As Johnny Cash prepared to perform his soon-to-be classic "Cocaine Blues" at San Francisco's Carousel Ballroom on April 24, 1968, he offered an introduction that is fascinating in its matter-of-factness: "here's another song from the show we did at Folsom prison. It's in the album that's out next week."

In that instant, nobody at the Carousel Ballroom - not Cash nor his Tennessee Three, not the show’s legendary soundman Owsley "Bear" Stanley nor the 700 or so hippies in attendance - could have known that casually referenced live album would become one of history's most illustrious and influential.

As Cash historian Mark Stielper has noted, this version of "Cocaine Blues" underscores the Carousel show as "the last picture of Cash before he was a prophet and a pilgrim and mover of mountains and a friend of presidents and the voice of God.” And, in this way, adds a wholly new chapter to the story of Cash's redemptive rise that's so extraordinarily documented on the Bob Johnston-produced albums At Folsom Prison and At San Quentin.

A press release from the record label describes the origins of this 1968 moment “another layer of singularity to the recording is the sonic touch of Owsley Stanley, the live sound pioneer and 60s counterculture icon known as the architect of the Grateful Dead's ‘Wall of Sound.’ While seemingly an unlikely pairing with Johnny Cash, Stanley delivers a mix that's been described as ‘probably the closest to what it actually sounded like to be in the audience for a Johnny Cash show in 1968.’

“Featuring Cash entirely on the right channel and the Tennessee Three all on the left - a decision even Starfinder Stanley, Owsley's son, admits is ‘a bit weird until your brain adjusts’ - he sets the listener right between Johnny and his band, as if they were center stage at the Carousel that evening. It's a testament to the unconventional genius of a sonic innovator whose avant-garde techniques are accepted as gospel today.”

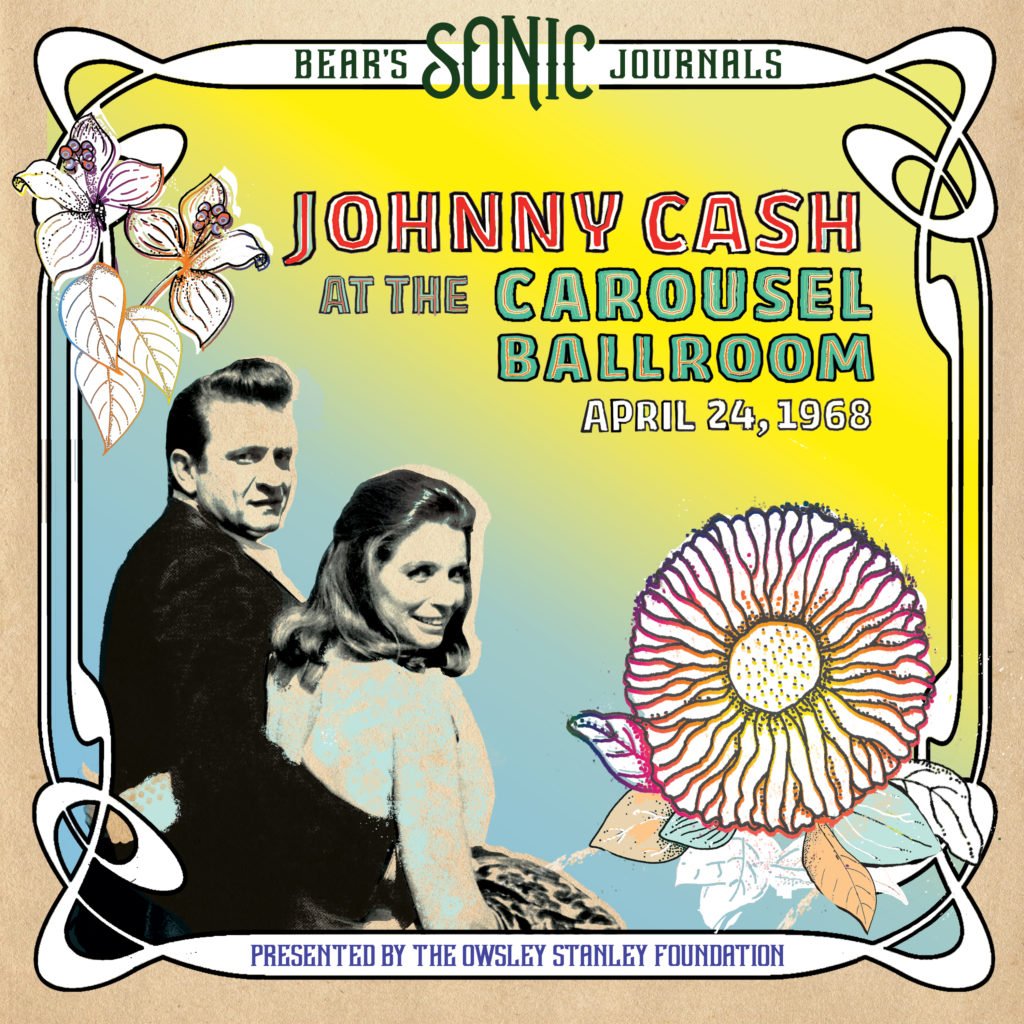

Johnny Cash At The Carousel Ballroom out on all digital formats by Legacy Recordings, the catalog division of Sony Music Entertainment, is now available on CD and this week issued as a 2LP from Renew Records/BMG on December 3rd.

It has new essays by Johnny and June Carter Cash’s son John Carter Cash, Starfinder Stanley, the Grateful Dead’s Bob Weir, and Widespread Panic’s Dave Schools, as well as new art by Susan Archie, and a reproduction of the original Carousel Ballroom concert poster by Steve Catron. It’s a collaboration of the Owsley Stanley Foundation and BMG.

This release marks the latest entry in the Owsley Stanley Foundation’s ‘Bear’s Sonic Journals’ series, which has previously included Stanley’s live recordings of the Allman Brothers Band, Tim Buckley, Doc & Merle Watson and many more.

I’ve heard anecdotes from some attendees about this Johnny Cash booking for over a half a century.

Johnny’s life was on the rise, although it wasn’t entirely obvious—yet. He’d just married the love of his life, June Carter. He had temporarily conquered his drug problems. In just two weeks, Columbia Records would ship to rack jobbers, retail outlets and disc jockeys Johnny Cash at Folsom Prison. The next year he’d command an ABC-TV show, which helped him become an American icon.

But on April 24, 1968, his career was in transition, which meant that when he got an offer to tack a last-second gig onto the end of his tour at a hippie ballroom in San Francisco, he took it. Mother Maybelle and the sisters had already gone home; it was just John, June, and the Tennessee Three booked in front of an estimated 700 people at the Carousel Ballroom on a Wednesday night.

Since it was a slightly different room and audience, Cash felt free to vary things. In addition to all his usual songs, he covered two Dylan songs (“Don’t Think Twice,” “One Too Many Mornings”) and one of his greatest but less frequently performed songs, “The Ballad of Ira Hayes.”

And Bear taped every note. The Carousel Ballroom’s resident sound man and recording whiz, Owsley Stanley, recorded the show in a way, says his son that makes you “feel as though you’re on the stage.”

Earlier, country music legends, Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs and the Foggy Mountain Boys on November 30, 1967 found themselves playing along to a psychedelic light show at The Avalon Ballroom in San Francisco.

Earlier, country music legends, Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs and the Foggy Mountain Boys on November 30, 1967 found themselves playing along to a psychedelic light show at The Avalon Ballroom in San Francisco.

In 1966, Johnny Cash was just concluding his own geographical relationship to the Southern California area. Before he became a living tradition, Johnny Cash spent large portions of a decade of his life near Los Angeles and Hollywood after leaving Sun Records and Memphis, doing his first gospel LP when he signed to Columbia Records.

On August 13, 1957 at a party in California, Cash first met British-born record producer Don Law after a local television date who first touted Johnny about joining Columbia Records after Cash’s contract with Sam Phillips and Sun ended on August 1, 1958.

In August 1958 Cash and clan moved to California and he rented an apartment on Coldwater Canyon Avenue in North Hollywood.

Cash and his family later bought a ranch house from comedian/TV host Johnny Carson on Havenhurst Avenue in Encino in the San Fernando Valley. Johnny Cash Enterprises was located on Sunset Blvd. at the Crossroads of the World complex in Hollywood.

Johnny did a slew of television appearances in the Southern California area in the sixties including the Compton-based and Hadley’s Furniture sponsored Town Hall Party program in 1960 that was broadcast on KTTV-TV.

In 1961 Johnny came to Pal Records on Sherman Way in Canoga Park for an autograph party.

Cash, and his pal, actor, singer and radio host, Johnny Western, along with Pat Shields, a PR guy doing promotions for Liberty Records, formed a company together called Great Western Enterprises on Western Avenue in Hollywood.

In 1964 Cash recorded Bitter Tears: Ballads of the American Indian, his history of Native Americans concept album. Cash sent out personal letters and copies of his 45RPM recording of folksinger Peter La Farge’s “The Ballad of Ira Hayes” on that album, after Johnny purchased a thousand of them from Columbia Records and mailed the entire batch to every radio station in the country. It eventually landed at number three on the Billboard Country Singles chart in 1964.

In February 1965, Cash performed “The Ballad of Ira Hayes” on a Los Angeles television program, The Les Crane Show. Cash and group would perform the song on April 24, 1968 in San Francisco.

During 1965 I saw Cash on Shindig!, taped on Prospect Ave. in Los Angeles at ABC-TV studios, and in 1968 when he guested on The Summer Smothers Brothers Show at CBS Television City.

Around this time I found out that Johnny Cash and had the same February 26th birthday. I later caught Johnny and June Carter Cash at The Anaheim Convention Center, The Troubadour and The House of Blues in West Hollywood. I saw their act over a dozen times.

June Carter Cash was always a big part of Johnny's life. Together they are the king and queen of country music. June Carter, long before her billing with Johnny, played guitar and sang on Nashville's Grand Ole Opry for 17 years. She appeared with Johnny on stage since 1961. And with this Owsley "Bear" Stanley recorded Carousel show you hear her vocals, guitar work and the sweet harmonies she shares with Johnny.

When John R. Cash died in 2003, music journalist Todd Everett informed me about a 1964 Ventura College Gymnasium benefit Cash did for the local police department, “‘cause Johnny was always getting in trouble in an area between Ventura County and Ojai California. His young girls with his first wife Vivian (Liberto) grew up there. And Johnny purchased his father a trailer home. And if that ain’t country you can kiss my ass.”

On August 16, 1975 forty miles from Los Angeles, California, I interviewed Johnny Cash for the now defunct Melody Maker inside the Royal Inn Hotel in Anaheim. Johnny was in Southern California in 1975 to promote his autobiography, Man In Black, and to perform a special concert for the Christian Booksellers convention.

I spoke with Johnny about the new popularity of country music. Cash and other country music stars now headlined bigger venues and their records were heard more frequently on both the AM and FM radio dial.

"One reason country music has expanded the way it has is that we haven't let ourselves become locked into any category. We do what we feel,” reinforced Cash.

“I like to go into the studio with my own musicians and record my own songs,” underscored Johnny. “I’m open to other songwriters. I like to do things different all my career.”

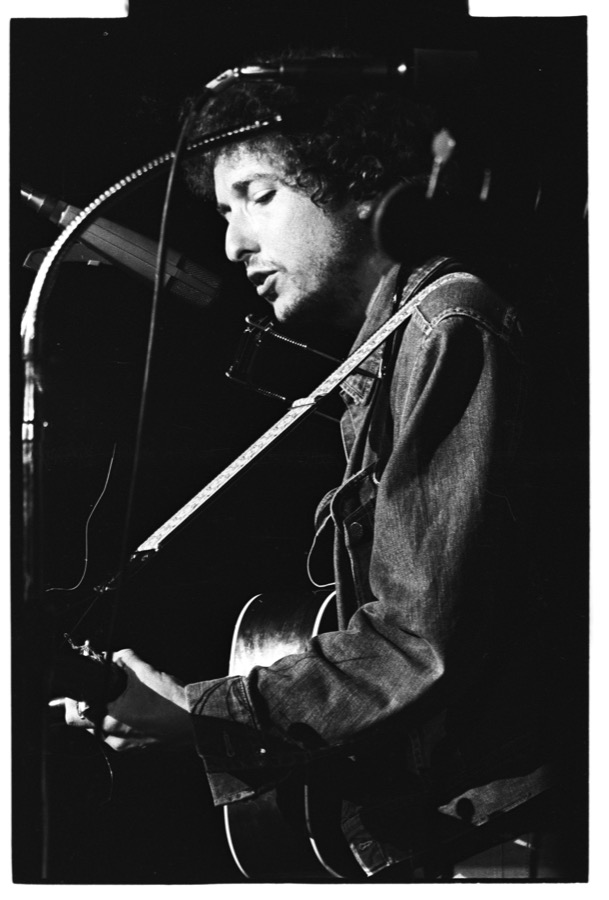

At his landmark Carousel Ballroom ’68 appearance, Cash felt free to vary things in his repertoire. In addition to all his usual songs, he sang two Bob Dylan songs, “Don’t Think Twice,” and “One Too Many Mornings.”

In our 1975 conversation, I asked Johnny about Dylan.

"I became aware of Bob Dylan when the Freewheelin' album came out in 1963. “I thought he was one of the best country singers I had ever heard. I always felt a lot in common with him. I knew a lot about him before we had ever met. I knew he had heard and listened to country music. I heard a lot of inflections from country artists I was familiar with. I was in Las Vegas in '63 and '64 and wrote him a letter telling him how much I liked his work. I got a letter back and we developed a correspondence.

"We finally met at Newport in 1964. It was like we were two old friends. There was none of this standing back, trying to figure each other out. He's unique and original. I keep lookin' around as we pass the middle of the 70s and I don't see anybody come close to Bob Dylan. I respect him. Dylan is a few years younger than I am but we share a bond that hasn't diminished. I get inspiration from him."

As a teenager, in the very late fifties, Dylan, birth name Robert Allen Zimmerman, hitchhiked from Hibbing, Minnesota, to Duluth to see Cash and the Tennessee Two (Marshall Grant bass and Luther Perkins guitar) play at the Duluth amphitheater.

In the revealing 2009 book A Heartbeat And A Guitar Johnny Cash and the Making of Bitter Tears by author Antonino D’Ambrosio, Johnny Western disclosed to D’Ambrosio in an interview witnessing a Dylan and Cash exchange where Dylan admitted, “Man, I didn’t just dig you; I breathed you.”

In November 1961, Cash had stuck his head inside the Columbia Records studio when talent scout/A&R man John Hammond was producing Dylan’s debut long player, Bob Dylan.

“Dylan was also grateful that Cash would constantly endorse his talents to skeptical Columbia Records executives,” Antonino expressed to me in a 2009 interview, “after the initial weak sales of his first platter, some calling it ‘Hammond’s folly,’ a jab at Hammond who signed Dylan to the label.”

Drummer and friend Jim Keltner on November 19, 1979 invited Knack drummer Bruce Gary and I to the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium to attend Bob Dylan’s Slow Train Coming tour. Jimmy arranged our tickets and backstage passes. I was reviewing the concert for Melody Maker, too.

I had a very brief chat with Dylan. We had met earlier at Gold Star studios when he was producing a session with Clydie King and I was on a few May ’79 dates as a percussionist with Keltner on the Phil Spector-produced Ramones’ album End of the Century.

Bob inquired about Phil. I told him I had recently done an interview with Spector for Melody Maker. Phil talked about R&B vocalists, also listing Dion, John, Paul, Elvis, Bobby Darin and Johnny Cash as great singers.

Dylan then removed his sunglasses. He has blue eyes like Eva Marie Saint, Charles Bukowski, and Kris Kristofferson. Bob offered a firm handshake, and sternly said, “Johnny Cash is a friend of mine.”

On February 6, 2015 Bob Dylan was honored at the 25th anniversary MusiCares 2015 Person of the Year Gala at the Los Angeles Convention Center in Los Angeles.

In his stage remarks, Dylan praised Cash.

"Johnny Cash recorded some of my songs early on, too. I met him about '63, when he was all skin and bones. He traveled long, he traveled hard, but he was a hero of mine. I heard many of his songs growing up. I knew them better than I knew my own. 'Big River,' 'I Walk the Line.' 'How High's the Water, Mama?’ I wrote 'It's Alright Ma (I'm Only Bleeding)' with that song reverberating inside my head.

"Johnny was an intense character, and he saw that people were putting me down [for] playing electric music. And he posted letters to magazines, scolding people, telling them to 'shut up and let him sing.' In Johnny Cash's world of hardcore Southern drama, that kind of thing didn't exist. Nobody told anybody what to sing or what not to sing."

“Bob has told me time and again how much he loved John’s music and his failure to compromise,” stressed Robert Hilburn, author JOHNNY CASH: The Life, in an interview.

“The bond was so great between them, even though they didn’t spend a lot of time together. Their relationship was more one of mutual inspiration and respect than time spent in each other’s company. Johnny Cash wasn’t about simply entertainment. Like Bob Dylan, he belongs with the great American artists, whether they are from the worlds of art, film or music. He told about his life and times with a strong, personal vision.”

Johnny Cash At The Carousel Ballroom is a remarkable sonic experience. It’s both companion and distant cousin to the Cash albums Bob Johnston produced.

In June 1967 Columbia Records staff producer Johnston replaced Don Law at the Nashville based company producing Cash. Johnston’s production acumen and label machinations on behalf of Cash in the 1968 and ’69 time period resulted in two California penitentiary location-created live recordings: Johnny Cash at San Quentin and Johnny Cash At Folsom Prison.

Johnston’s credits include Leonard Cohen’s Songs From a Room and Songs of Love and Hate, and Bob Dylan’s Highway 61 Revisited, Blonde On Blonde, John Wesley Harding, and Nashville Skyline. He worked on Simon & Garfunkel’s Bookends.

Johnston was born in 1932 in Hillsboro, Texas. His career began as a songwriter eventually holding a staff writing position at Elvis Presley’s Hill & Range Music and often reviewed potential Presley demos and songs earmarked for his movies in 1964 and 1965. Bob co-wrote with Charlie Daniels “It Hurts Me,” the flipside of Presley’s hit “Kissin Cousins” before he joined Columbia Records in 1965.

I met Johnston and producer/label executive Jimmy Bowen in July 1978 at MCA Records on Lankershim Boulevard in Universal City when I was West Coast Director of A&R for the label. At the time Johnston was producing Joe Ely’s Down on the Drag. We went down the street to see Ely at the Palomino Club.

“When I took over Cash he didn’t hit the country charts,” declared Johnston in a 2007 interview with me. “Like I said on the back of the Folsom Prison album liner notes, no one for eight years would let him go there to record live until he got me, and I said, ‘let’s do it.’ I picked up the phone and called Folsom and San Quentin,” Bob remembered.

“The reason the Folsom album was made first is because the Folsom warden answered first, simple as that. I got the warden, Duffy, and I handed Johnny the telephone and left. When we did Folsom there was a guy who was going to introduce Johnny on stage in front of the cons and everyone standing up.

“I said ‘bullshit!’ And told Johnny to go walk out there now! They are not even sitting down good. Walk out there and jerk your head around and say, ‘Hello. I’m Johnny Cash’ and it don’t matter what the fuck you record. And he said ‘Get outta my goddamn way!’ And he didn’t usually cuss. But he pushed people away went out there and the goddamn place became unglued!

“I had the engineer Neil Wilburn, did the Cash Live At Folsom Prison album with him. And he was a genius behind all that shit. I had a great thing with anybody who was a genius!

“Leonard was the best I’d ever heard. And Dylan was the best I’d ever heard. Simon was the best I’d ever heard and Cash was the best I’d ever heard. And all those fuckin’ people were the best I’d ever heard.

“I’ll tell you something else I did recording Dylan, Cash and Cohen,” emphasized Johnston. “Everybody else (at the time) was using one microphone. What I did was put a bunch of microphones all over the room and up on the ceiling. I would use the echo. I could do that as much as I wanted. I wanted it to sound better than anything else sounded ever, and I wanted it to be where everybody could hear it. And that’s the way that we did it. I always had four or eight speakers all over the room and I had ‘em going. The louder I played it the better it sounded to me.

“I had Cash in the Columbia Music Row studio [February 1969] and thought it would be nice to get Dylan in there, too and I didn’t say anything to them. Cash was in the studio and Dylan came in. ‘What are you doing here?’ ‘Gonna record.’ ‘Well, I’m recording too.’

“So, they invited me to dinner, but I said ‘no thanks.’ And when they returned I had a café set up outside with microphones and their guitars, and they came in for two hours, like a nightclub, looked at the lights, sorta smiled at each other. June Carter Cash was there. We did like 18 tracks.”

This authorized collaboration from Johnston, Cash and Dylan were finally heard 50 years later when Dylan and Legacy Recordings issued The Bootleg Series Vol. 15: Travelin’ Thru, 1967-1969.

Harvey Kubernik is the author of 20 books. Sterling/Barnes and Noble in 2018 published Harvey and Kenneth Kubernik’s The Story Of The Band: From Big Pink To The Last Waltz. For November 23, 2021 the duo has written Jimi Hendrix: Voodoo Child for the same publisher.

Otherworld Cottage Industries in 2020 published Harvey’s book, Docs That Rock, Music That Matters. His writings are in several book anthologies, most notably The Rolling Stone Book Of The Beats and Drinking With Bukowski.

This century Kubernik wrote liner notes to CD re-releases of Carole King’s Tapestry, Allen Ginsberg’s Kaddish, Elvis Presley The ’68 Comeback Special and The Ramones’ End of the Century.

For Record Store Day Black Friday November 2021, Kubernik penned the liner notes to Combination of the Two: Live at the Monterey International Pop Festival Big Brother and the Holding Company (featuring Janis Joplin).