I saw The Band in concert 8 times, including three Bob Dylan/Band Inglewood Forum shows on the 1974 tour, and attended The Last Waltz. In January 2017 I was invited to interview Robbie Robertson inside his office at The Village Recorders in Westwood, California, upstairs from where the Band and Bob Dylan recorded Planet Waves in 1973 with engineer Rob Fabroni and the live ’74 Bob Dylan and Band album Before the Flood was mixed.

Harvey Kubernik and Robbie Robertson Interview:

(Portions of this interview were first published in Record Collector News magazine in their March 2017 issue).

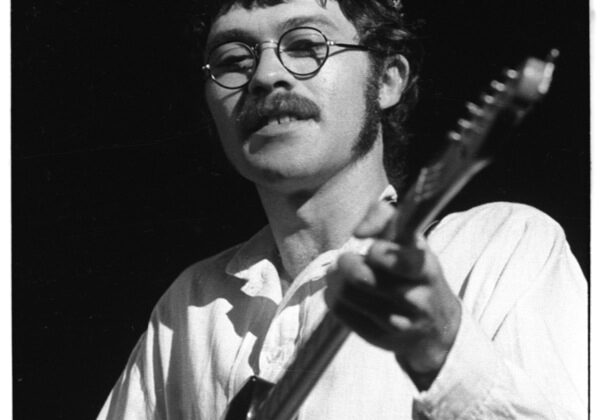

Photo by Henry Diltz, Courtesy of Gary Strobl at the Diltz Archive.

HK: Before you cut Music From Big Pink you recorded The Basement Tapes with Bob Dylan. Many of those sessions yielded cover versions before they were officially released a couple of years ago. Leon Russell told me he made solo albums “so significant artists will cover my tunes.”

RR: Yeah. I knew that about Leon. But we did have the experience with Bob Dylan and in doing The Basement Tapes with the songs that were supposed to be shared with other artists to record. It was because so many people recorded Bob’s songs and we were hooked up together, you thought "Oh. That’s part of it." And how that struck me; I didn’t think about it in writing the songs or making the records that other people would do. This was a very interior thing. This was a thing between the five of us in the band. Something that we had collected over ages and pulled it together and made this gumbo.

HK: I never knew that you were the guy who assembled the initial or original 14 song acetate demo that was serviced to music publishers. Then recording artists like Manfred Mann did “The Mighty Quinn” and Brian Auger, Julie Driscoll and the Trinity recorded "This Wheel’s On Fire." I know Peter, Paul & Mary were first with “Too Much of Nothing.” Bob Dylan must have had hundreds of cover versions before this acetate was circulated. Did you think these songs had such durability?

RR: No. But Bob already had such a track record that you thought people are going to be drawn to this. If he put something out there for people to record, people are going to be drawn to this. It just seemed to me that this was something he’s already established. So, it wasn’t after we sent out these songs and everything, and it wasn’t me saying this is exactly what it was.

Bob was involved in it. Garth was involved in it. Right? And part of it was just in fun. You know, we would record a song like "You Ain’t Going Nowhere." And Bob would say. "Whatta you think? Ferlin Husky? Right?" And it was half kidding around and half meaning somebody is going to, but with the way that he is and the way that he thinks, too, Bob could insist on sending that song to Ferlin Husky first. You know what I mean? Just because he would do something like that. But when we said "OK." We’ve got to pull some of these things. We were recording a lot of stuff. We were covering songs and just having fun. And then every once in a while there would be an original one in all of this.

And when we were doing this not with Bob, this was the germs and the idea and the beginning of Music From Big Pink. That was happening kind of in the back room, too. So, when we chose those songs to send out we were choosing what we liked. We were kidding around. I didn’t notice Manfred Mann could do a really great job on "The Mighty Quinn." I didn’t know that. But we were saying that "The Mighty Quinn" thing has something to it. It really was what felt right in putting that collection together.

HK: Who knew when I first heard Music From Big Pink that you guys logged many years playing together. At least a half a decade before we heard the Band on LP.

The time period reminds me of former professional baseball player, Maury Wills of the Los Angeles Dodgers. He spent 8 years in the minor leagues before he got to a major league team. Very early on he wins MVP of the National League and the Dodgers win the World Series his first year with the squad in 1959. Musicians paid dues then.

RR: But I started in that thinking of becoming a veteran when I was age 16. And so by the time we had done the thing with Ronnie Hawkins, done the thing with the Hawks, played with Bob Dylan, I’m still 22. Right? And when I’m writing Music From Big Pink I was 23. Right? It’s because of starting so early, you know. And Levon was a few years older than me. And Garth several years older than me. But Rick and Richard were right around the same age as me. When they came into the Hawks they were 17 years old. I was 16. But they looked at it as "How do we do this?" They looked at it like I was a teacher already.

HK: The Band’s Music From Big Pink blew a lot of minds. Your book reinforces the fact that a decade before this LP was released, you and group members always wanted to do albums and be a band. Your debut LP was not really an outgrowth from road work with Bob Dylan. You had logged some time in recording studios. Yet, everyone from your manager, Albert Grossman, Al Kooper and Bob Dylan himself, were very thrilled and really super-impressed when they first heard the album acetate on playback at Albert’s house.

RR: When we hooked up with Bob Dylan it was made clear to Bob and to Albert ‘this is a whistle stop for us.’ We are on our own path. We’ll do this in the meantime but we’re going to do our own thing. We’re not here. We’re here to do this. Right?

After we did the thing with Bob and he wanted to do more. But he had this accident and so then, and I say this in the book, Albert had no idea what we were or what we could do. No idea. He liked us. He thought it was really interesting what we did with Bob. But he said ‘I think I can get you a deal for doing an album of instrumentals of Bob Dylan songs.’ So I said, ‘All right. Let me talk to the guys about that.’ (laughs). And I thought, ‘Albert has no idea.’

When we recorded Music From Big Pink Albert was astonished by the results of that record. And he so embraced it and made it his own and all that other stuff vanished. He was like ‘I knew it all along.’ It fit so perfectly into his scenario.

Bob and the Band were so close to Albert. We had been through everything together. Like I say in the book, we were like war buddies. And we had gone to the edge together. And because we had done all that stuff and The Basement Tapes, and through all of this, still had no idea of what this was going to be when we did it. That was thrilling.

HK: The Band did some recording for Music of Big Pink at Gold Star studios in East Hollywood after your label Capitol let you check out another studio down the street. 2005’s The Band: A Musical History contains a couple of recordings from those sessions.

In the 2003 expanded and remastered “Music From Big Pink” Band album, some of the new “bonus” tracks, include Jimmy Drew’s “Baby Lou," and an abridged rendition of Dylan’s “Long Distance Operator,” while the full version of “Long Distance Call” appears on The Band: A Musical History.

RR: We were doing some recording at the studio at Capitol Records in Hollywood and it was one thing, but there was such talk about just ‘the vibe’ and ‘the sound’ at this other place, Gold Star.

We were kind of off the clock, and we were going to record some things that weren’t necessary going to be on the record, so we thought, ‘let’s just go and check it out.’ I think we were only there one day or two days. And there are two other tracks that we did there that I don’t know what’s become of those.

HK: The Basement Tapes and The Band album were recorded inside Sammy Davis, Jr.’s pool house in the Hollywood Hills. In a way you started low-fi recording when a music group on a major label moved into a home studio and did masters for albums not just recorded demos.

RR: That’s where that Les Paul thing came back into the picture. Before Big Pink, I had had this dream of having a workshop. A place. A sanctuary where we could go into the privacy of our own world and do something and not be on somebody else’s lawn to really be in our own environment let alone away from studio union breaks, so all of these things played into it a little bit. We go into a studio and the guy is like "Well, it’s almost 4:00 pm…" So all of these things are playing into it and although the experience in the studio of recording Music From Big Pink was fabulous.

The producer John Simon was great and the engineers were great at Phil Ramone’s place, all of it, but the idea of having this private sanctuary and that it would have its own sound. Its own sound and its own flavor.

It would be like Chess. We could have our own one. And it would not sound like any of these other places. Going into somebody’s environment and then saying, ‘you go over there. You sit here. And we’re gonna use this kind of microphone on you.’ I thought that was what you did with somebody else. ‘I feel like I’m getting seconds here.’

I was thankful for that period of time too. Because it was now a period where an artist wanted to something that A&R guys like [Capitol Records engineer and staff producer] John Palladino had nothing to do with the music. He was never there when we recorded. No intrusion.

So I said ‘we want to do this thing that started in the basement of Big Pink, we want to bring the equipment to us in our own atmosphere. And we want to record at whatever time we feel the spirit. We don’t want to be on somebody’s clock. John was like ‘OK. ‘We just need the equipment to come to us.’ And he had to kind of go along with it, you know, but he didn’t understand it.

We then did Stage Fright at the Woodstock Playhouse and brought the equipment into that room. But it’s very common today.

When I went to Dublin, Ireland to do some experimenting with U2, they were recording in the living room of Adam [Clayton’s] house, and when I walked in, the producer Daniel Lanois, Edge and Bono said, ‘Does this feel familiar?’ And I didn’t quite understand what they meant. What they were saying was ‘you are the guys who started this whole thing.’

HK: You assembled a new compilation CD also called Testimony. There are some solo selections like “Unbound” and “Somewhere Down the Crazy River,” a track from Dylan’s Blonde On Blonde, where you played guitar on the “Obviously Five Believers” session, and a handful of live recordings of the Band, and Bob Dylan & the Band.

RR: The CD is a journey. It was really trying to look at that horizon and see what did the sun shine down on this horizon.

The song ‘Testimony’ [title track] came along after but it’s the name of the book. That’s the only reason it got in there. And then try and find some things of worth that weren’t the obvious. There’s a song I wrote with Rick. I only wrote a couple of songs with Rick. Like ‘Bessie Smith.’ It was a wonderful experience and I didn’t do a lot of that with Rick it was kind of special. And another one, ‘Home Cookin’.

And the CD combines studio and live recordings. We were gathering this stuff, too. Jered had very specific thoughts on it. I thought that’s cool, too. ‘Cause it’s not all from the period that the book takes place. ‘Out Of The Blue’ is in there, too. I thought, ‘Wow. We’re breaking a rule here. That’s good.’ Plus ‘I’m Gonna Play The Honky Tonks,’ a Bobby ‘Blue’ Bland track that Richard sang with Levon and the Hawks. It was in the club set list.

I had just written a song called ‘Twilight’ on the piano. And, like I always did, I would then play it for the other guys and say, ‘I’ve got a new one. See what you think.’ And because I played it for them in the studio at Shangri-La, sitting at the piano, because I was sitting there and I knew how to do it, but you don’t often see that. What’s not on there is ‘Hey guys I have a new one.’

It’s me playing the song, even getting the lyric wrong in one place but because I didn’t have them written down because I was remembering them. But anyway, it was one of those moments, you know, that you don’t have a lot of. Because usually when I played them a song we would be at somebody’s house. We wouldn’t be in the studio. ‘Cause we had just recorded something.

HK: I’ve always wanted to know why the Band and Bob Dylan selected the Village studio in West Los Angeles to record Planet Waves and mix the 1974 live Before the Flood album. Were the group members living near the Pacific Ocean as early as 1973 or ’74?

RR: There weren’t many studios in this side of town. And when I came out from Woodstock and New York to the West Coast, and I write about it in the book too, that David Geffen convinced me to go to Malibu. At the time I don’t know if I had ever been to Malibu. You know what I mean? We might have driven down there in an afternoon or something, but I didn’t know what Malibu was. So it just shows you how good David was in convincing me of something.

Anyway, it was all west side. And Village was the only studio. And it was new. And my current room, my office, was studio C. The first room in the building. Where people recorded. And tons of people made records in this room. When I came along I took over this room. That’s why the office has this big window. Because it was the actual studio. Then they built studio B. I don’t know why they started with a studio C. Maybe [George] Geordie Hormel [original owner] thought ‘Oh. I’m gonna add and do stuff.’ Then the next room was B, and then studio A. And then studio D. And now there is other stuff upstairs.

So the fact that it was on the west side was rule number one. Rob Fabroni was already here. When you came here to record he was the engineer who came with it. And Rob was terrific. I’ve done a ton of stuff here on the west side. It’s a West Side Story. [laughs]

HK: Last year Columbia Records and Legacy Recordings issued Bob Dylan: The 1966 Live Recordings, a 36 CD box of your joint 1966 concert tours of the U.S., U.K., Europe and Australia. Your guitar playing is all over the dates.

When we talked in 1976 about the Band reuniting with Dylan on the 1974 tour, you remarked “at least this past time we weren’t booed,” referring to nights on the Dylan/Hawks 1966 tour.

In Testimony there is a great line about the 1974 tour where you wrote “we fought a good battle in ’66, but we won the war in ’74.”

I have a hard time comprehending Dylan and your group being booed on the world tour of 1966. What I remember about the 1974 shows I saw, everyone was totally digging the blend on stage.

RR: There was a thing that happened between Bob and the Band on stage when we played together that we would just go into a certain gear automatically. It was like instinctual, like you smelled something in the air, you know, and it made you hungry. (laughs). It was that instinctual. And the way we played music together was very much that way. And whether we were playing in 1966, or 1976, or when we did the tour together in 1974, we would go to a certain place where we just pulled the trigger.

It was like ‘just burn down the doors ‘cause we’re coming through.’ And it was a whole other place that we played when we weren’t playing with him. So it was like putting a flame and oil together, or something. I don’t know.

When we did the Dylan and Band tour in ’74, where we went and did a lot of the same things we did back in ’66, and the people's response was ‘this is the shit and I knew it all along.’ It was like you weren’t really there all along. It’s interesting and it’s one of the things I talked about in my keynote speech that I made [last decade] at the SXSW conference.

It’s really a very interesting experiment to see, or go from something that people were so adamantly against this music, and that we didn’t change nothing, and the world revolved, and everybody came around and said ‘this is brilliant.’ That was very interesting to see everything else change around you.

Well, we didn’t change. [laughs]. I don’t know that this has ever happened to anybody else. And it is a phenomenon. And that’s why I feel bold enough to refer to it as a musical revolution. Because the world came around. We didn’t. We didn’t do anything that much different. [laughs]. We just went out there and hit it between the eyes. And now people have a completely different reaction to it. And I thought ‘that’s kind of incredible that the world actually came to this place,’ you know? And I don’t know who else has been through that.

HK: Last December, Rhino Records released The Last Waltz celebrating the 40th anniversary. Did you have interaction with Bob Dylan before the show regarding your repertoire?

RR: Oh, for sure. We threw our thoughts into the hat and then we would try stuff, and if it felt right, then we just did it. It was one of those things like letting some higher power make the decision, because the proof was in the pudding. And ‘let’s play that song and see how it feels.’ We would that and say, ‘that was fun. Let’s do that.'

But Bob wanted to do stuff that was connected with our origins together, which is why we did ‘Baby Let Me Follow You Down,’ which we played back then, and ‘I Don’t Believe You (She Acts Like We Never Had Met).’ And having a thread going back to 1965-1966. And, because it felt real. And obviously ‘Hazel’ and ‘Forever Young,’ because us working together on the Planet Waves thing. So, it was trying to find a connection, and not just do something that nothing to do with anything. We wanted it to have some thought. Nobody suggested ‘Hazel,’ but Bob said I think we should do ‘Hazel.’

We had to make sacrifices originally, obviously, in the movie, because it’s a movie, and you have to edit a movie so it plays. But on the record we had a limited amount of space, too. And I was always taken by Bob’s performance on ‘Hazel.’ I thought he did an amazing performance on it and poured such passion into this song.

Out of all of the songs we can do together what do you think we should do?’ It was like we’ll do some of the stuff from the 1965-1966 period. We’ll do something from Planet Waves, we had just recorded it a couple years earlier. And in mixing it up we ran through a bunch of crazy ideas, too. Like Bob said ‘should we do a Johnny Cash song?’ And he would start singing a Johnny song and we all knew this was never gonna fly. But it would be fun to play it. We’d play through it and say. ‘No.’ But all of this stuff, it was really like throwing things up in the air and see where they would fall. But Bob said, ‘you know one song I think we should do is ‘Hazel.’ We were like ‘Really? OK. Let’s do it.’ And we ran through it and it felt pretty good. ‘All right.’ But we knew we wanted to do ‘Forever Young.’ Because it connected to the occasion with all the people there and this generation and all of this stuff. Like Dr. John singing ‘Such a Night.’” •

• HARVEY KUBERNIK is the author of 20 books, including 2009’s Canyon Of Dreams: The Magic And The Music Of Laurel Canyon and 2014’s Turn Up The Radio! Rock, Pop and Roll In Los Angeles 1956-1972.

Sterling/Barnes and Noble in 2018 published Harvey and Kenneth Kubernik’s The Story Of The Band: From Big Pink To The Last Waltz. In2021 they wrote Jimi Hendrix: Voodoo Child for Sterling/Barnes and Noble. For 2024, the duo is working on a book with rock music photographer Ed Caraeff to be published by Insight Editions.

Otherworld Cottage Industries in 2020 published Harvey’s Docs That Rock, Music That Matters.

On October 16, 2023, ACC ART BOOKS LTD is publishing THE ROLLING STONES: ICONS. 312 pages. $75.00. Introduction is penned by Harvey Kubernik. Spanning six heady decades, and countless tours and album covers, this thrilling portfolio features imagery from some of the most eminent names in photography, alongside the photographers’ own memories and reflections. Includes photographs by Terry O’Neill, Gered Mankowitz, Linda McCartney, Ed Caraeff, Ken Regan, Douglas Kirkland, Dominque Tarle and founding member, bassist and photographer, Bill Wyman. Each photographer has selected images for their chapter and written an introductory text about their time working with the band

Harvey Kubernik’s writings are in several book anthologies. Most notably, The Rolling Stone Book Of The Beats and Drinking With Bukowski. Harvey wrote the liner notes to the CD re-releases of Carole King’s Tapestry, The Essential Carole King, Allen Ginsberg’s Kaddish, Elvis Presley The ’68 Comeback Special, The Ramones’ End of the Century and Big Brother & the Holding Company Captured Live at The Monterey International Pop Festival.

During 2006 Kubernik spoke at the special hearings initiated by The Library of Congress held in Hollywood, California, discussing archiving practices and audiotape preservation.

In 2017 Harvey appeared at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland, Ohio, as part of their Distinguished Speakers Series.

During 2023, Harvey Kubernik, photographer Henry Diltz and authors Eddie Fiegel, Barney Hoskyns and Chris Campion were filmed by French director France Swimberge for her Mamas & Papas documentary. Broadcast scheduled on the European arts television channel, Arte. Kubernik is the consultant for the film.

Kubernik was an on-screen interview subject for director Matt O’Casey in 2019 on his BBC4-TV digital arts channel Christine McVie, Fleetwood Mac’s Songbird. The cast includes Christine McVie, Stan Webb of Chicken Shack, Mick Fleetwood, Stevie Nicks, John McVie, Christine’s family members, Heart’s Nancy Wilson, Mike Campbell, and Neil Finn.

Harvey was lensed for the 2013 BBC-TV documentary on Bobby Womack Across 110th Street, directed by James Meycock. Bobby Womack, Ronnie Wood from the Rolling Stones, Regina Womack, Damon Albarn of Blur/the Gorillaz, and Antonio Vargas are spotlighted.

Kubernik served as Consulting Producer on the 2010 singer-songwriter documentary, Troubadours: Carole King/James Taylor & the Rise of the Singer-Songwriter, directed by Morgan Neville. The film was accepted at the 2011 Sundance Film Festival in the documentary category and PBS-TV broadcast the movie in their acclaimed American Masters series. Harvey was also a featured talking head in director Matthew O’Casey’s 2012 Queen at 40 documentary broadcast on BBC Television and released as a Blu-Ray DVD, Queen: Days Of Our Lives in 2014 via Eagle Rock Entertainment).