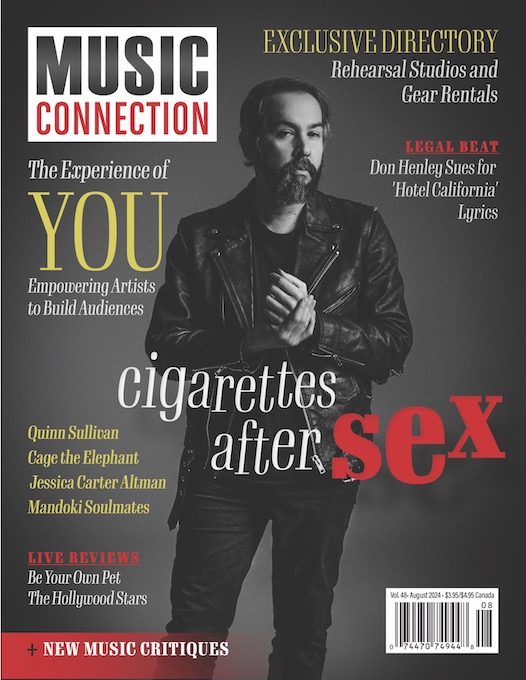

Formed in El Paso, TX, in 2008 by Greg Gonzalez, indie dream pop trio Cigarettes After Sex (CAS) has crafted its unique sound, built its audience and harvested the fruits of its career. CAS’s first project – the 2012 EP I—was recorded in a four-story stairway of a building on the University of Texas at El Paso campus.

A number of singles followed, some of which were released on the band’s label Spanish Prayers, and YouTube views soon spiked. Emboldened by its initial success, CAS hit the road and crossed the world. Writer, vocalist and producer Gonzalez, drummer Jacob Tomsky and bassist Randall Miller soon relocated to Brooklyn and landed a deal with neighborhood label Partisan Records, which began, as many do, as a scrappy indie startup.

The band has since flourished and the world tour for the recent X’s (which dropped in July) kicks off at the end of August. It will take in such storied venues as Madison Square Garden and the O2 Arena, both of which are sold out.

It’s an ambitious undertaking for an indie band to tour the world merely on the strength of an EP and a cluster of viral songs. It feels reminiscent of a 15-year-old who runs off to join the circus only to return at the end of the season as the ringmaster. But as in many adventures, fortune favors the bold.

“It’s funny,” Gonzalez recollects of the time, “because pretty much we had six songs to take on the road. We’d already recorded and rehearsed a lot of the stuff for our first LP [Cigarettes After Sex] so we previewed several of the new songs. ‘Apocalypse’ is our biggest single now [to date, the 2017 song has earned nearly a quarter of a billion YouTube streams] even though it wasn’t out then but we played it at every show."

"It was great because it wasn’t that scary. We felt that we were in good hands with our agents and management. There was an element of it being a new experience, of course. But in all honesty I’d been waiting for that opportunity my entire life so I was elated. The shows back then were incredible because they were smaller, all sold out immediately and the fans went crazy.”

With this level of self-made success, it would seem that a deal with a label would be unnecessary or perhaps even border on needless. Having already built a fan base and pulled off a successful overseas tour, what more could a label do for a band? Moreover, why cut one in on the profits? But the choice to sign with Partisan Records—an indie label launched in a Brooklyn apartment and now with a presence in London, Berlin and Los Angeles—was still made.

“You grow up and think that you’re supposed to get signed to a record deal,” Gonzalez observes. “That’s the way that it’s painted to you; it’s the way that it happens in movies. So I thought that was the way to do it and it kind of still is to me. There are so many aspects to putting out a record and it’s already enough for me to try to run everything on my own; to keep the image quality up to snuff. We did well independently like when we went viral on YouTube. But we needed someone who could work for the music and get it in all of the right places. Partisan has been great about that.

“Our first record [the EP I] was self-released on our label Spanish Prayers, which we still have,” the frontman continues. “We released I and some of our singles on it. But we have nowhere near the resources that Partisan does—the know-how and expertise."

"They’ve been generous enough to not want to mess with our formula or get in the way of the decision-making. Early on we talked with a million labels, many of which I love and still do. But they wanted to change a lot about us so we knew we wouldn’t go with them because we didn’t want to homogenize everything. I’m sure that’s worked with other bands they’ve signed. But for us, I wanted to be away from all of that and in our own little corner.”

It’s not unknown for there to be gaps between record releases, sometimes substantial. Bands come off of the road weary and with perhaps only a few new songs or even just ideas in their pockets. CAS’s last record Cry dropped in October of 2019, which represents nearly five years between its release and X’s. To an outsider, this might seem like a long time. But as with most complex things, there were reasons, as Gonzalez explains.

“It took such a long time because we were trying out ideas forever at the Bootleg Theater in Los Angeles. We finally recorded the main sessions in this little room of the house where I was living near the Hollywood Bowl. So this is like an L.A. record to me and it’s the first one I’ve done where I was living. For some reason I have to do vocals at home and we’ll record [the music] somewhere else. So the extent of my home studio is just a place to record vocals. That’s a nice little ritual.

“I knew I wanted to do something different after Cry,” he continues. “I wanted to return to our first record. What’s that thing about ‘Your first record can take your entire life to make?’ Cry was a short chapter of whatever I was going through at that time. The first LP was longer; it includes different relationships. I thought that X’s should feel more like that: a longer story. I knew when it was time to say ‘OK, this is the record.’ [A relationship] was kind of falling apart and it felt like the best time to conclude the writing and commit to what the story was. I knew it would take more time and I wanted it to represent a bigger period of [my] life.”

The ways in which artists prefer to create often seem as varied as the work that they produce. Gonzalez finds that he’s most prolific when he sticks to a disciplined schedule. “I write compulsively and usually do my best work if I write daily,” he notes.

“But I only do it if I want to; when I feel like doing it and most of the time I do. For the past five months I haven’t wanted to write anything because this record felt like it was a lot to put out, emotionally, and I was drained. I write alone so there’s nothing in the way; nothing to distract me. I can completely let go and it’ll be pure feeling and I’m not aware of anyone else in the room."

"When I record vocals it also feels like I need to be by myself since it’s so intimate. I’m still quite shy to sing in front of anybody, especially when I first do a song because it’s really raw and emotional at that point.”

Both producers and recording engineers can play a significant role in how a record is crafted; the way it’s shaped and the way it sounds. In the case of CAS, Gonzalez has always taken the lead on both fronts. “I tend to engineer on my own,” he says.

“The way that I record is to put up a bunch of [Shure] SM58s [mics] and we play everything live. It’s very straightforward, like we’re rehearsing or playing a show. I knew I could get a great sound if I made it as simple as possible. Production to me meant it was like we were back at [legendary Memphis recording space] Sun Studio: I just put up some mics. It’s very old-fashioned. For me [our sound] is supposed to harken back to an era of music you don’t hear as much anymore.”

Making a record can be both taxing and testing under the best of circumstances. Certainly there’s much to be said for being close, geographically, to your bandmates. That was the case with earlier CAS records. But not so while recording X’s. “It was harder because we were all in different places,” Gonzalez recollects.

“It was nice when me, Jacob and Randall all lived in the same city because there was a lot of back and forth. Now that we’re not—Jacob’s in New York and Randall was traveling at the time—it’s harder to do; to keep a rhythm or a groove going. This is the first record we’ve done like that and it was a challenge. Our first LP was recorded in a small Brooklyn rehearsal space in the dead of winter and our second we did in Majorca, Spain.”

For a time, the band made N.Y.C. its home. The vitality and density of that humble hamlet at the center of the universe cannot be denied and many artists flock to it for these and other reasons. But recently Gonzalez settled in Los Angeles, at least for the time being.

“New York is my favorite city in the world,” he shares. “I came to Los Angeles because New York is pure electricity and creativity. But it also sucks me in. It’s a lot to deal with. I find that when I’m on tour, that fills the New York energy of constant thrills. I need something to return to that’s away from that, which is what L.A. is for me.”

Among the things that are easy to overlook when people think of what it means to be a successful musician—a rock star, if you will— are the countless experiences that are hard to grasp fully unless lived directly. For Gonzalez, one of his most prized memories has been receiving praise from artists that he admires. “It’s that magical moment when an artist you love comes back and is obsessed with your music,” he asserts.

“That’s happened a few times. The greatest was Françoise Hardy, who just passed away. She was my favorite singer; I used to wear a Françoise Hardy T-shirt. We finally got to meet her a few weeks ago. She was like a teenaged fan and even wrote an article about us. That was pure bliss to see someone you admire and took so much influence from to come back and say that you’re amazing. Then there was David Lynch. The Julee Cruise record Floating into the Night that he produced is one of my favorites. He’s talked about us quite a bit and said that ‘Sweet’ was pretty much a perfect song. I’m also a huge Elton John fan and he’s played us on his radio show [Rocket Hour].”

It’s tempting to presume that artists are calm, confident and self-assured when he, she or they are about to release a record. Surely there are no doubts that it’s a masterpiece and the world will embrace it. But artists, of course, can suffer from the same fears, anxieties and trepidations as do non-rock-star stock. “I do get a bit nervous when a record’s about to drop,” Gonzalez admits.

“Writing is cathartic; it’s pure therapy. The whole journey of it is that you write the songs and that’s usually the most fulfilling part: when I finish one and it’s on the page. It’s a euphoric moment. The recording is also magical but singing is usually the hardest part. That’s where I’ll be the most emotional. Usually if I’m on the right track I have to cry a lot. It means that I’ve hit a nerve or gotten to the core of something that’s really moving."

"Often times it’s the things that I wasn’t even aware of; I didn’t realize that I felt a certain way about a person. Even when I was making records in El Paso I still had to release them in some capacity. Then maybe a few friends heard them. It felt validating that it was out in the world. That meant that it was finished; I’d completed the journey; I’d reached the destination."

"The nerves I have are that I’m about to reach that destination and then I can let go of these feelings or process them, learn from them and move on. That’s all a bonus. If someone else likes it, it feels amazing to share music with people, especially if it helps them. For X’s, it’s been a five-year journey.”

Artists issue records in a number of formats, of course: vinyl, CD, digitally, etc. In recent years a cluster of them—Taylor Swift, Twenty One Pilots and Harry Styles all come to mind—have included cassettes among their offerings. It almost feels like what artists used to say about vinyl decades ago is now being said and felt about cassettes: they remind them of records they loved in their youth. CAS is in that subset of artists that drop new releases in several formats including on cassette, which could now be deemed vintage.

“I grew up with them,” Gonzalez recalls. “A lot of those early ones are very dear to me. I wasn’t ever a big vinyl listener. Growing up, it was cassettes. I had [Michael Jackson’s] Thriller, Queen’s Greatest Hits and Classic Queen on tape. They have their own charm and may even be my favorite physical copies of our records. There are a lot of [pressing plants] that still make them.”

Beyond interest in a band’s latest project, perhaps the most telling question that can be asked is what lies in its future. Gonzalez has an interesting conception of bands’ career paths. He feels that each record is similar to an individual chapter of a book and when the band breaks up, its catalog—the entire body of its work—is like the completed book. “I’m trying to model Cigarettes After Sex upon other heroes,” he observes.

“That’s always worked out best for me. I’m thinking that maybe we should only do five or six records and then lock the door and throw away the key. I love when bands become like a locked door. There’s some power to that. The Beatles had it, so did the Smiths, Cocteau Twins, R.E.M., Talking Heads. The idea that they’ve said all that they can say as a band and they’ll move on to other things makes sense to me.”

Cigarettes After Sex’s X’s is out now. The world tour kicks off on August 31 in lively and leafy Montreal, and will reach as far as East Asia and South Africa. Not bad for teenagers who ran off to join the circus and returned as its ringmasters.

The three most important lessons that Gonzalez has learned about being a success as an artist are:

1. You have to be resolute and persistent.

2. You want [your] music to be felt. It’s more about feeling than thinking. Keep that in mind when you write. Don’t try to copy something that’s selling. Never make a decision based on money. It can destroy the spirit of what music should be.

3. The more I confront emotions in music, the more rewarding it is for me and it feels like it is for the listener, too. When you’re honest, people can feel that.

For more, contact kip@tellallyourfriendspr.com