On April 30, 2021, Rhino Records released Dave’s Picks Volume 38, a three-CD live album by the Grateful Dead. It contains the complete concert of their set recorded on September 8, 1973, at the Nassau Coliseum venue in Uniondale, New York.

A slew of seven previously complete Grateful Dead concerts from St. Louis is also being readied. Recorded on: December 9 and 10, 1971 at the Fox Theatre; October 17-19, 1972 at the Fox Theatre; and October 29 and 30, 1973 at Kiel Auditorium.

A press release describes the St. Louis birthed products.

“LISTEN TO THE RIVER: ST. LOUIS ’71 ’72 ’73 is available now for pre-order and will be released on October 1. Production of the set is limited to 13,000 individually numbered copies and available exclusively from Dead.net for $199.98. The collection will also be available in its entirety as a digital download exclusively at Dead.net in Apple Lossless ($139.98) and FLAC 192/24 ($174.98).

“Dead.net will also exclusively release LIGHT INTO ASHES: FOX THEATRE, ST. LOUIS, MO (10/18/72) as a double-LP on 180-gram custom vinyl for $44.98. Limited to 7,200 copies, the set features an exceptional hour-plus jam plucked from the Grateful Dead’s October 18, 1972, show at the Fox.

“On the same day, the December 10, 1971, Fox Theatre show from the boxed set will be released individually on CD, LP, and digitally at traditional retail outlets. FOX THEATRE, ST. LOUIS, MO (12/10/71) will be available as a 3-CD set ($34.98), a 5-LP limited edition on 180-gram vinyl (12,000 copies, $119.98) and digitally.

“LISTEN TO THE RIVER: ST. LOUIS ’71 ’72 ’73 comes in a slipcase with artwork designed by Liane Plant and features an 84-page hardbound book as well as other Dead surprises. To set the stage for the music, the liner notes provide several essays about the shows, including one by Sam Cutler, the band’s tour manager during that era, and another by Grateful Dead scholar Nicholas G. Meriwether, among others.

“The two 1971 shows feature the original Grateful Dead lineup of Jerry Garcia, Bill Kreutzmann, Phil Lesh, Ron “Pigpen” McKernan, Bob Weir, and newcomer Keith Godchaux on the piano. This version of the band would hold together for the next six months as the Dead embarked upon its Europe ’72 tour.

“By the time the Dead returned to the Fox Theatre less than a year later, they were without Pigpen, who’d played his final show with the Dead at the Hollywood Bowl on June 17, 1972. A year after the exceptional Fox 1972 shows, the Dead came back to St. Louis, but played the much larger Kiel Auditorium, touring behind the release of Wake Of The Flood, which came out just two weeks before the Kiel shows.”

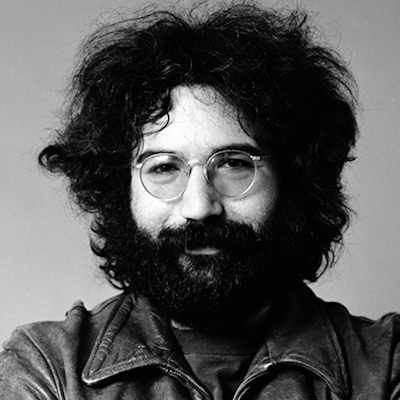

In related news, co-producers Jerry Garcia Music Arts LLC with Malcolm Leo and Dean Loring Gelfand of Malcolm Leo Productions are slated to release an immersive film experience focusing on the creative aspects of Jerry Garcia’s journey.

Jerry Garcia, Artist is a documentary based on an interview Malcolm Leo conducted and directed in 1987 filmed at Front Street Studio in San Rafael, California, by the Academy Award-winning cinematographer Russell Carpenter.

Garcia speaks directly to his audience about his music and art. Garcia's family is involved in the venture and co-producing the documentary. They’ve supplied visual art and music to the project. The documentary will have a charitable component that will benefit the Jerry Garcia Foundation and a charity chosen by the co-producer.

I conducted a two-hour interview in 1976 with Jerry Garcia, Bill Graham and Carlos Santana for the now defunct Melody Maker at music promoter/producer Graham’s house in Mill Valley, CA.

When I did this interview, I was not a collector of their records or a Dead head, and had only seen them a handful of times in the early and mid-70s. I enjoyed Jerry Garcia’s solo shows, especially his 1973 Ash Grove club date in Los Angeles.

I spent a few hours with Jerry Garcia. He was so accessible and interested in me as well and wanted to know who I dug, which books I had read and any comic books I collected.

I only had a few Grateful Dead albums and told him. I wasn’t a taper and didn’t swap cassettes of their gigs. Jerry grooved on my honesty. Periodically everyone around us would split, eat, smoke weed, move their wheels, but Garcia and I just jammed, akin to the way he played music with the Grateful Dead or anyone in his orbit.

Before we chatted we briefly talked about the Acid Tests in the Watts area of Los Angeles in summer, 1965. Garcia really grinned when I complemented him on his pedal steel playing and work on Jefferson Airplane’s Surrealistic Pillow LP.

I liked Bill Graham. Around his concert promotions he was hectic and frantic in motion. At his pad it was a mellow scene as we noshed on delicatessen food.

It originally was Graham and I, and then Garcia arrived, followed by Carlos, who also had to unwind with a game of tennis. Bill split for a while, to work the phone, what else is new, and basically Jerry and I just hung for a couple of hours. We chatted about poetry, the San Francisco beat scene, Jack Kerouac and the 1969 Woodstock music festival.

“I met Jerry in 1965. He was doing the acid tests,” remembered Bill Graham. “I thought he and his entire band were from another planet. I was very disturbed at those first parties because—and there’s a lot of differences in opinion—grown-ups as well as kids were testing their metabolism. I was producing theater in San Francisco at that time, where the group was still the Warlocks, doing benefits involving these groups. I got to know him later on.

“There is something that they’re always had in common from the beginning, something hardly spoken about in the media after all these years,” stressed Bill.

“The San Francisco bands, starting with the Dead, always went to the gigs with the intention of putting it out there. It was the lack of professionalism at the beginning that made that possible. It wasn’t that the contract said 45 minutes and ‘that’s what we’ve got to play.’ They were the first one who asked to play longer. They wanted to extend the relationship between the audience and themselves. And that prevails to this day. You can’t get them to play shorter sets. Carlos always wanted to play longer which is very different from the professional attitude that you get.

“One of the reasons for that—and Jerry won’t say it—is you get a man like this who can make all kinds of money across the country. The Grateful Dead just came off the road, and he has a desire to play, and he takes his band and plays a club that holds 400 people! When you go out, you want to make music and you want to make a living. There are times when I really think the Grateful Dead are demented. Insane. They could have made ten times as much money.”

Harvey Kubernik and Jerry Garcia Interview

HK: You and the band have helped create an ongoing music community and scene.

JG: I really think the scene out here created the possibility for Woodstock to happen. The Monterey International Pop Festival. The thing, the activity, music and people. The set-up was out here.

HK: Jerry, in a business marked by one-hit wonders and trends, how do you account for your longevity?

JG: We’re serious. One of the things you could say about all the bands that came from San Francisco at that period of time was that none of them were very much alike. I think each of us has dealt with it in various ways. Like, Carlos has developed himself into a spiritual being from a completely different kind of person. For me, I know what I’m supposed to do, and I’ll do what I’ll have to do to be able to play. I think almost all the people I’ve known around this area, involved around the music scene, have been faithful to that thing.

HK: Was there any added pressure being a mouthpiece for the community?

JG: Everybody knows who they are. No matter what you read about you in the paper, you know who you are. You don’t get any special breaks at the gas station. You can either be sucked in by that stuff, in which case it just eats you or else just realize there’s a difference between what you read and who you are.

HK: Didn’t you ever feel you represented something special to the honest music community?

JG: I always did. I think that the world has changed. I think the United States has changed very visibly in the last ten years. A lot of it had to do with what happened in San Francisco. I can’t say how or why, but I also think it’s affected everything?

HK: Like how?

JG: Just all the interest in things like ecology. All the interest in the sense of personal freedom as expressed by all kinds of movements. All these things were designed to free the human. Social overtones. All that stuff. The communal spirit.

HK: Have you always liked playing live? You strike me as a workaholic.

JG: I like the live experience. That’s where it counts. That’s when music is real. It’s real in that situation. That’s the situation that I feel I have the greatest sense of personal responsibility about. I don’t mind putting out a bad record, but I really hate a bad concert. That really is depressing.

HK: You get into other musical avenues with solo projects away from the Grateful Dead. Has there ever been any conflict or compromise in doing a tune for the Dead or keeping it for future solo endeavors?

JG: It’s not judgmental. You can’t deal with it in a yes/no kind of fashion. For example, my band is a band that could best be described as consonance and harmony. Conceptually, everybody in the band thinks pretty similarity. In the Grateful Dead it’s a situation in which almost no two people have the same conception musically; which makes it harder. Nobody gets their way. However, what we all respect about that situation is that there is a potential of a larger central viewpoint which none of us, individually, are capable of perceiving, but which we all add to because of the diversity and the conflict.

HK: Did you ever think ten years ago that the Grateful Dead would get beyond the ballroom circuit and that rock and roll would be presented in baseball stadiums?

JG: When the Acid Tests were happening, I personally felt “In three months from now the whole world will be involved in this.” So as far as I’m concerned, it’s been slow and disappointing. Why isn’t this paradise already?(laughs). My personal feeling has been one of waiting around.

HK: Being an elder statesman in the rock and roll world, how long do you feel you can continue the hectic pace, touring deadlines?

JG: I’ve learned that it requires a certain discipline for me personally. And I know I’ll approach it in a certain way. I’ll definitely burn out, and I wouldn’t survive a tour, for example. For me, it’s a matter of surviving. This is the set of givens. You’re gonna be in airports, motels, exposed to any number of strange drugs, strange experiences, intensity of this sort, and so forth.

Within that framework how do you stay even? What you do is learn, so it becomes a thing of pace, vitamin C, protein. You try and stay alive. That’s a fundamental problem. I’m just the sort of person who deals with things on that level. Once I know things what I have to cope with, it’s just a matter of adjustment. I just hate personal failure, being on stage and going through the changes and playing bad because I’m either not well, tired, too stoned, whatever. To me it’s an aversion therapy thing. It’s the reason I’ve been able to survive.

HK: You, Bill Graham and Carlos are cultural heroes of the Bay area scene. Was there any added pressure being a mouthpiece for the community?

JG: Everybody knows who they are. No matter what you read about you in the paper, you know who you are. You don’t get any special breaks at the gas station. You can either be sucked in by that stuff, in which case it just eats you or else just realize there’s a difference between what you read and who you are.

HK: Jerry, do you have high and low points that you best remember looking back over the last ten years?

JG: Well, I can get into that real easy. The worst for use and for me personally was Woodstock. The ultimate calamity. First of all, we were really stupid in the way we dealt with it. It was raining and we went on just after it got dark. There was maximum confusion going on, sound logistics. Really weird. Plus I was high, of course. And I went on stage in a state of confusion. Huge crowds of people over the stage. The stage had sheet metal and stuff on it, it’s wet, and I’m getting incredible shocks from my guitar.

Pretty soon I started hallucinating ball of electricity rolling across the stage jumping off my guitar. Meanwhile, all the little citizen band radios and walkie talkies and things with the amplifiers so there’s weird voices coming out of the amplifiers. It’s dark, and you don’t see any audience, but you know there are 400,000 people out there.

Then somebody leans over across the stage, since everyone is ganged up and says the stage is about to collapse. I’m standing there in the middle of this trying to play music. Then they turn on the lights, and the lights are a mile away. Monster super troopers. Totally blinding, and you can’t see anything at all. Here’s this energy and everything is horribly out of tune, ‘cause it’s all wet, damp and humid. It was just a disaster. It was humbling (laughs).

Harvey Kubernik is the author of 19 books, including Leonard Cohen: Everybody Knows published in 2014 and now available in six foreign language editions. Kubernik also authored Canyon Of Dreams: The Magic And The Music Of Laurel Canyon and Turn Up The Radio! Rock, Pop and Roll In Los Angeles 1956-1972.

Sterling/Barnes and Noble in 2018 published Harvey and Kenneth Kubernik’s The Story Of The Band: From Big Pink To The Last Waltz. For October 2021 the duo has written a multi-narrative volume Jimi Hendrix: Voodoo Child for Sterling/Barnes and Noble.

Otherworld Cottage Industries in 2020 published Harvey’s book, Docs That Rock, Music That Matters, featuring interviews with D.A. Pennebaker, Chris Hegedus, Albert Maysles, Murray Lerner, Morgan Neville, Dr. James Cushing, Curtis Hanson, Michael Lindsay-Hogg, Andrew Loog Oldham, Dick Clark, Ray Manzarek, John Densmore, Robby Krieger, Travis Pike, Allan Arkush, and David Leaf, among others.

Kubernik’s writings are in several book anthologies, most notably The Rolling Stone Book Of The Beats and Drinking With Bukowski.

This century Harvey wrote the liner note booklets to the CD re-releases of Carole King’s Tapestry, Allen Ginsberg’s Kaddish, Elvis Presley The ’68 Comeback Special and The Ramones’ End of the Century. Kubernik is the Project Coordinator of The Jack Kerouac Collection, a box set of recordings.

In November 2006, Harvey was a speaker discussing audiotape preservation and archiving at special hearings called by The Library of Congress and held in Hollywood, California.

During 2020 Harvey Kubernik served as a Consultant on the 2-part documentary Laurel Canyon: A Place in Time directed by Alison Ellwood. Kubernik recently worked on a documentary about Rock and Roll Hall of Fame member singer/songwriter and producer Del Shannon.

Kubernik also appears as a screen interview subject for director/producer Neil Norman’s GNP Crescendo documentary, The Seeds: Pushin’ Too Hard. Jan Savage and Daryl Hooper original members of the Seeds participated along with Bruce Johnston of the Beach Boys, Iggy Pop, Kim Fowley, Jim Salzer, the Bangles, photographer Ed Caraeff, Mark Weitz of the Strawberry Alarm Clock and Johnny Echols of Love. Miss Pamela Des Barres supplied the narration. The documentary is scheduled for broadcast TV screening during 2021.

This decade Harvey was filmed for the current in-production documentary about Hollywood landmark Gold Star Recording Studio and co-owner/engineer Stan Ross produced and directed by Brad Ross and Jonathan Rosenberg. Brian Wilson, Herb Alpert, Richie Furay, Darlene Love, Mike Curb, Chris Montez, Bill Medley, Don Randi, Hal Blaine, Shel Talmy, Don Peake, Slim Jim Phantom, Kim Fowley, Johnny Echols, Gloria Jones, Carol Kaye, Marky Ramone, David Kessel and Steven Van Zandt have been lensed.