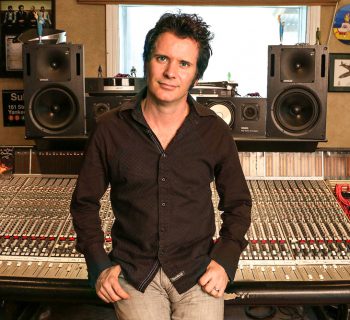

With a roster of artists that includes Katy Perry, Adele, Keith Urban, OneRepublic, Pink, Kelly Clarkson, Dua Lipa, Twenty One Pilots and Deftones, Greg Wells is a remarkably eclectic producer, songwriter and musician. A native of Peterborough, Ontario, Canada, Wells moved to Los Angeles on a scholarship to study with famed jazz composer, piano player and Prince’s string arranger Clare Fischer.

“I’m a scholarship kid,” he says. “My dad (a minister) made $15K a year. I had to pay my own way through college and get every scholarship I could.” Producing and mixing The Greatest Showman Soundtrack––the best selling album of 2018––is a platinum pinnacle for this multi-hyphenate, multi-instrumentalist and multi-faceted creator. In our exclusive interview, Wells reveals the sonic tools, creative philosophies and audio alchemy that he brilliantly distills into pop hits and soundtrack smashes.

Music Connection: Pop music producers historically do not enjoy long shelf lives. You, however, have sustained a career as a producer and a songwriter since the mid-’90s. Does musical diversity keep you from being pigeon-holed?

Greg Wells: As if my discography wasn’t nuts enough––it goes from “Cozy Little Christmas” with Katy Perry to “Suicide Trees” with the death metal artists Otep––both projects of which I’m fiercely proud. I like it that way.

MC: “Cozy Little Christmas” was a highlight of the recent holiday season, a song by Ms. Perry that didn’t drench the listener in clichés, bells and dreck.

GW: I tried to steer us musically to write a real song we’d be proud of in five or 10 years. It’s a classic sort of throwback, hopefully with a modern presentation. It was so much fun making the song; the most fun I’ve had all year working on a project. Ferras Alqaisi, who is one of the best songwriters today, was a co-writer.

MC: In past conversations, you’ve related that Katy is her own woman.

GW: I’m not sure if people know that. They think she’s handed a script like a Britney Spears and told what to sing. It’s the exact opposite. She is telling people like me or Max Martin what to do. She tells her management who will direct her video and she tells her label what the first single will be. She drives it. She’s been like that since the first album.

MC: She had been making the scene in Los Angeles long before her breakthrough. When did you meet her?

GW: I met her when she was 19. She just turned 34. She was this super-brilliant, funny, irreverent, slightly hyper, great singer. She would come here and we would have the most ridiculous time together. I actually had to kick her out of the studio a couple of times because things elevated to such a hyper level––which was partly my fault, too. I’d be trying to mix and she’d be throwing food at me. I had to say, “Look, we can have a food fight in my studio or I can make your record. I think you have to leave.” She left with a smile. Nobody got angry. I really love her. She’s a good egg.

MC: The Greatest Showman Soundtrack that you produced was the biggest record of the year in terms of sales. There is also a Greatest Showman Reimagined.

GW: It came out well over a year ago and I’m still working on music from the movie. I had never worked on a film before. The Reimagined hit Number One on iTunes in the U.S. The soundtrack was the biggest album of 2018––not just in America, but around the world. Nobody saw it coming. I got together a few months back with Michael Gracey, the director. I hadn’t seen him since the premiere of the movie in New York. It was a hard project to get done. Not only had he never made a movie before, but neither had I, and I was in charge of the music.

MC: Was there pushback from the studio?

GW: The studio was sweet and big supporters, but I think they were also having a heart attack at the same time. Fortunately it all worked. We came up against a lot of resistance, him far more than me. He said, “Greg, the one thing we definitely have is that no one will ever be able to say we don’t know what we’re doing on a film.” He held it all together. Hiring me was his idea. His enthusiasm and his vision for the whole thing is the reason the movie exists.

MC: The songs by Benji Pasek and Justin Paul are powerful. “This Is Me” has become an anthem.

GW: When I heard Justin and Benj’s songs they blew me out of the water. They’re just brilliant. How could I say no? I didn’t know it would be a hit and no one else did either. I didn’t care. I knew it would be great. I think they made a modern musical classic. It’s the kind of film people are always going to want to watch. It celebrates the underdogs. There’s an interracial romance in super-racist upper crust society in the 1800’s in New York. There are messages

MC: Have more filmmakers come calling?

GW: I’m working on a new film. I don’t know how much I’m allowed to talk about it. It’s a very hilarious musical comedy with all original music that I’m helping to put together, starring Melissa McCarthy, who is a great singer and one of the funniest people you could ever meet.

MC: Coming off of an ultra-successful project, it’s interesting that you are not following it up with more related projects.

GW: I’m a record maker. I’ve avoided working on movies and television. I love my parents, but their taste in music was pretty terrible, and the way they would listen to music was to put on our crappy stereo, turn up the volume to no more than one or two, and start talking about the weather. Music was just this noise in the background. I think a lot of people treat music that way. I was a young musician who wanted to hear the record and wished we had a better record player. I read a quote from Randy Newman who said, “If I go to a movie premiere one more time when the air conditioning is louder than my songs, I’m going to kill somebody.”

MC: Films must seem exasperatingly complex, with so many moving parts. Music works to serve the picture, whereas in making a record there are less people to please as a record producer.

MC: Films must seem exasperatingly complex, with so many moving parts. Music works to serve the picture, whereas in making a record there are less people to please as a record producer.

GW: I was asked to go onboard because there was no music czar. They had been working for four years. They needed a record producer who could play a lot of instruments and, if they cut out 10 seconds of the scene, would know how to make it sound natural. Michael Gracie is a video director and he really knows music. For movie folks, music is like a foreign language. Mind you, I think music is a foreign language to a lot of record executives in the music business, too.

MC: Crossing genres, we’ve listened to the song you did with Keith Urban, titled ‘My Wave.” It’s country reggae with a rap.

GW: I go to Nashville two or three times a year. I work at a fantastic studio called Addiction Studios. I invite people to come and write with me. Keith Urban was off the road and he came in and did most of a week with me. We wrote with Hillary Lindsay; that one didn’t make the record, but it’s a great song.

Then we wrote with Shy Carter, an African-American kid from Atlanta who has written with Keith on some other songs. He’s a lightning bolt of positively and fun and crazy talented as a writer, a lyricist, singer, song concept guy. He just blew me out of the water. The acoustic guitar part on the record is me, and the brilliant syncopated African-pop sounding thing is Keith. He’s a beast of a musician. Shy was making sounds and rapping, I said, “We have to put that in the sound,” so he’s featured on the song. It’s not Bob Marley and the Wailers, but with more than a tip of the hat to that style. I love reggae music.

MC: Growing up in Canada, did you hear much reggae?

GW: I played in an actual legit reggae band from Kingston, Jamaica one summer when I was 15 years old. They strangely had a connection in my little hometown of Peterborough, Ontario. They came to rehearse for a few weeks for their tour of the Eastern United States and Canada. They had an issue with their percussionist, some passport snafu. My phone rang. It was June, sweltering hot and humid and someone I don’t know says, “There’s a reggae band in town and they need a percussionist. Do you want to do it?” I showed up and they were rehearsing in some church basement––because churches have a lot of space, it’s either free or really affordable.

I got completely immersed in this world I knew nothing about. It was this huge education for me, and quite an imprint on how I have built music since then. Although it probably took several years after the fact for those lessons to sink in and start coming out of the pores of my skin.

MC: We’ve got some gearhead questions. You are using a sonic tool, the Vengeance Sound Avenger synthesizer program. What is it, and how do you use it?

GW: For more modern stuff, the Avenger is just crazy. With synths, most presets are not that helpful, most are bordering on useless. With this thing, every preset when I play it, I think, “I can start a track.” It’s very user-friendly, very musically designed. Whomever is the brains behind it is clearly a great musician and also a record maker because the sounds are like a record; modern, not super-trendy, but also rooted in classic synths. The tones are great and the bass sounds are huge.

MC: What else should we know about?

GW: The Roland Cloud. Those guys have knocked it out of the park. It sounds exactly like my vintage Juno 106 or Jupiter 8. It’s crazy––I’ve A-B’d them with the volume matched and it’s impossible to tell the difference. A lot of virtual synths are lacking low end. Both the Avenger and the Roland Cloud sound like you have a real analog synth plugged in.

MC: You’ve developed your own plug-ins now. What’s new in that realm?

GW: I did a signature series with Waves, and that’s been out for a few years. There’s a little Italian company called Acustica Audio. They make incredible stuff. I fell in love with the first one I bought from them, which is called Cream. I took a photograph with my phone of my computer monitors, put it up on Instagram and said, “This thing sounds amazing.” And it also looks great. The visuals are just gorgeous. I heard from someone from Acustica Audio and they thanked me, and we ended up getting on the phone.

Luca Pretolesi, a great mastering engineer who works out of Las Vegas and is also Italian, has a joint venture with Acustica Studio with his company Studio DMI. He called me and was really happy I liked this other plug-in called the Diamond that he helped develop, which is amazing. And he said, “Look Greg, if you ever want to do a plugin with us you should think about it.”

As he was saying it I was looking at this old 1950’s RCA mono tube compressor that I have that’s like the Holy Grail record making tool. I’ve never heard a plug-in sound like it. And I thought having that on plug-in form would be incredible if we can do it. And if there’s a company that can do it, it’s probably these guys.

MC: How did the process of developing this plug-in work?

GW: Luca drove from Las Vegas and picked up a bunch of my compressors and promised me they’d be in good hands. They flew to Italy and spent the entire summer. They initially got it modeled to where it almost sounded like it. And I thought there was no point in doing it if it didn’t sound like it in every way; unless I can sit in front of my $60 thousand dollar PMC speakers and feel like I can’t tell the difference, then I don’t want to release it. I’d rather pull the plug. I’m so proud of it. I sent it to friends I admire as record makers, and we have presets from Serban Ghenea, who has never done presets for anyone; Mike “Spike” Stent, Joe Chiccarelli, Dave Pensado, Alan Meyerson, who does the Hans Zimmer stuff, David Kalmusky, Mark Rubel, Jason Evigan and busbee––all of these people I really admire as record makers.

MC: You make a great case for working in the digital realm with an analog mind.

GW: Analog has masking qualities. The imperfections of tubes and electricity, transformers, and all the ingredients of the great analog gumbo, in the best pieces of gear are very forgiving to sound. There’s something about the inefficiency of tubes that’s beautiful––the limitations of tape, how it rolls off super high-end and super low-end and changes the sound in the way that analog film changes the look of a photo as opposed digital film. I really like hearing things go through vacuum tubes and big old transformers that suck up way too much electricity. There’s just something gorgeous about it.

MC: Where does the song fit into this equation?

MC: Where does the song fit into this equation?

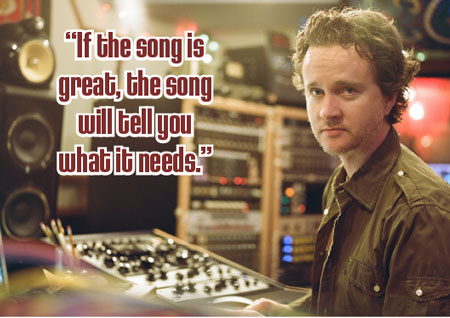

GW: You still need an amazing, jaw-dropping idea, and whether you play it on a virtual synth or a 400-year old Greek bouzouki––whatever it takes to present that idea––is what I feel it should have. And if that means we should record to tape because we want that sound, then we should be able to have it. How do you get it? Is it through actual tape. It could be through printing the mix to a two-track tape machine, which is something I often do.

MC: Having visited your studio, the amount of gear we see is mind-boggling; including three acoustic pianos and a ton of synths, drums, guitars and amps.

GW: I have a big toolbox of stuff, in the same way that a serious photographer has a lot of lenses and camera or a serious chef has a lot of knives and the pots and pans they adore and feel lost without. I’m like that with gear and instruments and microphones. But it doesn’t mean I’m going to use all of them.

If the song is great the song will tell you what it needs. For instance, 99 percent of the time I’m working with a singer. And I learned the hard way that when you have an amazing song and an amazing singer giving you an amazing vocal on an amazing microphone that’s then plugged into an amazing vocal chain, then everything sounds so much better. The drums sound better. It gives everything more buoyancy and life. And it makes everybody involved, from the producer to the artist to the writer to the intern who is getting coffee––it gives everyone more of a career just from the vocal.

MC: You have a classical background and are well trained musically. How does that inform your process?

GW: I spent years taking the bus from my hometown to Toronto an studying classical piano at the Royal Conservatory of Music. I studied orchestral percussion with the percussionist of the Toronto Symphony. I studied pipe organ and music theory and analyzed Bach fugues. It looked like I was going to be a concert pianist at 14 or 15. That’s where I was headed. Then drums were my instrument. I taught myself guitar and bass and learned four-mallet marimba. I was obsessed with every detail of instrument in a rock band and everything to do with percussion. That has given me a toolbox where I can do a lot of different things and maybe it’s a good thing that my taste is very wide ranging.

MC: And you just hit a significant milestone birthday.

GW: I just turned 50. And I am still, somehow, working with the top talent and the biggest names of the music who are, on a good day, calling. It’s never a bad idea to be overly prepared. My songs are on over 120 million albums. I think it’s from a nutty passionate enthusiasm. Whatever talent I do or don’t have, it’s dwarfed by my passion for creating great recorded music. A lot of producers want to write the songs they produce. I’ve been a writer on a lot of songs I’ve produced, but half of my success is for songs I didn’t write. I was happy to be the producer, the musician or the mix engineer because I connected with it.

MC: Last thoughts for MC readers?

GW: Music is a lifetime commitment––it’s the thing that called me. A great chef knows how to make a lot of types of food and that informs the food he makes. A classical conductor plays a number of instruments very well, but when they’re in front of the orchestra they’re not playing anything. That’s how they got the gig––by being experts.

Contact Steve Bailey, steve@hummingbirdmedia.com