the book, what did you learn about yourself? The physically departed are always with you in the present.

RR: But also, one of the big differences from the point of view I was writing from, I’m not writing from now looking back. I’m writing about when it’s happening. So the surprises are there and I don’t know what’s coming next. And so from that point of view I can only be present in that time. In that period. None of it is from ‘why I remember back when…’ No. No. I didn’t want to do that. I have to go to that place and be in that room to tell that story.

HK: You began the book visiting the Brill Building with Ronnie Hawkins to the office of Morris Levy, owner of Roulette Records. You wonderfully described his receptionist “as a cross between Veronica Lake and Joi Lansing.”

RR: Yeah! Thank you.

HK: And after this seminal experience you circle into family history. Did you think you needed the rock ‘n’ roll epicenter or this device at the start to establish a path before pivoting into your upbringing in Canada?

RR: What I wanted to do was I wanted to start with music. But not that I was dipping my toe in the water. I wanted to start where the mission began. And the mission began when I took a train from Canada down to Arkansas. As I call it in the book, ‘to the fountainhead of rock ‘n’ roll.’

“Riding on that train going down there and the feeling that that gave me at age 16 was so pivotal, was so deep in my overall journey. In my whole experience that I thought, ‘That’s where I’ll begin.’ And then I’ll do these flashbacks to what got me to the train.

HK: In reading Testimony I never knew how much time you spent at the Brill Building meeting all the legendary songwriting teams. Leiber and Stoller, Pomus and Shuman, Henry Glover and the music publisher Aaron Schroeder.

And now when I listen to some of the Band recordings, I know you learned things about songwriting, arrangements and voicings from these visits. I realize your Band songs were longer than 2:45. But your tunes were initially covered, not by girl groups, but girls like Jackie DeShannon, Aretha Franklin, Dionne Warwick, and Joan Baez, as well as recording artists that spotlighted female singers: the Staple Singers and Rotary Connection.

RR: You are onto something. Oh yeah. One of the things that I really took away from that was Doc Pomus and Mort Shuman or Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller, or Otis Blackwell, and a thing I had to cut out with [blues singer and songwriter] Titus Turner, who was an incredible character.

“Anyway, one of the things I really got from them, because the obvious thing was that they tapped into something that felt good. But it had to feel good. The song could be about anything but it had to feel good. And I was like. ‘Wow…’ It would be one of the guys sitting at the piano playing. ‘Let me think of something. What about this?’ And they would start to play something. I was studying. I didn’t know what the song was about but it feels good. So I just thought coming in that door, coming in the back door of something, that when you start this thing if it doesn’t feel good then stop right now. ‘Ah ha. That’s something.’

“Then, the other door was Bob Dylan. Who it wasn’t about that. It was about emotion and an energy. But it was really about saying something. It wasn’t about ‘these words could be anything.’ No. No. It was specific. So to me it was rebelling in a beautiful way against this other thing.

HK: With the exception of music publisher, Lou Levy of Leeds Music, the Brill Building wasn’t very receptive to Bob Dylan when he was first hawking tunes. Leiber and Stoller allegedly couldn’t comprehend it.

RR: I know he has said something about that.

HK: But you wrote songs on guitar and most of songwriters were lyricists and piano players.

RR: Neil Diamond played guitar. And I later produced an album on him.

“I thought who would think in their wildest imagination that Tin Pan Alley was a real place. The Brill Building. And then Donnie Kirshner’s thing. All of it was actually in a place you could go. And the doors were golden when you walked in. And inside there in all these rooms were people who wrote songs and sent them out to the whole wide world.

HK: Your book points out that some Brill Building mainstays remained friends of yours for years, and saw your success with The Band. I thought the Brill Building was just a brief pit stop for you and Ronnie Hawkins when you wrote and played on a few of his records. But the impact and connections continued.

RR: I had such a respect and a connection feeling for these people. And I knew Doc and Mort. Doc and Mort remained friends. And I recorded with John Hammond, Jr. on an album that Leiber and Stoller produced. I was friends with Jerry and Mike. So, to say none of that rubbed off on me just wouldn’t be true.

HK: Do you think the Brill Building taught you how to write for specific voices like Levon Helm, Rick Danko and Richard Manuel who would later be in The Band with you?

RR: I wasn’t the lead singer in The Band. I don’t know if the Brill Building influence was that specific on arrangements and voices but I did try and soak up as much as I possibly could from the guys.

“So, to say none of that rubbed off on me just wouldn’t be true. And it was stuff that I don’t know that if you grasp it on the surface but in a way of seeing the way these guys could adapt to these different artists. And they could write something and then cast it. Or, someone could say, ‘we need this. We’re coming to you.’ And they could write for that. And I thought that was a special gift. And I was doing that in the Band.

“I thought my job was in this was what they were doing too. My job was to say, ‘I’m going to write a song that Richard Manuel could sing the hell out of. I know what to do with his instrument.’ And so the answer is, in some subliminal way, absolutely yes.

HK: Did you learn that the song was king inside the Brill Building as opposed to the sound?

RR: I thought the sound was really important to me too. It still is. My first attraction to rock ‘n’ roll was just as much the sound was the song and the song was the sound. So when I heard these early Sun and Chess Records, I thought, ‘what is going on here?’ Before that Les Paul and Mary Ford in his New Jersey home studio. This sound thing. Because records before that you didn’t think that much about the sound. It was a vocalist and some music in the background.

“When rock ‘n’ roll came along there was coming out of these different studios from places in Texas, Memphis and New Orleans. The sound of the records coming out of New Orleans that was [engineer and studio owner] Cosimo [Matassa]. What is going on here? The sound coming out of Chess Records in Chicago. I thought ‘what kind of a room is that? What is this magic?’

Harvey Kubernik is the author of 20 books, including 2009’s Canyon Of Dreams: The Magic And The Music Of Laurel Canyon and 2014’s Turn Up The Radio! Rock, Pop and Roll In Los Angeles 1956-1972. He has also written well-regarded books on Leonard Cohen, Neil Young, and 1967 The Complete Rock History of the Summer of Love.

Sterling/Barnes and Noble in 2018 published Harvey and Kenneth Kubernik’s The Story Of The Band: From Big Pink To The Last Waltz. In 2021 they wrote Jimi Hendrix: Voodoo Child for Sterling/Barnes and Noble.

Otherworld Cottage Industries in 2020 published Harvey’s Docs That Rock, Music That Matters.

His writings are in several book anthologies, including The Rolling Stone Book Of The Beats and Drinking With Bukowski.

On October 16, 2023, ACC ART BOOKS LTD published THE ROLLING STONES: ICONS. 312 pages. $75.00. Introduction is penned by Kubernik.