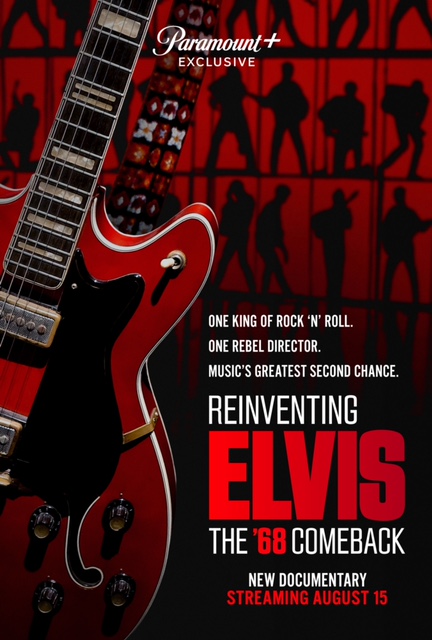

Paramount+ in mid-August will debut a new feature-length documentary REINVENTING ELVIS: THE '68 COMEBACK that is told from the viewpoint of director Steve Binder, who helmed the original Elvis...The '68 Comeback Special.

It will premiere exclusively on the service Tuesday, August 15 in the U.S. and Canada and internationally on Wednesday, August 16th in the U.K., Latin America, Brazil, France, Germany, Switzerland, Austria and Italy.

REINVENTING ELVIS: THE '68 COMEBACK Set For Mid-August 2023 Release;

Elvis...The '68 Comeback Special: A Multi-Voice Memoir

By Harvey Kubernik Copyright 2023

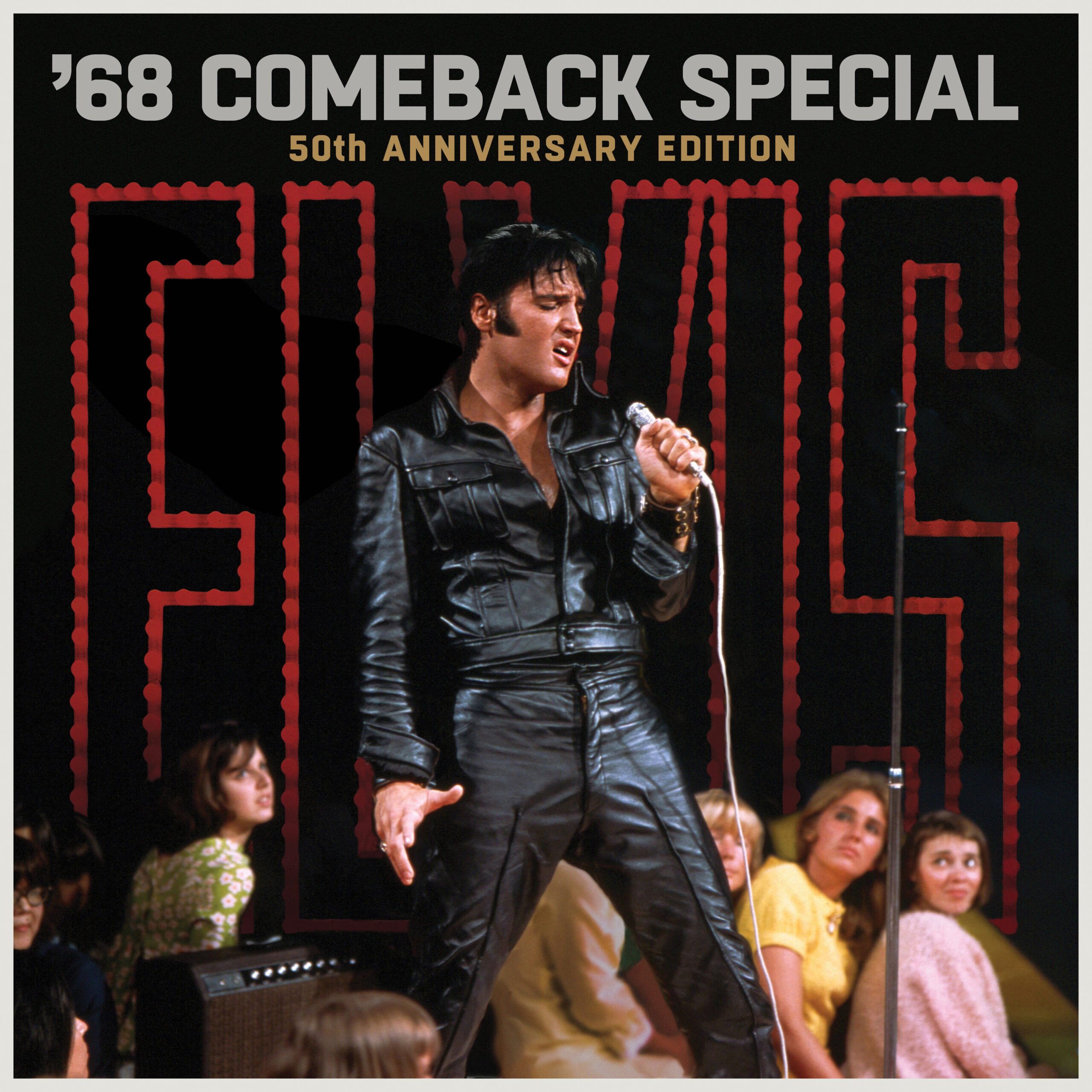

Premiering days before the anniversary of Presley’s death, REINVENTING ELVIS: THE ’68 COMEBACK reveals what really happened behind the scenes of this mesmerizing hour of television. When it aired on the night of Dec. 3, 1968, the special became the most-watched television event of the year, and nearly half of the entire TV-watching audience tuned in to see Elvis Presley, clad in an iconic black leather suit, deliver some of the greatest performances of his life, reinvigorating his career and changing the pop-culture landscape forever.

A media announcement from Paramount+ touts the upcoming Presley celluloid endeavor.

"Told from the unique perspective of Emmy® Award-winning television director Steve Binder, REINVENTING ELVIS: THE ’68 COMEBACK features interviews with Elvis experts and recollections from those who attended the special in-person, as well as all-new versions of iconic Elvis hits interpreted by contemporary musicians, including superstar Darius Rucker, Latin GRAMMY® winner Maffio and America’s Got Talent finalist Drake Milligan, who previously starred in CMT’s hit series Sun Records, also streaming on Paramount+.

"Prior to its streaming debut, REINVENTING ELVIS: THE ’68 COMEBACK SPECIAL will also screen for a limited time in hundreds of movie theaters worldwide with more details to be announced soon.

“The world is filled with stories about Elvis and his historic 1968 Comeback Special, but no one has ever told this story the way only I can tell it — because I was there for every moment of it,” said Binder. “I’m so proud of this film, because it presents Elvis as he really was, and looks at a specific moment in time — when Elvis took control of his life, his career and his legacy. There’s never been a television moment quite like this one.”

“The world is filled with stories about Elvis and his historic 1968 Comeback Special, but no one has ever told this story the way only I can tell it — because I was there for every moment of it,” said Binder. “I’m so proud of this film, because it presents Elvis as he really was, and looks at a specific moment in time — when Elvis took control of his life, his career and his legacy. There’s never been a television moment quite like this one.”

During 2007 I was a feature interview subject for the Viva Las Vegas deluxe edition DVD from Warners Home Video. In 2008 I penned the 5,000 word booklet liner notes to the Elvis The ’68 Comeback Special 5-CD box set issued by Sony/Legacy. I attended 6 Presley concerts in Southern California between 1970-1977.

Elvis Presley had entered 1968, that heartbreaking year, as barely a blip on the radar screen of a generation wallowing in a purple haze. Luxuriating high above Sunset Blvd, he gave little thought to the hordes marching up and down the neon Strip, content to placate his remaining fans with star turns in such disposable drive-in fare as Charro and Live A Little, Love A Little.

Presley was still issuing product of movie soundtrack albums but garnering nowhere near the sales figures of a smash hit like Blue Hawaii. It had been nearly six years since “Good Luck Charm” had topped the Billboard 100, an eternity for an increasingly impatient, impetuous and impertinent audience.

The arrival of Bob Dylan, the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, the Doors and all that followed in their wake, further diminished the relevance of an artist who burned brightest when girls wore poodle skirts and boys donned coonskin caps. His most recent single, a carousing treatment of Jerry Reed’s hook-laden “Guitar Man” failed to enter the Top 40.

Elvis hadn’t been on the small screen since The Frank Sinatra Timex Show for ABC television, welcoming him back from the service in May 1960. Parker shrewdly maneuvered a sweet deal from NBC-TV’s Tom Sarnoff. Ostensibly a boiler-plate Christmas special—Elvis bedecked in seasonal tinsel, singing treacle owned by Elvis and the Colonel’s publishing company, natch—Parker parlayed the network’s commitment to include financing for a feature film, which was becoming increasingly harder to secure. The show, sponsored by Singer Sewing Machines, was to be called, ELVIS.

What Colonel Parker hadn’t anticipated, though, was appearance of a joker in the deck, in the form of television director, Steve Binder, who, with his partner, engineer/music producer Bones Howe, set Elvis off on a personal journey that bordered on a career resurrection.

Dayton “Bones” Howe, came to Los Angeles from Georgia in 1956, prompted by drummer Shelly Manne’s admonition that there was gold (or, at the least, a possible career) in them there Hollywood Hills. Howe settled in behind the mixing console at Radio Recorders, as tape recordist under principal engineer Thorne Nogar on some the young Presley’s breakthrough hits.

Over the next decade, Bones Howe became one of the most celebrated engineers and then in the music industry, generating a parade on Number Ones from Jan & Dean, Johnny Rivers, the Mamas & Papas, the Association, and the Turtles. The West Coast sound was as much a product of this soft-spoken, jazz-loving gentleman as it was the worship of cars, girls and warm summer breezes.

“The first time I saw Elvis was at the Florida Theater in Sarasota, Florida when I was in high school. He was a young country singer. He performed between movies,” Howe told me in a 2012 interview. “I first did some work with Elvis in late 1956 and early ’57 in Hollywood at Radio Recorders.

“Elvis drove out from Tennessee in a stretch Cadillac with DJ and Scotty with the gear in the backseat. They came out to record with Steve Sholes, the A&R guy who was responsible for signing them on to RCA Records. He brought them to Hollywood to record them. RCA was doing all their recording in those days at Radio Recorders. Elvis and the guys stayed in Hollywood at the Roosevelt Hotel or the Plaza and later the Knickerbocker. I did some sessions with Thorne Nogar. He was very good to me and took me under his arm. I was a recordist and he asked me to do some sessions with Elvis. Elvis could never get his name right so he called him Stoney.

“In Hollywood I saw Elvis with his buddies. It was the first time anyone ever heard of block booking a studio for a month. We never had to tear it down. We could leave the studio at night. I worked on ‘Love Me’ and ‘Old Shep.’ I was around the session for ‘Return to Sender.’ Elvis never stopped moving in the studio. He recorded everything live. In those days you didn’t separate people so everyone was in the same room. Direct to mono when we started. The two-track that we did on Elvis had his voice on one track and everybody else on the other track. When we started with Elvis there was no stereo. He could sing a ballad. He could imitate anybody. Mention a singer and he would imitate them. Like Fats Domino. You would turn your back and you thought Fats was in the room,” noted Howe.

“Elvis would come in with Hill & Range music publishers and Elvis would record only their songs. They would show up with a box of acetate dubs and my job on those sessions, aside of running the tape machines was that I had a turntable there which was hooked up to the playback system. I would take these dubs out one at a time and put them on a turntable and play it outside to him. He would signal to me like running his finger across his throat if he didn’t like the song and I would toss it to another box. Or he would pat the top of his head. Meaning from the top again. ‘Play it again.’ And the guys would learn the song off the demo. There it all was for me. All in a nutshell. Demo. Artist. Song. Record. The Colonel never showed up or came to the studio. Maybe once to get some paper signed. Elvis ran the session and Steve Sholes ran the clock. ‘OK, Elvis. That’s 2:14.’ ‘Sounded good in here. Want to listen?’ Radio Recorders had the wonderful echo chamber in Studio B. A live chamber in those days. Not tape reverb. I watched Elvis become a huge star.”

Bob Finkel of NBC had recruited Binder to direct their weekly pop music series, Hullabaloo. TV specials featuring Leslie Uggams and Petula Clark solidified his credentials for bringing projects in on time, on budget and with the glint of danger. Elvis Presley was now in the capable hands of a talent to match his own. Finkel, Colonel Parker and Binder all agreed that it would be a one-man show, no guest stars, and RCA Records would have a soundtrack album for retail outlets.

Steve Binder was the right man at the right moment. Precocious to a fault, the Los Angeles native left USC just before graduating to apprentice under Steve Allen, who’s pioneering variety show broadcast was a hothouse of innovation and imagination. Binder, barely in his twenties, then took the helm of Jazz Scene USA andlater Hullabaloo, bringing live performances by musical masters to a network audience. Viewed today, it is clear that Binder understood the unique requirements of lighting and blocking that showcased musicians in an optimal setting.

In October, 1964, Binder directed The T.A.M.I. Show, a groundbreaking rock ‘n’ roll circus, that triumphed under his whip and chair direction. Hosted by Jan & Dean and starring James Brown, the Rolling Stones, the Beach Boys, Chuck Berry, Lesley Gore, the Miracles, and Marvin Gaye, amongst many others, this ninety minute feature culled from two days of production insanity, has rightfully earned legendary status, a template for every rock concert film.

"Going back to The Steve Allen Show and Hullabaloo where I was collecting people all the way through my career that I wanted to have in my team and work together with," Binder explained to me in a 2008 interview we conducted.

"And in those days, technically, union wise, you unless you had a union card you weren’t supposed to participate. I learned together the difference between making records and television audio. It was a perfect marriage. Even in lighting I would bring in rock ‘n’ roll guys who did concerts with guys bred on television and movies. All of a sudden they were learning about the contemporary music business.”

“Elvis and I hit it off,” underlined Binder in our interview. “I didn’t feel like the awestruck audience to a super star—just another guy my age. And we hit it off as friends when we were working. He’d come to the office I shared with Bones on Sunset Boulevard every day. Everyone on the team was treated equally, and Elvis joined us in that spirit. He did not play star one day on the entire shoot. We all got to pick the music. My TV special before with Petula Clark and Harry Belafonte was done at the same location at NBC in Burbank.

“I used John Freschi and Bill Cole who were on staff there as lighting director and audio head, set designer Gene MacAvoy, musical director and composer Billy Goldenberg and worked with Bones Howe. By the time we got to Elvis we had a family.

“I told Elvis in no uncertain words I was not going to do 20 Christmas songs. Elvis told me he was scared to death of television. He told me he was only comfortable makin’ records. He had been away from the public and was concerned they didn’t want him back. I told him ‘then why don’t you make a record album and I’ll put pictures to it.’”

Writers Chris Bearde and Allan Blye were recruited into developing the show’s script. Veterans of such whimsical assaults on middle-class mores as Rowan & Martin’s Laugh-In and The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour, they recognized a unique opportunity to walk the razor’s edge with a network’s witting compliance. If the final draft swerved just shy of Dada, it was through no lack of collaborative ambition with a fully-engaged star.

Goldenberg, a confederate from Binder’s job on Hullabaloo, viewed his assignment as a decidedly mixed blessing. A graduate of Columbia University and a protégé of the Broadway Legend, composer Frank Loesser (Guys and Dolls), he brought a rich harmonic sensibility to his work that ill-suited the caterwauling punch of fifties rock ‘n’ roll. It was only after Binder’s fervent pleading that Goldenberg agreed to meet with Elvis, let alone compose a raft of charts under a mind-bending deadline.

“From the very first meeting I liked him,” said Goldenberg in a 2008 phone conversation. “We had a great rapport. He always looked after me and was supportive. The most interesting thing to me once we started was the concept that developed. There was a movie soundtrack by Quincy Jones, In Cold Blood, probably the most interesting score I had ever heard at that point. It was a fusion of that kind of country redneck sound but at the same time something very classical underneath it all. Evil, sexual, and spooky. Elvis personified all of those things. And the music had to as well.”

Goldenberg was given free rein to assemble an all-star orchestra, drawing from both the NBC stable as well as distinguished free-lancers. But his real coup was reeling in the fabled Wrecking Crew, a pick-up team’s worth of studio hotshots who routinely delivered the goods on countless hit recordings. Although back in 1968 they were session players from the Hollywood Local 47 Musicians Union. Like their Detroit counterparts, the Funk Brothers, these were seasoned jazz cats that could blend a savvy professional’s hauteur with the laid-back charm of sunbaked Southern California.

“This was like a film that had to be scored,” reiterated Goldenberg. “The first thing I did was build a big medley around ‘Guitar Man.’ That was the test, actually. I went with that whole concept sequence—trying to make it as dirty and black and provocative and still being Elvis. We had the presence of those guitars that were very dark. His voice invited you into the arrangements. I wanted it all to be seductive. Because Elvis was the ultimate seducer. A starting point was definitely the work of the bass guitar. Once I had that kind of bass thing going on and there was a certain kind of mambo riff with it. It also touched on some of the Beatles’ darker stuff.”

In 1967 and ’68 keyboardist Don Randi was doing recording sessions with Neil Young and Jack Nitzsche during Buffalo Springfield, on dates with Love on Forever Changes, and on the Monkees’ Head soundtrack.

“Around the same period this Presley call comes in from Billy Goldenberg,” reminisced Randi to me in 2008 inside his Baked Potato club venue in Studio City. “I had done some soundtrack things earlier in the sixties with him. I worked on another Presley film, Live a Little, Love a Little. We cut ‘A Little Less Conversation’ with Al Casey, Hal Blaine, Larry Knectel the bass player and me on piano. In 1962 Jack Nitzsche was the pianist in the lounge band in an Elvis’ film Girls! Girls! Girls! Barney Kessel was on that soundtrack and others, and he played guitar earlier on ‘Return to Sender’ and ‘Can’t Help Falling in Love With You.’

“I never felt Elvis was a man out of time. What you have to understand is that his music never died. You know, at the time, a lot of people were saying he didn’t have a hit record for a couple of years; his career is over. I never thought that at all. It never would enter my mind. Because I know, from the first time I saw him on Ed Sullivan to the days I got to work with him, that this guy could go on forever. The only guy who will stop this guy from going on is himself.

“That night I got the Elvis call. I remember one thing, it was on a Saturday and we all were making a fortune. Double scale. Golden time. Big time. I know this was a little different for Elvis working with us. Sometimes he sang live with us and sometimes he overdubbed. As a matter of fact he sat down at the piano with me a few times for me to straighten out the part he had to sing on ‘Jailhouse Rock.’ We were on the incidental and interstitial music that was all over the soundtrack. He worked with us on the stuff. What’s more important than hearing Elvis in headphones is that I got to hear him as a human being, having chats, going back and forth. He had a musicality to him.

“Look, Elvis has innate musical skills. He did not remind me of Brian Wilson or Frank Sinatra. They are all so different. Which is a very interesting point. The individuality between those three people are from completely different places. They are all fantastic on their own and rightly so, because they worked that hard creating what they do and everybody is an individual there.

“I guess we were all taking Elvis into a different world. It was a completely different thing for him from the A band, or the Memphis band. Just having the Blossoms on the sessions. Elvis loved the Blossoms. He knew Darlene from her work with Ray Charles. Elvis was now playing with the Wrecking Crew. Hal Blaine, Tommy Tedesco, Mike Deasy, Tommy Morgan, Chuck Berghoffer, Frank De Vito, and vocal contractor BJ Baker.”

Drummer Hal Blaine had already enjoyed hit record success with Presley on “Can’t Help Falling in Love With You,” “Return To Sender” and “Bossa Nova Baby.”

“The ’68 Special was a great time. Elvis was terrific and loved us all because a lot of us had worked with him before,” divulged Blaine. “I was on the soundtrack of Blue Hawaii and Girls! Girls! Girls! ‘Hello. How are you doing?’ He was relaxed but sweated a lot. I had to hand him a Kleenex when he was wearing that leather suit. Elvis was Elvis and he was a phenomena. And that’s all there is to it.”

“There was a song that we did and he wanted to show that he had an operatic type voice. Just a big voice. To me he was Elvis. That’s all there is to it. He was a one of. People who generally become famous are one of. He was also very handsome and all the ladies were crazy about him. He was a decent guy. The Wrecking Crew could lock in with anybody. But with Elvis you’re gonna sit up a little straighter, maybe. I loved DJ Fontana. I hung with him a lot on the set.”

“Elvis decided to move into NBC physically for the period we were in production. We cleaned out the Dean Martin dressing room off of stage 4,” said Binder. “When we finished rehearsals Elvis would start jamming with his friends around the baby grand piano and anybody who happened to be there or invited in started jamming with him. So they would just play acoustically, banging on chairs, piano tops, and Lance LeGault brought his tambourines in. It went on for hours and hours.

“I thought, ‘this is like looking into a keyhole of something that only very few people get to see behind the scenes. I’ve got to get this on tape. I mean, this is better than what we are doing out there with all the dancers and singers, the production numbers. This is incredible; I am seeing the real Elvis now.’

“I was barred from coming into the dressing room with any kind of equipment. I started taking notes and brought my little tape recorder in and started recording what was going on. I kept it in my pocket so nobody knew what was going on. And then I started transferring the information I got onto paper. So I would remember what songs he sang and what he was talking about. Finally, I pestered the Colonel so much and he finally said, ‘You can go on stage and re-create what you are seeing in here.’

“When I told Elvis what we were gonna do, he was jazzed,” marveled Binder. “But he said, ‘If I’m gonna do it I wanna bring in [guitarist] Scotty [Moore] and [drummer] DJ [Fontana].’ ‘Cause Scotty and DJ were never a part of the special. Elvis wanted the audience closest to him and Colonel Parker picked what he thought were the most attractive women to be seated nearest.

“Then when it came time I handed Elvis the paper with my notes which he physically brought out to the stage and referred to in one of his takes. Right before he went out I got called into the dressing room. ‘I changed my mind. I don’t want to do this.’ ‘What do you mean you don’t want to do this?’ ‘My mind is blank. Steve, I don’t know what to sing and don’t know what to say.’ ‘Elvis, just go out. This is not optional. I haven’t asked you to do anything up to the point that you didn’t want to do. Now I am asking you to go out there. I don’t care if you just say hello or goodbye and come right back in five seconds. Just go out there.’ On the first take his voice is totally dry and he needs to get some water before he begins. He even stops the first eight bars in. His voice is cracking. And then you see and hear him building his confidence. You can see it on his face. You can see it on his body posture. He gets to the point where he doesn’t want to leave.”

It is a delicious irony that the most packaged, pre-meditated image in pop culture could reclaim his most authentic self in such a spontaneous fashion. Clearly scared to death, Elvis retreated to his strengths, surrounded by musicians who understood and relished the same impulse to simply sing and play. Elemental in its ferocity, the “sit-down” section is a time-capsule that students of music, let alone Elvis fans, cherish.

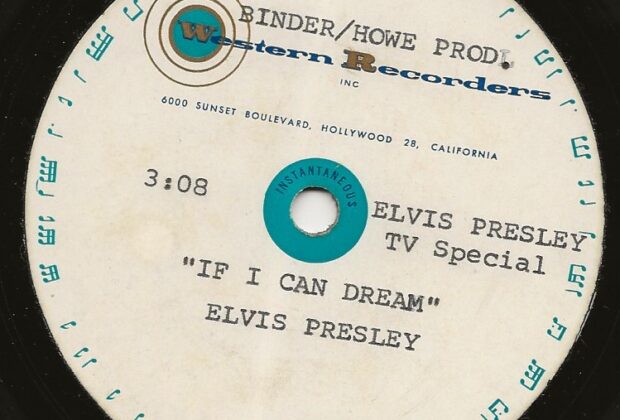

During the TV production, Elvis walked into Western Recorders studio on Sunset Blvd. and was alarmed by the amount of musicians and singers booked for the recording sessions,” proffered Binder.

“Elvis was stunned by looking at all these musicians and singers. He came in his dark sunglasses and all of a sudden I was in the control room with Bones. Someone came in, probably Joe Esposito and said, ‘Elvis wants to see you.’ I went out, he had a very serious look on his face… Something is not right. He said, ‘Come on outside with me.’ We went on to Sunset Boulevard. ‘Steve, I’ve never sung with anything bigger than a rhythm section in my life. I never sang with an orchestra in a recording studio. You gotta promise me if I don’t like what’s playing here you’re gonna send everybody home and just keep the rhythm section or I’m not going in there to sing.’

“And I had to promise him, which I did. There was great trust to begin with. First of all, he had never heard anything Billy Goldenberg had done. So I promised him if he didn’t like it I would send everybody home, the brass section and everybody and keep the rhythm section. We walked inside and Billy has a conductor’s little stand, and he invited Elvis to come up and Billy gave the downbeat to the opening song ‘Guitar Man’ and it was total love at that point. Elvis couldn’t get enough.

“We were all there late one night in our production office in Hollywood and watched the Robert Kennedy assassination on the TV set—that was cathartic to all of us,” acknowledged Chris Bearde. “We all sat around until 5:00 AM and Elvis told us his entire life story while playing the guitar and picked, not strummed, talkin’ about ‘Tiger Man,’ and how guys would throw punches at him so they could say they hit Elvis. He just rambled on and we listened for all those hours. Part of the conversation went to his background in Gospel singing and how he really was one of those white guys from the south who really understood not just his own rockabilly background but the music of the church.”

“We were in our office on Sunset Boulevard rehearsing one evening and the television was on in Bones’ office and Bobby Kennedy was assassinated,” added Binder. “And we stopped rehearsal and spent the entire night about both the JFK and Robert Kennedy assassination, and Martin Luther King before in April. Those are the kind of things that bond people…

“Earle Brown was a choral director on The Carole Burnette Show and in a music group, the Skylarks on RCA. I met Earle with Leslie Uggams. And I think ‘If I Can Dream’ was the song like a lot of people who write great one time first novels. I don’t think Earle realized what he wrote, and having Elvis Presley perform it was the miracle of all miracles.

“I was convinced we had to close the show with something powerful. Here we are with a black choreographer, Claude Thompson, a Puerto Rican choreographer, Jaime Rogers, the Blossoms, they are right behind Elvis on his side, and no one is saying anything. No one cares that we are mixing races,” beamed Binder. “I went to Billy Goldenberg and Earle and said ‘Guys you’ve got to write an original song that says the inner dialogue that we are hearing and feeling about Elvis Presley in these past few months. We’ve got to make a statement that he makes. Color doesn’t matter. Race doesn’t matter. He accepts everybody. I need that song. Go home and write the greatest song you ever wrote.’

“The next morning Earle called and said ‘Can Billy and I meet you at NBC an hour before Elvis comes in.’ I drove out to Elvis’ dressing room where he would dress and shower, and we had a little spinet piano in there and a baby grand in the main dressing room. So Billy sits down at the piano, and the Earle and Billy now play ‘If I Can Dream’ for me. I got goose bumps the first time I heard it. ‘You guys have done it. Congratulations. Fantastic. I’m gonna convince Elvis Presley to sing this song.’

“Realizing I had a shot with Elvis in really saying something, I felt strongly by Elvis singing ‘peace and love’ after all these 1968 assassinations it just seemed like the perfect song to say these words, And I think Elvis was a great deliverer of that message. Billy did the arrangement overnight and Elvis did five takes on the vocal. Colonel Parker did subsequently publish ‘If I Can Dream’ from the program.”

“When it was time to do the Presley pre-records this was the place because he was gonna sing live,” stressed Bones Howe. “With his hand taped to the microphone and complete with knee drops in front of the string section! He got all these violinists with their mouths hanging open. With some artists you can kind of plug in what the record is gonna sound like. But with Elvis you sort of were relaying on him to perform this piece. And he did. The soundtrack album version, not the DVD version, is the version that is the single. That’s him singing live in the studio. I gave him a hand mike on a long cable. Because I knew he was not gonna stand in one place. He’s gonna walk. ‘I’m the engineer. Don’t worry about it.’ He loved being in the middle of a bunch of guys around him. They were like his audience. Not many takes. Not more than four or five.

“He heard it for the first time with the orchestra right then and there. He didn’t wear headphones standing in the middle of the orchestra. It’s like being on a stage in Las Vegas. He nailed ‘If I Can Dream’ when we did it on the show. He was a great performer.

“Elvis sang ‘Memories’ live but then I did a track and he sang it afterwards. He wanted to sing it really, really softly. And we turned the lights out in the studio after the orchestra went home. With TV you have to have a track on everything. And I turned the lights off in the studio and he just stood out in the studio and sang it all by himself in the dark and we made two takes. And the second one is the one that is in the show.”

“When I played Elvis the edited 60-minute version of the show in a projection room at NBC and at the first screening of the show we had a lot of the staff that did the show, the entourage in the room, it was packed,” recalled Binder. “When it was over Elvis told everybody to get out of the room and he wanted to see it again with just me in the room with him. Elvis said to me in that room, ‘Steve, it’s the greatest thing I’ve ever done in my life. I give you my word I will never sing a song I don’t believe in.’”

The Elvis ‘68 Comeback Special was shown on December 3 at 9:00 PM. On December 4, when the ratings were released, NBC reported that Elvis captured 42 per cent of the total viewing audience. It was the network’s biggest rating victory for the entire year and the season’s number one rated show. Reporter Hal Humphrey in a December 4th story for The Los Angeles Times proclaimed “Elvis still generates considerable heat with his singing.” Robert Shelton in The New York Times wrote “Rock Star’s Explosive Blues Have Vintage Quality.” Writer and cultural critic, Greil Marcus, in his 1975 book Mystery Train hailed Presley’s ‘68 moment. “It was the finest music of his life. If ever there was music that bleeds, this was it.”

In early November “If I Can Dream” was released. By the end of the month it was Top 40 and eventually earned a number 12 slot on the singles chart in January of 1968. The soundtrack landed at the 8th position on the album listings.

“‘I Can Dream’ should have been the theme song of 1968,” declared author and keyboardist Kenneth Kubernik. “It’s right up there with ‘A Change Is Gonna Come.” Sam Cooke and Presley in 1964 both RCA artists and both songs recorded on Sunset Boulevard. ‘If I Can Dream’ reflects the nature of the Pentecostal church Elvis’ mother belonged too. And Elvis grew up in this sense, and the whole idea of having these world shaking individual transforming experiences was part and parcel of Elvis’ own upbringing in the world that he lived in. There was always this possibility of resurrection and re-invention. It was always a part of his religious upbringing.

“Whether he was conscious or not, that when he starts to sing a song like ‘If I Can Dream’ it doesn’t sound like it was just selected by the producer of the show. It sounds like Elvis is dialing it in like Sam Cooke convinced us with ‘A Change Is Gonna Come.’ This is the revelation for me. And the fact that Billy Goldenberg made the arrangement bass instrument oriented makes it come out of the bass note, actually an organ note, which is again a church note. It was a freakish recording. I think they caught lighting in a bottle on this.”

(Harvey Kubernik is the author of 20 books, including 2009’s Canyon Of Dreams: The Magic And The Music Of Laurel Canyon and 2014’s Turn Up The Radio! Rock, Pop and Roll In Los Angeles 1956-1972. Sterling/Barnes and Noble in 2018 published Harvey and Kenneth Kubernik’s The Story Of The Band: From Big Pink To The Last Waltz. In2021 they wrote Jimi Hendrix: Voodoo Child for Sterling/Barnes and Noble. Otherworld Cottage Industries in 2020 published Harvey’s Docs That Rock, Music That Matters.

Kubernik’s writings are in several book anthologies. Most notably, The Rolling Stone Book Of The Beats and Drinking With Bukowski. Harvey wrote the liner notes to the CD re-releases of Carole King’s Tapestry, The Essential Carole King, Allen Ginsberg’s Kaddish, Elvis Presley The ’68 Comeback Special, The Ramones’ End of the Century and Big Brother & the Holding Company Captured Live at The Monterey International Pop Festival.

During 2006 Harvey spoke at the special hearings initiated by The Library of Congress held in Hollywood, California, discussing archiving practices and audiotape preservation. In 2017 Kubernik appeared at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland, Ohio, as part of their Distinguished Speakers Series.

Kubernik was lensed for the 2013 BBC-TV documentary on Bobby Womack Across 110th Street, directed by James Meycock. Bobby Womack, Ronnie Wood from the Rolling Stones, Regina Womack, Damon Albarn of Blur/the Gorillaz, and Antonio Vargas are spotlighted.

Harvey was a featured talking head in director Matthew O’Casey’s 2012 Queen at 40 documentary broadcast on BBC Television and released as a DVD Queen: Days Of Our Lives in 2014 via Eagle Rock Entertainment.

During 2014, filmmaker O’Casey interviewed Harvey in his BBC-TV documentary on singer Meat Loaf, titled Meat Loaf; In and Out of Hell, broadcast in the US market in 2016 on the Showtime Cable TV channel. In 2019, Kubernik was an on-screen interview subject for director O’Casey on his BBC4-TV digital arts channel Christine McVie, Fleetwood Mac’s Songbird. The cast includes Christine McVie, Stan Webb of Chicken Shack, Mick Fleetwood, Stevie Nicks, John McVie, Christine’s family members, Heart’s Nancy Wilson, Mike Campbell, and Neil Finn).