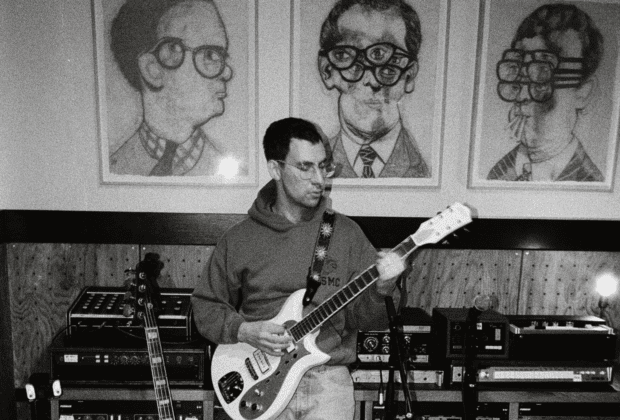

Musician, producer and eminent East-Coaster Jack Antonoff has had a relationship with music since he was old enough to know what it was. Like many successful artists, he began to play in bands as a teenager and was always comfortable taking the helm to guide and shape projects. That penchant for production has served him well and he’s played musical midwife to a swathe of artists that includes Taylor Swift, Lana Del Rey and Sabrina Carpenter, to name-drop a few. His efforts have earned him a staggering, Quincy Jones-level 11 Grammys, three of which were for Producer of the Year for the past three years running. Accordingly, he’s a member of an exclusive club, the members of which could fit around a single, self-luminous table.

The morning Music Connection spoke with him, he’d just been invited to join Swift on stage at London’s Wembley Stadium. There he helped mete out melodies to the intimate crowd of nearly 100,000. He happened to be in town for the kickoff of the European leg of his band Bleachers’ tour later the same week. Rarely idle, he also logged some production time at Sleeper Sounds while in the cockney capital.

Beginnings

“Production was always something I did,” Antonoff recalls of how he waded into the trade. “[But] I didn’t know it was producing. I always thought ‘I’m a songwriter, an artist and I make albums.’ Probably because so much of the folklore I’d heard about music came from the '60s and '70s. You hear all of these stories of David Crosby going to somebody’s house, Jackson Browne and Joni Mitchell are there and they write these songs. The combination of all that mythology and then growing up in the New Jersey scene, it was always a part of me that everyone helps with each other’s music.

It wasn’t until I got a little older that I realized that I was producing music. Someone would play me a song and I’d think ‘There’s gotta be strings here. It’s too fast. We’ve gotta be sure we record it this way.’ Life is so unsure, but the one area where I have complete confidence is when I hear things, how I feel about them and what I think should happen. So I always did this. And as I kept touring and making records, I began to see that I was producing them too.

“It’s been made clear to me what an anomaly I am to some people,” he continues. “I understand that these are all separate things. Some people love producing, some love writing or being on the road. But this spectrum has always been what I’ve done. I’ve never seen it as separate pieces. Through all of this, there was no time when it wasn't just music. I heard music all day and I wrote it in my head. I didn't know I was writing or producing. The world told me that later.”

Creating to Connect

To Antonoff, the appeal of production and of making music in general lies, to a great extent, in deepening his connection with his listeners and nurturing his own emotional well-being. There’s also the aspect of becoming so engrossed in what he’s doing that he’s nearly unaware of anything else, not unlike a meditation, a mental state that psychologists often refer to as “flow” and what most everyone else simply calls “being in the zone.” As he explains it, “It’s something that comes naturally to me. It’s like a language; like a way of communicating. If you can find things where you feel peace, comfort, excitement, you feel alive within them. It’s never crossed my mind that I wanted to be anywhere else.

I’ve never had a moment in the studio or on stage when I’ve thought ‘This kind of sucks’ or had a thought outside of what I was doing. In every other aspect of my life I can be anxious, exhausted, nervous or unsure. So if you’re lucky enough to find a space where all of the poison of being alive doesn’t exist, then that’s where you’re meant to be. I feel far away from the darkness. Then when I leave, the darkness is pretty close. It’s not a bad thing; I’m not terribly depressive. Life is challenging and stressful. You have to work so hard and put all of yourself on the line constantly to even get through it or to exist.

That’s everyone’s experience and if someone tells you it isn’t, they’re either lying to you or to themselves. So we look for these moments of purpose or relief—suspension of all of the intensity it is to exist—then you’ve crested to another plane. To me, that’s the point of life. I have no complicated relationship with the heart and soul of this work. I'm constantly excited by it, mystified and drawn back to it.”

Finding a safe space

Any artist is fortunate if they have a physical place of peace where they feel supported and safe to create. Antonoff finds this vibe in all of the four main studios at which he works, the most notable being New York City’s Electric Lady. “That’s home,” he asserts. “Everything kind of goes through there. At this point in my life, it would be borderline impossible to not have something at least pass through there if not [be] made there completely. Emotions and sonics fill spaces and then you start to understand them. I know that room. It’s kind of the attic where Jimi [Hendrix] lived. I also know my room at home and in L.A. It’s like the same way that I know my wired iPod headphones. I check my mixes on them and can understand quickly what I need to do.”

Essentially, Antonoff’s four main work spaces are Electric Lady, his Brooklyn home studio Rough Customer, a more rudimentary one at his permanent home in New Jersey and then one built recently in Los Angeles. John Storyk is a renowned studio architect whose first design was, in fact, Electric Lady. He’s since planned thousands of others, notably for Alicia Keys, Jay-Z and Green Day, among others.

It was Antonoff’s love of Electric Lady that prompted him to enlist Storyk’s help with both Rough Customer and additionally with his longtime engineer Laura Sisk on his L.A. setup. “I was really nervous when we built my L.A. space,” he recalls. “There’s an element to a great studio that you can’t really put your finger on. It’s not about how perfect the soundproofing is, it’s not about the gear. Some rooms have that magic.

“I did everything the way I saw it in my head,” he adds. “The studio is one of the most comfortable spaces in the world for me. But I was nervous when I first walked into my L.A. place because I worried that it might not be a good vibe. I started recording and that week I’d written and recorded some Bleachers things that I loved. Lana came in and we did some of my favorite things I’d ever done and Taylor and I finished ‘Fortnight’ there. After all of that, I realized that the place had magic. Anyone who's ever built a studio knows that if you build a place outside of your home studio, it creates anxiety about its functionality and magic.”

In addition to these sonic spaces, Antonoff often makes regular visits to Conway Recording Studios in the heart of Hollywood and Henson Recording Studios a short stroll away… if anyone were to ever actually walk in Los Angeles. But he’s most comfortable on home turf back on the East Coast. “I go straight to how I feel when the plane lands at JFK or Newark,” he notes. “My shoulders drop and I’m home. Anywhere else I sort of tense up and get ready for battle.”

Challenges and peak moments

Bleachers released its fourth record—the self-titled Bleachers—earlier this year. Antonoff finds that the song that was most challenging (or of which he’s most proud) changes over time. “But in this moment it’s ‘Modern Girl,’ which is the first song that came out and is like the theme song for the band,” he says. “It wasn’t terribly challenging, but I’m most proud of it because it should have been. I have one of those bands where we just do what we do live and it’s like a train on fire.

That’s how I’ve always been; it’s like the last night on Earth. I’m always up against how to capture that in the studio and so often it’s not the answer I think it is. I’ll say ‘Let’s just play it live.’ But the sonic field is what it is and so putting a bunch of people in the studio can feel really cool and exciting, but it’s not going to capture the feeling of [playing] live. If anything, it can sound oddly smaller because you have so many instruments going on. The more you record, the less space you have.

Also, it’s not live. We’re in a studio and we know we’re being recorded. So I went on this long journey and what I ended up with was ‘Modern Girl’ and a lot of the album. The key was to have the band play its ass off and then grab the moments. For example, the horns on ‘Modern Girl’ are later in the recording. But when I heard them, I said ‘Right there. That feels like the electricity of live [playing.]’ I don’t care about anything else. I hear that one thing that gives me that tingle, that frenetic energy of [being] on stage, grab it, start the song with that and almost sample my band. I’m so proud of that one because it cracked the code of how to capture the feeling of my band live.”

Labels: indies versus majors

Bleachers’ first three records were issued by RCA. However, Bleachers was released by indie outfit Dirty Hit. What led to the choice to go indie rather than the well-worn and entrenched major label path? “I spent a little too much time massaging other people’s egos,” he recollects. “It never changed my work, but it was a bit exhausting. I realized that the music business is a funny place, but it’s like any business. You have the great people, if you’re lucky [enough] to find them. Now I’m surrounded by a group that gets me, gets what I do and we’re running towards it together.

“I could write novels on the number of experiences I’ve had with a gatekeeper that in some way I had to satisfy,” he continues. “I was never going to change that feeling. The way I’d appease those people was to make them think [my idea] was theirs too. It’s exhausting. It’s different for everyone, but in my experience, I need a small team that’s ready to go to the moon with me; people that are on my level. Most of the records I make [now] are either me, my band or me and another artist.

Record-making is one of the most delicate things in the world: songwriting, recording, mixing—all of it. You’re building a house of cards that draws upon the deepest emotions, fears and life stories of the people making it. You can be the biggest star in the world, but if someone walks in off of the street and says ‘Wow, that hi-hat sounds like shit,’ everyone in the room is going to crumble. It’s so vulnerable and delicate so it’s easy to dismantle.

The process needs to be kept insular and safe where this group of people are just yes-anding each other to the moon to get where you’re going. I’ve seen and had it done to me where some people have this kind of tough love idea like ‘Oh, that sucks.’ It can be a bit of a male thing, I’ve noticed, to come in like a bull in a chinashop; to lay down the law as to why one thing works and another doesn’t. That’s not how great records are made and it’s how artists get confused. This isn’t to say that that happens more at major or indie labels, but in my experience, any way that you can break your world down to preserve that vision, put the blinders on and do what you’re going to do is a win. For Bleachers, that was a thousand percent an indie label.”

Influences and the importance of hope

Virtually every artist is influenced by other creatives, in small ways or large. The work of '80s film writer and director John Hughes—who gave us The Breakfast Club, Ferris Bueller's Day Off and Weird Science, among others—is what’s resonated in particular with Antonoff. “I don’t know what it is about his films, but they speak to me on every level,” the producer observes.

“He never forgot the hope. The thing I get from Hughes is why I always go back to Springsteen and in a different way to Joni [Mitchell] or OutKast. These artists never give up on that hope. It comes from a core belief that you can’t make art cynically. You can use it as a tool and as a path. But making a record is such a hopeful act that anytime cynicism is introduced, it automatically feels like a tool to get to the hope. My favorite stuff is when artists like John Hughes put that right on display.”

Broadway and Apple TV+

Antonoff wrote the original music for a new version of Romeo and Juliet that will debut on Broadway this fall and produced the soundtrack for the Apple TV+ series The New Look. The show includes covers of World-War-II-era songs from Florence & the Machine, Lana Del Rey and Nick Cave, among others. “One thing that’s nice about having different projects going is that I work on them when they call [to] me,” he explains.

“With The New Look, I made that over the course of about a year. It felt like this inspired island I’d go to. I was working on Bleachers at that time as well as both Taylor and Lana’s records. I’d take two days and orchestrate a song around Nick Cave’s vocal, which was a totally different and beautiful experience. I’ve noticed that’s a way to keep myself sharp: to have widely different things happening.

It was the same with Romeo and Juliet. That sounds like nothing else I’m doing and it’s a different experience where the music was front and center. It invigorates me and I love to push myself in different directions because new parts of me open up. I think people imagine my life to be more scheduled than it is. Usually I create a lot of space for myself to go in different directions, depending on how I feel.”

Creating despite fatigue

Much of Bleachers’ first record, 2014’s Strange Desire, was written by Antonoff while he was on tour with his previous band Fun. “Being on the road is funny because it’s stimulating and you’re filled with so many ideas,” he notes. “But you’re also tired so I always have this emotional wrestling match with myself. I’m exhausted and I want to relax, but I’m also drawn to create. I get so much done on tour from a conceptual level. I ended up writing a lot of lyrics or having multiple ideas of what I want things to be. But then I'll just sketch them out in a hotel room and then get really excited to go into a studio and figure out what I'm doing.”

Sadness, loss and expressing individuality

Songs such as “I Wanna Get Better,” “Everybody Lost Somebody” and perhaps even the entire record Take the Sadness Out of Saturday Night (or, arguably, at least the title) draw from sadness, loss and other such cover-charges that life exacts. “It's something I think about often because it's weird,” the producer says. “Writing songs is a lot like being at a dinner table and telling everyone some deep truth about yourself. And if you're there with 10 people, maybe eight are like, ‘What?’ And then two people are like, ‘Yes, yes! Me too! I also can't sleep unless I imagine myself naked on a cloud’ or whatever it is. So you just write what you write the same way you think what you think.

Then you put it out into the world and that's when you realize a lot about yourself. For example, I remember when Strange Desire was released, hearing it through other people's ears and realizing, ‘Oh, wow. Some of these songs are really sad.’ My life is just my life, so within the context of my sadness, there's a lot of joy and there's everything else. And then just like that dinner table, you find the people who get you and that's your audience. But they tell you a lot about yourself.

It's not horribly different than the experience of therapy: you are what you are and you think what you think. When you start saying it out loud, it hits differently and you realize what it means. In many ways, that’s the core of what a relationship with an audience is. It’s a conversation. Hopefully, the artist is doing that for them. But damn, I'm definitely getting that from them.

“It's the same way that people can tell when a person is being honest,” he goes on to say. “Dishonesty or pandering just doesn’t work and not even in a way where people are conscious of it; not in a way where they’re saying, ‘I don't like that, it doesn't feel honest.’ When something's honest, it can be about anything. It draws people in. It's why I'm remarkably unthreatened by the A.I. conversation.

I’m deeply threatened from a cultural point of view about what could happen, but when it comes to the conversation about writing music and faking things like that, I believe in this sixth sense in people where they feel something and they feel the communication from the artist. No matter how it's dressed up, those are all just ways to get to this place. It's not like five percent of that's good, 80 percent is good. It's a hundred percent or nothing; it's real or it isn't. That’s how I feel and I haven’t been proven wrong yet.”

The introverted performer

Rising comedian Tamale Sepp once said “Don’t presume that just because someone’s a performer that they’re also an extrovert.” Antonoff is a self-described introvert, but, perhaps paradoxically, the stage is where he feels most comfortable and at home. “It’s always been a place where I've been able to completely cut loose and be absolutely transparent in my emotions or where I am with my life,” he observes. “Sometimes I feel it’s easier to speak to a crowd than to one person.

I feel a release. I think that's a trait that a lot of songwriters and performers have. But I'm really introverted in public. I don't mind playing a song with Taylor at Wembley. I'm eager to do it. [But] if I was at a birthday party and someone said ‘Jack, go play a song,’ I think there's a chance I would explode. Quite literally, that's my worst nightmare and I can't explain why I feel that way. I think it's because it's in my soul to connect with people in this big, broad way, which I've become good at, but also may have stunted the part of me that would connect with someone in a very simple way.”

A trove of Grammys

When it comes to his staggering 11-Grammy audio ascendancy, the artist and producer can scarcely grasp the feat himself. “Imagine me being like nine or 10 years old in New Jersey playing guitar and wanting to have a life in music,” he muses. “Then jump-cutting to an interview where someone says that I’ve won 11 Grammys. I'm a kid producing records for my friends and it cuts to that moment in the interview. That's a crazy statement.”

Heading for home

Bleachers will wind up its 2024 tour with a hometown show at N.Y.C.’s fabled Madison Square Garden, less than two miles from the comfort of Electric Lady. Indeed, it’ll be the band’s first time to take the stage at the venerable venue. Once the tour is wrapped, the in-demand producer will then dive deep back into the studio… presumably after a good night’s sleep at home. “I don't think when I have these big things coming up,” Antonoff admits. “I just kind of stay in my zone. I'm working on some music right now, but I won't say what it is. It might sound funny coming from me, but I keep my head down and keep doing what I do.”

With the devotion to his craft, the ever-widening scope of his work and his nearly uncanny ability to create sonic soul-stirrers, it seems inevitable that Antonoff will soon need to add another tier to his Grammy shelf.