“Small miracles brought us here.” - Holly Prado

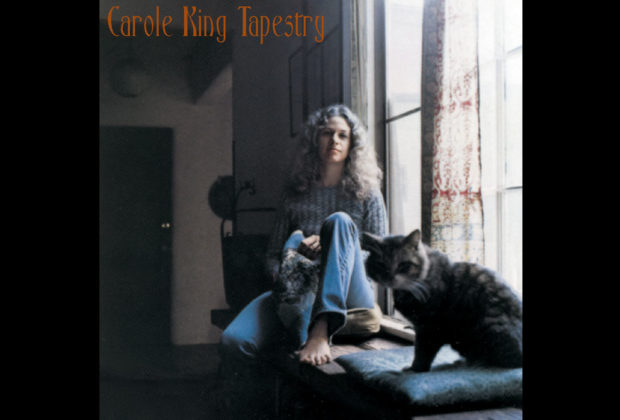

The 1971 legendary Tapestry album released on February 10, 1971 from singer/songwriter and pianist Carole King was produced by Lou Adler and engineered by Hank Cicalo at A&M Studios in Hollywood.

The LP spent 15 weeks at No. 1 in spring of 1971. It garnered four Grammy Awards, including Album of the Year, Best Pop Vocal Performance (Female) Record of the Year, “It’s Too Late;” and Song of the Year “You’ve Got a Friend” at the 1972 Grammy Awards. Producer Quincy Jones was a 1972 Grammy recepient for an arrangement on his own LP of King’s “Smackwater Jack.” The album resided fulltime on the music record charts for six years, generating over 24 million in sales worldwide, making it one of the most successful discs of all-time.

In 2003, as yet another milestone of its importance, Tapestry was one of 50 recordings selected by the Library of Congress and placed in the National Recording review.

“Rare is that album that defines its era in pop music. Tapestry was just that in 1971. And a half-century later, it is still the gold standard for singer/songwriters,” lauded Prof. David Leaf of the UCLA Herb Alpert School of Music.

Recording artist/actress Reba McEntire also cited the title. “I had Tapestry like everyone else in the world did, and it was a huge influence on me.”

Carole King in a 2008 Epic/Ode/Legacy Records communication commented about Tapestry. "I feel honored that ‘Tapestry’ has made a difference in small ways and large ways in people's lives around the world. It's been a major part of my life, too," she adds. "As a songwriter, I'm so happy that the songs have held up for all of these years. As a performer, I'm still enjoying playing them live, most recently on my Living Room Tour."

During 2008 King’s Tapestry was reased with a second CD of her live performances in retail outlets on the Epic/Ode/Legacy record label, a division of Sony BMG Music Entertainment. I wrote the 5,000 word liner note booklet for this Tapestry deluxe edition. In 2010 Andrew Loog Oldham and I penned the joint liner note essays to The Essential Carole King for the same label. It’s a collection of some tracks from Tapestry coupled with her recording career compositions (co-written with Gerry Goffin, among others).

In 2010 I served as Consulting Producer on the 2010 singer-songwriter documentary, Troubadours directed by Morgan Neville chronicling the musical expedition of Carole King and James Taylor. The film was shown at the 2011 Sundance Film Festival in the documentary category. In March 2011, PBS-TV broadcast the movie in their American Masters series.

Tapestry arrived in early 1971 with little fanfare and modest expectations. Fifty years later it holds an exhalted place in the pantheon of pop music; a triumph of master craftsmanship married to a feminine sensibility that transformed both its audience and the marketplace.

Tapestry breathes its eternal life as an album constructed of musical monologues and melodies of infinite possibility and unchallengable fate. There was a use of jazz in the way the songs were constructed, and the nuance of the singing. King’s vocals are marvelously suggestive. Tapestry remains just mellow enough to be confortable and just as exciting enough to be engaging. Tapestry documented a Hollywood community developed at the A&M studio environs on the corner of Sunset Blvd. and La Brea Ave. It’s about the city as an ongoing dream and a region that King invented out of her relationships.

Music reviewer Robert Hilburn, in the Los Angeles Times on April 25, 1971, stated that the themes were “Expressions of love, friendship, [and] home on such songs as ‘Where You Lead,’ ‘Home Again,’ and ‘So Far Away.’ As a writer, pianist, and vocalist Ms. King is a bright new record talent.”

“Tapestry was a # 1 album in Canada,” Larry LeBlanc, Canadian editor of Record World from 1970-1980,” wrote to me in a 2020 email.

“A&M Records in Canada had just opened a year before and had a young team and kicked ass on the album. I also had close ties and a bond with Gerry Lacoursiere, who was president of A&M Canada, who was brought in from the United States where he worked for Decca and Liberty out of Detroit and Atlanta. As with the United States, the Tapestry tracks hit the ‘sweet spot’ being major events for both AM radio and FM radio.

“Carole's Writer had picked up substantial interest on release in Canada, more so when she landed in Toronto unannounced as the opener for James Taylor at Massey Hall. I came across her by accident backstage when I was visiting James whom I knew via Joni Mitchell. There was a damn good bootleg of Carole floating around that has her hits and songs from Writer and maybe a few from Tapestry on it.”

King’s 1970 Writer and ’71 Tapestry inspired consumers, non-performers, and music business retail veterans like Carol Schofield who named her record label MsMusic Productions.

“When I worked at Wherehouse Records in San Francisco in the very early seventies I have fond memories of customers regularly buying Writer and then Tapestry. It was very different foot traffic than from a year earlier when a lot of LP purchases were the Beatles, Jimi Hendrix, Love, the Rolling Stones, Byrds, Jefferson Airplane, Grateful Dead and Doors.

“Writer and Tapestry are still revered. It’s timeless. Classic...Carol King is definitely a ground breaking female songwriter artist pioneer who rose above a traditional male dominated arena.”

In 1995 several music recording icons including Aretha Franklin, the Bee Gees and Rod Stewart covered the original tracks for a tribute album, Tapestry Revisited: A Tribute to Carole King.

During 1999, Lou Adler mentioned some reasons for the popularity and longevity of Tapestry to music journalist Matthew Greenwald in the Japanese periodical Record Collector.

“I think what she wrote, the songs, were not limited to a time. They're somewhat timeless love songs. I mean, those emotions have not gone away because of any change in technologyor space or any other reason. They're basic love songs, they're basic emotions. It's the same reason that it hit probably the first time around, it hits the same chords with the emotions that it deals with, and it works today. I'm not suprised at the longevity of Tapestry. I may have been somewhat suprised with the immense success of it at the time, because no album had sold so much. The amounts that we were shipping were staggering. But I'm not suprised with the longevity of its success. I think part of it goes back to the way it was recorded. It’s not something that's out of date - its rhythm-sounding instruments, its true sounding-instruments, and the emotions are still the emotions. She hit the chords.”

Lou Adler first met Carole King in 1961, when he helmed the Sunset Blvd. West Coast office for Aldon Music. King and Gerry Goffin, her poet/lyricist husband, were staff writers at that New York-based publishing company.

By 1968 Carole had evolved from the regional Brill Building cubicle world of writing on demand to writing for herself, not the charts. And that played neatly into the unfolding singer-songwriter renaissance. This former Brooklynite and 1966 West Orange New Jersey resident felt emancipated…and newly Laurel Canyon-ized.

Tapestry featured eight King solo compositions, three co-writes each with lyricists Gerry Goffin and two selections with Toni Stern. Adler’s subtle and deft studio prowess enhanced King’s musical and vocal abilities.

While Tapestry earned her superstar status, Carole King and Gerry Goffin had already firmly established themselves as one of pop music's most gifted and successful tunesmiths. Their songs had been recorded by everyone from the Beatles to Aretha Franklin.

Born Carole Joan Klein, Aquarius, on February 9, ’42, in Brooklyn, New York, King started learning piano at the age of four, and formed her first band, the vocal quartet the Co-sines, while in high school at Madison High School and graduated in 1958.

A fan of the composing and production team team of Jerry Lieber and Mike Stoller (the duo behind remarkable records with the Robins, the Coasters, Elvis Presley, the Drifters, Ben E. King), King became a fixture at exciting deejay Alan Freed's Rock 'n' Roll shows featuring the likes of Chuck Berry, Larry Williams, and the Everly Brothers.

While attending high school Carole met budding songwriters Neil Sedaka from Lincoln High and then later Paul Simon at Queens College as well as chemistry major/lyricist Gerry Goffin there, with whom she forged a writing partnership and became her future husband.

Sedaka helped the Co-sines get an audition with Atlantic Records’ Ahmet Ertegun, and simultaneously Jerry Wexler gave her an office meeting to hear her material. King cut a couple of records under her own name: For the Alpine label “Oh Neil,” a response to Neil Sedaka’s own hit “Oh Carole,” and “Short Mort,” a 45 RPM on RCA Victor.

Don Costa, then A&R at ABC-Paramount Records had King’s debut single, "The Right Girl" released on the label in May 1958. Sedaka as well introduced Carole King and Gerry Goffin to Don Kirshner, who helmed a publishing company, Aldon Music, with Al Nevins. King and Goffin then subsequently pacted with Nevins and Kirshner's Aldon Music at located at 1650 Broadway.

A decade of songwriting success followed, during which Goffin-King delivered a slew of memorable US and UK hits: "Will You Love Me Tomorrow" (Shirelles), "Some Kind Of Wonderful" (Drifters), "Halfway To Paradise" (Tony Orlando), "Every Breath I Take" (Gene Pitney), “Point Of No Return” (Gene McDaniels), "Take Good Care Of My Baby" (Bobby Vee), "), "The Loco-Motion" (Little Eva), "Up On the Roof" (Drifters), “Go Away Little Girl" (Steve Lawrence), "Don't Say Nothin' (Bad About My Baby)" (Cookies), "One Fine Day" (Chiffons), and the proclamation "Hey, Girl" (Freddie Scott). King also collaborated with Howie Greenfield on “Crying In the Rain," a terrific record that Lou Adler produced for the Everly Brothers while they were on a tour in Omaha, Nebraska.

Phil Spector recognized the literary scripture of Goffin and King producing a gem for the Righteous Brothers, "For Once In My Life."

John Lennon, Paul McCartney and Ringo Starr were self-proclaimed fans of Goffin and King while George Harrison sang the lead vocal on their “Chains.” Their “Don’t Ever Change,” earlier done by the Beatles in their Decca Records audition recording, was initially waxed by the Cricketts, and discovered via bootleg, and covered years later by Brinsley Schwarz and Byran Ferry. Mickie Most produced "I'm Into Somethin' Good" for Herman's Hermits and “Don’t Bring Me Down” by the Animals.

The Monkees did "Take a Giant Step" and "Pleasant Valley Sunday.” In 2008 producer Chip Douglas told me that when he heard the Goffin/King demo of “Pleasant Valley Sunday” and then prepared the arrangement for the Monkees version he got the bridge backwards and turned the ending of the song around resulting in a sonic wonder by Chip helping fashion a Top Ten entry for Carole and Gerry. Douglas informed me he saw King at the Screen Gems office in Hollywood after he cut “Pleasant Valley Sunday.” “She glared at me from a window across the room. Maybe because I changed a line and made it faster than the way she originally did it.”

King had a charming hit single herself with “It Might As Well Rain Until September” on the Aldon Music-birthed Dimension label which reached number 3 in the UK charts in 1962 and Top 30 in the US.

In a 2000 interview with me, I asked Al Kooper, keyboardist/singer/songwriter/producer and founder of Blood, Sweat & Tears about the Brill Building. Kooper started his illustrious career in 1957 playing guitar as a member of the Royal Teens who charted with “Short Shorts.” Kooper at the time was teaching at the Berklee School of Music in Boston, Massachusetts. In fall 2001, Berklee bestowed an honorary doctorate on Kooper and jazz great Elvin Jones in a ceremony.

“Music publisher Lee Silvers [who discovered Herb Alpert and Bobby Hart] was in 1650 Broadway. That’s where I got started. In his office! I became the guitarist for the Royal Teens. He signed me. Bob Gaudio (Four Seasons) and I were all underage. When I met Bob Gaudio he was 16 and I was 14.

“One thing I fight is the major revision of my life: Which is that they call it the Brill Building Sound and it never took place in the Brill Building,” explained multi-insrtumentalist and educator Kooper

“The Brill Building was always the Brill Building at 1619 Broadway. And it died about 1957. It was huge before that, the Frank Sinatra crowd. It had frosted glass doors, a beautiful, well-constructed building. And then, around 1958, ’59, 1650 Broadway got refinished, and they had black doors and cheaper rents. And everybody went there.

“There was another building, too, at 1697 Broadway, the building where the Ed Sullivan Theater is. And there were people in there too, but mostly R&B people. And 98 per cent of what they call the Brill Building Sound was done at 1650 Broadway,” Kooper underscored. “Don Kirshner ran Aldon Music on 51st Street in a music building at 1650 Broadway.

“You ask any person that writes about the Brill Building Sound, with the exception of Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller, Burt Bacharach, Jeff Barry and Ellie Greenwich, who were actually in the Brill Building. But here is who wasn’t in the Brill Building: Gerry Goffin and Carole King, Barry Mann and Cynthia Weil, Neil Sedaka and Howie Greenfield, Tony Orlando, Chuck Jackson, and Dionne Warwick. Bell Tone Records was there, Bobby Lewis and the Jive Five. All this music came out of 1650 Broadway and it was the young people’s place. The Brill Building was for old people,” underscored Kooper.

“It makes me sick historically when they call the songs Carole and Gerry wrote ‘the Brill Building sound’ because none of them were composed in that building! But I’m telling you this specific Brill Building history because it’s the bane of my existence. None of that music, with the exception of the people I mentioned, came from the Brill Building,” stressedAl.

Don Kirshner sold Aldon Music to Screen Gems publishing company in 1963.

In his column for New Music For Old People in 2014, Kooper penned a tribute to Gerry Goffin, who co-wrote two numbers with King on Tapestry, “Will You Love Me Tomorrow?” and “(You Make Me Feel Like) A Natural Woman” a Goffin/King and Jerry Wexler composition.

“Gerry Gofffin was born February 11, 1939 in Brooklyn, New York and grew up in Queens, not unlike myself. After graduating from Brooklyn Tech High School, he enlisted in the Marine Corps Reserve at the US Naval Academy. After a year he left the Navy to study chemistry at Queens College. It was there that he met Carole King and they began writing songs together. Within a couple of years, when Carole was 19 and Gerry was 22, they had written the #1 song in America in January 1961, ‘Will You Love Me Tomorrow’ by the Shirelles. This began an unrivaled chain of successes that continued for decades. They married in 1959 and divorced in 1968, but still wrote together occasionally. Gerry was a major influence on me as I was born in Brooklyn, raised in Queens, and we both worked as songwriters at 1650 Broadway in New York from 1959 to 1963. We never met until much later in life and instantly bonded; we wrote two songs together.”

Earlier this century Al conducted an interview with songwriter Gerry Goffin in Santa Monica, California about his legacy around the time they collaborated together. Kooper’s dialogue with Goffin can be heard on YouTube.

In 2007 I asked author Andrew Loog Oldham, who produced the Rolling Stones’ records 1964-1967 to reflect on the Goffin and King team and their “demonstration records” he acquired.

“But you see, they were like gold dust,” enthused Oldham. “Those demos, I remember -- To start with, the weight of the acetate and the weight of the playing, the suggestion of the playing. It was just the space that -- The amazing ability, still, to leave space that suggested what someone should -- I mean, Dusty Springfield should know.

“Lou Adler and I were part of the new breed of producers who participated in a different way with the artists we record. But what Carole, the songs of Carole and Gerry Goffin and with whomever she was writing served was that old -- in England, the Mitch Miller -- Well, not Mitch Miller, because he was an accomplished musician. But the model of where the producer, be it Johnny Franz with Dusty Springfield, they would give it to the arranger and see what he came up with.

“And so from the demo, the arranger did the parts, and the parts were there. I mean, when you heard -- It’s like the ability -- It’s actually the ability to sell. And we go back to like Tin Pan Alley and the people on the back of trucks, of flatbed trucks, playing -- selling the sheet music. This is the gift that then permeated its way through people like Jerry Herman and Alan Jay Lerner and the writers of those times. And because it was the same streets as The Sweet Smell of Success, there it was, on Broadway, in 1650 in Aldon --And that great gift, and the -- I mean, Mitch Murray with ‘How Do You Do It?’ didn’t quite have it. Yeah. I mean, John Lennon at a piano, that’s a different story.”

“The work that Carole did with Gerry in that Brill Building-Aldon Music pressure cooker made an artist out of her. You can't put a price on the discipline of working on demand and always looking over your shoulder to see if Barry Mann and Cynthia Weil or Jeff Barry and Ellie Greenwich are outdistancing you,” observed music journalist Kirk Silsbee

“Then, there was the artistic standard set for all of them by the writing and production of Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller. Theywere always three jumps ahead of the younger songwriting teams and they showed them the way. So Goffin-King got it from all sides. That was healthy competition and that kind of boot camp is something you can't put a price on. If you're a real songwriter, you'll only thrive in that kind of environment. That's true of any artistic field where you're forced to produce. You either rise to the occasion or you don't. If you don't, they get rid of you. When Don Kirshner sold the Aldon Music catalog to Screen Gems and Goffin-King started writing for the Monkees, the world changed,” suggested Silsbee.

“At their best, the Goffin and King songs have a classic quality that outlive the time in which they were introduced. ‘Will You Love Me Tomorrow’ is a question every woman has asked. Likewise, what woman hasn't wanted to feel like a ‘Natural Woman?’ And who doesn't need to get away and just be alone sometime, someplace like ‘Up on the Roof?’

“Musically, those songs were also very well-constructed,” stressed Silsbee. “They don't require apology on any level. We know that demos were an important part of the Brill Building process. They were, for that time and place, what sheet music and song pluggers had been to the Tin Pan Alley songwriters. Some demos were so good that they became hits and needed no revision: ‘Locomotion’ by Little Eva and the Jimmy Jones hits, ‘Good Timin'’ and ‘Handy Man.’ Carole sang on the demos of some of her own songs and, of course, she had hits like ‘It Might As Well Rain Until September.’ I always thought that she made up for any lack of studied vocal quality with feeling. And, of course, her phrasing was good because she knew how her songs should be sung.

“It's funny--a few of the Goffin-King hits, like the Shirelles doing ‘Will You Love Me Tomorrow’ and the Drifters on ‘Up on the Roof,’ were very pop-oriented, though they were cut by black groups. They were quite vanilla in contrast to what you might hear from some of the black artists of the day, like Don Gardner and Dee Dee Ford. Yet when Carole sang them ten years later, she added a degree of soul that hadn't been there before to what we knew of those songs. The Shirelles sang ‘Will You Love Me Tomorrow’ like girls. Carole sang it as a woman.

“A&M Records, where Tapestry was recorded, was a tremendously creative atmosphere, where it seemed like anything was possible,” he reinforced. “I've been told by people who worked there that there was an esprit de corps because that company was headed by a working musician. Then, there was the cachet of the A&M property, which had been Charlie Chaplin's studio. Along with that went the lore about ghosts on the lot,” concluded Kirk.

In 2020 I received an email from writer and author Richard Williams, an avid King and Brill Building fan.

“Maybe the first sign that Carole King was set to make a definitive break with her successful but semi-anonymous identity as a Brill Building hit-machine came with ‘The Road to Nowhere,’ a 1966 single full of drones, bells and angst which, despite being widely ignored, seemed to predict the coming sounds of both the Jefferson Airplane and the Velvet Underground. Three years later came Writer, an album that prefaced the era-defining Tapestry. As well as new compositions, Writer included songs already familiar from earlier versions by other artists: ‘No Easy Way Down’ (Dusty Springfield), ‘Goin’ Back’ (the Byrds) and ‘I Can’t Hear You No More’ (Betty Everett). King was letting us know that she was now ready to repossess her own material and step out into the world.

“Listen — and marvel. 1966! On the Dimension label in America and released in the UK on London American. I reviewed it for the Nottingham Guardian Journal. Blew me away. Somehow it seemed closer to ‘A Love Supreme’ than to ‘Will You Love Me Tomorrow.’”

In the mid-'60s she, Goffin, and entertainment music columnist and writer Al Aronowitz founded their own short-lived New Jersey-based record label, Tomorrow Records, briefly distributed by Atco Records. Charles Larkey, the bassist for the Tomorrow group the Myddle Class, eventually became King's second husband after her marriage to Goffin dissolved. Joel O’Brien, Myddle Class drummer, later would contribute greatly on King’s Tapestry. The Goffin and King songwriting team formally ended in 1968, after their divorce, as Carole King began to pursue a solo recording career again.

King and Larkey then relocated to Southern California and the West Coast, Hollywood’s rustic Laurel Canyon area. In 1968 they founded the City, a trio rounded out by New York guitarist Danny “Kootch” Kortchmar. Jim Gordon served as guest drummer on The City’s sessions that yielded one LP, Now That Everything's Been Said that Lou Adler produced.

King chose not to tour at the time, partially due to stage fright; which hampered the album’s commercial success. However, it did include songs later popularized by the Byrds ("Wasn't Born to Follow"), and Blood, Sweat & Tears ("Hi-De-Ho").

Toni Stern and King penned songs for the Monkees’ feature-length movie Head. King, in fact, played guitar on the Monkees’ “As We Go Along.” The percussionist on the date, Denny Bruce, remembers Carole was the piano player on the soundtrack session for the Goffin/King tune “The Porpoise Song (Theme From Head)” that his pal Jack Nitzsche arranged.

The City’s Now That Everything’s Been Said had planted the seeds for King’s 1970 debut Writer and the follow up Tapestry. A rhythm section of Charles Larkey, King and Danny Korthmar really worked well together.

Adler was producing the movie Brewster McCloud and couldn’t produce King’s solo LP Writer, which John Fishbach did and Gerry Goffin mixed. Sadly, the The City did not perform live shows.

“We did rehearse in somebody's office. Maybe a Screen Gems office with Eddie Ho playing drums...nothing ever came of it,” offered Danny Korthmar in a 2011 correspondence. “I played on Carole's demos and we did them all over town. So that's what we doing at Original Sound.”

Those King recordings often utilized drummers Joel O’Brien and Russ Kunkel. “They were very different drummers.Joel was jazz trained and had a lighter touch, but Russ was more solid of a rock musician,” delineates Danny who techniques were influenced by guitarists Cornell Dupree, Eric Gale and Steve Cropper.

Kortchmar was always a fan of Lou Adler’s studio acumen. “I thought Lou was the coolest cat there was...great laid-back attitude in the studio, always got across what he wanted to hear with minimal speech had already made history, had the foxiest chicks,the best taste...I was in awe. After I started doing more and more sessions for different producers it was re-affirmed for me how great he was. I don't remember doubling too many parts, but if I did it was probably Lou's idea,” says Kortchmar. “He was using all kinds of studio stunts I had no clue about at the time.”

Then came Tapestry which struck a universal chord at an opportune time in pop and rock music history - the intersection of folk-rock's introspective and a socially conscious sense of disturbing forensic romanticism in a planet-gone- wild. With the escalating rise of West Coast naturalism centered in the saturated Los Angeles music sector known as Laurel Canyon.

Tapestry blared worldwide and spun on various radio formats, particularly in North America. The new so-called 'progressive' or 'underground free-form' radio stations were eager to spotlight their own artists and playlists separate from the mainstream Top 40. King’s close pal James Taylor - who played on five Tapestry tracks – had previously released "You’ve Got a Friend" as the first single from his new album, Mud Slide Slim and the Blue Horizon.

Carole King had met James Taylor and became close friends since meeting beforehand in New York at a Flying Machine gig. Taylor, Pisces, encouraged her to pursue a solo career. 1970's Writer emerged and then in 1971, Tapestry, a calm, reflective undertaking which proved important in the development of the singer/songwriter genre.

Tapestry scored a pair of hit singles, "So Far Away" and the chart-topping "It's Too Late," whose flip side, "I Feel the Earth Move," garnered major airplay as well. Due to the relentless promotional efforts of A&M Records, as well as Adler’s own hired independent promo man, Carole King was a recording artist who received regular exposure in both the AM and FM radio worlds on “It’s Too Late,” a song about termination and appreciation co-written with poet Toni Stern.

Record producer Lou Adler had existing ties to pivotal Los Angeles area radio deejays, nurtured and developed from his years with AM radio hitmakers Jan & Dean, Johnny Rivers, Barry McGuire, and the Mamas & Papas, in addition to forging bonds with musical messengers Sam Cooke, Lou Rawls, and his mentor Bumps Blackwell.

Adler’s former management client with Herb Alpert, deejay B. Mitchel Reed on KMET-FM, constantly spun and touted Tapestry. The influential R&B deejay, the “Magnificent Montague, a onetime fixture on soul station KGFJ-AM, later in 1972 on his brief XPRS-AM radio shft in his inviting tones also sequenced “It’s Too Late,” “Listen to the sister sing and listen to Lou baby swing!” All during 1971 Tapestry was reported on several key R&B record charts.

About her Grammy winning composition “You’ve Got A Friend,” Carole King revealed the genesis of the song to Lou Adler in a taped interview session on October 18, 1972 A&M studio in Hollywood, CA.

“Once I got to the stage of recording, I have feelings of wondering about whether it’s going to make it or not for a time, but the big questions about, you know, whether it’s going to make it or will people like it, all the big insecurities really happen when I’m writing the song. Once the song is being written and once it’s finished and I play it for you, and a few people whose opinions I respect, I begin to get a feeling. Sometimes I already have the right feelings. Sometimes I don’t know. I didn’t write it with James or anybody really specifically in mind. But when James heard it he really liked it and wanted to record it.

“At that point when I actually saw James hear it, I watched James hear the song, and his reaction to it. It then became special to me because of him, you know, and the relationship to him. And it is very meaningful in that way but at the time that I wrote it. Again, I almost didn’t write it. When I write my own lyrics I’m conscious of trying to polish it off but all the inspiration is really inspiration, really comes from somewhere else. That was because his album Sweet Baby James was recorded the month before Tapestry was recorded I think or even possibly simultaneously. Parts of it were simultaneous. And it was like Sweet Baby James flowed over to Tapestry and it was like one continous album in my head, you know. We were all just sitting around playing together and some of them were his songs and some of them were mine.”

In their same 1972 interview, King disclosed the Tapestry title origins.

“It is typical of the magic that seems to surround that album, a magic for which I feel no personal responsibility, but just sort of happened, that I had started a needlepoint tapestry, I don’t know, a few months before we did the album, and I happened to write a song called ‘Tapestry,’ not even connecting, you know, the two up in my mind. I was just thinking about some other kind of tapestry, the kind that hangs and is all woven, or something and I wrote that song. And, you being the sharp fellow you are, (giggles), put the two together and came up with an excellent title, a whole concept for the album.”

In that encounter King discussed songwriting with Adler.

“The music is always again inspiration but I have more control of the musical inspiration. In other words, if I get a musical idea, if I just get a glimmer of a musical idea, I can make that go much more how I want it to go. If I get a lyrical inspiration I really have to work hard at controlling it. I really can’t control it. And most of the good lyrics that I have written have just sort of come to me without any control. The only control that I excerpt is in editing which I’ve always done to Gerry’s lyrics and Toni’s lyrics. I’m a very good editor and that’s the craft.

“Once I got to the stage of recording I have feelings of wondering about whether it going to make it or not for a time, but the big questions about, you know, whether it’s going to make it or will people like it, all the big insecurities really happen when I’m writing the song. Once the song is being written and once it’s finished and I play it for you, and a few people whose opinions I respect, I begin to get a feeling. Sometimes I already have the right feelings. Sometimes I don’t know.”

Dr. James Cushing, (ret.) of the English and Literature department at Cal Poly San Luis Obispo and a former deejay on KEBF-FM who hosted Miles Ahead, his weekly music show programmed Tapestry selections on his jazz show.

“With Tapestry King and Adler changed the landscape,” proclaimed Professor Cushing. “Each song has its own atmosphere. ‘It’s Too Late’ as a pop tune it had a winning hook, an old school set of musical values. On my jazz shift I’ve played Johnny Hammond Smith’s version of ‘It’s Too Late.’

“Part of what she was bringing into Tapestry was that Brill Building enthusiasm combined with an early ‘70s melancholy. During her Brill Building days, she wrote songs of innocence -- teenage dreams coming true. But after 1968, we knew that not all of our dreams were going to come true. Some of them get shot to death in the kitchens of hotels. Tapestry has a secret political message: it's too late, baby, though we really did try to make (a difference).

“The album was recorded on the corner of Sunset Blvd. and La Brea Ave, not 42nd street! The songs are not about the urban theater of human passion. Carole King had the craft of fitting the words to the tune marvelously. One does not come away from Tapestry feeling that a literary-dramatic sensibility has been succesfully harnessed to music, which is what one tends to feel with Dylan or Joni Mitchell. Part of this Brill Building craftsmanship she developed involved a simplification of poetic imagery. The songs emphasize statements over images, and if the song uses metaphor, it sticks to one metaphor: ‘I feel the earth move.’ And that one metaphor will be developed all the way through. The Motown songwriters did that too,” reminds Cushing.

“Writer and Tapestry also reiterate the regional impact of Laurel Canyon on not only King’s music but her vocal prowess. These are songs written in the fabled 90046 hip zip code. These audio statements were not crafted in cramped cubicle in an office New York or a home in New Jersey. The climate and weather of Southern California informs the songs and surely the vocal performances. Your freedom of movement and physical comfort is limited in East Coast. The parallel of the limitations of the East Coast weather puts on a person and a creative force and the limitations of the Brill Building. I would offer the natural and organic lifting of those limitations that you get in Southern California. OK. Earthquakes, rain storms, fires but these mother nature acts do not happen every year.

“To live in New York and her early compositions and pairings with Gerry Goffin you are aware that you are always obeying and dealing with the things the city deals you out, Laurel Canyon, Appian Way, they give you that sense of protection from the world simultaneously with easy access to it. What happens with her songwriting, singing and lifestyle is that they all open to reveal what had already been there. A kind of winsome yearning that contains adult experience, i.e. New York, but that exudes youthful exuberance, i.e. Los Angeles,” instructs Cushing.

“The bulk of the songs were written in Hollywood, and the vocals were done in Hollywood. Every one of her vocal reflections and nuances are pre-measured and deliberate, almost story boarded like directors Alfred Hitchcock and Stanley Kubrick, still feel it is fresh, authentic, feel that it comes from an adult sensibility. You still feel it has depth. You still feel these things often associated with the New York style. But yet, you also feel and hear the things we associate with the light, space and airyness of Southern California.

“Tapestry also reveals a situation where sax and flute player Curtis Amy through his association with Adler, receives long overdue exposure. Maybe prior to the 1971 retail release maybe Amy was perhaps the worlds’ most often heard but unknown jazz musician, owing to the fact he took the solo on the Doors’ ‘Touch Me.’ King, until Tapestry, held a similar position of the artist in LA completely well known but anonymous at the same time. Wasn’t that something akin to Carole King’s career before Tapestry? Wasn’t she extremely well known and anonymous at the same time?

“The City was a group and their LP was definitely ‘a Carole King vehicle,’ but Carole could lose herself in a band identity and the product could not be viewed as ‘Carole King’s new thing.’

“Upon the initial LP release you purchased Tapestry because you had an idea of who Carole King was because you had seen her name on many of the albums and singles in your record collection. After playing Tapestry you discover producer Lou Adler. His Ode label before King’s Writer and Tapestry, issued Spirit. Isn’t that enough? John Locke of the group lived in Laurel Canyon in the mid-60s before he relocated to Topanga Canyon with the some of that band, Randy California and Ed Cassidy. Ode is a label that issued Spirit’s ‘Nature’s Way’ first and then King’s ‘I Feel The Earth Move.’”

In December of 1969 Merry Clayton was all over FM radio on her vocal duet with Mick Jagger on the Rolling Stones’ ‘Gimme Shelter.’ A year earlier in 1968, her husband Curtis Amy blew the sax solo on the Doors’ “Touch Me.” Both their names were on the credits on the Tapestry album in 1971.

I’m not suggesting Amy’s classic LP Katanga! with Dupree Bolton that Richard Bock produced at Pacific Jazz Studios in 1963 steered Tapestry to hip jazz radio stations like KBCA-FM or underground free-form radio stations like KPPC-FM, but his name attached to the product didn’t hurt at all.

“Curtis Amy had been in LA since 1955. When he headlined at the Renaissance on Sunset Blvd. in 1961, it signaled his arrival as a bandleader,” reminds writer and music journalist Kirk Silsbee. “There was a great deal of jazz happening in Hollywood at that time. In fact, in retrospect, it looks like something of a Golden Age.

“On Sunset, you could stand in front of Ben Shapiro's Renaissance--where a split bill might be the Horace Silver Quintet with Jackie and Roy—and hit the awning of Gene Norman's Crescendo with a rock. Gene always booked jazz groups with a comic—like Dick Gregory and Cannonball Adderley's band. On top of the Crescendo was the more intimate Interlude, where you might see Julie London or Jeri Southern Further east at Crescent, was the Winners—formerly the Losers--where the Don Randi Trio was installed. Down from Sunset, on Crescent, was Sherry's, a mob place that favored piano trios.

“At Sunset and Wilcox was the Summit, home-base for the Terry Gibbs Big Band. Shelly's Manne-Hole--the only seven-nights-a-week jazz operation-- was on Cahuenga, south of Hollywood Blvd. Then, tucked away off of Sunset at Gardner, was The Bit, the coffee house where the Les McCann Trio broke big.

“As a player, Curtis was always very facile, with a lot of vocabulary under his fingertips. He was a communicator on the horn--you never had to try and figure out what he was saying through the saxophone. He had a strong sense of the melodic; that was key to his playing. It was very astute of Lou Adler to bring him onto the Tapestry sessions. I believe he met his wife, Merry Clayton, on the Ray Charles band.”

Before Clayton’s torrid vocal chores with Jagger on the Stones’ “Gimme Shelter,” Merry was a member of the Ray Charles’ Raelettes and had sung backup on records with Elvis Presley. Jack Nitzsche booked her for his production and groundbreaking arrangement on then Buffalo Springfield member Neil Young’s “Expecting To Fly.”

Nitzsche hired Clayton to sing on the soundtrack to the movie Performance. It was Nitzsche who phoned Merry at home one night in 1969 and politely demanded she sing an overdub on the Stones’ “Gimme Shelter” inside the Elektra Studio on La Cienega Blvd. for producer Jummy Miller.

Clayton was one of the stars of director Morgan Neville’s 20 Feet From Stardom the 2013 documentary film which earned an Academy Award Oscar for Best Documentary Feature.

In 2020 Clayton and Adler were in the studio working on a gospel album.

“I remember I was about to take a girlfriend out to dinner because it was her birthday,” Clayton said to me in a 2008 interview. “I told her I had to go by A&M to go say hi to my husband (Curtis Amy) and Lou,” recpllects Merry Clayton from her home in downtown LA.

“I walk into that big main hallway and here comes Carole King. ‘Merry! Come in. You gotta do this song with me. You gotta do this one little part on this song for me.’ I walked in the studio and I will never forget her hanging over the piano writing musical notes. And she played me the track for ‘Way Over Yonder.’

‘“Wow! I want that song.’ But she told me it was for her album. And I did my part. The song was so fabulous and so churchy to me. So what I love and so what I love doing. And I walked in and nailed it. And Lou and Hank Cicalo the engineer were in the vocal studio C. I was walking down the hallway to leave and I heard it and came all the way back. Oh honey. I was standing next to Carole holding her arm and said, ‘Oh Carole, this is just so good.’ I was on a few other songs. ‘You’ve Got A Friend,’ ‘Smackwater Jack,’ and ‘Where You Lead’ that I did background vocals on with Carole and Julia Tillman.

“Carole King had church in her vocals. You know why? Because she was around church, honey. Carole was around soulful beautiful people. When you surround yourself with soulful beautiful people can nothing come out of you but soulfulness and beauty, and she surrounded herself with that.

“See, Lou and Curtis were like brothers, and Curtis was coming from jazz. Which was cool. As far as Curtis was concerned Lou was his brother. It was a bond between those two that I even saw in Curtis’ death, when Lou came to the hospital by his bedside. They talked about stuff that I didn’t even know they were talkin’ about. By his bedside as Curtis was leaving this earth. Lou was there. They had a very special bond they had created over the years.

“You don’t see that very often between two men. Ray Charles was another one like Lou who came to see Curtis in the hospital. Ray called me. ‘Sister Mary? This is the old man, Brother Ray.’ ‘Yes. Hey Papa, how you doin’?’ ‘The question is daughter, how you doin’?’ ‘Well…I’m not doin’ too good…’ ‘So I told him.’ ‘Oh shit. I’ll be there tomorrow. Tell the doctors I want a conference when I get there.’ I called the doctors and they were standing at attention when he arrived with Joe Adams when they walked through that door. Curtis looked up and said, ‘Ray! I must be sick. Brother Ray is here!’ (laughs).

“Honey, Tapestry was an anointed project,” Clayton beamed. “It had God all over it as far as I was concerned because I could feel it. You know, when you feel stuff. You can feel that music and you can get a little tingle from the back of your neck and up my back. It had magic. It was absolutely magic.”

“On Tapestry Lou and I did quite a few things,” explained engineer Hank Cicalo in an 2008 interview with me.

“There was a thing about the middle of Carole’s voice where it’s almost warmth with a little edge. I always wanted to capture that. I thought her piano playing was great, she would sing, and she was such a writer and performer, she knew when to lay out and when to hit it. So that was always great. Then when her vocals came when you mixed them the spaces were always in the right places. Everything was supporting her voice and that piano. That’s where the nucleus of the whole album was,” revealed Cicalo.

“My thing with drums, in a record I did, Russ Kunkel on this, I always wanted to get the cymbals. Years ago it was one microphone over the top, that kind of thing. But because of the brushes and light cymbal work, and if you listen to those records you will hear it. It’s there. The hi-hat was very important top these records or any of these records, that’s how you sub-divide the bar. Musicians don’t listen to that but they feel it. So to me it was always important people could hear what was in the phones.

“The studio had a Howard Holzer special made console. His board you could really punch it. The only thing I had to worry about was tape there was no noise reduiction in those days, so much easier now. Everything was supporting that voice and that piano. That’s where the nucleus of the whole album was. No matter what happened in that room, it had to support it. You got to remember whole period everything was moving from two-track tapes. I met Carole when she wrote songs for the Monkees, whom I engineered 4 or 5 albums with.

“Lou was the kind of guy, as a producer first of all he had an incredible feeling for songs. He could listen to a tune and go ‘that’s that’s not. Let’s go on to the next one.’ And the way he would work it was amazing. We were mixing the album, I had some other projects going, but about the second week of mixing, we re-mixed some things, I wanted to mix some things, Lou wanted to mix some things and one night we came down, pretty much finished it, let’s listen to it from the top in one of the editing rooms in the back at A&M. Third room.

“We listened to the album Tapestry late at night. Play the whole thing down. The second engineer was there. Lights low and I said to myself ‘this sounds great!’ I don’t mean great engineering. I mean the tunes. It started hitting. I turned around to Lou, we walked out, went to the hallway, and I told Lou, ‘Something is goin’ on here.’ ‘Yea…It’s pretty good…’ That was the first time we really struck on it. All these things, but when we sat down and listened to it then we realized it was something better than normal, a great record coming. And that’s when I felt it and I think that’s when he felt it that night.

“The writer becoming the recording artist or star seemed to be a natural path for people performing as side people. And then they made an album suddenly becoming a star or an artist or performer. And see them grow, but we were all growing the producers, the record companies. The progression was natural.”

Multi-instrumentalist and session musician Chris Darrow is heard on the debut LP of Leonard Cohen, John Stewart's, Willard, James Taylor, Sweet Baby James.

Renaissance man Darrow recommended drummer Russ Kunkel to the producer of Sweet Baby James, and steered the Poor’s bass player Randy Meisner (and future founding Eagles’ member) into the same album. Chris found Sunset Sound studio and the engineer who recorded Sweet Baby James. Darrow first saw drummer Russ Kunkel play at the Whisky A Go Go when he was in a power trio, Things To Come, when they opened for Cream in 1967. Kunkel has credited Darrow with getting him his first paid profiessional studio job.

“50 years I attended the wedding of Carole King to Charles Larkey at their Laurel Canyon home. I went to the Troubadour when Tapestry was released,” Darrow happily volunteered in a 2008 interview. “I saw the early show. It was crowded and almost all the people in the room were women, mostly high school and college age. Almost all of them were with their mothers. Carole King's Troubadour shows had an intimacy about them and everyone in the place felt she was singing to them. Most of the audience was women. 85-90 per cent of them were females but there were certainly some men around. But she wasn't drawing men like Joni Mitchell and Linda Ronstadt.

“I knew Carole King because she played on the Sweet Baby James album, which changed the entire visibility. In a way it also symbolizes New York coming to Los Angeles with Kootch and Charlie. Ralph Schukett was in Clear Light. But JT made it happen,” pondered Darrow.

“It went back to the City album. Abagail Hannis had sung in The City and she was one of the leads in the Hollywood production of HAIR. I caught HAIR when Abagail sang the night Jennifer Warren (Warnes), the main lead star, had her night off.

“I played on an album of a Japanese artist named Myumi Itsua that Carole played on. It was recorded at Crystal Studios with John Fishbach producing, who also produced King’s debut album, Writer. He would later on engineer my first album, Artist Proof, on Fantasy records in 1971.

“At the Troubadour she just played by herself and was really good. One of the things that most people don't understand is that she is a consummate songwriter. She knows form. As a person who played piano for songwriting demos, she had to play the essential song and play everything right down the middle. She was not playing solos, she was playing the song.

“Consequently, as a songwriter and a person playing piano on demos, her great ability was to center in on the song. That's why she was so good with James Taylor. She played the song. She played big chords. She played something that was hook-oriented that fit the song. So for her as a piano player it wasn't about chops, it was about style all the way. So, she wasn't somebody who was gonna play big solos. She was going to accompany the song and play the song. Playing the song is different than playing lead or rhythm. That's why she is so good. Underneath it all, she is still one of the consummate songwriters of our time. Carole and Gerry Goffin wrote some great songs together and she also wrote alone, as a solo artist. She's very talented.

“James Taylor was a great guitar player and his whole style totally suited what he was trying to do as a singer and songwriter. And Carole King had the same thing. Her piano, singing style and her songs all went together. They sounded like they all made sense. And that’s another reason why she was so good.

“The other thing about it, and I don't think many people talk about her that way, was that she was a true feminist,” underlined Darrow. “She was different than Joni Mitchell or Judy Collins. She was different than Linda Ronstadt. There really weren't that many great women around at the time getting national exposure. And she wasn't a folkie at all, but ended up entering into that world due to the venues primarily, but it wasn't because she was a folk music chick.

“She was from New York, and already had major hits as a songwriter. Carole had an understanding of the world of music in a whole other way than most of the songwriters. She was very fortunate to come out of the later day Brill Building area experience on a Teddy Randazzo level. She spoke to women. She wasn't a babe, like Linda Ronstadt. I played on tours and recorded with Linda 1969 -1972 and her road manager for a while as well.

“In Carole's photos, cover art, and such, she wasn't selling sex. She wasn't selling that romantic thing. That's why I think women took to her. She was like every woman. She had this way of speaking to the women of the time in a way in a way Joni Mitchell and Linda Ronsdadt didn't. When Carole sang ‘Natural Woman,’ a song she co-wrote, she sings it in a whole different way. And she doesn't mean it like Aretha means it. She means it on a Laurel Canyon and Topanga Canyon level. She came from New York and was wearing Levis and letting her hair go natural.

“The climate wasn't right for her Writer album when it was first released. Sweet Baby James opened the door for Tapestry. All of a sudden it was OK to be a singer/songwriter. That certainly opened the door for me as a solo artist,” Darrow admitted.

Heather Harris is the former entertainment editor of the UCLA Daily Bruin overseeing the trend-setting Icon and Index sections from 1970-1972 published daily in Westwood, California. She’s now a noted music photographer. (heatherharris.net). As a college student Harris assigned the first ever review of King’s Writer LP in 1970.

“At the Troubadour before Tapestry was released I saw James Taylor introduce her when she performed with him on piano with something to the effect as ‘my very talented and not so well known.’ I loved the album cover of Writer. That is what got my attention at the schoolpaper.

“I was later primed for Tapestry. During my tenure at the Bruin I first saw the Writer promo photo with the maxi-dress, sold at the Contempo Casuals boutique. Then the Tapestry album cover, it was a new style of early seventies. It was very different from what came across my newspaper desk at UCLA in Westwood California. Natural light, not an album cover shot in a photography studio. It looked like it was actually taken in her home with sidelight coming in from the right.

“The whole package and especially the cover made a big impression. The power now is diminshed in the CD format. The LP covers then were vital for exposure and made impact. Now if you’re not on YouTube you’re not gonna know what they look like. It was obvious Carole King really was going to be a successful singer/songwriter in that era of the business in a way that Carole Kaye was a successful bass player in the music business. Both are strong female figures. Even if they are not loud spokespeople they succeeded.

“Carole had cross appeal because she sounded like her audience. The initial core people in the throng who believed they could have written it. It’s deceptive like the way actresses like Jennifer Aniston of Friends has a huge female base. They think they can sort of look like her if they gave the effort. In the same way a lot of her audience thought they they sort of sort of thought they could write really nice songs like ‘So Far Away’ if they really gave the effort. Forgetting of course, that people who are really good at something make it look easy. I really give King credit what she was doing at the time what she did. She made chill out music. Everyone else was tossing the words and music in our face at a louder level. Laura Nyro was first.

“On Tapestry here is someone who looked like she was similar to our age but even if she was older. And a lifestyle of a rich hippie, and she does these nice songs. Carole looked like the audience. Laura Nyro didn’t. I liked Laura Nyro a lot. But I was also chilling out to UK folk rock like Fairport Convention and Pentangle,” Harris proudly attests.

SiriusXM deejay and veteran music tastemaker, Rodney Bingenheimer attended King’s famed 1971 Troubadour club debut. Rodney, then a weekly columnist for GO! magazine, totally dug King’s live set but split the scene with some reservations.

“I knew her name and loved the songs she wrote over the years, especially the things for the Monkees. I went to see Laura Nyro at the Troubadour earlier and wrote about it for GO! magazine. I loved it! Not what I saw her do at the Monterey International Pop Festival in ’67.

“Carole King at the Troubadour was a hippie girl on the piano bench, but like a soul singer, and I knew she wrote the songs. But…I thought it was going to be like a big soul and pop music gig. Loud, pop, ‘Lou Adler-type music,’ Jan & Dean, the Mamas & Papas, ‘the ‘United Western recording studio sound’ with tambourines and handclaps. I was shocked. I liked it a lot, not boring, but I was hoping it would be like Spector snf Monkees’ songs, and lots of things Carole King did with Gerry Goffin. Pop stuff,” Bingenheimer laments.

“This was a change in the music coming from Laurel Canyon. The audience was over age 21! I wasn’t used to that coming out of the sixties and the Sunset Strip clubs in Hollywood. I was sorta hoping some of the Shirelles would walk off Santa Monica Blvd. and join her on stage for ‘Will You Still Love Me Tomorrow,’” laughed Rodney.

Musician Jeremy Gilien holds a Master's degree in Music Composition from California State University, Los Angeles. He has served as a church organist, operatic accompanist, and played piano and Hammond organ in many rock groups, including The Paler's Band, which performs the music of Procol Harum at international festivals and concerts. He has taught music at the Los Angeles County High School for the Arts since 1985. Vocalist Josh Groban was a former student of his for three years.

About Tapestry, educator Gilien states, “Carole King on Tapestry utilized harmonies popularized by Holland-Dozier-Holland in the Motown sound, especially major sevenths to sweeten, and minor sevenths to warm the sound. She employed extended dominant harmonies, such as chords of the 9th, 11th, and 13th, in lieu of traditional 7th chords at half cadence points preceding choruses. A feature which is a fairly frequent characteristic of her formal songwriting structure is to begin a song in a minor key and then find her way into a sunnier, major region before returning again to minor.

“This method can be heard in such songs as ‘It's Too Late.’ ‘I Feel the Earth Move,’ ‘You've Got a Friend,’ and ‘Beautiful.’ The absence of an orchestra or large string section, and inclusion of finely crafted instrumental solo breaks lend a sparse intimacy and a solidarity with the band-oriented rock music that Lou Adler produced. The quality of her voice did not compare with that of a first rank R&B or blues singer, but she used her understanding and placement of idiomatic vocal ornamentation to supply the 'soul' that her natural limitations had not equipped her with. Her sound was sensitive, unique, endearing, and certainly a far cry from what we would think of as a typical 'songwriters' voice.”

“Tapestry is a touchstone, not only for her generation, but the songs are touchstones,” describes keyboardist and author Ken Kubernik, a contributor to Variety earlier this century.

“Having left the restrictions of the Brill Building songwriting world, the late ‘60s and very early ‘70s brought some artists who brought a new sensibility, writers who reacted against writing for others and chose to go out and ‘do your own thing.’ At obviously at a certain point Carole made the trastion of being the artist and product herself, She makes the transformation doing her own thing, finds the strength and character to get over her fear of performing and works herself, as her fellow artists are going through the same arc. Neil Diamond left the staff writing songwriting world. Carole and others all start making this move, going from the impersonal, the large product placements to the very intimate and personal. It’s a narcistic act on one level because going from the impersonal to deploying ways that were very subtle.

“But there is a deeper connection,” Ken underlines. “Young girls are looking to her as a sensitive singer/songwriter that spawned the whole generation and guys related to girls who were feeling emotional. It was a wonderful way to reach a girl. King’s songs became a valentine that guys could use to win over the hearts of girls. King is taking control of her feelings. She is empowering herself. So Carole King was putting herself out there in a way that was very dramatic. She is painting and playing her songs that were so radio friendly and were not threatening at all. And, at the same time there was this consummate craftsmanship. She was simply too good at what she did that you couldn’t deny it. She rode on the coat tails of other possibly more deeper and more profound artists. But they didn’t have the commercial breakthrough, but she did. She took a lot of the same themes that were all a constellation around them, but she didn’t have to prove anything because she had been there years before those people.

“The players on Tapestry served the songs. Half the piano and parts are split between King and Ralph Shukett. Where you might assume the hard percussive nature of ‘I Feel the Earth Move’could have been a basher like Shukett, it was King. He’s on electric piano on half the cuts. King and Adler together knew when it was appropriate you bring in the right people to execute your ideas. It’s a consummate artist record. King is savvy enough to know her strengths and weaknesses and not afraid to substitute for specific tracks.

“Tapestry was not overproduced by Lou Adler. King is a songwriter paramountly,” volunteered Ken. “She’s not a great singer by any measure. The one through line obvious in Tapestry is Adler’s awareness of the primacy of the song, above all else. Whatever forces were at work decided for him to go in this direction andKing caught the zeitgeist. She got the wave.

“The right lace at the right time. She was just edgy enough, not so far out. And, the industry was really confortable. A sense of her willingness to come out and sing in post-Dylan world you didn’t have to have a perfect voice. You had to have an individualistic sound. This emerged from Writer that developed as singer and tunesmith from her work in The City’s album, and teaming with Adler as focal point. Rhythm section and principal musicians had already recorded with Carole and Lou.

“Tapestry is indeed a sea change in the record industry for this golden period. Where the anonymity of a previous generation, so called ‘Wrecking Crew’ studio musicians on Adler’s Jan & Dean and Mamas & and Papas records, where no one really knew their names except for a handful of people. To be honest, their names are rarely put on the back of an album, or ghosted, not documented, you really didn’t know who these people were unless you were part of the record industry or music business on some level.

“In 1971 when you are sitting around listening to Tapestry you are not just reading the lyrics and talking about the artist, you are saying, ‘Who played bass? Who played drums?’ It’s because you are seeing their names again and again on all your favorite records. Suddenly, there is a shift where the musicianshsip, the very skill set to create a personality on a record is more than simply Billy May and an orchestra at the Capitol Studios. Names you will never hear and Frank Sinatra singing on top of it. This is also crucial, because all these individuals want to matter. They are not going to be content to be Carole King and nameless session players. Adler also has a deep seated awareness of A&M studio, and a pass port to King’s songbook very few had.”

Harvey Kubernik 2008 interview with record producer Lou Adler on the making of Tapestry.

HK: You also had a friendship with Carole that was 10 years old before Tapestry began.

LA: That came from working as her publisher in a sense from having the West Coast office of Aldon Music. So, that when she moved out her in 1968, and I had known her since 1961. I was one of the people in California of a small group that she knew, so her coming to record with me was sort of natural. If she was going to record it was a person that she knew from the Aldon days. It was that sort of relationsup. I was involved with her kids, somebody that was around her family and really cared about her daughters. I’m not anywhere near as close now to Carole as I was in those days. My feelings and my respect for her, certainly as an artist continue. And I treasure the time that we had together.

Q: Tell me about the atmosphere at A&M Records at the time you produced Tapestry. You did the record on the lot and they distributed your Ode label.

A: A&M itself, you can’t imagine the heads of some labels coming to some sessions and then standing next to you and saying thing, but with Herb (Alpert), because we had been previous business partners and his musicianship, and my respect for him, as co-head of that label, I was totally confortable with that. You could talk to him on a music level. I had my own promotion man within the A&M structure so that helped a lot. The people at A&M loved music. They were not there for any other reason. The fact that a musician who co-owned a label.

As far as the first Tapestry playback and the advance buzz, you didn’t have to do much. We sent out the mailing to radio stations and record reviewers. The first review we got back from The Long Beach Press Telegram was a bad review. Whoever wrote it talked about Carole’s voice being thin. But there was no other plan other than get it out there and let people hear it. The response on the lot itself, visualize it at the time was like a college campus. Everybody talked to each other about all the products during lunchtime, and the word on the A&M lot was fantastic, and the kind of responses that validated what we had done. “This album is so personal and this album I can listen to over and over and it reminds me of things that I’m going through.” That permeated throughout the years it has continued to sell. Each time from vinyl to CD to downloads. Somebody buys Tapestry again because they want to listen to Tapestry in the new mode. It just became personal to everyone who listened to it. There were enough songs in there for people to pick up this song and that song. “So Far away” is my favorite song. At the time of the initial release we were still thinking AM radio as far as singles. FM radio still had an undergound feel to it. The choice of “It’s Too Late” as a single came from (A&M co-owner) Jerry Moss.

The differnce between Tapestry and other albums I had been involved in was the word of mouth. On “It’s Too Late” Curtis Amy is on sax. But the distinctive flavor he added to Tapestry was his flute. He hadn’t played flute in a very long time and he was nervous about it ‘cause he had just been playing sax. I said, “we’re gonna use flute on this.” Curtis said, “Give me a couple of days to work on it.” Curtis and his wife Merry Clayton were both fantastic and were a very important part of Tapestry.

Q: Reflect on Tapestry.

A: I really knew that it was special. It brought out emotions that no other record at least at that time had.Tapestry was really special and hit a real chord with the public.”

Q: The pre-production period was fundamental to Tapestry. Over the decades you have cited the influence of jazz vocalist June Christy’s Something Cool LP with arranger Pete Rugolo.

A: It’s one of the first albums that I started noticing sequence and continuity of songs and thoughts, so that it wasn't a roller coaster emotional ride, it was a smooth ride. Musically, if there's one other thing, Peggy Lee with George Shearing, who connected some instrument to his piano playing. He doubled the vibes, he doubled the guitar, you know?

“You'll hear on Tapestry, if you go back and listen to it, I doubled a lot of Carole's parts with Danny Kortchmar's guitars. So for me as a producer, those were two real influences, but especially the June Christy album. Carole’s piano playing on the demos dictated the arrangements.

“What I was trying to do was to re-create them in the sense of staying simple so that you could visualize the musicians that were playing the instruments. And also tie Carole to the piano, so that you could visualize her sitting there, singing and playing the piano, so that it wasn't 'just the piano player,’ it was Carole. And that came from the demos, which would start with Carole playing and singing, as well as doing some of the string figures, always on piano.

“During pre-production I had in my mind to use a lean, almost demo-type sound. Carole on piano playing a lot of figures with a basic rhythm section, Russ Kunkel and Joel O’Brien on drums, Charles Larkey, bass, Danny “Kootch” Kortchmar, guitar, Ralph Schuckett on the electric piano, along with David Campbell doing the string section. I also had Curtis Amy on sax and flutes, his wife Merry Clayton, and Julia Tillman. James Taylor added acoustic guitar to ‘So Far Away,’ ‘Home Again,’ and ‘Way Over Yonder’ on the album. James is also on ‘Will You Love Me Tomorrow’ and along with Joni Mitchell is one of the backing vocalists on ‘You’ve Got A Friend.’

Q: Run down to me about selecting the songs for Tapestry.

A: In selecting the songs we had 14 songs that we were considering. One of which was “Out In The Cold” that didn’t make the initial album, which we later issued as a bonus track that’s on CD. Carole would play the songs, some that she had written, or was finishing, and some that she wrote during the album. Everything that we selected I obviously felt should be on the album and we didn’t have that many songs that we were leavng out.

“The pre-production consisted of coming up to my office on the A&M Records lot after Carole would play all the songs, and at that point we think about musicians that would fit. We had this little core group of musicians. The difference on the tracks really lies with the drummer. On things like ‘Home Again’ and ‘So Far Away’ was Russ Kunkel, and on the more uptempo ones was Joel O’Brien. We eventually recorded all of those tracks in the A&M Studios, B and C.

Q: Let’s talk about some of the songs on Tapestry. “So Far Away.”

A: “So Far Away” is my favorite song on Tapestry. I use the phrase a lot, “Doesn’t anybody stay in one place anymore?” It’s the road, it’s the people traveling. It just seems to me an anthem of that particular time and so well written and one of the earlier songs she wrote for this album.

Q “Way Over Yonder.”

A: Merry Clayton does a tremendous background vocal on that track. It’s a song that is a little different than most on Tapestry. Dramatic. A Dionne Warwick style. But Carole is able to pull it off.

Q: “Natural Woman.”

A: Once again it’s a Goffin and King song but written with Jerry Wexler. Of all the songs on TapestryCarole had more trepadation about doing it because of the Aretha Franklin record, but I think in the way that we did it was very much like Tapestry. I don’t think you hear it in terms of production. It’s Carole and Charles Larkey, it’s as close to a demo as you can get. Piano, vocal and bass and it’s all about the song. She’s certainly not trying to outdo Aretha Franklin, and I’m not trying to out do Jerry Wexler in terms of production. We’re presenting a great Goffin and King song.

“In 2007 I spoke to Jerry Wexler at his home in Florida, and he told me the story that Gerry was coming out of a building in New York, (Goffin now remembers it as an Oyster House), and Jerry Wexler is passing in a car, and yells out, ‘Why don’t you write a song called ‘Natural Woman?’ They felt the title was so distinct and so important to the song that they gave him a piece of it. So, when I spoke to Jerry recently to call him on his 90th birthday, he said, ‘isn’t it amazing what those kids gave me? The checks keep coming in and I’m really happy about it.’ Knowing how much he added to the song, not really as a third writer but the title and the inspiration of what was to be, a great song.

Q: Tell me about the initial playback of Tapestry.

A: I recall wallking out of the studio after a playback with Danny Kooch, and he said, “what do you think of this?” He misinterpreted I think when I replied “it’s the musical equivilent of Love Story,” which was a number one move at that time. And Kootch, felt, “that’s a little soft.” What I meant was that it was an emotional album that was going to be very big and bring out emotions in people that no other record at least until that time had.

Q: What about the post-production after the recording aspect was completed

A: Carole never expressed this is really good or this is going to be real big. I think she was happy with what we were doing. During the Tapestry sessions she was very confident, very business-like and organized. She takes problems that occur in the sessions as good as anybody I ever worked with, fine, get it fixed. She had a real calmmess about her. if there is a fire you don’t see it on the surface

“As far as the post production, after you do all the recording, mixing, I closed the doors to the mixing room, and I played Carole the mixes after they were done, if she had any suggestions we would then go in and fix the mix. But she never asked to be there during mixing and I don’t feel she felt left out. When I felt the mix was final to a point, then she would listen and might have suggestions or comments like, ‘That’s it,” “That’s fine” or “I think the vocal has to be up or you missed that part.”

Q: The sequencing on Tapestry was crucial. Extra space separated the tracks.

A: When I started sequencing Tapestry, I remembered and thought the sequenceing on June Christy’s Something Cool was incredible, the transition from song to song just kept you in the album. It was something that I tried to accomplish with Tapestry. I took the tapes home and I went through a lot of changes.

“I finally fixed on the sequence and took a vacation to my house in Mexico that had a small cassette player and that’s when I came up with the final sequencing. But I went through a lot of changes. John Phillips of the Mamas & Papas influenced me a lot on sequencing and what the final chord on one song is to the first note on the next one so it’s not jarring music transitions.

“Sequencing meant a lot in those days, the journey, or the experience or the adventure of listening to a new album and sitting down by yourself puttng on that vinyl, the story that it told, the sequencing was very important. I was sequencing for the person who was listening at home, alone.

Q: How does Tapestry fit into Carole’s body of work?

A: Well I think it is the epitomy the matching of the songwriting with her piano playing and her vocalizing. The producion allows all of those things to be forefront. It’s not a ‘Spector’ sound as her own sound. We got a little away from the subsequent albums we did after that.

“The group of Tapestry songs have that many right songs on an album, songs that compliment each other. Songs that trasmit everything that is right about Tapestry. What would I do different? Everything was done right for whatever the reasons were. Once again it’s Carole King as a songwriter.

Harvey Kubernik is the author of 19 books, including Canyon Of Dreams: The Magic And The Music Of Laurel Canyon and Turn Up The Radio! Rock, Pop and Roll In Los Angeles 1956-1972. Sterling/Barnes and Noble in 2018 published Harvey and Kenneth Kubernik’s The Story Of The Band: From Big Pink To The Last Waltz. For late summer 2021 the duo has written a multi-narrative volume on Jimi Hendrix for Sterling/Barnes and Noble.

Otherworld Cottage Industries in 2020 published Harvey’s book, Docs That Rock, Music That Matters, featuring interviews with D.A. Pennebaker, Chris Hegedus, Albert Maysles, Murray Lerner, Morgan Neville, Dr. James Cushing, Curtis Hanson, Michael Lindsay-Hogg, Andrew Loog Oldham, Dick Clark, Ray Manzarek, John Densmore, Robby Krieger, Travis Pike, Allan Arkush, and David Leaf, among others.

This century Kubernik wrote the liner note booklets to the CD re-releases of Carole King’s Tapestry, Allen Ginsberg’s Kaddish, Elvis Presley The ’68 Comeback Special and The Ramones’ End of the Century). Harvey and Andrew Loog Oldham wrote the liner essays to The Essential Carole King.

In November 2006, Harvey Kubernik was a speaker discussing audiotape preservation and archiving at special hearings called by The Library of Congress and held in Hollywood, California.

Kubernik’s writings are in several book anthologies, most notably The Rolling Stone Book Of The Beats and Drinking With Bukowski. Harvey penned a back cover endorsement for author Michael Posner’s book on Leonard Cohen that Simon & Schuster, Canada published in October 2020, Leonard Cohen, Untold Stories: The Early Years).

Kubernik’s 1995 interview, Berry Gordy: A Conversation With Mr. Motown appears in The Pop, Rock & Soul Reader edited by David Brackett published in 2019 by Oxford University Press. Brackett is a Professor of Musicology in the Schulich School of Music at McGill University in Canada. The lineup includes LeRoi Jones, Johnny Otis, Ellen Willis, Nat Hentoff, Jerry Wexler, Jim Delehant, Ralph J. Gleason, Greil Marcus, and Cameron Crowe.

In 2014 filmmaker Matthew O’Casey included Harvey in his BBC-TV documentary on singer Meat Loaf, titled Meat Loaf; In and Out of Hell, broadcast in 2016 on the Showtime Cable TV channel.

During 2020 Harvey Kubernik served as a Consultant on the 2-part documentary Laurel Canyon: A Place in Time directed by Alison Ellwood. Kubernik is currently working on a documentary about Rock and Roll Hall of Fame member singer/songwriter Del Shannon.

Harvey is also spotlighted for the 2013 BBC-TV documentary Bobby Womack Across 110th Street, directed by James Meycock. Womack, Bill Withers, Ronnie Wood of the Rolling Stones, Damon Albarn of Blur, the Gorillaz and Antonio Vargas are featured.

In 2020 Harvey Kubernik was an interview subject in the Chris Sibley & David Tourje-directed short documentary entitled John Van Hamersveld: Crazy World Ain’t It. Van Hamersveld designed the iconic Endless Summer visual image and album covers for the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, Jefferson Airplane, Grateful Dead, the Beach Boys, the Kaleidoscope, and Blondie.

During 2019 Harvey was filmed for director Matt O’Casey on his BBC4-TV digital arts channel Christine McVie, Fleetwood Mac’s Songbird. The cast includes Christine McVie, Stan Webb of Chicken Shack, Mick Fleetwood, Stevie Nicks, John McVie, Heart’s Nancy Wilson, Mike Campbell, Neil Finn, and producer Richard Dashut. The premiere broadcast was in September 2020.

Kubernik was interviewed by director/producer Neil Norman foir his GNP Crescendo documentary, The Seeds: Pushin’ Too Hard. Jan Savage and Daryl Hooper original members of the Seeds participated along with Bruce Johnston of the Beach Boys, Iggy Pop, Kim Fowley, Jim Salzer, the Bangles, photographer Ed Caraeff, Mark Weitz of the Strawberry Alarm Clock and Johnny Echols of Love. Miss Pamela Des Barres supplied the narration. Debut broadcast on television will be in 2021.

This decade Harvey was filmed for the currently in-production documentary about former Hollywood landmark Gold Star Recording Studio and co-owner/engineer Stan Ross produced and directed by Brad Ross and Jonathan Rosenberg. Brian Wilson, Herb Alpert, Richie Furay, Darlene Love, Mike Curb, Chris Montez, Bill Medley, Don Randi, Hal Blaine, Shel Talmy, Don Peake, Kim Fowley, Johnny Echols, Gloria Jones, Carol Kaye, Marky Ramone, David Kessel and Steven Van Zandt have been lensed.