In 1998, for the now defunct Musician magazine, I interviewed Elvis Costello, who was joined by Burt Bacharach, at Ocean Way Recording Studios in Hollywood, California, as they were mixing the Painted From Memory album collaboration. The duo then earned a 1999 Grammy Award for Best Pop Collaboration with Vocals, for their song, “I Still Have That Other Girl.” Burt Bacharach’s debut effort co-writing with Costello on a recording of their song, “God Give Me Strength”, which was specially composed for the film, “Grace Of My Heart”, was nominated for a Grammy Award in March 1997

United Western Studios in Hollywood has been the location for a number of classic hit records, including Ray Charles’ “I Can’t Stop Loving You”, The Beach Boys’ “Good Vibrations”, Frank Sinatra’s “It Was A Very Good Year”, The Mamas And The Papas’ “California Dreamin’” and earlier recordings by Count Basie, Duke Ellington and Stan Kenton bands. Ocean Way in the last couple of decades has also been the site of studio dates for Tori Amos, Bob Dylan, Willie Nelson, Tom Petty, Miles Davis, The Red Hot Chili Peppers, Rod Stewart, Johnny Cash, Barbra Streisand and The Rolling Stones. I went to a bunch of Stones’ sessions a few months earlier when they were doing their recent “Bridges To Babylon” album.

It’s a late summer day on Sunset Blvd., and inside Studio B, Elvis Costello and Burt Bacharach are finishing their long-awaited album collaboration, “Painted From Memory,” for the Mercury label. Ocean Way features the largest exotic tube microphone collection in the United States, and “Painted From Memory” engineer/mixer, Kevin Killen adjusts some faders during a playback, while the Bacharach and Costello “team” huddle and review sequencing.

The album’s musicians include keyboardist Steve Nieve, bassist Greg Cohen, guitarists Dean Parks and George Doering and drummer Jim Keltner. Earlier, during a tracking period while “Painted From Memory” was being cut, Keltner over dinner reflected and discussed the recording collaboration. “I think it’s a perfect musical marriage. I’ve done a lot of work with Elvis over the years and did some sessions with Burt for Roberta Flack, Peabo Bryson and Neil Diamond a while ago.

“First of all,” he continues,” when you’re in the room with Burt Bacharach, you’re aware of that history and all those great songs. So, you’re really on your toes. He and Elvis are both very demanding, so it’s a good feeling when you see them happy with a take. What happens in the best cases is that the songs are so complete that they play themselves. That happened all the time on these sessions. I love for a song to grab me and take me someplace.

“Steve Nieve was on the sessions and I’ve always been a big fan of his since the early Attractions days. He was like a young English Jerry Lee Lewis. I loved watching him study Burt,” Keltner adds, “they were both in my line of sight. After a take sometimes Steve would go over and sit at the piano having just watched Burt play these double-fisted chords with this big sound. He’d be trying to figure out how he did it. Even though Burt is not a technically great piano player, he can inspire a great vocal and a good performance from the rhythm section.”

What about Declan MacManus, p/k/a Elvis Costello? “I’ve always loved Elvis’ singing. His intensity is powerful coming through the headphones. I’m sure there will be a lot of keeper vocals. When he sings live with the band, he doesn’t hold back a bit. His phrasing was great! Which is remarkable, considering all the words he had to deal with. I hope they continue to collaborate. I think they bring out the best in each other,” he concludes.

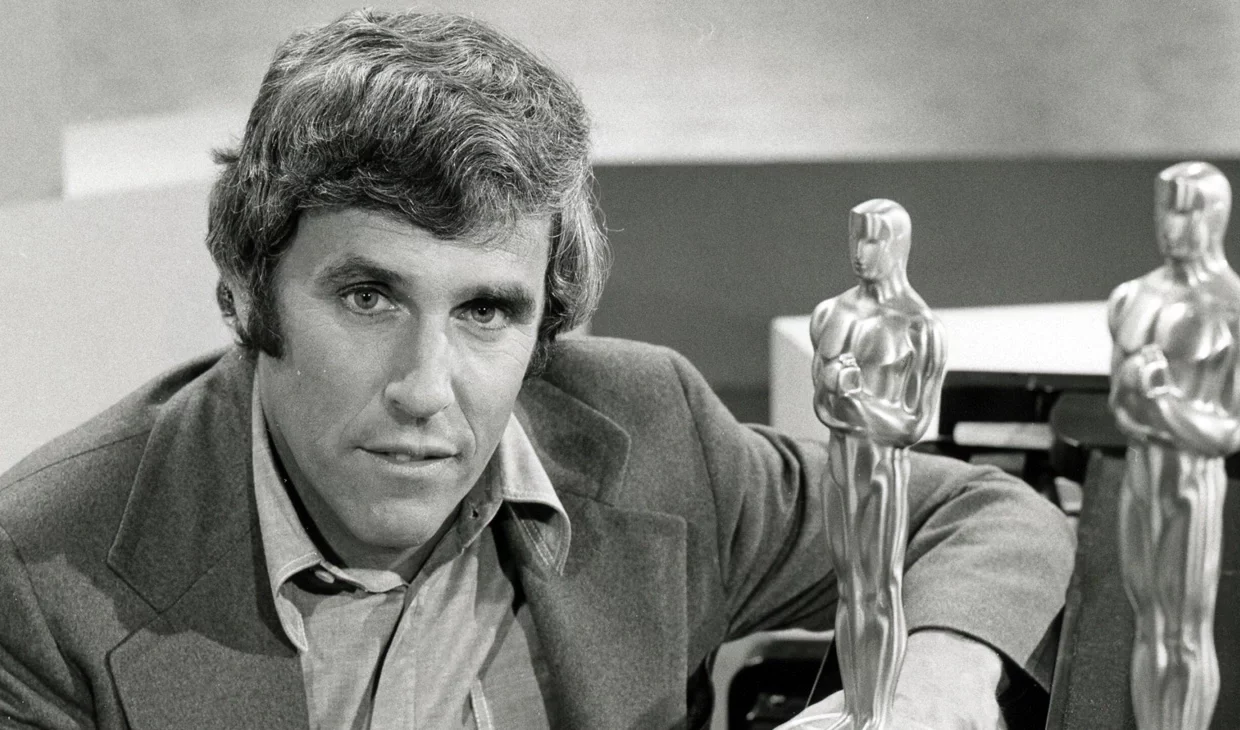

Elvis Costello Burt Bacharach 1998 Interview with Harvey Kubernik

Q: I know the foundation of this Burt Bacharach collaboration goes way deeper than your previous covers of “Baby, It’s You” and “I Don’t Know What To Do With Myself,” as well as including a rendition of a Bacharach selection, “Please Stay,” on the “Kojak Variety” collection. Over the last 20 years, I’ve heard you talk about being exposed to “beat music” on the B.B.C. Light radio programme weekly, and during your dad’s career singing with The Joe Loss Orchestra, he used to bring home all sorts of acetates and advance copies of songs that were to be learned for that week’s radio broadcast. Watching some of these sessions with Burt, I got the feeling this album actually started 35 years ago.

EC: I have a perspective on it that someone of my years probably shouldn't have. I always heard Burt’s tunes in cover form first. And that was important. The stuff that my dad brought home were “A” label singles. Like the Beatles ones I had were the non-single tracks like “Michelle”, and songs from “Rubber Soul” that they (Northern Songs) thought were better suited for covers than, maybe, “Drive My Car” was. They were sent over on demonstration acetates. Rather than having the Parlophone label, which never pressed “Michelle” as a single, Dick James Music (Northern Songs), the publisher, pressed an acetate. And that was how small they were thinking about that “radio cover”.

Q: I feel you had some sort of head start on other record collectors as a pre-teen, since you had more singles than pocket money or any allowance would have bought. Also, this is coupled with the fact you were going to B.B.C. radio broadcasts with your father at ages 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 and 12, and actually meeting in the early sixties bands like The Beatles, The Rolling Stones and The Hollies. These events “informed” this project with Burt.

EC: Oh definitely. It’s all part of it, isn’t it? It’s very natural for me because I grew up also with my mother being a record sales person and really knowing the catalog backwards in a day when being a record sales person was closer to being a librarian than it is now. And that’s how I know all the so-called “standards” that I obviously didn’t grow up with, because they were just around me. I grew up with a band sound around the house, in the sense of my dad being a band singer. And I went to rehearsals as you know, and B.B.C. radio broadcasts with him. I knew my dad was doing something seriously, because he went to work in the evening and he wasn’t a burglar. When I was really young, I couldn’t go to the dance hall. I used to go on the weekend on the afternoon sessions and sit up in the balcony and watch the ballroom dancers, and he would get to play percussion, because the ballroom dancers didn’t like singers because they messed with the rhythm. You and Burt earlier wanted to know why I sing back like I do? It’s my revenge on ballroom dancers, ya know (laughs). And my poor old dad had to stand up there with the three singers on the side, sitting on chairs, getting up to take their vocal turn. My dad would play congas and maracas on the Latin American medley (grins). When my dad did the Royal Command Performance, in 1964 I think it was, I believe it was the one Burt was on, arranging for Marlene Dietrich. That was like a big thing! I told my friends, “My dad is going to be on The Royal Command Performance and, bigger still, The Beatles are gonna be on it”, you know. Only recently did I realize it was the same one Burt did with Dietrich. They were all on the bill together. All this music was rattling around in my head all the time I was growing up.

Q: I remember you sending one of your songs to Sammy Cahn fifteen years ago.

EC: I did.

Q: You’ve been trying to crash this party a long time.

EC: (Laughs.) I think the thing about it is that rock ‘n’ roll had two effects on music. One was one of tremendous liberation, and the other one was a license for a lot of idiots to decry the efforts of more craftsman-like writers, and to suggest that there was a barrier that came up in 1955 like the Iron Curtain going down, and everything after that is justified, and everything before it isn’t. And in recent times, as you see, a lot of kids now are hip to swing music again, and the fact that they may understand it in a kind of cock-eyed fashion or whatever it is they focus on for music, from the richness of musical history, I think it’s a healthy thing that they don’t think just rigidly in terms of like one strain of music to the exclusion of everything else. Because the great thing about growing up in England in the sixties is that you could listen to The Beatles synthesizing Chuck Berry, The Everly Brothers, The Miracles, and then on the same radio station there would be actual Tamla-Motown artists; and then Burt’s records came out, and all of this stuff is going in my head at the time when I’m just getting my musical ideas. It’s all going in my head like at a million miles an hour. That’s the most exciting thing. It is deeply rooted.

“Please Stay” is the first one that I cut on “Kojak Variety”. The Drifters originally did it. And Zoot Money and The Big Band did a cover and had the hit in England. There were two other versions and I’ve told Burt he always got his hits stolen out from under him in England. And, because my family is from the Merseyside, we were very loyal to the Mersey bands. It was a big deal that people from Liverpool got successful in show business in the early sixties. People cannot imagine what it was like for people in Liverpool to suddenly find kids from Liverpool being on television in England, let alone in America. The Beatles thing was so out of proportion with everyone else’s fame that people were very loyal. Any group that came from Liverpool. My family and their friends who were also from Liverpool were really rooting for Cilla (Black) when she came out.

Q: Well, you can do panto for thirty years after one hit over there.

EC: Yeah. And they still do! (chuckles.) I’m sure from Burt’s point of view, making killer records on these songs with Dionne Warwick and having somebody copy them, ya know... But we didn’t know that, you see, because we didn’t get to hear them for at least six weeks. We had to wait six weeks to hear the “real one”. I guess, as you get a little older and more tuned in, and as I’ve gone back and listened to them all, I can hear how crude the transcriptions are at times of some of those great records. But on the other hand, you can’t help but be in love with them, because it’s the first time you hear a song. When I hear The Drifters’ “Please Stay”, I sort of go, “Well, I can see it’s great, but the Zoot Money one was the one I fell in love with the song for.” I can’t help it, you know, even if it’s a corny version. I happen to think it’s a pretty great version.

Q: Well, it was pretty obvious that both of you had a great time and really delivered with “God Give Me Strength” for the “Grace Of My Heart” film and soundtrack album. That’s a fuckin’ great song. In “Musician” a couple of years ago, you discussed the genesis and collaboration of the song and songwriting process for this one tune. What was the pre-production and songwriting process like for a whole album of Bacharach/Costello songs?

EC: The title was taken from one of the songs (“Painted From Memory”), not to place any more importance on that song, I think. It’s a nice title. The pre-production really I suppose was the writing period. I suggested to Burt we pick up the thread from “God Give Me Strength”, and see what happened when we got in the room together, ya know? You probably know we didn’t actually work in any kind of room together until we made that record. That was done by fax machine and telephone because it was the only way to do it because of the production deadline. If you’ve seen the film, the song is performed and obviously they had to have it in time to film it. So that was the only way. I was on tour in Europe and Burt and I had five days to do it. It was very quick. Having written that song that seems that strong, ya know, and having made a record of it, I thought it was fantastic.

Q: How did the project come together? From what I’ve heard on playback, it’s make-out music for the next millennium.

BB: We didn’t really get together until we were in New York. I had written the orchestration in Florida, or wherever that was.

EC: That was the first experience in working together and seeing how, for me you know, the things you sort of assume from listening to records and seeing Burt work, and seeing how he’ll take a cue that was such a vague suggestion on the demo that I had written down at home, and then it would be really defined. Burt had written the introduction figure, which was an additional figure in the composition, which set up the vocal, because whenever I played the song to myself, it was very hard to get started with the song. To physically just start singing. It was actually quite a difficult song to start singing.

BB: After that, we got together five or six times for writing sessions in different places like New York or in Los Angeles. And we got to know each other and the work process very well. Each time we got together we’d spend a lot of hours. Four or five hours a day. We were working a lot with two keyboards. Because very seldom have I written with somebody who is a musician, a composer as well as a lyricist. So we usually sat at two keyboards, sometimes like in New York at a hotel we just had one keyboard. But out here in L.A. at my studio, Elvis would sit at the acoustic Yamaha. We’ve collaborated on the music. So that’s very different than me writing a piece of music and giving it to a lyricist, or taking a lyric that has been given to me and setting it to music.

EC: How often have you done that in the past? Were there many songs?

BB: No. I wrote three of my songs with Carole (Bayer-Sager) and Neil Diamond - Neil would play guitar - and some songs with David Foster...

Q: Elvis, when you write songs now, are they mostly originated on piano, as opposed to guitar earlier in your career?

EC: I have no particular certain method of doing it normally. In fact, in recent times I think, I’ve become less lyrically driven, and certainly less interested in lyrics the last few years, until working on this record presented a new kind of challenge. For me, I was quite happy with the thought that if I was going out on my own I could have been quite happy making a record with no words on it. My ambition is to write no words at all. It’s to be a good enough musician to convey with the same kind of clarity and, if I’ve ever achieved it, any kind of eloquence with words, in music without the words.

So that’s a good thing to have because it’s a distant horizon. And I know I’m miles and miles away from it, you know, and so that’s the reason I keep going because my interest is to not write any more words eventually. So I know I might be years and years away from it, or may never get there, but it’s a good ambition to have, because it makes me distrustful of just reams of words, which I’ve had a tendency to write.

There were lots of words, and I know there’s a lot of words in a lot of my songs, and what I’m getting to is the discipline of this record, and even with the music that I wrote for the collaborative songs, you’ve got to understand that the formula of composition is different on every song on this record. There are two or three songs, I think, entirely Burt’s music. There are some where the larger part of the initial musical information came from me, but then we’d work on it together, and there’s quite a good proportion where it would be accurate to say it was more or less a dialog in music, section by section, where one of us proposed it. We may have worked on it together, but obviously the process of making it work together in a flow came from sitting at the keyboard together.

BB: That is very different for me.

EC: That is totally different from anything I’ve done.

Q: I know you used to write your songs on guitar up until “Imperial Bedroom”, like with “Boy With A Problem”. Then you started writing on piano because you once told me you could get lost writing more on keyboard and piano.

EC: Yeah. On this record, there’s only one song that has any information in it at all, any initial musical structure, derived from the guitar, and that’s some of the music in “Painted From Memory” started on the guitar. Everything else that I’ve written was based on the piano. And even “Painted From Memory”, almost as soon as I showed it to Burt, the key changed, because it wasn’t a practical key for singing. And once it was on the keyboard, I never touched the guitar again...

I can recognize there is a certain characteristic to the songs where one of us may be the dominant writer of the initial music, but with the exception of the songs that are almost wholly Burt’s composition, they’ve all stopped having the sense of who wrote them, because we worked on them together so much I don’t even think about who wrote what. All I know is that once they were on the piano, they stayed on the piano. Because, as limited as my abilities are, I could see it in front of me, and when Burt would show me something as a change to maybe something that I proposed initially, and hand it back to me with an amendment to the harmony or a rhythmic change, there was no point in trying to put it back on the guitar. There are good songs we’re happy to put our name on. I think the collaborative thing, I think it’s true, and I’m just as inclined to say, “I must do that vocal again”. I mean, in “God Give Me Strength”, for example, there’s a crack in the voice in the bridge that I wanted to fix, and Burt said, “Leave it”. And now I’m so glad he made me leave it there because I realize he was right saying it had a feeling, and if you fix every bit of feeling out of it, that’s a danger.

BB: I started making my own records out of self-defense. To protect. Because I think (years ago) I ruined some good songs, because I trusted some of the A&R people. I thought they really had to be good, or they wouldn’t have that job. If I had a three bar phrase, then that really worked as a three bar phrase. It’s like, let’s take a song like “Wives and Lovers”. Thank God nobody suggested it in the A&R department, but if somebody had said, “We’ll get so-and-so to record it, it will be a single, it’ll go in the movie,... but you’ve got to put it in 4/4...”

EC: You had to wait for Sinatra to do it that way! (laughs) Didn’t they do it that way?

BB: Quincy (Jones) said, “Sorry, we did it in four because they said they couldn’t play it in three!” (smiles)

EC: You can’t imagine what led to that decision to change that.

Q: Elvis, as the record developed, how did you like Burt as a producer?

EC: I see it as we co-produced the record and really worked as a team. Before we left the last writing session, which was very fast and furious, and the last week there were some lyrics for me to put in place that I had just finished. And some of the songs had some fairly drastic changes, and they were mainly with real consideration to their being recorded. Because when you’re writing you can allow the song to ramble a bit, and then you start thinking, “Now we’ve got to take this song out in the world. How are we going to get back to ‘A’?”, or “How are we going to get back to the hook quicker?”

There were some songs, like one that was nearly seven minutes long in its original form, and obviously that wasn’t going to work, so there was some serious editing going on in the last week at the same time as the considerations of the orchestration of things started coming in. Because you start really thinking about the reality of it being a record. And since then, we’ve sort of shared the responsibility in the studio. Burt’s written all but one of the orchestrations. But I mean, it’s not as if I didn’t know what they were going to be, because he’d talked them through with me and said, like, “This is going to be a basic flute...”

BB: I’d send Elvis a four-line sketch, you know, which was totally comprehensive.

EC: Once we got into the studio, if Burt was at the podium with the orchestra, I’d be behind the desk. My ears are not trained for all the inner parts of the string writing, but you can tell if it’s worth consideration. And then Burt and the concert master come in and review. Sometimes there were edits to the parts, sometimes you realize you can get by with less writing and I think with additional orchestration, there was an instinct that we followed, which was a very sound one, to always be paring the parts down to the minimum, where they are the most effective. Because, when your ear is not used to them all the time, that surprise and pleasure of hearing the re-entrance of something, that would go on. And also those things sometimes being a reaction to the track we had laid down. You do the track and that changes the character of the orchestration. That’s what was good about the musicians giving us their fullest attention and concentration and responding with, you know, sometimes working with us where Burt would suggest like a different bowing, or sometimes a different effect with something like a harmonic, where you want it really precisely tuned, or a specific effect with phrasing, or a tonal thing that the horn players can give you. I mean you’ve got to have players who are really prepared to work with you.

Q: How did the players for this album come together? I know both of you have worked with Jim Keltner before, and Greg Cohen plays with Tom Waits.

BB: Elvis wanted to put a core rhythm section together, which I think is a great idea.

EC: It gives it personality. I really loved the band that made “God Give Me Strength”. It was an excellent band, ya know. But as we had agreed to make the record here, there were technical reasons for coming here. There were all sorts of reasons why it seemed like the best venue to record. One of the main ones was being in this studio (Ocean Way). The ability for Burt to be based out of home was very important for the amount of work. It made sense.

BB: I could really appreciate the way this whole thing got scheduled out. Because my wife is in Greece with her mother during this recording, and we have two small kids, and a parent being in that house.

EC: And Ocean Way is a fantastic studio. The former United Western and United recording studio.

BB: I think the two core players, Jim Keltner and Greg Cohen, besides Steve Nieve, who has worked with Elvis for so long, so that’s a center. You’ve got Steve, Greg Cohen and Keltner.

EC: That was the band that played on more of the stuff, and Burt on piano. Steve taking care of the second keyboard parts, which were integral to the glue, whatever the part was. It could be a tack piano, a synth, or an organ part, or a string thing laying out the cue that would later be replaced in some cases. Bells and things that were essential for timing, that had to be played. Not as dramatic a role as he’s done on many of my earlier recordings, but a really important, discreet role, I think.

And also, the responsibility that, in a song that was very delicately poised, like the title track, where there's no drums, the necessity was for Burt to conduct. Even though it was a tiny ensemble with two guitarists, George Doering and Dean Parks. So, Steve played piano on that track with Greg Cohen on bass, whom I’d admired and briefly worked with once on “The Big Lebowski” soundtrack. He plays great upright bass, even though he only played it on one song in the end. I think he gave a lot of thought to the character of each instrument for each song. He used a lot of interesting, old quirky basses that didn’t have that modern hi-fi sound, but more like the sound you get from a string bass but with the clarity and point that you want from an electric.

I had a feeling, and I said to Burt, that the combination of Greg (Cohen) and (Jim) Keltner, who had worked together on a couple of projects, that combination would be very important because with the amount of slow tempo on this record it was essential that the form and momentum be maintained. And, in my opinion, Keltner is the premier drummer in the world for slow tempo music - if he isn’t the premier drummer in the world, he’s certainly among them. And for the propulsion of slow tempo, I think he’s almost unparalleled.

Q: Studio question. Why Ocean Way?

EC: There’s a lot of reasons for recording here. They have a great stock of great microphones. They have a great board in Studio 2. And as it now turns out, a great mixing board in 3. And Studio 1 is an excellent room for string recording. It has a great sound. We also tracked one very spacious ballad in Studio 1, where the size of the room I think was a positive advantage. And if you’re asking me, it’s absolutely analog. We mix to analog. I like that Neve board. I like those tape machines. If I had my way I would master to quarter inch, let alone half-inch, ‘cause I like tape compression. DAT is used purely for backup. Analog over digital. It’s no contest for me. I did do one recording that was quite good on digital.

Q: Can we discuss recording the vocals for this record? Did Burt impact the direction of the vocals or your specific delivery on the songs?

EC: I think the ‘vocals’ come from the compositions. Just the way the tunes lay and the amount of space there is in them. ‘Cause it’s naturally the way they’re paced, and rhythmically the movements that they make, particularly the short phrases followed by longer phrases, not consistent like in a pocket with a very insistent rhythm.

BB: Nothing is crowded. But then our intent was not to be crowded in the composition, or crowded in what was gonna be jammed in on the color, the orchestration, things that would be too busy behind.

EC: I think that’s very true. I found that I’m using certain changes of tone, certain ways of chopping notes off rhythmically and tonally in response to the music as I hear it. There’s a naturalness to the certain way that you use your voice and sometimes when my voice becomes too characteristically the me of years gone by, it doesn’t fit. My voice gets a little raw and I had to sing in a more musical way, with more tone. There’s no shouting on this record to speak of (laughs). And it’s true to say that Burt favors softer singing and I lean towards singing softer and more melodiously as Nature will allow me, which is also nice.

BB: For me, it’s always - if it can work - if you have the song, and you have it intimate, then you have the capacity to explode on a level that is very wide scope.

Q: How does a song in the early stages suggest a string arrangement to be included on the track?

BB: I’m very conscious of too much strings on records. It’s an invasion of some territory that I’m very allergic to now. First of all, you’ve got to have a lead going in. Elvis can sing and he’ll make things sound extraordinary and big with drums, piano, bass and guitar. Like on the song, “I Still Have That Other Girl”. It stands up. His voice stands up the whole record without strings. And it’s very large at times. Very wide scope. So, when you know you have a situation that plays, then you can take the strings - and I overwrote the strings a little bit, I didn’t realize I overwrote until I heard ‘em and then I realized, “...hey, let them play five bars and let’s bail. Let’s bring ‘em out for that sweep down, and then, right on the modulation...” And, you know... It’s like you have a great smile but you can’t use it all the time. Drop it in.

EC: It’s such a great moment when we took them out for the first time, ya know. The track didn’t fall apart just because we introduced them with power the first time, they went away actually on the hook, exactly where most people would introduce them, and realize that the rhythm section performances were strong enough. So in that way, we didn’t have to drop them out at the more typical place... If this record is going to be played on the radio it’s because it doesn’t sound like everything else. Not because it sounds like everything else.

Q: Did you stretch out more vocally? Do the songs and words demand that?

EC: Yeah. Whether they demand it, they present an opportunity to do it. And it feels possible to do it in the studio. I know from singing “God Give Me Strength” while doing a tour of opera houses in Italy with Steve Nieve, very nice, very good singing halls in January. And though it was a tremendous temptation to play piano versions of the songs we’d already finished, I wanted people to hear these songs the way Burt and I were going to record them. So I didn’t debut anything from this record, even though I was dying to see what would happen. But “God Give Me Strength” was already out there, so we played it and every single night it stopped the show. I mean, stopped the show. Like we couldn’t play the next song because people wouldn’t stop clapping. I’ve never experienced anything like it, because it was such a singers’ hall, the effect of the song had this amazing response every night. It had easily the best response of any song all night, even better known songs I’ve sung for 20 years.

“On top of which, three nights out of the tour it was literally me asking the audience very politely to stop clapping. And I don’t know if we’d hit the mark on it or something. I had never experienced that. And also, I’ve come to grips with singing that song, a bit more than, I guess even the recorded version. So you get to the situation where you feel, “I just want to get these songs on a stage to see where else they can go”, once you get that adrenalin.

“The first song that we performed from this record was on Burt’s TNT “One Amazing Night” television special, and we did “This House Is Empty Now”, where you came to the mixing session. To be honest with you, it caused the biggest problems in getting the recorded version, simply because I had never heard the arrangement before the day. I’d heard a rough sketch of the arrangement about a week before I came over to New York. We rehearsed it the night before. We did a dress rehearsal and the show was the third performance. And it’s a pretty damn good performance. And I couldn’t sing it better in the studio. It took me... We finally sang it last night. It was one of the few vocals on the record that I overdubbed most of the way. Nearly every track on this record has the core performance. And every track has some element of live singing on it.

Q: A couple of the songs have some female backing vocals. You’ve done that before, like on “Every Day I Write The Book”.

EC: Yeah, but the background vocals before were written as more call and response kind of relationship, or in Nashville (for “Almost Blue”) they put them on after we left, ya know. “It’s Been A Good Year For The Roses” and the choir comes in, “Roses”. The way they do it there, like a machine. That was the fun of going to a recording experience like recording in Nashville, it’s that you get the things they do there. You don’t go there and expect it to sound like something you would do in England, or otherwise we wouldn’t have gone.

With the vocals you’re asking us about here, the parts are written as part of the composition. They’re not additions. In the song, “Toledo”, the lyric is about a guy who comes home and he’s been unfaithful. He’s trying to delay the call of confession. And at the crucial moment, at the end of the chorus, after he’s said all this stuff about Toledo, the girls come in with me and sing, “You hear her voice, how could you do that?” For me that’s the bit that pays off the whole chorus. But that’s not something like an afterthought. It was one of the last things that was composed in the song, but I remember the day we were working on the song and trying to finish it off and Burt said, “Maybe we should have that before the re-entrance of the flugelhorns.” And I wasn’t sure at first, whether we needed another section in the song. It seemed like it had quite a lot of sections. Now it’s my favorite bit in the whole song and sometimes you just have to trust. Now it feels like the song couldn’t live without it. At first it would have seemed like, “Wow, why would we delay that?” (the re-entrance of the flugels.) And now delaying it with something that strong emotionally is the killer. It’s the thing that makes that bit work.

Q: Is doing this collaboration a lot different than other joint efforts where perhaps you work even harder at it, or allow things to happen?

EC: I think we’re both inclined to examine things in great detail in the writing. My collaborative experiences are quite broad but they are very, very different in objective, ya know. When I was writing with The Brodsky Quartet, that was such a different form of music for me and I’d only just mastered writing music down, which was a necessary part of collaborating with them. So there were all these things that colored the way the music took shape. Other collaborations I’ve done have been much more grabbing a spontaneous feeling of music with a couple of guitars and rhythm motivating everything. This is a very deliberate thing but you have to have the initial inspiration and a strong thought on the first kind of musical thing like in the first rehearsal. I think I may have thought of opening music for one song that ended up on the record and Burt would have put the opening music on another song. But if you were to play that tape now you probably wouldn’t recognize those songs to the finished thing. They've gone through a lot of work.

BB: No demos, no rehearsals. I like to believe we know basically that we know what we’ve got and what’s going to work and what’s not going to work before we hear it.

EC: We cut 13 backing tracks in eight days. That was like nine songs that we got first time and 2 that we did two remakes in order to get the rhythm settled in the way we wanted. It’s a pretty good ratio considering there were no rehearsals.

BB: I don’t agree with something Elvis said before of just having something be totally sufficient as melody without words. For me, it’s gotta have words on it even if it makes no sense. I’ll put ‘dummy’ words just because it gives a different shape.

EC: Isn’t that funny, though? That’s a really good dichotomy. You don’t write words, and I’m probably better known for words than music and that’s why my distant horizon and ambition... Like, how would I know we’d be making this record together? If somebody had said 20 years ago we’d make a record, I would have thought it would be a completely fanciful thing. Not ‘cause I wouldn’t have liked to do it, but I would not have conceived of the circumstances where we’d meet and we’d find a place where we could work together. That’s a great thing. But to have a true ambition that is deeply personal, to have a distant horizon, something maybe you can never achieve, keeps you striving for something - it’s just because I do write so many words that I kind of say, it’s the opposite thing, it makes me write better to think that maybe I could make it stand up without them. I know realistically that’s never gonna happen, or certainly it’s not gonna happen anytime soon.

BB: And then Elvis presented me the role of Bill Frisell going in and taking these songs and making an instrumental album, and trying to wear an objective hat, I would find that terrifying.

Q: There’s sort of a later companion album of instrumentals culled from your new tunes that follows this release?

EC: Yeah. At the same time as we’ve been finishing this record, Bill Frisell was commissioned by Verve to write orchestrations without the use of vocalization, although there may be a couple of guest vocalists on the record. The idea is they will be an investigation on a musical level, ‘cause obviously it’s for Verve, it’s largely with a cast of musicians one would call jazz musicians, broadly speaking. Frisell himself, Billy Brooze (spelling?) , Don Byron, Curtis Fowlkes, Brian Blade, Victor Kraus, Ron Miles on trumpet. It’s a very rich band. It’s slated to come out a few months after our record. It’s not something that will have the same kind of audience even. I don’t think it wants to have the same audience, or otherwise we’d be in competition (laughs). I think it’s a big compliment we’ve been paid. The idea was conceived before anybody really heard this music.

Q: In addition, there are a lot of spaces and holes in the music, and at times a pretty smooth jazz feel to the instrumental tracks. In the mid-’60s Jim Keltner was a local jazz drummer and I can hear some traces of that in his playing on your recording.

EC: It’s in the mix, isn’t it? It’s a frame of mind, I’m convinced. I think that’s why Frisell is able to make the record on this thing. Not so that he can take these songs as a taking off point for a selfish improvisation, but it’s a frame of mind and he’s found sympathy with it. I’ve heard a rough mix of a few things and there’s a sympathy that lies just in the relationship between instruments that you don’t find in rock records.

There’s space in it and also the way it’s recorded. It’s actually a recording of music being played in a room where the balances are real, unlike most rock records where it’s all about like crushing things together for the effect of that tension.

It’s not to say it’s bad to cram things together, but you’ve got to know what you’re doing and you’ve got to cram them together in a smart way.

Q: I enjoy hearing your voice placement inside the music. Perhaps the loose grooves and punctual drum/bass scenes lend themselves to your vocals being displayed a little differently than I’ve ever heard you. And I know Burt has a lot to do with that aspect. Right?

EC: Most of the time, Burt’s comments are to put the voice in the real relationship never louder than it could really be. Where on other records I’ve tended to push the voice very far forward or bury it with an effect, for the kind of story that can tell. The weird thing is the way we worked. [Engineer] Kevin (Killen) will get the mix to a certain stage and then we’ll both try and arrive around the same time - one may arrive before the other - make some comments about balances, and invariably, if there’s been any need to adjust the balance with the voice, it’s to make it come back a little bit so the track comes around it.

Then the process that we follow, and I hope Burt doesn’t mind me telling you, is that Burt will take a cassette into the studio where he has his boom box setup that he really trusts, and I’m the same. I’ll go out to my car. Something you’re used to. Then you’ll know to turn one or two words up, so in other words, it’s at the very minimum that it can be before it’s too quiet, so that it sounds intimate without being artificial. And then you will spot a word that we’re losing behind the accompaniment. And that’s some of the most detailed mixing I’ve ever heard. The most acute sense of the placement of the voice. And it’s really got the result. That’s the thing I’ve learned.

I have a tendency to go the other way. I scared the hell out of a classical engineer at Abbey Road one day when I did a thing for John Harle’s record, because I was riding my voice the way you do in pop, whereas in those classical recordings, everything stays. They create the sound. And I said, “I don’t sing like that. I sing on to the mike. I don’t sing into the air and the microphone catches it.” And I told him, “You’ve got to ride certain things I’m doing, or otherwise you’re not actually getting what I’m creating.” And he was trying to move it a quarter of an inch. And I’d say, “No, like this...” Pushing it like an inch. He couldn’t believe it. He’d never seen anyone touch a fader that much (smiles). But that’s just depending on what kind of voice you’re using.

Q: Burt, what’s the wisdom in multiple takes with a vocalist?

BB: I’ve gone 30, 40 takes. On Dionne’s first record, I had her on take four. Maybe the difference now from what it used to be is that I know I’m going to be O.K. at 95 percent. You can make yourself crazy going for 100 percent. It’s not about what you get, but what you’re gonna get as a result. Something is gonna be at fault in the record. The guitar player played great but you don’t do it all at the same time. Played great on the one take, but the drummer made a mistake, or didn’t play as good, or didn’t go to the ride cymbal when you hoped he would. Then the balance shifts and you didn’t get the performance on the next take. It’s about compromising. Get as close to... I learned something from Don Was. Just talking to Don, maybe six or seven years ago. I was doing a lot of stuff on synthesizers and drum machines. Don said, “It’s not so important that somebody makes a mistake, if the track is there and the song feels good. If the song is there and the vocal performance is there, that’s it.”

EC: We spent a lot of time on my new balances, without the concentration on which we wouldn’t be happy to consider. But the whole reason for doing that is so that nothing distracts from the basic thrust of the thing, the story that’s being told, and that the vocal performance is the best it can be. I would idealize certain phrases in songs. And there are still things that are on the record that are not the way I originally idealized singing them. On the other hand, what I would lose in changing that one line would be the necessity to maybe fix the two lines on either side of it, which would then completely change the picture. I would idealize one tail of a phrase to lose three lines. That’s idiotic, ya know. It’s not settling for less, it’s just actually making sure you don’t perfect yourself right out of a soulful performance.

BB: I’ve seen great singers who I’ve worked with keep going and taking a word again and again...

EC: Nashville producer, Billy Sherrill, did tell me one great thing about working in Nashville. He used to have to go in and put the d’s and hard consonants on the ends of Tammy Wynette’s words, because of the way she sang them. Like adding ‘-ng’ and ‘da...’ Like going in and doing ends of words. She sang in such an open way and so attractive but...

Q: I wanted to ask Burt how he felt about Elvis as a singer.

BB: He’s O.K. (giggles). There’s no one who sounds like Elvis. There’s immediate impact because you know it’s Elvis. It can’t be anybody else. Also, high charge and enormous power and very emotional voice and a kind of thrilling voice. He did a vocal the other night and sang himself out. I could not believe it. Top to bottom. He sounded great. A very durable voice. Like a great machine tuned up.

Q: Is there a loose theme, or anything to the sequence of album cuts presented? Why are the songs in this subject specific order?

EC: There’s all sorts of reasons. We mixed in sequence. Like “In The Darkest Place” leads into “Toledo”. “I Still Have That Other Girl”. “The House Is Empty Now”, followed by “Tears At The Birthday Party” and “Such Unlikely Lovers”. That’s very clear in my mind. The main one really, is one of trying to achieve contrast without them jolting the listener out of any mood or reverie they might have succeeded in creating. I have been guilty of using shock tactics on records on a number of occasions and I think it was justified for the kind of records they were. But for this record I think it's very important that the moods of some of these recordings are quite delicate without being weak and it would be absolutely idiotic to undermine the work of three or four minutes of musical development, composition, arrangement and performance by putting the next song that could just completely throw you out of that mood.

It carries you over. “In The Darkest Place” is a fairly serious opening track. It’s not promising a happy-go-lucky “Polkadots and Moonbeams” kind of scenario. Yet the second song, “Toledo”, though it’s quite a sad story about infidelity, has this feeling that makes you sit up a little bit. As they have come into shape in the recording, I wrote them down and proposed them to Burt, and as we are putting them together and mixing them, there are always considerations that, like, If you are sequencing a record, I think, in these songs the key relationships are much less important than in almost any other record I’ve worked on. Simply because the musical development in each song is so pronounced that the sense of one tonal relationship that is maintained throughout the whole song is very rare. I don’t think of any song that stays in one place all the time. There are implied modulations, actual modulations, all sorts of things that happen.

If you have a rock song based around four chords and you put four songs back to back all in G, you’re gonna hear it. Normally I would avoid that. Secondly, if you have used orchestration with as much variety as we have, but nevertheless all in one sound world, it obviously trips you up if you have a device that you use to great effect in one song and even something which is remotely similar in another song, to have again back to back. So there are those considerations that govern it that are purely practical. Beyond that, those things are secondary, very, very secondary to the mood, the lyrical theme and the emotional impact that is really created by tempo, harmony and rhythm and therefore it is important that you don’t wear the listener out. The first song is a definite challenge. We’re coming into a place which is of our own creation. We’re not making any allowances for it being like anything else. The next two songs following the opening are short enough to be absorbed very swiftly. Then “This House Is Empty”, a long ballad that goes through a lot of transitions. Then we’re back to two songs that move quite swiftly, though they have their own internal story and world. And then another ballad. In that way the sequence works itself out, doesn’t it? It’s quite obvious.

Q: One thing about songwriting. Do you title the songs before you write them, or add that after the initial composition?

EC: In a few cases like “In The Darkest Place” I had the title and opening phrase. They came to me simultaneously on a plane. Usually some thought and melody, and by the time it gets to the piano and through a few of the transitions working on it together, it’s an utterly different beast. Some of the songs changed titles or personality. Most of them really were written in response to music. That would be more truthful. Like “Such Unlikely Lovers” instantly was a song about people walking down the street and it had a romantic implication and I knew it was a visual image I never experienced with music before. Because I’m not used to having music thrown at me that way. That imaginative. I didn’t have the exact words, but I knew it had something to do with that. As it developed into an area which was about a chance encounter that led to some change in their lives. So it seemed natural to develop the idea into “Such Unlikely Lovers”.

On most of these songs, the words are simple enough to keep them comprehensible and serve the music clearly, and at the same time still individual enough to me that people wouldn’t say they can’t recognize any of my personality. There aren’t any trick phrases or back flips in the words. There are some individual turns of phrase but I think sometimes by listening to the music and listening to what the music is telling me... For example, in the last verse of “My Thief”, Burt played me this beautiful melody and I don’t think unless I’d had the spacing of that tune I would have ever come up with these words. The song is about a man who has a haunting dream of a woman who has left him, and he’s asking for the dream to recur, because that is the only place where she still exists in his life. It’s a fairly tortured thought. It’s not an unpleasant place to be, but it’s far from an optimistic song. And he’s living with this fairly tormented thought and in the final verse it says, “I’m so drowsy now I’ll unlock the door.” So he’s welcoming a ghostly kind of presence or however you want to interpret that.

The spacing of the music I wrote, and the idea that is contained in the song is explained to some degree in the chorus and it says, “What fades in time will hurt much more”. I would have never written that if it hadn’t been for the music being spaced the way it is. And it is very true. The thing that fades from your life will hurt you more than having something that reminds you that you once felt something, because ultimately all the songs on the record, however sad they may be, are about the necessity to feel something and the music hopefully is about trying to reach to have those feelings. To be alive means to have feelings and to be alive sometimes means pain. You can’t have life without any pain. You can’t have experience without any pain. So “What fades in time will hurt much more” is saying, “To have no feeling is the worst possible thing”. It’s not saying it’s a profound thought, but it’s one that occurred to me in response to the music, and I never would have written those exact, simple words. It’s far from a typical phrase of mine, yet it’s my favorite phrase in the whole record.

Q: I heard a couple of things with some light brass or some trumpets.

EC: There’s a vocal quality to all of the solo playing. All of the figures are played on instruments that can continue the emotional content of the song. I don’t think any of them are used for impact. Strings are used to support the increase in emotional temperature and, you know, I’m a frustrated trumpet player. I let the side down. I’m the third. My father and grandfather were both trumpet players and I was supposed to follow. I tried to pick it up. I love the trumpet and I love the flugelhorn even more. Our original intent was to write 11 songs or however many songs as good as “God Give Me Strength” (included on the CD) but different. So we just achieved that.

BB: And you never know it until you get to the stage whether you succeeded. (Harvey Kubernik is the author of 20 books, including 2009’s Canyon Of Dreams: The Magic And The Music Of Laurel Canyon and 2014’s Turn Up The Radio! Rock, Pop and Roll In Los Angeles 1956-1972. Sterling/Barnes and Noble in 2018 published Harvey and Kenneth Kubernik’s The Story Of The Band: From Big Pink To The Last Waltz. In2021 they wrote Jimi Hendrix: Voodoo Child for Sterling/Barnes and Noble. Otherworld Cottage Industries in 2020 published Harvey’s Docs That Rock, Music That Matters.