SyncLove.com is a new channel from sync licensing and music discovery platform SyncFloor, which invites production professionals to dive into their favorite moments in films and share the scenes that changed the way they think about music for picture. With in-depth interviews, SyncLove offers good reads and intriguing insights about what works in sync, and how powerful the combination of music and picture can be.

--

The SyncLove guest contributor for this post is Kyle Seago. Kyle is a documentary filmmaker and film festival cofounder drawn to stories centered around artists and the human condition. His career started in Seattle working on indie feature films, then took him to LA where he emerged as a producer in reality television. He eventually landed back in Seattle developing and directing documentary projects for an array of brands, foundation partners and media outlets. Music and the musicians often drive his work, leading to and including collaborations with Major Lazer, ODESZA, Shabazz Palaces, Chimurenga Renaissance and Flosstradamus.

Kyle has chosen The Last Black Man in San Francisco as the highlighted film and soundtrack for discussion. To him, the film blurs the boundaries between documentary and narrative film and the music weaves an emotional storyline almost as important as the visuals it supports. Haunting yet inspirational, the score roots the characters in the nostalgia of their ancestors but points forward to a future as bright as we make it.

Movies don't exist in a bubble. They are the combination of people’s experience, stories, actions and feelings. As a filmmaker, when you set out to create a film rooted in fiction, you are manifesting all of those things into a frame with actors, lighting, locations, costumes, written dialogue, and - often at the heart of all of that - music. The soundtrack to a film is the heartbeat that drives the emotional connection; it tells the audience how to feel and where to look, and to me, is what turns a two-dimensional viewing experience into an all-encompassing connection with the characters on the screen. Although it is often one of the last pieces that fills in the complex puzzle of a film, the musical elements make the puzzle complete and help the images feel more cohesive and imaginative.

In documentary film, when the world on screen is real and the characters are real, the story’s power often teeters on the realization that what you’re watching happened and exists in our world. It could potentially happen to any of us. The human condition is the backbone of many documentary films; examinations of what happened and why, who was involved and what was the lasting effect. As a documentary director, when storytelling options are limited by what actually happened and the access you have to those who can tell you about it, music becomes even more vital. It also becomes more complicated because you have to be sure that your musical pairings match the emotional state of the real people involved in the film (or at least of the story they are telling).

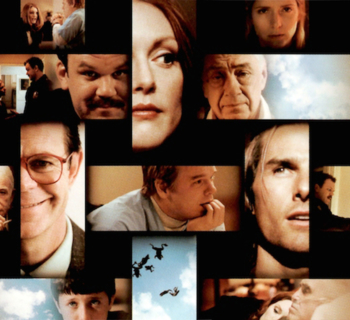

The film The Last Black Man in San Francisco straddles the worlds of fictional and documentary storytelling. Based upon the true story of Jimmie Fails (who plays himself in the film), the central theme of the film is an exploration of forced displacement - also known as “gentrification” - and its effect on generations of black families in San Francisco. Arguably, the main character of the film is a centuries old Victorian home that Jimmie is trying to protect and maintain for his and the next generations of his family.

Emilie Mosseri wrote the music for the film and the haunting, driving orchestral strings and horns bounce off the hollow walls of Jimmie’s neighborhood as he ventures to preserve his family’s past and create a prosperous future. This film is driven by the balance between what is known and unknown. Jimmie knows the damage that has been done to his family by forced displacement, but does not know the best way forward. The newcomers to the neighborhood know that their presence is harmful and widening a deep racial divide, but choose to ignore that fact. The music score straddles those unknowns with delicate woodwinds that motivate Jimmy to pursue what he believes is right in the face of all these unknowns: the preservation of his family home. The building repetitive horns in the track “Black Alice in Wonderland” remind us that for many people who have been forcefully displaced, the boiling point hit a long time ago and the last stage of grief has been reached. What Emile manages to do with this elegant score is inject wistful optimism into a story that could easily dwell in the sadness of a realized situation. Instead of dwelling on the plight of Jimmie, the film instead looks to his heart, his drive, and his ability to navigate the streets he once knew and the new inhabitants he doesn’t know at all. There’s an optimism to every track, even if that optimism is rooted in acceptance.

In a soundtrack featuring all new compositions that elegantly flow throughout this visually stunning film, the lone music track of familiar recognizance is a rendition of “If You’re Going to San Francisco” originally by Scott McKenzie. The song is performed in the film by a black street performer, striking symbolism for a traditionally black neighborhood in San Francisco being flipped into a gentrified real estate hotbed, leaving longtime residents nostalgic for a past fading from memory like the paint on a dilapidated wall. The street performer is Michael Marshall, best known as a Bay Area legend who provided the hook for the legendary Luniz song “I Got Five on It”. While the original 1967 version of “San Francisco" was deemed "the unofficial anthem of the counterculture movement of the 1960s" this new take on the song feels like a soft cry lamenting the influx of people that the original song invited to the neighborhood.

The street performer's voice is mournfully reflective; hostile takeovers of long-held family properties are an inevitability. The San Francisco we once knew as a peaceful safe haven is safe no longer. It now has a high barrier of entry that is designed to keep its original inhabitants out. The film version of the song hooks you with Daniel Herskedal's nostalgic low tuba and sparse instrumentation, and then the haunting voice of Michael Marshall reminds us all that our existence is beautiful yet fragile. While the 1960s innocence of a flower tucked behind an ear was a futile attempt to prevent war in far off lands, the war on black culture and property in modern San Francisco wages on while newcomers stroll in adorned with floral shirts and iced lattes. When the street performer finishes his song, Jimmy Fails, the film's main character, asks the performer “what else you got?” in a desperate attempt to turn the attention away from what has been lost and towards what is yet to be found.

Personally, I have never been so emotionally struck by score as I was with this one. It catches you off guard, both because many of the sounds are familiar - like those you might hear in a traditional narrative film. But the meaning behind the instruments takes on an entirely different tone when placed - both physically and emotionally - against the background of systemic displacement. The delicacy with which Mosseri adds power and aspiration to a film that could swell in sadness left me in awe. I won’t soon forget the visual poetry of a street performer belting the iconic chorus of a 1967 anti-war anthem as cranes swing overhead and for sale signs bloom down cobblestone streets.

I greatly respect the way Mosseri and the director were able to dance between melancholy and motivation in The Last Black Man in San Francisco. I think many documentary films fall into the trap of having to choose between those two emotions and the more that we can intertwine them, the better our storytelling can be. I’ve taken inspiration from that on a couple of recent projects that are personal profiles of people I know.

I’ve been working on developing a living history documentary project centered around the idea that everyone deserves to tell their story before they die, even if only for the historical record on that time and place. I’m going to continue developing that project and hopefully secure funding and develop a structure through which I can make that a full-time project. Outside of that, I’ve been still working on a foundation-funded documentary series for PBS centered around Alaskan pioneers, a few pieces for nonprofit partners, and a project exploring financial literacy for young adults.