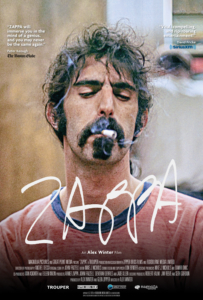

ZAPPA, the first all-access documentary on the life and times of Frank Zappa was set to premiere at the 2020 SXSW film festival. The Kickstarter campaign for this project was the highest funded documentary in crowdfunding history.

ZAPPA was acquired by Magnolia Pictures in August and will be released day and date on November 27, 2020 in the U.S. Produced by Alex Winter and Glen Zipper. ZAPPA, a film by Alex Winter, is a Magnolia Pictures and Great Point Media and Trouper Production in association with Zipper Bros Films and Roxbourne Media Limited.

With unfettered access to the Zappa family trust and all archival footage, ZAPPA explores the private life behind the mammoth musical career that never shied away from the political turbulence of its time.

Alex Winter’s assembly features appearances by Frank’s widow Gail Zappa and several of Frank’s musical collaborators including Mike Keneally, Ian Underwood, Steve Vai, Pamela Des Barres, Bunk Gardner, David Harrington, Scott Thunes, Ruth Underwood, Ray White and others. Ahmet Zappa is a producer on the film.

A soundtrack album to ZAPPA will be released by Zappa Records/Ume label during November.

Alex Winter was born in the United Kingdom. He’s a child actor who entered show business with co-starring Broadway roles in The King & I and Peter Pan. Alex is a graduate of the Tisch School of the Arts at New York University where he was a film major and a photo minor.

Winter is also known for portraying Marko in the vampire movie The Lost Boys.

Winter subsequently founded Trouper Productions, a company that supports his films. In 2019 Winter released two new documentary feature films; The Panama Papers, about the biggest global corruption scandal in history and the journalists who worked in secret and at great risk to break the story and is out now on Hulu, Amazon Prime and Epix in the US. Trust Machine: The Story Of Blockchain, about the rise of bitcoin and the blockchain was released last Fall and is now available on Amazon Prime.

Previous documentary work includes Deep Web, about the online black market Silk Road, and the trial of its creator Ross Ulbricht. The film premiered on the Epix network, opening as the #1 documentary on iTunes and earning a Cinema Eye nomination among several award wins. Deep Web is now available for streaming and VOD. Downloaded is a VH1 RockDoc about Napster and the digital revolution.

Winter’s Showbiz Kids documentary feature for HBO premiered July 14th on the network and is now available through HBO GO, HBO NOW, and on HBO via HBO Max and other partners’ platforms.

The third installment in the Bill & Ted franchise, Bill & Ted Face The Music is now available in theaters and on demand in the U.S. and is continuing to roll out internationally this year.

“It seemed striking to me and producer Glen Zipper that there had yet to be a definitive, all-access documentary on the life and times of Frank Zappa,” explained Winter in the publicity materials provided by Magnolia Pictures.

“We set out to make that film, to tell a story that is not a music doc, or a conventional biopic, but the dramatic saga of a great American artist and thinker; a film that would set out to convey the scope of Zappa’s prodigious and varied creative output, and the breadth of his extraordinary personal and political life. First and foremost, I wanted to make a very human, universal cinematic experience about an extraordinary individual. What helped make this vision possible was Gail Zappa granting us exclusive access to Zappa’s vault; a vast collection of his unreleased music, movies, incomplete projects, unseen interviews and unheard concert recordings. With this wealth of material, and the minimal addition of present-day interviews with Frank’s closest friends and musical collaborators, we built a narrative that is both intimate and epic in scope.

“But before we could set about making the film, we needed to preserve a great deal of material from the vault that was deteriorating and in great danger of being lost forever. So we created a crowdfunding campaign, and were lucky to break funding records for a documentary related project. And thus began an exhaustive, two year mission to preserve and archive the vault materials. When this was completed, we set about making the film.

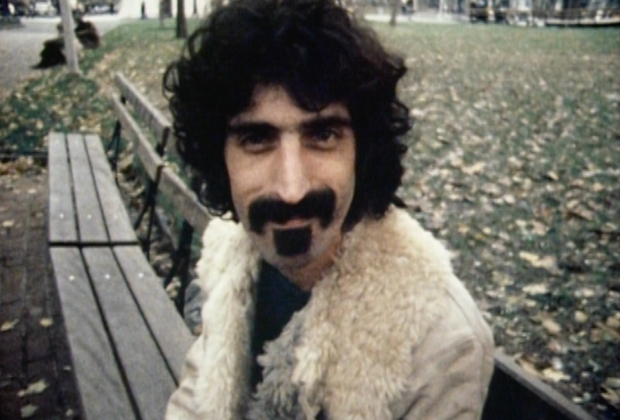

ZAPPA - Courtesy of Magnolia Pictures

“Ultimately, ZAPPA is not a retro trip into the past, but a thoroughly modern exploration of a man whose worldview, art and politics were far ahead of their time, and profoundly relevant in our challenging times.”

I witnessed Frank Zappa at a 1968 Pinnacle dance concert in downtown Los Angeles at the Shrine Exposition Hall, touted his work yearly in the seventies for Melody Maker, and met eventually Frank in 1985.

After viewing a screening of this marvelous and revealing ZAPPA documentary, I asked a few literary and music associates this century, who are avid Zappa fans, some worked with him, to comment on ZAPPA as well as reflect on this genius who resided in Laurel Canyon and his monumental artistic legacy.

“The debut solo album by Frank Zappa, the original Lumpy Gravy Verve LP was & remains unlike any half-hour of musical sound ever marketed as ‘rock,’ miles beyond what Brian Wilson or Lennon-McCartney or Syd Barrett were thinking up,” poses Dr. James Cushing.

“The juxtaposition of the precise orchestral passages with the deranged ‘pigs & ponies’ spoken word bits suggests an epic, God's-eye-view of American culture in all its promise and tawdriness, all its integrity and craziness. (There's another suggestion: the integrity may be inseparable from the craziness.)

“Personally, Lumpy Gravy will always represent the secret surrealism of the San Fernando Valley, especially Ventura Blvd between Sepulveda and Laurel Canyon (Encino, Van Nuys, Sherman Oaks, Studio City, North Hollywood). Zappa's music provided me with a spirit-map of the area when I first moved here in 1967, and continued to do so with the next few albums.

“Is it better to have a dream (in the sense of an unrealized goal in the future) or to realize it (in the sense of gratifying a desire in the present)? I think the gratification is better because it leads to further desires, but to have a dream risks being personally frustrated or warped if it doesn’t pan out — the Jay Gatsby problem.

“As a Zappa fan since 1967, I saw things in this new documentary that I had never seen, heard music I had never heard, and learned things I had never learned. The home movies are amazingly intimate, and the interviews with Ruth Underwood are enormously revealing and moving. Her piano performance of ‘The Black Page’ is the best I’ve ever heard, worth the price of admission all by itself!”

“As a young teen in England, 1969 was the beginning of my music obsession,” offers Alan Watts. “Cream, Led Zeppelin, the Who, the Stones, John Mayall etc. All guitars and British Blues.

“Then a year later I heard something very different: Hot Rats. Fantastic guitar work, but also the first time I ever appreciated a sax solo and jazz based compositions. Looking for more, I browsed through the Zappa section of my local record store only to come across album titles and covers the like of which I’d never seen before.

“They were from a different world to Led Zeppelin II, Tommy, Live at Leeds etc. Uncle Meat, Burnt Weeny Sandwich, We’re Only In It for the Money, and my all-time favorite, Weasels Ripped My Flesh. What a title; what great cover art!

“Where on earth did all these things come from? Nowhere that was remotely familiar to me. Up there with these was Lumpy Gravy. Like We’re Only In It for the Money, it was recorded in 1967 but not released until the following year because of the sorts of legal issues.

“Overall I thought ZAPPA was a great movie that captured the depth, creativity, singlemindedness, intensity, and craziness of FZ. I liked the generally chronological order, but I found my attention drifting a bit towards the middle, particularly around the parts dealing with the Flo and Eddie band. Perhaps that’s because I find this period his least interesting (IMO, 200 Motels was the worst major project FZ ever did).

“However, things picked up dramatically in the second half,” adds Watts. “I found the content in the remainder of the movie riveting. It captured the most interesting aspects of FZ, with a nice balance of music (guitar—but more on this later--and non-guitar), political activism (for want of a better term, and one that FZ would likely have hated), and personal insights into his life, concluding with his premature demise from prostate cancer.

“Best moments: Hearing from Bunk Gardner and Ruth Underwood. Priceless! The Kronos Quartet. I wish FZ would have written more small ensemble music. The 1992 Yellow Shark rehearsals and performances with the Ensemble Modern. I found this footage really quite emotional. In some respects, this segment highlighted the music format that was probably his deepest passion.

“The Ruth Underwood and Joe Travers ‘Black Page’ duet, with very effective comments from Steve Vai and Ruth. The comment from Vai about how FZ could drive musicians to go beyond what they themselves thought possible reminded me of a similar ability possessed by Miles Davis. So that’s a comparison at the highest level.

“Highlights: The early family movies. The ‘Phase 1’ Mother of Invention band movies, particularly the Garrick Theatre footage. I had heard this existed, but I’d never seen any of it before. Bruce Bickford (sad to see him looking so ill). FZ giving the tour of the vault, what a treasure trove! The short clip of a Vinnie Coliauta/Arthur Barrow duet. Coliauta and Bozzio were Zappa’s two best drummers IMO, and the competition for that accolade was fierce.”

“I met Frank in 1965 when he lived in a little place in Echo Park in an old California court yard apartment in Echo Park,” remembers Denny Bruce.

“He had records that filled up his bath tub. These are the records that informed his albums. The discs are his touch stones. Every record was there for a reason. He couldn’t live without them.

“In summer of 1965 as a drummer I worked with Frank Zappa in the developmental stages of the Mothers of Invention. We rehearsed for a few months and did a couple of shows, including one at The Brave New World in Hollywood as well as the landmark event GUAMBO-Great Underground Arts Masked Ball and Orgy at the Danish Center.

“I was always proud of everything he ever did. I’m honored that I knew him. I made him laugh and he liked all my ideas.

“The Frank Zappa who I knew in the 1965-1967 period… What I liked from first-hand experience was two things: He would have the ability to process all the information going on around him. I mean, I don’t mean reading or listening to music. I just mean focusing on conversations he might have had. I had been to San Francisco in 1966 and we crashed in somebody’s pad and when we woke up there were 20 people. I just described the scene to him and later that day, from our dialogue and conversation that cat was able to turn it into ‘Flower Punk,’ an anti-hippie song.

“Zappa worked very hard. That guy in my mind, with coffee and cigarettes, put in 24X7. He was always working and I know he enjoyed working all night because it was quiet. His genius is hard work. Very intelligent. Deep-rooted he knew he was ugly and had to out- work the other guy.

“That was his genius. And it made sense that he would put out an album in ’67, Absolutely Free because he was. Not paying attention to convention and the grin and grip stuff you have to do to get your product out. It all was like water rolling off a duck’s back. ‘Cause he did look freaky without trying. OK?

“Zappa never fuckin’ remotely talked about stardom. He talked about figuring out how you make enough money to be able to keep a band together. And how to make enough money to hopefully make the music you’re hearing and you’re trying to write down and compose so that ultimately guys can play this music. ‘Jimmy Carl Black and Denny Bruce aren’t my dream drummers but they’re loyal good guys.’ Jimmy and Frank went back to being in a band called the Young Giants. Ray Collins was the lead singer. I later managed Jimmy in Geronimo Black.”

“When the first Mothers of Invention LP Freak Out! came out I bought it immediately,” reminisces Carol Schofield. “I went to a friends’ house and sat there listening to it in the dark smoking a joint.

“In 2008 I was fortunate to release Don Preston’s original music composed and performed soundtrack to Gary Plays: Trilogy of Plays by Murray Mednick on my Citadel Records label.”

“Lumpy Gravy was Frank Zappa's first solo album, and in some respects, his most important music to date,” stresses Gene Aguilera.

“The project began when Capitol Records ace producer and A & R rep. Nik Venet approached Zappa to compose and conduct an album's worth of orchestral music. When Capitol made it available to the public on August 7, 1967 (but strangely only on the 4-track cartridge format). Verve soon found out and sued for contractual breach, and the product quickly withdrawn.

“Lumpy Gravy was officially released on vinyl by Verve Records on May 13, 1968, a mere two months after the Mothers of Invention musical masterpiece We're Only In It for the Money. But, Lumpy Gravy was the secret album, the idiot bastard son, and extension of We're Only In It for the Money (as both were recorded simultaneously). Over the years I began to appreciate why Zappa’s conceptual continuity was so important to understanding his work (‘It’s all one album’).

“The 50-piece ensemble, named Abnuceals Emuukha Electric Symphony Orchestra, was conducted by Zappa and included crack Hollywood studio musicians (such as guitarist Tommy Tedesco, drummer Shelly Manne, and Pete Jolly on piano) along with assorted members of the Mothers. The Zappa flashes of genius (or insanity) continued on in a wild collage of 'field recordings' using sophisticated mixing effects. It’s amazing what Zappa could do with recording tape, a razor blade, and a lot of inspiration.

“I once told Zappa at UCLA's Royce Hall that I've been playing Freak Out! since I was 13 years old to which he quipped, ‘And your neighbors still talk to you?’"

“I went to the Freak Out recording sessions at T.T.G. studios. I loved Frank and the records,” happily confessed Howard Kaylan. “Back in that era in 1966 and ’67, before the Turtles’ ‘Happy Together’ hit and Mark Volman and I were still L.A. street people working in the same clubs and stuff, there was enough of a camaraderie there. Knowing him, but also through [manager] Herb Cohen and going to the Zappa log cabin in Laurel Canyon.

“I go to the Freak Out that night. There are two or three rooms that are being used simultaneously, and Frank had tape recorders going in all of them. There are different tracks being played in all of them, and people are doing different things in every room. Frank would put some guys in one room, and some in another. The environment was more Soupy Sales than, say, Spike Jones. He’s creating his own scenarios. He’s making people go up to the mike and either rant in their own language, or getting them to say things. I think I was doing a little bit of both. Then I went into another room, where it seemed to be like an orgy, and that’s where [Tom] Wilson was. I knew who he was. I was aware that he was the guy who produced Dylan and many other gems. They were just recording random couples and noises, and people who had not met each other before. Frank would actually direct them physically, almost like he was directing a movie. It was surreal and great. I really wanted to be a part of it. It was so outside of my normal, structured thing.

“I had no idea, and still don’t know, how much stuff was ever going to be used. Brilliant editing job. Still a masterpiece, in my mind. But as far as the commerciality of the venture, I didn’t really think for a minute that it had any potential whatsoever. I’m sure he didn’t think my idiot pop songs had any potential whatsoever.

“Frank was singing about growing up. I was trying to sing about growing up, too. It wasn’t that far apart. Nobody made distinctions in that canyon of dreams back then as to what type of music you were doing.

“I worshipped We’re Only In It For The Money. One of the greatest rock records of all time. The cover art, too. It was better to me than the Beatles were at the time. There was a lot more content. A lot more undertone. A lot more sub-plot. A lot more ‘Wake Up America’ kind of thing.

“Whether it was real or imagined, I thought that Frank was the most brilliant writer that I had ever seen. Socially, since Dylan. I loved the Beatles stuff, and not to take away from it, but this was new. I wore out copies of it. 8-track. I had it every place.

“And it wasn’t just power, it was just a mastery. There was some deep compassion in the man that it actually was very empathetic. He could listen, whether he was listening for his own personal gain later on to turn that into money later in the creative venture or not.

“Well for me, it wasn’t so much we did on stage it was Frank’s demeanor off stage that made him paternal to me when Mark and I joined his band. And it wasn’t just power, it was just a mastery. There was some deep compassion in the man that it actually was very empathetic. He could listen, whether he was listening for his own personal gain later on to turn that into money later in the creative venture or not.

“Well for me, it wasn’t so much we did on stage it was Frank’s demeanor off stage that made him paternal to me. On stage he was a band leader and we were guys for hire. The fact that we got away with improv only meant we were smart enough to know when to get out of a bit in time for the music to come in. That’s what Frank respected. You could go off book as long as you got right back. No beats were lost and something was added. If you added something to the routine it was always appreciated and repeated if you could on a nightly basis or made to be part of the folk lore in some way.

“If it was not appreciated, Frank would let you know right on stage in no uncertain terms that this was not the time nor the place for that kind of thing. And later you would discuss it with him. It wouldn’t be a slap on the hand parent kind of talk. It would be very familial, more brotherly than paternal, but something that I never had before, which was an older figure that I respected respecting me back. The only other older figures in my life had been agents and managers who pretty much lied to me.”

“I was a big fan of Frank early on. Howard and I from the Turtles were around the Freak Out and we later saw Frank and the Mothers of Invention in New York in 1967 when Frank and that band had a residency at the Garrick Theatre,” recollected Mark Volman. “We were invited to Frank’s apartment in New York after one of the shows.

“Herb Cohen, Frank’s manager, invited us to go to the UCLA show with Zubin Mehta in 1970. Herb was a second cousin of Howard Kaylan, my partner in the Turtles. We knew the ‘California mentality’ that defined Frank. We bonded over doo wop and soul music.

“After the UCLA show we were asked backstage. Frank then invited us that weekend to a barbeque at the Zappa’s house. We brought our families. Frank told us to bring our saxophones. He took us downstairs to the ‘dungeon of horror’ and played some music for Howard and me. He quickly saw that we were not sax players. He said, ‘Look, we’re going over to England for eight shows. How would you like to come along and sing?’ We also did some U.S. shows and recorded with him for the first time a piece of music that came out on Chunga’s Revenge. We did some other songs in the studio with Frank including ‘Rudy Wants To Buy Yez A Drink’ and ‘Would You Go All The Way?’

“Frank was a Mother but we were Turtles, and he always wanted to know about our experiences. He thought we were stars. To him, the Turtles were like the Beatles. ‘What was that like?’ We told him a story about groupies; how these girls would do anything we wanted sexually if we would just sing ‘Happy Together’ for them.

“With that story began a two year relationship culminating in the motion picture, 200 Motels. Frank let us go through a litany of Los Angeles things that were in the live Fillmore East album. We were singing the praises of one of the greatest cities in the world. Like Frank, we were Los Angeles children. 200 Motels becomes the embodiment of our time with Frank. And we did Just Another Band From L.A. with him. After Chunga’s Revenge, we had what I used to call, ‘studio survival sessions,’ which is music he had recorded live and then we would work on it in the studio and clean it up. Some of those recordings were taped in concert. He recorded every show we did over 2 years.

“Rehearsing with Frank was scary. He was the embodiment of a union man. There was never a time for fun. Putting together ‘Billy the Mountain’ was a series of vignettes that connected around a 43 minute opera. Howard and I usually started with Frank on guitar, the three of us, and we were given the music to learn. Frank felt most comfortable playing and singing the melody so there are very few times where Frank placed himself into the four-part harmony or three-part harmony. He kind of left that to Howard, Jim Pons, and me. We’d take the bit and show up at the rehearsal hall on Highland Avenue and lead the band through what he wanted.”

“Frank Zappa first played an important role with me with his band, the Mothers of Invention, which I didn’t like in eighth grade, then totally loved in ninth grade,” volunteered Jello Biafra.

“I was only beginning to realize that you could mix rock music with good lyrics—at least, lyrics that would upset the right people. Thus I got into Alice Cooper. Then Zappa hit all kinds of raw nerves, ’cause he was satirizing the same kind of people I had to go to school with and stuff.

“I even tried to do a stage play of ‘Billy the Mountain’ from Just Another Band from L.A. when I was in high school. But it was a class assignment, and some of the people were not into it at all. It didn’t really come out very good.

“Even then, Zappa wasn’t just cynical about the people he called ‘plastic’; he went after the stupid side of the ‘Summer of Love’ and the escapist side as well. And right there at the beginning, [he] was pointing to a possible government role in manipulating people through drug abuse. Frank was the first one who laid it out to me that it was possible to talk about these other things that concerned me but put it with interesting music at the same time. Of course, his sense of humor was amazing, and I saw a lot of people around me through the same lens that Zappa saw people.”

“I knew guitarist Elliot Ingber who was working with Frank before the Freak Out LP recording sessions from the late 1950s’ from a restaurant in L.A. on Pico Blvd,” asserted Kim Fowley. “It was owned by singer Timi Yuro’s mother. A lot of the up and coming musicians, songwriters, musicians and producers would eat there. Timi’s mother would give us discount spaghetti dinners.

“It was at Canter’s delicatessen one night in early 1966, when I marched in doing my rounds and there was Elliot sitting with Frank Zappa. And I saw the hustle, because, obviously, when I walked in, Elliot said to Zappa, ‘This guy here has the juke vibe.’ And described what I was capable of performing live in code between the two. I knew all the code moves. ‘Elliot here says you’re God on stage.’ ‘He’s right! I can tear up a crowd. I’m not the greatest singer in the world but I know how to control an audience and hypnotize them.’

“Zappa was another guy in the mid-‘60s standing around in Laurel Canyon clothes, nothing more, nothing less, somewhere between a beatnik and a farmer. So, we went that night somewhere where they had their equipment and I said, ‘Play something!’ And I made up a song on the spot and he said, ‘You’re in the band if you wanna be.’

“Frank said, ‘We’re going in the studio to do what we did tonight. I have some stuff the band and I have learned. We’re gonna turn the street loose in there and you can come down and make noise if you want.’ I’m on the track ‘Help, I’m a Rock.’ I walked into the studio with Les McCann and Danny Hutton. I lived earlier in the attic of a house owned by his mother. Danny had already had his own hit with ‘Roses and Rainbows.’

“Ray Collins, great singer. Tremendous. He was the Roger Daltrey, and Frank was the Peter Townsend. I liked Roy Estrada. Zappa was like James Brown. He knew how to pick a band of sideman. He knew how to get ensemble playing done, like Sly Stone, too.

“T.T.G. Studios was a giant cheeseburger box with high ceilings. Owned by a sound engineer, an Israeli named Ami Hadani, who built studios and worked with Wilson and Zappa on Freak Out and Absolutely Free. Bill Parr built and designed the T.T.G. board in the big film-scoring room upstairs. He was one of the engineers on the Hollywood Argyles’ ‘Alley-Opp’ that we did at American Recorders. Jimi Hendrix later recorded at T.T.G. and cut one of my songs, ‘Fluffy Turkeys.’

“For Freak Out we were there all night. We didn’t get paid. We did it because Frank convinced us it was historical and we were on the cusp of something and we all bought into it. We all wanted to go have breakfast. That was more important. The Freak Out! album to me was John Cage meets 1920’s France. A Josephine Baker version of art is anything that you can get away with. I thought Frank was gifted. I thought musically he was brilliant.

“Lyrically, the words were so fast food that they took away from his majestic compositional talents. And Frank could have been Phillip Glass or Dimitri Tiomkin . He might have, should have, or could have gotten into serious composing in terms of orchestras and composition or, composer in residence, somewhere. It might not have been a rock ‘n’ roll choice. The lyrics were kind of cute. But the music was majestic and important sounding. But then again, he was protesting by orchestra arrangements with lyrics because those were the times of anti-authority and pushing the envelope.

“As a guitarist he was very good. He had the tone. I think if he were alive he’d have Lady Gaga in the studio doing something. He produced Grand Funk Railroad. Ezra Mohawk who worked with Frank sang on demos for me.

“I don’t think the word no existed for Frank Zappa. If he thought of it, he could do it. And if nobody would let him, he’d do it anyway. Gail Zappa has done a great job overseeing the Zappa catalogue and library and Frank in his work and career encouraged and positioned a lot of musicians. Frank Zappa was an internal creative timeless artist who dared to be different. And he combined various elements of classical, rock, beatnik, jazz, Hispanic, Latin, Eric Nord, Pharoah Sanders represented, possibly Spike Jones, or Raymond Scott.

“Frank was able to bring that to a dip shit teenage moron dope smoking audience on his terms. And in Europe he is decorated the way Jerry Lewis is honored in France for his contributions, as a poet, maestro and visionary.”

“What I love about Zappa is the way he connects to the pre-Beatle world of American bohemianism,” underscores Daniel Weizmann.

“Even long after he became the reluctant king of hippiedom, Zappa always struck me as a beatnik at heart, with that same Mad Comics trickster spirit of Lenny Bruce, Russ Meyers, early Bukowski, Venice cats like Lawrence Lipton and Stuart Z. Perkoff, and the whole crosshatch of subcultures that were just under the surface in Cali '59 to '63--bikers, surfers, poets, bongo-heads all pulling for exotica, for erotica, for something else—‘the left behinds of the Great So-ci-e-ty!’ (Cue the kazoos!) Case in point: In early '65, Zappa got busted by a vice squad undercover officer for agreeing to produce a ‘sexually suggestive reel-to-reel’ for a stag party.

“His trip was never just about music, no way. Zappa was a straight-up tummeler--the Yiddish word for soup spoon--a stirrer of pots.”

Alex Winter - Credit: Philip Cheung

Harvey Kubernik and Alex Winter Interview

Q: Did you view any documentaries in preparing for the ZAPPA endeavor?

A: The reason I wanted to make this film were my favorite documentaries that inspired me to make films in the in the first place. The work of D.A. Pennebaker, Dont Look Back, David and Albert Maysles’ Gimme Shelter, and towering above all of those was [the Rolling Stones unreleased 1972 tour documentary] Robert Frank’s Cocksucker Blues which had a huge influence on me when I was young.

The work of those photographers, some of whom made films, had an enormous impact on me artistically. So I didn’t go back and go on a diet of documentaries to view. That’s the stuff I liked to watch all the time.

In fact, sometimes I don’t even identify with some of the newer forms documentary is taking. I can appreciate them but I don’t viscerally connect with many of them the way I connect to Robert Frank or Pennebaker’s work, which is so huge.

At NYU I studied with Larry Clark and other instructors. Mike Nichols my editor and had a lot of discussions around Cocksucker Blues. How the camera had its own identity, how the director had a POV without having to be guiding the film with narration or a literal POV. Just an immense connection to that type of work.

Q: This decade a number of music documentaries being financed and distributed and the constant growth of the pop culture documentary market. They are programmed on streaming services and ever-expanding platforms.

In the last few years there have been documentaries on Herb Alpert, James Brown, Laurel Canyon, Tower Records, Bob Marley, Taylor Swift, David Crosby, Joni Mitchell, Harry Chapin, Suzi Quatro, MTV, Jimi Hendrix, Motown Records and Blue Note Records. Documentaries currently are being produced on Brian Wilson, I.R.S. Records, Del Shannon, the Quarrymen, Tom Wilson, the Velvet Underground, and Dion DiMucci.

Do you have any theories about the growth in demand and viewership that’s been established for music documentaries? I just did my second book on this subject. Is it because the audience wants a deeper look at the classic rock artists they dig and that their music catalogs from 30-60 years ago are still so potent and popular.

A: I think it’s both. There is no doubt that the rise of streaming at the same time at the bottom cratering out of the independent film market that was very robust and much simpler to make films geared for grownups that is much harder and it has been for quite some time. Those two things combined gave rise to a new golden age of documentaries where there were more people making films geared for grownups in a market that had been before quite dry. And then there were all these streaming channels that were interested in buying that content. So suddenly we have this world where we are in now.

To your point, yes, for many years, and we kind of touch on this in the [ZAPPA] documentary, really since the MTV generation did was it created an absolute deluge of kind of behind the music examinations of popular music that were very superficial, a cavalcade of talking head celebrities talking about who they loved and why, very little artistry if any artistry at all. And very little sense of depth or substance. And, I think there has been a rebellion against that.

There have been great music documentaries made during that time, and there were phenomenal music documentaries like Dont Look Back and Gimme Shelter made before that time. But I think there has been kind of a rebellion by the public against that kind of content, and a rebellion against this idea of making something that is shallow and artless, stacked with celebrity interviews.

Q: Tell me about the genesis and startup of your ZAPPA expedition.

A: We were coming off a couple of pretty heavy documentaries, and I was looking for something to do which had some levity. I tend to be drawn to subjects that have some position within culture. And have some impact on that culture. And I’ve been a lifelong Zappa fan and [producer] Glen [Zipper] and were tossing ideas around and wondering why no one had told this story. It just seemed like such an important story, and a good one and one that had a lot of the themes that tend to interest me. And I loved Zappa’s humor and the way he came at his art and his politics and sort of his life in general. So, that was kind of the impetus.

We sought out the rights, and of course, that was Gail Zappa. And we got a meeting with Gail. I pitched her a take and thought it will either be 20 minutes out of my life, no harm or foul. And, she was really taken with the perspective that we had, which was great. And off we went.

Q: And your focus was a serious examination of Frank Zappa’s life.

A: That is what I pitched Gail at the very beginning. Was that I wasn’t particularly interested in making a rock ‘n’ roll music movie, and I wasn’t even interested in making an album-to-album Zappa movie.

I really wanted to look at what it was like to be someone like Zappa at that period in American history and the commitment that he made to his art and what that cost him personally. And I wanted it to be warts and all. And I didn’t want to whitewash him. I really didn’t want to make a legacy film at all. ‘Here’s this great guy and all this cool stuff that he did.’ So, that was never our agenda. And I think that really appealed to her.

I laid that out from the very beginning ‘cause I really didn’t want to travel down the road if that was gonna shock them at some point because I also needed final cut. And, of course, I wasn’t going to bamboozle her into giving me final cut on something that was not pitched as advertised.

Q: You had total access to the vast Zappa archives. That surely was an asset in creating and assembling the portrait.

A: The thing that benefitted us, which we weren’t entirely aware, would be as beneficial when we started was how the project evolved. Meaning, my pitch to Gail, she loved the idea, I started filming interviews with Gail out of my own pocket years before we actually had the budget to start making the documentary. In fact, she wasn’t alive by the time we started making this documentary, which I didn’t realize was going to be the case. So I started filming interviews with Gail, and at the same time I was very concerned about the state of some of the material in the vault. Given time will have its way with anything especially old film.

The family did a very good job of preserving the music and the majority of media that was of significance. But it was a vast collection of material and far too much to get all of our arms around. So, for the next couple of years we really were only a preservation mission.

I did this Kickstarter campaign where we raised a great deal lot of money that I was very grateful for. And every penny of that went towards preserving the material in the vault that was in danger of deterioration. At that time I did not have financing for the documentary.

My team and I were in the very arduous and complicated process of preserving all this material. But what that gave me and my editor Mike Nichols was having a lot of time to look at that material. And organize and catalog it, and figure out exactly what we had so by the time we did get financing we had a really good idea of what was in our hands. I never really set out to make out an 8 hour version and then we would edit it down. I had a really specific narrative in my mind. There is an endless supply of concert DVD’s, movies for fans who want that kind of thing. And I had a real specific idea in my mind about telling a specific kind of story.

I never in a million years even desire to try and encompass all of Frank’s life in one film. I knew I could be selective with the biographical elements in terms of what helped us to tell the story. There is a great wealth of music to plunge into that he left us with. So I was really focused on a very specific story and so was Mike Nichols the editor. Together it made it much easier to determine what of all of his media we wanted to use and what we didn’t.

Q: Can you discuss the handful of interviews you conducted weaved into the documentary.

A: I wanted to have as few interviews as humanly possible. I wanted the film to be primarily archival with as much Frank’s presence that I could get. But I didn’t want to not have interviews just for the sake of having a film which presented itself as all archival. I felt that would have been unfair and would not have allowed me to have the benefit of greater perspective.

Also, I was able to ask very specific questions that I wanted to ask to get the answers that I was looking for in terms of certain aspects of Frank’s life, his nature and his heart. I knew some of these subjects would get into his interior life in a real meaningful way, which we got, of course, from Ruth Underwood, Steve Vai, and others.

The way I conduct interviews in general is a combination of very specific questions leading in a very specific direction combined with leaving the conversation open enough to free form enough that I can go in some directions that I don’t expect.

Q: What emerged after you finished the final cut that we get to view? You have chronicled an independent force of nature.

A: So much. I knew the facts of his life and I knew a lot of the details of his life. But being able to deep dive into his tenure at the Garrick Theatre in New York, for example, was extremely impactful, emotional and inspiring.

Being able to dive into all that video footage of Gail running Zappa Records and just sitting on the floor with piles of albums and ultimately CD’s and building an independent record label at the time was unheard of in a way. Very inspiring.

Again, I knew the facts of these things but that is why I like making films because there is nothing like the visceral impact of engaging with them as visual media. That had a big influence on the way I shaped the film. But it also was amazing stuff to find. Frank was extremely aware of the commitment you make to be open to your public when you lead that kind of life.

Frank Zappa was not only a creative genius, but also a great and eloquent thinker who articulated the madness of his times with extraordinary clarity and wit. A legitimate maverick who lived and worked amongst other extraordinary people in historic times.

Sure, he worked really hard, and he was locked up in his home studio, but he was not at all disconnected from the people around him. And he was not in accessible to them. And so to me, and we play with this in the film, to me became a very organic line once it was harder for him to make his albums, harder for him to go on tour. He would really just roll up his sleeves and dove into the public life doing civic work. The voting rights work, the senate hearings against censorship, the work he did with Vaclav Havel in Czechoslovakia.

He earned his audience and was very appreciative of that audience. And he was not the kind of artist that didn’t care what the audience thought of his work. He was a showman. And he had this since he was very young. A teenager. He was aware of the service aspect of making art in that way.

Q: There is a soundtrack album for ZAPPA issued by Zappa Records/Ume. I’m sure in the future there will be a DVD of your movie, hopefully with some bonus material. What are your feelings about bonus features and commentary added to DVD and streaming configurations after initial theatrical release of your movies? Do extra items and director commentary dilute the original artistic intent?

A: It depends on the project and I’m usually very cautious about what material we will share so that it doesn’t dilute the project or doesn’t somehow weaken the structure of the narrative. ‘Cause obviously documentaries are narratives as much as anything else. So, that has a very specific and I would say somewhat fragile internal architecture that you don’t want to tamper with. That being said it can usually withstand a few items from your edit bins.

So I think a little of that goes a long way. Commentary I don’t have a problem with. I’m not particularly interested in commentary but sometimes it is purely entertaining. There are certain filmmakers that are very funny or very entertaining and it’s fun to hear them riff about things. I wouldn’t turn my back on the entire world of kind of cinephile and collectors just because I don’t happen to be that sort of cinephile. I’m pretty much a purist when it comes to absorbing the narrative that was intended for me to see and not really needed for me to dive in much deeper other than reading a book about a filmmaker.

But I do think it that it is fun to give a little bit of extra stuff. And I think that is part of the new climate we are in. There’s a lot wrong with it but some of what is right with the streaming and technology advantages we have today is that the audience that is hungry for this stuff can get some of it. That they are serviced in that way. I have no problem with that at all.”

A short version of this article was initially published in Record Collector News magazine in November.

GARY PIG GOLD WAS ONLY IN IT FOR THE MOTHERS

The first Friday of most every month throughout 1967 and into ’68, I was formally excused from school so that my mother could take me all the way into Toronto for orthodontic appointments. As my due reward afterwards, I would be treated to a tasty french-fry-and-chocolate-milk lunch in the sumptuous Eaton’s Department Store cafeteria, then left for an hour alone in the adjacent Music Department while dear mom ran her errands elsewhere.

Gawd, I truly was deep in pre-teen heaven in there, believe you me: Guitars – just like the one Tommy Smothers played on TV every week! – lining each wall, while right over there were more record albums gathered alphabetically together in one place than my wide young eyes had ever ever seen.

But it was while methodically flipping through that “Misc. M” bin one innocent Friday in search of the latest Monkees long-player that I came across an image which shook me to the very core of my hitherto safe, sound, Micky’n’Mike-loving spine:

A foreboding, dark purple sci-fi sky shot through with lightning bolts, beneath which were strewn an above-motley crew of comic-book cut-outs – some of whose eyes were obscured with sinister black bars! And in front of all that stood what appeared to be a group of bearded, ugly, definitely NON-Monkee-looking men wearing… wearing dresses and standing by a mess of rotten vegetables which for some reason spelled out the word “mothers.”

Subconsciously at least, I recognized this was sort of, for some reason, like the picture on front of my latest Beatle album. But I also instinctively gathered something BAD was afoot.

So for the next several months, as if revisiting a decaying body rotting in the back woods, I’d patiently let Dr. Shanks, D.D.S. rip around my mouth, rush with Mom to scarf down some Eaton’s fast-food, then creep back towards those record racks to check if …IT… was still hidden there. Why, one grave Friday I even showed the offending, but somehow alluring record jacket to my mother …who, immediately sensing things untoward indeed, said “put that down, Gary. We’re going home.”

Flash forward a couple a years: By now, my comparatively straight teeth and I were enrolled in the local high school, specializing in Fine Arts and pouring over my latest charcoal still-life when the most incredible music suddenly burst from the record player at the back of the room. It was Eric Shelkey’s turn to bring vinyl in to accompany the day’s lesson y’see, and Eric, being by far the most freeeky, out-there student in all our Grade 9 Specialty Art class – I mean, the guy wore little round eyeglasses just like John Lennon, and his hair actually reached below his shirt collar! – certainly did not disappoint with his choice of music. Yep, instead of the usual docile strains of Tommy Roe or, at “worst,” Blood Sweat and Tears, the room was this morning filled with fully-stereophonic snorks, wheezes, electronic noises (much like those the microphone made in the auditorium downstairs when it wasn’t working), and some creepy voice which kept whispering “Are you hung up?” over and over again.

Understandably I suppose, just like my mother had back in Eaton’s music department, our hitherto pretty patient art instructor Mr. Pollard walked quickly to the back of the classroom, turned the volume all the way down, removed the offending twelve inches from the turntable, inserted it back in its sleeve, and told Eric he could pick his record up after class, thankyouverymuch nowpleasegetbacktoworkeveryone. Of course, me being me, I made sure to follow Eric out into the hall afterwards to find out the name labeled in the middle of this wondrous, forbidden twelve inches. Most obligingly indeed – but being careful to check both ways first to see if anyone was looking – he pulled the album slowly from his portfolio case.

AND THERE IT WAS. That same diabolical image which had haunted my post-orthodontic Fridays all those years ago!

Winking at me most conspiratorially, Eric invited me over to his place to listen to the entire record that day immediately after school. In fact, we even tried calling the telephone number which preceded “Bow Tie Daddy”! Then, I naturally saved up my allowance and bought my OWN copy a couple of months later, locked myself in my room… and it would be quite some time until I ever listened to Pisces, Aquarius, Capricorn and Jones Ltd. – or anything else, for that matter – quite the same way ever again.

I couldn’t say it then, but I surely will now:

Thank you, Frank.

(Harvey Kubernik is the author of 19 books, including Canyon Of Dreams: The Magic And The Music Of Laurel Canyon and Turn Up The Radio! Rock, Pop and Roll In Los Angeles 1956-1972. Sterling/Barnes and Noble in 2018 published Harvey and Kenneth Kubernik’s The Story Of The Band: From Big Pink To The Last Waltz. For summer 2021 the duo has written a multi-narrative book on Jimi Hendrix for the publisher.

Otherworld Cottage Industries in July 2020 has published Harvey’s 508-page book, Docs That Rock, Music That Matters, featuring Harvey’s interviews with D.A. Pennebaker, Chris Hegedus, Albert Maysles, Murray Lerner, Morgan Neville, Curtis Hanson, Michael Lindsay-Hogg, Andrew Loog Oldham, Dick Clark, Ray Manzarek, Travis Pike, Allan Arkush, and David Leaf, among others.

In 2020 Harvey served as Consultant on Laurel Canyon: A Place In Time documentary directed by Alison Ellwood which debuted in 2020 on the EPIX/MGM television channel.

Kubernik’s writings are in several book anthologies, most notably The Rolling Stone Book Of The Beats and Drinking With Bukowski.

Harvey penned a back cover endorsement for author Michael Posner’s book on Leonard Cohen that Simon & Schuster, Canada published in October 2020, Leonard Cohen, Untold Stories: The Early Years)

A short version of this article was initially published in Record Collector News magazine in November.