The Grateful Dead celebrates its diamond 60th anniversary this year with ENJOYING THE RIDE, a sweeping 60-CD collection that maps an epic cross-country road trip with stops at storied venues where the music, the moment, and the magic of the Grateful Dead reliably converged. Spanning 25 years of legendary live performances, this expansive collection spotlights defining shows from 1969 to 1994 at 20 venues that consistently inspired the band to new heights—Winterland, Frost Amphitheatre, Madison Square Garden, and Hampton Coliseum, among them.

A news announcement from Rhino Records further describes the release.

“With the exception of a few tracks from earlier releases, virtually all of the music onENJOYING THE RIDE is previously unreleased, spanning more than 450 tracks and over 60 hours of music. Of the 20 shows in the collection, 17 are presented in full, with some featuring additional material from the same venue. The remaining three—Fillmore West, Fillmore East, and Boston Music Hall—are curated from multiple performances at each venue, capturing key moments on those legendary stages. ENJOYING THE RIDE was released from Dead.net on May 30th.”

“This 60-CD boxed set is limited to 6,000 individually numbered copies. ALAC and high-res FLAC downloads are also available. For those seeking a concise itinerary, THE MUSIC NEVER STOPPED distills Enjoying The Ride into a shorter route through the band’s diamond anniversary celebration. Featuring at least one song from every venue in the deluxe set, it offers a briefer—but no less illuminating—journey through the music that shaped the Grateful Dead’s live legacy. It’s out from Rhino.com on 3CDs, 6LPs, and digitally.”

“These performances were originally recorded by Owsley ‘Bear’ Stanley, Betty Cantor-Jackson, Kidd Candelario, Dan Healy, and John Cutler. David Glasser and Jeffrey Norman restored and mastered the performances, with select ones using Plangent Processes tape restoration and speed correction for optimal sound quality. The performances featured here include contributions from Jerry Garcia, Ron ‘Pigpen’ McKernan, Bob Weir, Bill Kreutzmann, Phil Lesh, Mickey Hart, Keith Godchaux, Donna Jean Godchaux, Brent Mydland, Tom Constanten, and Vince Welnick.”

In 1976 I conducted and interview with Jerry Garcia at music promoter Bill Graham’s house in Mill Valley, CA. I was not a big Deadhead: I only had a few of the Dead’s albums, and I didn’t trade tapes of their gigs. I had only seen them a handful of times in the early and mid-seventies, but I enjoyed Jerry Garcia’s solo shows, especially a 1973 Ash Grove club date in Los Angeles.

I was fascinated by Garcia. I made no secret of my slender Deadhead resume and Jerry appreciated my honesty. Our conversation was wonderful: wide-ranging and free-flowing, it just jammed, akin to the way he plays music. He was accessible and genuinely interested in me: who I dug, which books I had read, the kind of comics I collected. We talked about the Acid Tests in Los Angeles in winter 1965, and he lit up when I complimented him on his pedal steel playing and his work on Jefferson Airplane’s Surrealistic Pillow. Later, Jerry would repay the compliment by providing liner notes for a release I served as Project Coordinator on, the boxed set Jack Kerouac Collection (Rhino R2 70939, 1990).

The interview began with Bill Graham and me and then Garcia arrived. Carlos Santana was also a part of the interview but this edit reflects only the conversation with Bill, Jerry and me. When Graham left to take some phone calls, Garcia and I just talked casually for an hour. We talked about poetry, the beat scene, Kerouac and the 1969 Woodstock music festival.

Portions of this originally appeared in the August 21, 1976 issue of the now defunct Melody Maker. This captures the rest of my notes; at the time, my budget didn’t allow me to archive my interview recordings so these tapes ended up being reused, so this is all that remains. It has been lightly edited for flow but does a good job of capturing how open and thoughtful an interviewee Garcia was, as well as his easy interaction with Graham.

Harvey Kubernik: Bill, can you remember your first meeting with Jerry?

Bill Graham: I met Jerry in 1965. He was doing the Acid Tests. I thought he and his entire band were from another planet. I was very disturbed at those first parties because—and there’s a lot of differences in opinion—grown-ups as well as kids were testing their metabolism. I was producing theater in San Francisco at that time, where the group was still the Warlocks, doing benefits involving these groups. I got to know him later on.

HK: You both were key figures in Woodstock. Looking back on that now, what do you see?

Jerry Garcia: I really think the scene out here created the possibility for Woodstock to happen. The Monterey International Pop festival—the thing, the activity, music, and people. The set-up was out here.

BG: Before Woodstock, if you had a hit album—700,000 or 800,000 units. Today an album will sell three million units and there won’t be any headlines. How can you retain the quality of the soup when you add water? The beauty of what Jerry is saying is that The Dead, Starship, Santana and others were very instrumental in something that they still retain. Knowing you can sell it, would you give it away? There were free shows put on that didn’t have to be free.

HK: In a business marked by one-hit wonders and trends, how do you account for your longevity?

JG: We’re serious. One of the things you could say about all the bands that came from San Francisco at that period of time was that none of them were very much alike.

BG: There was never a San Francisco sound, or a Boston sound. They may do the same thing to an audience though, which is give them pleasure.

JG: I think each of us has dealt with it in various ways. For me, I know what I’m supposed to do, and I’ll do what I’ll have to do to be able to play. I think almost all the people I’ve known around this area, involved around the music scene, have been faithful to that thing.

BG: Jerry just hit a key. There is something that they’re always had in common from the beginning, something hardly spoken about in the media after all these years. The San Francisco bands, starting with the Dead, always went to the gigs with the intention of putting it out there. It was the lack of professionalism at the beginning that made that possible. It wasn’t that the contract said 45 minutes and “that’s what we’ve got to play.” They were the first one who asked to play longer. They wanted to extend the relationship between the audience and themselves. And that prevails to this day. You can’t get them to play shorter sets. Carlos always wanted to play longer which is very different from the professional attitude that you get.

BG: One of the reasons for that—and Jerry won’t say it—is you get a man like this who can make all kinds of money across the country. The Grateful Dead just came off the road, and he has a desire to play, and he takes his band and plays a club that holds 400 people! When you go out, you want to make music and you want to make a living. There are times when I really think the Grateful Dead are demented—insane. They could have made ten times as much money.

HK: Do you feel parental about some groups or individuals you’ve got close to over the years, Bill?

BG: Words are thrown around—brother, sister, parental. All I know, some ten years ago they think I’m a very good businessman. I think I know how to deal with people, but not a very good businessman. I think I have some idea about music and what the streets are all about, and about what downtown is all about. I was a New York energy freak to some extent, and I still am. But I found out every mile didn’t have to be four minutes. I didn’t have to catch that plane. If you would have told me ten years ago that I would someday live under trees, I would tell you you’re crazy. I learned this from the Bay Area, from the feeling in the Bay Area. Jimi Hendrix once came late for a show; I’m pacing in front of the Fillmore. And he gets out of the cab, and I’m yelling at him, and he looked at me and said, “There was this great movie on in the motel.” Little by little, it took me four or five years to learn this. I finally realized that after the gig I could do the yelling. In the long run it’s the public that has to get the good energy from them. I really sincerely feel this, is that the reason the relationship lasted over the years, is that those of us who live in the Bay Area and lasted over the years have always had the same goal. We want to turn people on and we want them to have a good time.

HK: Both of you were cultural heroes of the Bay area scene. Was there any added pressure being a mouthpiece for the community?

BG: Everybody knows who they are. No matter what you read about you in the paper, you know who you are. You don’t get any special breaks at the gas station. You can either be sucked in by that stuff, in which case it just eats you, or else just realize there’s a difference between what you read and who you are.

HK: Didn’t you ever feel you represented something special to the honest music community?

JG: I always did. I think that the world has changed. I think the United States has changed very visibly in the last ten years. A lot of it had to do with what happened in San Francisco. I can’t say how or why, but I also think it’s affected everything?

HK: Like how?

JG: Just all the interest in things like ecology. All the interest in the sense of personal freedom as expressed by all kinds of movements. All these things were designed to free the human. Social overtones. All that stuff. The communal spirit.

BG: That’s the dilemma a musician has. A musician may think he played a shit set, and the audience out there is going crazy.

HK: Rock and roll has moved into the big arenas. Was that the logical extension from the Fillmore and even the ballroom circuit?

BG: You can’t get any bigger, Man, has reached the largest securable facility. The reason Woodstocks don’t work is that you can’t put up walls. You can put cement around a stadium. Okay, if you want a couple of hundred thousand people, there are no facilities that large except for cocker. It’s been proven that if you can put up a fence to contain 450,000 people, how do you stop the other 200,000?

HK: Could you predict the vastness of the present concert situation?

BG: Yes, and I must be honest at the same time and cop to the fact that a lot of the things I was putting down predicting what would happen, did happen, and I joined the ranks. We may have created the ranks and everybody joined them. Basically, what it amounts to is supply and demand. The artist’s theory is that “my life is so busy now,” and he would like to be with the luxuries life has afforded him. If the Dead could spend one night in San Francisco playing a big gig instead of three smaller shows, the next two nights are theirs to be in their home or with their lady. That’s the key; it’s not that they want to play less. In the summer of 1973 or ’74, we took Crosby, Stills Nash and Young, who came to us and said, “we want to play a lot of indoors and outdoors dates,” We did a 31 city tour. Seventeen of those dates were in ballparks. That was the beginning. The logistics could work.

HK: Have you always liked playing live? You strike me as a workaholic.

JG: I like the live experience. That’s where it counts. That’s when music is real. It’s real in that situation. That’s the situation that I feel I have the greatest sense of personal responsibility about. I don’t mind putting out a bad record, but I really hate a bad concert. That really is depressing.

HK: You get into other musical avenues with solo projects away from the Grateful Dead. Has there ever been any conflict or compromise in doing a tune for the Dead or keeping it for future solo endeavors?

JG: It’s not judgmental. You can’t deal with it in a yes/no kind of fashion. For example, my band is a band that could best be described as consonance and harmony. Conceptually, everybody in the band thinks pretty similarly. In the Grateful dead it’s a situation in which almost no two people have the same conception musically; which makes it harder. Nobody gets their way. However, what we all respect about that situation is that there is a potential of a larger central viewpoint which none of us, individually, are capable of perceiving, but which we all add to because of the diversity and the conflict.

HK: Did you ever think ten years ago that the Grateful Dead would get beyond the ballroom circuit and that rock and roll would be presented in baseball stadiums?

JG: When the Acid Tests were happening, I personally felt “In three months from now the whole world will be involved in this.’ So, as far as I’m concerned, it’s been slow and disappointing. Why isn’t this paradise already? [Laughs.] My personal feeling has been one of waiting around.

HK: Being an elder statesman in rock and roll, how long do you feel you can continue the hectic pace and touring?

JG: I’ve learned that it requires a certain discipline for me personally. And I know I’ll approach it in a certain way. I’ll definitely burn out, and I wouldn’t survive a tour, for example. For me, it’s a matter of surviving. This is the set of givens. You’re gonna be in airports, motels, exposed to any number of strange drugs, strange experiences, intensity of this sort, and so forth. Within that framework how do you stay even? What you do is learn so it becomes a thing of pace, vitamin C, protein. You try and stay alive. That’s a fundamental problem. I’m just the sort of person who deals with things on that level. Once I know things what I have to cope with, it’s just a matter of adjustment. I just hate personal failure, being on stage and going through the changes and playing bad because I’m either not well, tired, too stoned, whatever. To me it’s an aversion therapy thing. It’s the reason I’ve been able to survive.

HK: Jerry, do you have high and low points looking back over the last ten years?

JG: Well, I can get into that real easy. The worst for us and for me personally was Woodstock: the ultimate calamity. First of all, we were really stupid in the way we dealt with it. It was raining and we went on just after it got dark. There was maximum confusion going on, sound logistics. Really weird. Plus, I was high, of course. And I went on stage in a state of confusion. Huge crowds of people over the stage. The stage had sheet metal and stuff on it, it’s wet, and I’m getting incredible shocks from my guitar. Pretty soon I started hallucinating ball of electricity rolling across the stage jumping off my guitar. Meanwhile, all the little citizen band radios and walkie talkies and things with the amplifiers so there’s weird voices coming out of the amplifiers. It’s dark, and you don’t see any audience, but you know there’s 400,000 people out there. Then somebody leans over across the stage, since everyone is ganged up, and says the stage is about to collapse. I’m standing there in the middle of this trying to play music. Then they turn on the lights, and the lights are a mile away. Monster super troopers. Totally blinding, and you can’t see anything at all. Here’s this energy and everything is horribly out of tune, ’cause it’s all wet, damp and humid. It was just a disaster. It was humbling. [Laughs].

(Harvey Kubernik is the author of 20 books, including 2009’s Canyon Of Dreams: The Magic And The Music Of Laurel Canyon, 2014’s Turn Up The Radio! Rock, Pop and Roll In Los Angeles 1956-1972, 2015's Every Body Knows: Leonard Cohen, 2016's Heart of Gold Neil Young and 2017's 1967: A Complete Rock Music History of the Summer of Love. Sterling/Barnes and Noble in 2018 published Harvey and Kenneth Kubernik’s The Story Of The Band: From Big Pink To The Last Waltz. In2021 the duo wrote Jimi Hendrix: Voodoo Child for Sterling/Barnes and Noble. Otherworld Cottage Industries in 2020 published Harvey’s Docs That Rock, Music That Matters. His Screen Gems: (Pop Music Documentaries and Rock ‘n’ Roll Television Moments) is scheduledfor 2025 publication.Harvey wrote the liner notes to CD re-releases of Carole King’s Tapestry, The Essential Carole King, Allen Ginsberg’s Kaddish, Elvis Presley The ’68 Comeback Special, The Ramones’ End of the Century and Big Brother & the Holding Company Captured Live at The Monterey International Pop Festival. During 2006 Kubernik spoke at the special hearings by The Library of Congress in Hollywood, California, discussing archiving practices and audiotape preservation. In 2017 he appeared at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland, Ohio, in their Distinguished Speakers Series. Harvey in 2023 was at The Grammy Museum in Los Angeles discussing The Band’s documentary The Last Waltz).

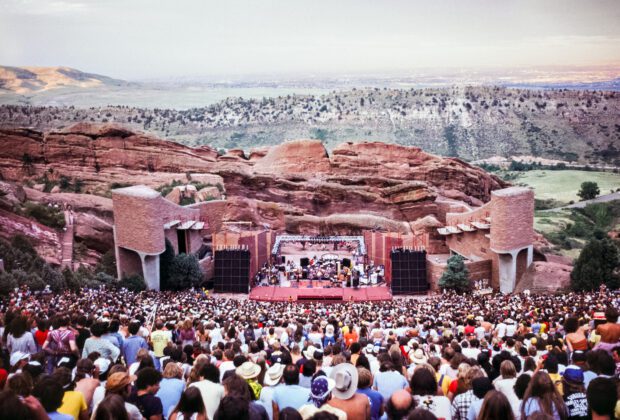

Photo by Rhino Records