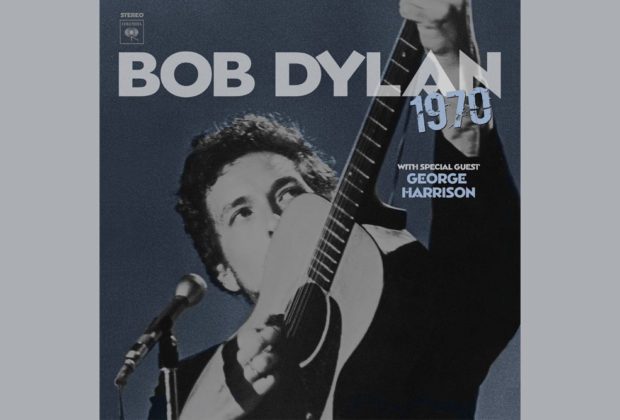

Columbia Records and Legacy Recordings, the catalog division of Sony Music Entertainment have just released Bob Dylan - 1970, the first widely available pressing of a three-disc collection of long-sought-after studio recordings.

The recordings on Bob Dylan - 1970 were first released in a limited edition on December 4 as part of the Bob Dylan - 50th Anniversary Collection copyright extension series (which began in 2012). The attention surrounding the 1970 performances, notably Dylan's studio sit-down with George Harrison on May 1, created a demand for a broader release of these historic tracks.

Bob Dylan - 1970 includes previously unreleased outtakes from the sessions that produced Self Portrait and New Morning as well as the complete May 1, 1970 studio recordings with George Harrison, which capture the pair performing together on nine tracks, including Dylan originals ("One Too Many Mornings," "Gates of Eden," "Mama, You Been On My Mind"), covers (the Everly Brothers' "All I Have to Do Is Dream," Carl Perkins' "Matchbox") and more.

The recording sessions for this collection occurred during March 3-5 and May 1, 1970 at Studio B, Columbia Recording Studios, New York City, New York and June 1-5 and August 12, 1970 at Studio E, Columbia Recording Studios, New York City, New York.

The compilation was produced for release by Jeff Rosen and Steve Berkowitz culled from recording sessions originally produced by Bob Johnston.

Bob Dylan - 1970 comes housed in an 8-panel digipack featuring new cover art and liner notes by musician and writer Michael Simmons.

“I’ve always loved the Self Portrait/New Morning/Another Self Portrait era,” Simmons emailed me in January 2021.

“Dylan’s experimenting — in addition to New Morning’s then-new and still-powerful songs, he was having fun in the studio, immersed in music by others that he loved. He noted in the recent Rolling Thunder doc that ‘Life is about creating yourself.’ In these outtakes we hear him doing just that.”

“Bob Dylan’s role in American culture today is such that, at some deep level in the national collective mind, he is simply not allowed to release anything unsatisfying under his name,” poses poet and deejay, Prof. James Cushing, who recently retired from the Cal Poly San Luis Obispo Literature and English Department.

“On the infrequent occasions when he does, that unsatisfying work will be revised, reclaimed, re-edited, re-mixed, repurposed, and re-conceived until it is rescued, and becomes satisfying.

“Martin Scorsese has led the way in Dylan reclamation projects on the screen, re-editing Eat the Document into No Direction Home and assembling Rolling Thunder: A Bob Dylan Story in such a way that excises any mention of Renaldo & Clara.

“Bob Dylan 1970, best understood as an extension of 2013’s Another Self Portrait (Bootleg Series Vol. 10), represents a further step in a historical reclamation project: how can we make sense out of, maybe even ‘rescue,’ the Self Portrait album as it was released to shock and confusion in May 1970?

“Both these albums work to reclaim Self Portrait in at least two ways. First, they seem to assume that the album as released showed Dylan masked, concealing himself behind Nashville studio production. Here are the songs without that mask. Stripped of their glossy overlay, songs like ‘Belle Isle’ and ‘Days of ’49’ emerged as tough, honest folk performances. Bob Dylan 1970 has no gloss at all — it’s loose, playful, sloppy in places, and as intimate and spontaneous as the original Basement Tapes, one of Dylan’s blue-chip albums.

“Second,” continues Cushing, “these albums ask that we hear the beloved New Morning essentially as sides Five and Six of the unloved Self Portrait. We know from Chronicles that the two albums were always companion pieces, and now the later LP gives some of its vitality to the earlier. A lot of Bob Dylan 1970 offers rehearsals and approaches to the original songs on New Morning, which benefit from their place in a larger context of American folk music, and the covers, especially ‘Spanish Is the Loving Tongue’ and ‘Thirsty Boots,’ reveal themes that anticipate the originals.

“Bob Dylan 1970 has gotten the bad mouth from some reviewers. Its homespun lack of ambitiousness — ‘for die-hard fans only,’ the internet muttering goes — and its existence being due to the European 50-year copyright law are strikes against it.

“Further, it offers no major new discoveries (for that, Rough & Rowdy Ways will do just fine). But as it enlarges the Self Portrait gallery, it shows Dylan the artist in the act of becoming, searching for the moment when ‘If Not For You’ falls into place.

“If you have a 5CD changer,” Cushing suggests, “I recommend loading it up with Another Self Portrait and 1970, setting it to shuffle, and spending several hours in Bob’s home studio, listening to him trying out brushes and paints, looking for a masterpiece.”

Bob Dylan - 1970 (50th Anniversary Collection)

Disc 1

March 3, 1970

- I Can’t Help but Wonder Where I’m Bound

- Universal Soldier – Take 1

- Spanish Is the Loving Tongue – Take 1

- Went to See the Gypsy – Take 2

- Went to See the Gypsy – Take 3

- Woogie Boogie

March 4, 1970

- Went to See the Gypsy – Take 4

- Thirsty Boots – Take 1

March 5, 1970

- Little Moses – Take 1

- Alberta – Take 2

- Come All You Fair and Tender Ladies – Take 1

- Things About Comin’ My Way – Takes 2 & 3

- Went to See the Gypsy – Take 6

- Untitled 1970 Instrumental #1

- Come a Little Bit Closer – Take 2

- Alberta – Take 5

Bob Dylan – vocals, guitar, piano

David Bromberg – guitar, dobro, bass

Al Kooper – organ, piano

Emanuel Green – violin

Stu Woods – bass

Alvin Rogers – drums

Hilda Harris, Albertine Robinson, Maeretha Stewart – background vocals

May 1, 1970

- Sign on the Window – Take 2

- Sign on the Window – Takes 3-5

- If Not for You – Take 1

- Time Passes Slowly – Rehearsal

- If Not for You – Take 2

- If Not for You – Take 3

- Song to Woody – Take 1

- Mama, You Been on My Mind – Take 1

- Yesterday – Take 1

Disc 2

- Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues – Take 1

- Medley: I Met Him on a Sunday (Ronde-Ronde)/Da Doo Ron Ron – Take 1

- One Too Many Mornings – Take 1

- Ghost Riders in the Sky – Take 1

- Cupid – Take 1

- All I Have to Do Is Dream – Take 1

- Gates of Eden – Take 1

- I Threw It All Away – Take 1

- I Don’t Believe You (She Acts Like We Never Have Met) – Take 1

- Matchbox – Take 1

- Your True Love – Take 1

- Telephone Wire – Take 1

- Fishing Blues – Take 1

- Honey, Just Allow Me One More Chance – Take 1

- Rainy Day Women #12 & 35 – Take 1

- It Ain’t Me Babe

- If Not for You

- Sign on the Window – Take 1

- Sign on the Window – Take 2

- Sign on the Window – Take 3

Bob Dylan – vocals, guitar, piano, harmonica

George Harrison – guitar, vocals (Disc 1, Tracks 20 & 24 and Disc 2, Tracks 2-3, 6-7, 10-11, & 16)

Bob Johnston – piano (Disc 1, Tracks 24-25 and Disc 2, Tracks 1-3)

Charlie Daniels – bass

Russ Kunkel – drums

June 1, 1970

- Alligator Man

- Alligator Man [rock version]

- Alligator Man [country version]

- Sarah Jane 1

- Sign on the Window

- Sarah Jane 2

Disc 3

June 2, 1970

- If Not for You – Take 1

- If Not for You – Take 2

June 3, 1970

- Jamaica Farewell

- Can’t Help Falling in Love

- Long Black Veil

- One More Weekend

June 4, 1970

- Bring Me Little Water, Sylvie – Take 1

- Three Angels

- Tomorrow Is a Long Time – Take 1

- Tomorrow Is a Long Time – Take 2

- New Morning

- Untitled 1970 Instrumental #2

June 5, 1970

- Went to See the Gypsy

- Sign on the Window – stereo mix

- Winterlude

- I Forgot to Remember to Forget 1

- I Forgot to Remember to Forget 2

- Lily of the West – Take 2

- Father of Night – rehearsal

- Lily of the West

Bob Dylan – vocals, guitar, piano, harmonica

David Bromberg – guitar, dobro, mandolin

Ron Cornelius – guitar

Charlie Daniels – bass, guitar

Russ Kunkel – drums

Background vocalists unknown

Al Kooper – organ

August 12, 1970

- If Not for You – Take 1

- If Not for You – Take 2

- Day of the Locusts – Take 2

Bob Dylan – vocals, guitar, harmonica

Buzzy Feiten – guitar

Other musicians unknown

“No one talks about Bob’s piano playing because they don’t know,” multi-instrumentalist Al Kooper stressed to me in a 2010 interview. Kooper recorded with Dylan on Bob Dylan 1970 and who worked with Dylan on previous sessions and stage shows.

“Bob had a very unusual way of playing in that he didn’t use his pinkies. So both his pinkies were up in the air when he played the piano and that’s very interesting to me. It was very interesting looking to watch that. I used to really get a kick out of that.”

Bob Johnston is the producer of the original recording sessions that are housed on Bob Dylan 1970.

Johnston was born in 1932 in Hillsboro, Texas. His career began as a songwriter. He eventually held a staff writing position at Elvis Presley’s Hill & Range Music and often reviewed potential Presley demos and songs earmarked for Presley movies in 1964 and 1965. In addition, Johnston had peripatetic stints talent scouting for Kapp Records and arranging for the incredible Dot Records label. Arthur Alexander did one of Johnston’s songs and so did Mac Curtis, before Johnston joined Columbia Records in 1965. That year he produced Patti Page’s charming yet scary top 10 hit single “Hush, Hush Sweet Charlotte.”

Johnston was initially introduced to Dylan in 1965 when he was called in to replace pivotal record producer Tom Wilson to complete Dylan’s Highway 61 Revisited album in New York City. “I was working with Dylan in New York and I flew in Charlie McCoy from Nashville, introduced him to Dylan,” Johnston told me in a 2007 interview, “and the first thing we cut was a version of ‘Desolation Row,’ with Dylan on acoustic, Charlie on electric and Harvey Brooks on bass.

“I was standing by the sound board and I said to Dylan ‘Listen man, you ought to come to Nashville sometime. I got a fix up down there with no clocks and the musicians are fuckin’ great.’ ‘Hmmm.’ He’d never answer you, just go ‘hmmm’ like Jack Benny… So I finished Highway 61 Revisited and then Dylan called me about six months later and he said, ‘Man, I got a bunch of songs. What do you think about going to Nashville?’ ‘That’s what I was talkin’ about!’

“In 1966 we went down there for Blonde On Blonde. Dylan and I were notorious for using first takes,” Johnston revealed. “He liked to get it out of his head. I don’t see any sense in doing it over and over. They knew what I wanted them to play not what I gave them. That’s why they were there. When I started with Dylan he said, ‘my voice is too loud.’ Good enough. So I turned it down. Then I’d turn it up. ‘Man, I can’t hear myself’ and had that voice out there. Finally, we got to the place where he said ‘I can’t hear myself.’ cause I’d brought it so low. So I told him I’d take care of it and never asked him about it anymore and turned everything up and had that voice out there.”

Johnston, as he did previously in the Nashville sessions for Blonde On Blonde, John Wesley Harding and Nashville Skyline took steps to remove the studio bafflers, a floor space dividing device used to prohibit microphone leakage and the instruments of the musicians from bleeding into each other’s separate sound booths during the sessions.

“I’ll tell you something else I did recording Dylan,” Bob Johnston explained. “What I did was put a bunch of microphones all over the room and up on the ceiling. I would use echo when everything got through and I could do that as much as I wanted. I wanted it to sound better than anything else sounded ever, and I wanted it to be where everybody could hear it. And I don’t know what Dylan would have been if he stayed in New York with those people, and been mixed like that. And I know he would have never done that shit like he did in Nashville,” Johnston insisted.

“Everybody else (at the time) was using one microphone, which means you have to sacrifice something. If you’re gonna have a band, you can’t have the band playin’ full tilt. If you’ve got him in the middle you can’t understand everything with different people (engineers) in there raising the guitar up, raising the drums up, and shit like that. What I always did was that I had three microphones because he was always jerking his head around, and I put the microphone on the left, center and right and it didn’t matter where in the fuckin’ room he went. And then I’d mix and start on the left and go all the way over on the right,” he stressed. “I always had 4 or 8 speakers all over the room and I had ‘em going. The louder I played it the better it sounded to me. This is the way I really did it.

“So I’d usually have the piano on the outside left, without any echo. And then I’d put the echo on the right side. And then I’d have one of the guitars on the right and put the echo on the left…and then I’d match it all alone and brought up everything even so they could fight it out. And then that’s the way the band was. They didn’t have to raise this and lower this, and 15 people sitting around doin’ all that shit. The band was there and he was full-tilt. Then you could go any place in the room and understand him…and I never heard another word from him about anything.

“I would place glass around Dylan for recording,” volunteered Johnston. “He had a different vocal sound. I didn’t make his different vocal sound. He always had different sounds on. I never wanted to be (Phil) Spector… and while the rest of the world was doing an album as big as Blonde On Blonde, which everybody was - the more musicians they could get, the better it was. (But) we went in with four people…in the middle of a psychedelic world!

“As a songwriter, I wrote songs, too, (but) Dylan changed the world. Every song he did I loved. I was a Dylan freak and I knew he was changing the world. I knew he was changing the society as we knew it. And I knew Paul (Simon) was too.”

Charlie Daniels is the multi-instrumentalist who played on Nashville Skyline and other Johnston-produced endeavors, including Bob Dylan 1970.

“When Bob Johnston moved to Nashville in 1966,” Daniels recalled to me in a 2014 interview, “he called me and said, ‘Why don‘t you come to Nashville?’ And I always wanted to live there and packed up in 1967. He had just done Bob Dylan’s Blonde on Blonde. All the good things that happened to me in the early days were because he was a cog in the wheel. One thing that needs to be said about Bob Johnston and bringing people to town like Dylan and Leonard Cohen,” reinforced Daniels. “There was skepticism about Bob coming to Nashville because he was taking the place of a legendary producer, Don Law. Who was an institution in town.

“Here’s this guy Johnston from New York, who had been doing Simon & Garfunkel, Bookends, Dylan, and now Leonard Cohen, who were not really thought of as being country. But the first thing Bob did when he came to town was to do a number one song with Marty Robbins. And in ‘68 produced the albums John Wesley Harding, Flatt & Scrugg’s The Story of Bonnie and Clyde, and of course, Johnny Cash’s live album at Folsom Prison.

“He had gained credibility. He was also at the same time, bringing Al Kooper, Dylan and Leonard Cohen into town who had never lived here. Dylan recorded in Nashville in 1966 for a while, but it was he’d come to town, do his stuff, and leave. Dylan happened to record in a studio in Nashville and worked in it.

“Nobody wanted to work in the big studio until Bob Johnston came to town and basically took it over,” he remembered. “Nobody else wanted to be there. He worked with it, got engineers he enjoyed working with like Neil Wilburn, and he actually brought an engineer from New York with him when he first came down.

“The Columbia Studio was union. In Nashville, in the studios, you had to have the machines to be a certain distance away from the boards so the engineer could not work them both. But the thing I remember mostly about Studio A., the big studio, it was the new studio. The old studio, the Kwansit Hut, was the legendary studio where the hits had been cut. Everybody wanted to work in that room.

“With people like Cohen and Dylan…Most of the Nashville sessions, the country artists they would bring a demo in, they’d play the demo, you play it like the demo, you may change a key on it, but basically it’s gonna be the same thing, how they want the demo. So you’re playin’ pretty much inbounds.

“With Leonard and with Bob Dylan, and it was on a Dylan, and Charlie McCoy was the band leader. And how much do you want him to play? How many bars? How much do you want him to do? And Dylan replied, ‘all he can.’ Well that really describes what this is all about.

“Cohen and Dylan were singers and songwriters. They write their songs, they weren’t coming in from a music publishing company. It was a lot different because there is no hurry. We went into the studio. And of course, Dylan is a big first take guy, if you can get it on the first take that’s how he wants it. And I like that about him. I’m the same way.”

Harvey Kubernik is the author of 19 books, including Leonard Cohen: Everybody Knows” published in 2014 and now available in six foreign language editions. Kubernik also authored Canyon Of Dreams: The Magic And The Music Of Laurel Canyon and Turn Up The Radio! Rock, Pop and Roll In Los Angeles 1956-1972.

Sterling/Barnes and Noble in 2018 published Harvey and Kenneth Kubernik’s The Story Of The Band: From Big Pink To The Last Waltz. For October 2021 the duo has written a multi-narrative volume on Jimi Hendrix for Sterling/Barnes and Noble.

Otherworld Cottage Industries in 2020 published Harvey’s book, Docs That Rock, Music That Matters, featuring interviews with D.A. Pennebaker, Chris Hegedus, Albert Maysles, Murray Lerner, Morgan Neville, Dr. James Cushing, Curtis Hanson, Michael Lindsay-Hogg, Andrew Loog Oldham, Dick Clark, Ray Manzarek, John Densmore, Robby Krieger, Travis Pike, Allan Arkush, and David Leaf, among others.

Kubernik’s writings are in several book anthologies, most notably The Rolling Stone Book Of The Beats and Drinking With Bukowski. Harvey penned a back cover endorsement for author Michael Posner’s book on Leonard Cohen that Simon & Schuster, Canada published in October 2020, Leonard Cohen, Untold Stories: The Early Years.

This century Kubernik wrote the liner note booklets to CD re-releases of Carole King’s Tapestry, Allen Ginsberg’s Kaddish, Elvis Presley The ’68 Comeback Special and The Ramones’ End of the Century.

In November 2006, Harvey Kubernik was a speaker discussing audiotape preservation and archiving at special hearings called by The Library of Congress and held in Hollywood, California.

In summer of 2019, Harvey was interviewed for director Matt O’Casey on his BBC4-TV digital arts channel Christine McVie, Fleetwood Mac’s Songbird. The cast includes Christine McVie, Stan Webb of Chicken Shack, Mick Fleetwood, Stevie Nicks, John McVie, Heart’s Nancy Wilson, Mike Campbell, Neil Finn, and producer Richard Dashut. The premiere broadcast was in September 2020.

During 2020 Harvey Kubernik served as a Consultant on the 2-part documentary Laurel Canyon: A Place in Time directed by Alison Ellwood. Kubernik is currently working on a documentary about Rock and Roll Hall of Fame member singer/songwriter Del Shannon.

Kubernik also appears as a screen interview subject for director/producer Neil Norman’s GNP Crescendo documentary, The Seeds: Pushin’ Too Hard. Jan Savage and Daryl Hooper original members of the Seeds participated along with Bruce Johnston of the Beach Boys, Iggy Pop, Kim Fowley, Jim Salzer, the Bangles, photographer Ed Caraeff, Mark Weitz of the Strawberry Alarm Clock and Johnny Echols of Love. Miss Pamela Des Barres supplied the narration. Norman’s well-received documentary is scheduled for a debut broadcast on television and in various retail platforms during 2021.

This decade Harvey was filmed for the currently in-production documentary about former Hollywood landmark Gold Star Recording Studio and co-owner/engineer Stan Ross produced and directed by Brad Ross and Jonathan Rosenberg. Brian Wilson, Herb Alpert, Richie Furay, Darlene Love, Mike Curb, Chris Montez, Bill Medley, Don Randi, Hal Blaine, Shel Talmy, Don Peake, Kim Fowley, Johnny Echols, Gloria Jones, Carol Kaye, Marky Ramone, David Kessel and Steven Van Zandt have been lensed.