2020 marks 100 years since Ravindra Shankar Chowdhury’s birthday on April 7, 1920 in Varanasi (also known as Benares) United Province.

Ravi Shankar was one of the most influential artists in Indian history, a musician who introduced countless western audiences to his country’s native sounds, and proved the versatility of his sitar instrument, the long-necked stringed instrument from the lute family, in his collaborations with everyone from rock legends to symphony orchestras.

Family, friends and additional guests will acknowledge and celebrate Shankar through a series of concerts called Ravi Shankar Centennial Concerts.

Among the performers are daughters Norah Jones and Anoushka Shakar, Philip Glass, Dhani Harrison, and Nitin Swwhney with an orchestra of the late musician’s “foremost disciples.”

The special guests will perform at selected concerts in San Diego, Los Angeles, Chicago, New York, London and New Delhi.

Norah Jones and Anoushka Shankar will perform at Southbank Centre (April 7) and Walt Disney Concert Hall (May 19); Anoushka also performs at San Diego Civic Theatre (May 16), Chicago Symphony Orchestra (May 22), and Carnegie Hall (May 29). Philip Glass to perform at Carnegie Hall (May 29), and Dhani Harrison will perform at San Diego Civic Theatre (May 6) and Walt Disney Concert Hall (May 19th).

The Ravi Shankar Centennial Concerts includes the following disciples: Vishwa Mohan Bhatt (Mohan veena), Tarun Bhattacharya (santoor), Kartik Seshadri (sitar, only U.S.A.), Partho Sarothy (sarod), Shubhendra Rao (sitar), Gaurav Mazumdar (sitar), Barry Phillips (cello), Sanjeev Shankar (shehnai), Ashwani Shankar (shehnai), Ravichandra Kulur (flute), Bickram Ghosh (tabla), Tanmoy Bose (tabla), Pratik Shrivastava (sarod), Pirashanna Thevarajah (mridangam, ghatam, morsing), B.C. Manjunath (mridangam), Kenji Ota (tanpura), and Nick Able (tanpura).To celebrate the centennial of Ravi Shankar, author Oliver Craske will release a biography, Indian Sun: The Life and Music of Ravi Shankar (Faber Books, April 2020).

Additional centenary releases will be announced in 2020. Last century Shankar published his own autobiography, Raga Mala. Shankar’s first book, My Music, My Life was the subject of the film Raga, which documented his musical roots and his role in America.

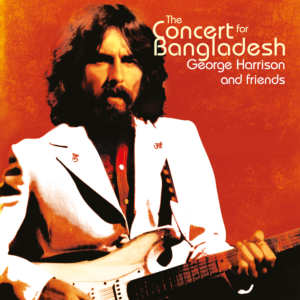

Next year will be the 50th anniversary of The Concert for Bangladesh, a pair of benefit shows organized by Shankar and George Harrison in New York City at Madison Square Garden that raised awareness and fund relief for East Pakistan refugees, after the Bangladesh Liberation War-related genocide.

It was in Los Angeles earlier that summer of ’71 when Harrison was alerted to the scale of suffering his friend and sitar teacher Shankar was feeling about the struggle for independence from the ten million East Pakistanis refugees who fled over the border from West Pakistan to neighboring India to escape mass starvation, hunger, and death.

Nearly three million people were killed. The crisis and dilemma was deepened when the Bhola cyclone and floods in 1970 devastated the region. At that period only small funds and help were made available from foreign governments.

Harrison, Ringo Starr, Bob Dylan, Leon Russell, Billy Preston, Eric Clapton, Jim Keltner, Jesse Ed Davis, Klaus Voorman, Badfinger, Claudia Linnear, Ravi Shankar, Ali Akbar Khan, Kamala Chakravarty, and Ustad Alla Rakha were among other recording artists who donated their services.

At age 10 Shankar accompanied his elder brother, Uday Shankar, and his dance troupe to Paris where he attended school and absorbed the music traditions of the West. After meeting guru and multi-instrumentalist Ustad Allauddin Khan at a music conference in 1934, Shankar moved to Maihar, India, in 1938 where he studied sitar under Khan.

In 1946 Shankar went on to become music director of the New Delhi radio station All-India Radio, a position he held from 1948 until 1956. During his time at All-India Radio, Shankar composed pieces for orchestra, mixing sitar and other Indian instruments with classical Western instrumentation and performed with India’s most noted percussionists. He composed film scores for Indian director Satyajit Ray’s 1955-59 Apu trilogy.

Shankar’s debut U.S. album release was Ravi Shankar Plays Three Classical Three Ragas in 1956. He continued to provide well-received soundtracks in both East and West, including Kabuliwala in 1956, for which he was named Best Film Music Director at the 1957 Berlin Film Festival.

In 1966, Ravi played the first sitar-violin duet with Yheudi Menuhin at the Bath Festival and, the following year, he reprised the collaboration at the United Nations as a centerpiece of the Human Rights Day celebrations.

Shankar's relationship with the Beatles began in the '60s, when he began giving sitar lessons to George Harrison, who later played the instrument on the Beatles' "Norwegian Wood."

Ravi’s groundbreaking appearance at the June 1967 Monterey International was witnessed by songwriter and musician Al Kooper, then doing a stint as assistant stage manager for the epochal gathering

“I was sitting in the audience with another artist. And I’m getting an education because I don’t know much about it. Don’t know much about Ravi just picked up on him through the Beatles like everybody else. Watching the musicianship between Alla Rakha and Ravi Shankar killed me. I thought that was amazing when they were trading passages,” observed Kooper.

“Monterey reached its climax for me in the early afternoon and there was a light drizzle and we went to hear Ravi Shankar,” added actress Peggy Lipton. “I remember I left my body. That was it for me. It was beautiful, peaceful and chilled everybody out. Ravi transported me and he transported everybody. We were all taken there. It was like we were put on a spaceship and driven to another planet.”

Shankar contributed to Ralph Nelson’s Oscar-winning Charly in 1968 and spotlighted in the acclaimed D.A. Pennebaker-directed ’68 documentary Monterey Pop.

“I knew when I saw Ravi Shankar we would have to end with that,” Oscar-winning filmmaker Pennebaker happily confessed in a 2004 interview we conducted.

“I remember sitting down at Max’s Kansas City and I wrote out a little thing on the back of a menu of what I thought the order of the music would be. And you know, it was very close to what ended up being. It had tobuild from Canned Heat to Simon & Garfunkel to whatever it was, it had to be a history of popular music in some weird way that I didn’t ever have to explain to anybody ‘cause I had music as a narration for the whole film so that just covered me.”

In August 1969, Shankar performed at Woodstock. He then received an Academy Award nomination for his music in Richard Attenborough’s Gandhi. Shankar recorded with conductors Andre Previn and Zubin Mehta.

During 1971, Shankar partnered with Harrison to produce the Concert for Bangladesh, which took place at Madison Square Garden in 1972 and raised funds for UNICEF. The live recording of the concert ultimately won the Grammy for Album of The Year. Shankar received five Grammy Awards throughout his career and a Recording Academy Lifetime Achievement Award.

Together with composer Philip Glass and several other composers, Shankar co-composed "Orion," which opened the 2004 Cultural Olympiad in Greece.

Shankar passed away on Dec. 11, 2012, in San Diego, Calif., at the age of 92. On December 20th a memorial was held for Shankar at Self-Realization Fellowship in Encinitas, Ca.

The windmill chapel at the Lake Shrine in Pacific Palisades California carries on Paramahansa Yogananda’s spiritual and humanitarian Self Realization Fellowship work and legacy and hosted George Harrison's funeral service in 2001.

It was also in 1966 that Shankar first met George Harrison. Harrison had first heard the sitar on the set of the Beatles’ movie Help! In September 1966, Harrison traveled to Bombay and became one of Shankar’s students.

Later that same year, he would record with the instrument on John Lennon’s “Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown).” Subsequently, Harrison integrated the sitar into his own composition “Love You To” from The Beatles’ Revolver album, as well as fusing sitar and Indian influences on his selection “Within You Without You,” on the influential Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band album and also on “The Inner Light,” the obscure B-side to the “Lady Madonna” single.

In 1997 I interviewed both George Harrison and Ravi Shankar. Portions were published in HITS magazine.

George Harrison discussed meeting Shankar at a dinner party for the North London Asian Music Circle all those years ago.

“His music was the reason I wanted to meet him. I liked it immediately, it intrigued me. I don’t know why I was so into it -- I heard it, I liked it, and I had a gut feeling that I would meet him. Eventually a man from the Asian Music Circle in London arranged a meeting between Ravi and myself. Our meeting has made all the difference in my life.”

Harrison discussed his own sitar playing.

“I’m not a very good one, I’m afraid. The sitar is an instrument I’ve loved for a long time. For three or four years I practiced on it every day. But it’s a very difficult instrument, and one that takes a toll on you physically. It even takes a year to just learn how to properly hold it. But I enjoyed playing it, even the punishing side of it, because it disciplined me so much, which was something I hadn’t really experienced to a great extent before.”

George went on to describe his earliest attempt at playing the sitar with the Beatles.

“Very rudimentary. I didn’t know how to tune it properly, and it was a very cheap sitar to begin with. So “Norwegian Wood” was very much an early experiment. By the time we recorded “Love You To” I had made some strides.”

In our exchange, Harrison put his sitar experiments with the Beatles in perspective.

“That was the environment in the band, everybody was very open to bringing in new ideas. We were listening to all sorts of things, Stockhausen, avante-garde music, whatever, and most of it made its way onto our records.”

In 1997 Ravi Shankar had released a new album, Chants of India via Angel Records, produced by his longtime friend and musical collaborator George Harrison. Chants of India is based on prayers and ancient chants of Shankar’s native India. The session musicians include Harrison, tabla player Bikram Ghosh and Shankar’s 15 year-old daughter, Anoushka, who helped assist and conduct and who was quietly gaining her own reputation as a dazzling sitar player in the shows she shares with her father.

In 1996, Angel Records issued the acclaimed 4-CD retrospective of Shankar’s career, Ravi: In Celebration. This compilation was produced by George Harrison and Alan Kozlowski in association with Ravi Shankar, and according to Harrison, “The idea behind this four disc set is to show the different aspects of Ravi’s music.”

The discs were arranged into Classical Sitar Music, Orchestral Indian/Ensembles, East/West Collaborations and Vocals & Experimental.

In our interview Harrison laid out how he first became involved with Chants of India.

“Steve Murphy, the president of Angel Records, had heard some songs that were similar to material on In Celebration, a Ravi retrospective that I had helped assemble last year. He suggested we go in to the studio to record more. This music, which is based on ancient Vedic chanting, I very much enjoy. And, of course, it gives me an opportunity to work with Ravi, so it made perfect sense.”

Harrison’s role on the record went beyond simply producing.

“I organized the recording of the album and during the recording I sang and played on a couple of songs. Bass guitar, acoustic guitar, and a few other things -- vibraphone, glockenspiel, autoharp. The main thing was organizing -- finding the right musicians, busing everybody out to my studio, and making certain everyone was properly fed. Finding the right engineer, John Etchells, was also key.”

When asked why now is the right time to release Chants of India to the world, Harrison was eager to explain his motivation.

“In a way it represents the accumulation of our ideas and experiences throughout our 30-year relationship. But to put it into a slightly more commercial aspect, the record label asked us to do this and that would never have happened 15 years ago. Because of the fact of multiculturalism has become more accepted, and more people are interested in what this music offers, this project has become more commercially viable. And this music is very close to me, this is something I very much wanted to do.

“I actively read the Vedic scriptures and I’m happy to spread the word about what this project is all about. People also need an alternative to all the clatter in their lives, and this music provides that. Whether it’s Benedictine Monks chanting or ancient Vedic chants, people are searching for something to cut through all the clatter and ease stress.”

In 1974 George Harrison gave a press conference in Beverly Hills at the Beverly Wilshire Hotel that I attended when he was preparing for a U.S. solo tour. George was asked about the Beatles, his Dark Horse record label and the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi. The results were published in the November 2, 1974 issue of Melody Maker.

“Biggest break in my career was getting into the Beatles. In retrospect, biggest break since then was getting out of them.”

Was he amazed about how much the Beatles still mean to people?

“Not really. I mean it’s nice. I realize the Beatles did fill a space in the sixties. All the people the Beatles meant something too have grown up. It’s like anything you grow up with you get attached to things.

“I understand the Beatles in many ways did nice things and it’s appreciated the people still like them. They want to hold on to something. People are afraid of change. You can’t live in the past.”

Harrison was also questioned about his goals of Dark Horse Records.

“There isn’t really a concept or goal. The goal in life is to manifest our divinity. Because each one of us is potentially divine. All we can do is try and do that, and hope that influences our work.”

In addition at that frenzied media event, Harrison cited the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi and his visit to Indian with the Beatles in 1967.

“I have a lot of respect for him. He gave me help and plugged me in to a method of being able to contact that reservoir of energy which is within us all, pure consciousness. I experienced it. He showed me how to reach that. Everything else is just words, beyond the intellect is to have an experience you have to have in order to know.”

How did George see the role of entertainer in working with causes and charities?

“I don’t think it’s an entertainer’s job. He does what he can. And I do it through music. It’s not isolated to musicians.”

In his 1974 Beverly Hills-based press conference, Harrison also discussed Ravi Shankar to the curious throng.

“India’s pop music is actually like the film music. Like every movie in India has about 18 tunes. And so that’s really what would be called the pip music. Although it’s a bit funny. You know it’s very strange. For my taste it’s the classical is better.

“In the West the classical music can become a bit to heavy or a bit stogy. Whereas in India it’s the classical music which is really the groovy music. The film music. There’s a lot of really nice music, nice arrangements, you know, combinations where you get drums and sitars and violins and orchestras. The whole thing pushed together. But it is very strange.

“This is something, like, Ravi Shankar is a composer. I mean he’s a human. He happened to have spent 8 or 10 years practicing and becoming a master of an instrument which once mastered is an obscure thing. And he spent 15 years doing one night stands. So now he has his audience. But people seem to only think of him as a sitar player when actually, you know, he’s a fantastic composer.

“That’s why since ’67 when I heard these orchestral things he did in India they just made me feel that in the West there’s more chance of people getting into the heavier sort of ragas that he plays solo sitar. Through this orchestration because, because it has to be a bit more fixed, even though it is based on the old ragas, it has to be more fixed because there are more people involved, you know.

“There’s still areas for improvisation but there’s lot of basic fixed patterns in there. And I think the combinations of instruments that people may not have heard, the ones with instruments they have heard I really get this feeling, and I may be wrong, this music is just going to blow everybody’s mind. Because they’re expecting him to come up there with his sitar and it’s gonna be something totally different.”

Harrison at the time itemized the charities he would be working with on his tour that year including, “a concert in Los Angeles for the Self Realization Fellowship. It was founded by Paramahansa Yogananda. He happened to be a big influence in my life. I’d like to repay him in a small way.”

In the late fifties, Shankar played colleges around Southern California and the Ash Grove club. Lakshami, the Los Angeles Indian restaurant near Irving and Melrose, presented his debut L.A. recital.

Shankar in 1965 was booked at a jazz club in Hollywood, The Manne-Hole, owned by drummer Shelley Manne on Cahuenga Ave. One afternoon Shelley invited drummers to the bandstand to play with Ravi and his ensemble. They burned out the stickmen by the evening.

Shankar and the Transcendental Meditation Center were responsible for the formation of the Doors.

It was during 1965, when John Densmore and Robby Krieger met Ray Manzarek at the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi’s Transcendental Meditation Center on Third Street in L.A.

“Robby and I went because LSD was legal and we were quite interested in our nervous systems, and knew we had to do this TM thing slowly,” Densmore explained to me in a 2007 interview.

“We go over there and I meet this little guy, Maharishi, and the ‘Love Vibe’ is very palpable. This is 30 people in a room. Then, a year or two later, I read that the Beatles are onto TM and our little secret is being spread worldwide. Great.

“Frankly, TM is the reason the Doors are together. TM glued together Ray, Robby, Jim and I.

“Jim didn’t meditate, Robby and I went and Ray was there. That’s where we met. One time Jim came and he wanted to look into Maharishi’s eyes…and Jim later said, ‘Well, he’s got something. I’m not gonna meditate but he’s got something.’ This was the first class in the country. We were two years ahead of the Beatles, thank you (laughs).

“The whole Eastern Indian thing, Ravi Shankar, via George Harrison and the Beatles saturated everything with paisley bedspreads sound wise. ‘The End’ was a raga tune.”

It 1962 Shankar founded the Kinnara School of Indian Music in Bombay, now Mumbai, and a second school in 1967 in Los Angeles.

“In spring 1967, Robby and I went to Ravi Shankar’s Kinnara School of Indian Music [on Robertson Blvd] in Los Angeles. When you’re students at the Kinnara School of Music, you get to sit on stage with the master at UCLA’s Royce Hall. Later Robby and I go see Ravi play at the Hollywood Bowl, and George is on stage.

“Ravi didn’t teach at the school, but he’d drop in and give a little lecture on Sublimating Your Sexual Drive Into Your Instrument.

“Ray had a previous relationship with World Pacific Records in 1965 when he was on the label with Rick and the Ravens and recorded for Dick Bock who owned the label, and released Ravi Shankar albums in the U.S. We got a couple hours of free studio time at World Pacific recording studios, and that’s when we got to make a demo in 1965,” John recalled.

“On the way into the World Pacific studio Ravi Shankar is leaving with Alla Rakha, my idol, who I didn’t know was going to be my idol yet, was on the way out with these little tabla drums, which I soon find out by studying at the Kinnara School, are the most sophisticated drums in the world. I’m in awe of them. It’s the East! And, I’m just a surfer. Not literally, but from West L.A.

“The very first TM class was with Clint Eastwood and Paul Horn the year before me. Paul later was in India with the Beatles. Harrison was doing it in England. Later, George Harrison came to one of our recording sessions for The Soft Parade.

“You hear the Indian thing in techno stuff now. That came in and it was deep and it’s still around. We need the East.

“Let me tell you, at our Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction, (Bruce) Springsteen came up to me and said, ‘I like your drumming. It’s so quiet and then you drop a bomb.’ Thank you, Boss. So maybe, 1966, 1967, I was noticing in the traditional Indian ragas you gotta wait for your climax. It’s not a quickie, you know. So that was the influence.”

“Before it was transcendental meditation it was called meditation,” Robby Krieger specified to me in a 2007 interview.

“My friend Keith Wallace had a brother, Pete, who actually went to India, in like, 1959. He went to find a guru in India and checked out all these guys and ended up with Maharishi over there and talked him into coming to California. And so the first meeting we had was at the house of Peter’s parents in Pacific Palisades. And there were maybe ten people. I still do it when I need it,” Krieger underscored.

“I first heard of Ravi Shankar the first time the Doors played in Berkeley at a theater. And that was 1966, probably. And John and I met these Indian guys. We were kind of into the Indian thing, and they suggested we check out this record by Ravi Shankar. I had never heard of him. It was a white album on the World Pacific label called Ravi Shankar In London. I just fell in love with it. I would go to sleep every night playing it and getting it into my brain. It really did affect my guitar playing quite a bit. There was an influence of Ravi on ‘Light My Fire’ and ‘The End.’

“John and I went to the Kinnara School of Music when it opened. Harihar Rao was the instructor. I took sitar lessons and John took tabla. I bought a sitar in New York at a little Indian store where you could get them. I had seen Ravi play many times, including up in San Francisco. And he was always amazing. The Hollywood Bowl concert was really good. I remember that. I loved seeing him in the concert films of Monterey Pop and The Concert for Bangla Desh.

The one thing I do remember when Ravi came to the school and talked to us. We asked, ‘What is the secret? What do you have to do to really be good?’ And he replied, ‘You have to give up sex…’

“Last century I saw Ravi at a recording studio with Bruce Botnick in Santa Monica. I got to talk to him a little bit and told him about The Doors and ‘The End.’”

One night in 1997 during a recording session, Ray Manzarek hailed Shankar. “The genius. The master. He opened the door to the East. The vibrations, the inner spirit of music.”

“I was real happy when Ravi Shankar started getting acceptance in the West, partly because of George Harrison going to India,” Ram Dass acknowledged to me in a 1997 interview, “and I had heard of Ravi in the very early 60’s when I was in India. I played the tanbora. I loved the Beatles’ music. I took acid to Sgt. Pepper.

“I loved the Doors. Some Eastern influences in their music. Jim Morrison was a poet. I liked the level of reality he played with. I like people pushing the edge and getting out of the linearity. I love that. And not in a kind of clever, studied way, but in an ecstatic experiential way. That’s what I love better. That’s what he tried to do.

“I was delighted of the East-West merger. I was so much a part of bringing Eastern stuff to the West that it all seemed obvious to me when it eventually started happening here, so I don’t think I was blown away by the time it happened, I had already done it in my own being. It wasn’t like ‘Someone is doing this!’ It was great to see someone doing it with such style and class.”

The Byrds had been exposed to Shankar’s LP’s and were former occupants of the landmark World Pacific studio where their sound was developed with record producer/co-manager Jim Dickson during 1964.

“Best record I heard in 1967 might have been John Coltrane’s Africa Brass, Byrds’ co-founder Roger McGuinn revealed to me in a 2007 interview.

“We were on the road, and I had bought a Phillips Cassette Recorder in London, and it was such a new invention at the time there were no pre-recorded cassettes on the market. But, I had a couple of blanks that I picked up. And we stopped somewhere in the mid-west, [David] Crosby knew somebody there, so we went over to this guy’s house, and he had the latest Ravi Shankar and Africa Brass. And, so, I guess this is music piracy, but I dubbed Africa Brass on one side of the cassette and Ravi Shankar on the other. And we strapped the cassette player to a Fender amp on the bus and we just kept turning the cassette over and over and listened to that thing for a month on the road.

“We loved that music, which influenced ‘Eight Miles High’ later. The break on ‘Eight Miles High’ was a deliberate attempt to emulate Coltrane, like sort of a tribute to him, if you will. We had heard Ravi Shankar earlier.”

Shankar, the Kinnara School of Music and George Harrison had a big impact on songwriter and record producer Russ Titelman, who co-produced Harrison’s 1979 solo album Thirty Three and 1/3.

In the late 60s, Titelman was a noted session guitarist in town, working on Phil Spector and Jack Nitzsche productions, including the Performance soundtrack. Russ also studied the sitar at Shankar’ facility and briefly met George Harrison on the premises. His good friend, future Little Feat leader Lowell George was also in regular attendance.

In early 1967 Shankar had signed a $5,000.00 contract for his Monterey International Pop Festival appearance before the endeavor became a non-profit venture and his existing agreement was honored by the promoters. Those funds helped open the Kinnara School of Music.

“I was drawn to the school because of George Harrison,” Titelman enthused to me in a 2012 interview. “And, because of ‘Within You Without You’ and Indian music. Lowell could pick up the sitar and play the thing. Other people were struggling to get their finger to do one thing. He was already playing. He could do it. Lowell was a flute player and a Japanese shakuhachi flute player. In fact Lowell could play anything that he picked up. I met Lowell at the Kinnara School of Music. I studied sitar for a year. George Harrison came by and we were briefly introduced. I would produce him years later.

“I was always a huge fan of what George Harrison did. Think about Sgt. Pepper without ‘Within You Without You.’

“This was music he introduced that some of us already knew about. ‘Cause I have always been a big movie fan and soundtrack fan. And I and my compatriots had already heard this music. They used to play these movies at the Los Feliz Theater. We knew about Ravi Shankar. We knew about Ala Akbar Kahn.

“So when it then appears on Sgt. Pepper George Harrison changed the course of musical history in the world by introducing an otherwise uninformed public to a whole world of music that otherwise they would have been aware of. He brings Ravi Shankar to the center stage. And, to me, Indian music is the most expressive, the most soulful and the most beautiful music of any music on the earth, these ragas and the expressiveness of it. You listen to Ala Akbar Kahn. I thought he was the greatest.

“In 1969 Lowell was playing with the Mothers of Invention and rehearsing Little Feat. Lowell and I became best friends. So we spent all our time together. And he was rehearsing the new band and played with Fraternity of Man with Elliot Ingber and Ritchie Hayward. He put together Little Feat. He had Roy Estrada and himself and rehearsing in this little room on Sunset Blvd. And Lowell played me the songs he was writing and I thought they were great. ‘Willin’’ and ‘Truck Stop Girl.’

“Lowell was going to sign with Gabriel Meckler’s Lizard Records label. And I said to him. ‘I don’t think that’s a good idea. Let’s go to Lenny (Waronker) at Warner Bros. Records. Let’s go to Lenny first.’

“So I took Billy (Payne) and Lowell after I called Lenny and told him I wanted him to hear this stuff. We went to his office, a little cubical, practically like the size of the cubical we used to write in, only a little bigger. And he had a miserable little spinet piano in there, not completely in tune. So Lowell, Billy and I went to the office. Lowell sat down, he brought a guitar. Billy played piano.

“They played ‘Truck Stop Girl,’ ‘Willin’’ ‘Brides Of Jesus.’ They got done doing those songs and Lenny said, ‘Go upstairs and make a deal with Mo.’ That’s how it happened. And that’s how innocent those days were, too. They didn’t have to do a showcase. Lenny said ‘Go make a deal with Mo.’ Lenny was like the best song man of anybody. He got it immediately. That was it.”

In 1970 Titelman first started working for Warner Brothers as a producer and then joined the label as a staff producer in July 1971.

“Because of George’s connection with Warner Bros. Records I met George again. I remember I got a phone call at the label and was told he was going to call and he was going to do a record. I remember my secretary called and said, ‘It’s George Harrison on the phone.’ And I ran into Lenny Waronker’s office, and I said to him, ‘George Harrison is on the phone. Should I take the call?’ ‘Of course! Go in and take the call!’ George mentioned he had these songs and was going to be making a record, ‘Why don’t you come over and listen and see what I have?’ I went to his house.

“I never really knew how George arrived at finding me at the label. I assumed that Lenny and Mo (Ostin) said to him, ‘Why don’t you use Russ.’ That would be my guess. But there may have been, because of these other things, like the Kinnara School of Music, an arrow, you know, that pointed to me in addition to that. But that would be my guess. I never really knew how he came to that decision. But I’m certainly glad he did.

“George and Olivia Harrison were witnesses when my wife Carol and I got married while I was making the Thirty Three and1/3rd album in England.

“My favorite thing on that record is ‘Your Love Is Forever.’ I love that song. In fact, in his book, I Me Mine, he gave me a little tip of the hat, because I’d listened to all his demos and he had that tune and only just the guitar part. And I said to him after I had listened to everything, ‘You have to finish this song. It’s too beautiful.’ So he did and wrote a lyric for it. And in the book he said that I made him finish it.

“I loved The Concert for Bangla Desh movie and soundtrack.”

In the seventies when I was a weekly music reporter for Melody Maker, Harrison personally arranged for me to attend a Ravi Shankar date and early sound check at The Roxy Theater in West Hollywood when he was proudly showcasing his Dark Horse Records/A&M label artist, Ravi Shankar.

In 1997 I was originally scheduled to interview Shankar over the telephone for HITS magazine, and then at the last minute, Ravi requested, after talking to “a special friend,” that I come down to his home in Encinitas for “a proper visit.”

Ravi Shankar was 77 years old at the time. He was residing in the beach community of Encinitas, near San Diego, where he lived with his second wife Sukanya, and his daughter and protégé Anoushka, who has been performing in concert alongside her father for the past few years. I knew Encinitas very well. I had graduated from nearby San Diego State University.

In our 1997 conversation, Ravi was eager to discuss his Chants of India CD, the 1996 Ravi: In Celebration box set, his friendship with George Harrison, producer Richard Bock, the Monterey International Pop Festival, Woodstock, the Concert For Bangla Desh, and many other topics, including his recording collaborations with jazz musicians and his series of meeting and talks with the legendary John Coltrane.

We took our shoes off and rolled tape for over two hours.

Q: Tell me about your Ravi: In Celebration.

A: I revisit the work on this (box set) collection. I listen and hear, “Oh, my God! It could have been a little better if it was like this...” I’m never totally one hundred percent satisfied with anything that I have done. I hear some of the items (on the box set) and I think of (producer/World Pacific Record’s owner) Dick Bock, or a restaurant on Vermont Ave. That happens a lot. I met such wonderful people when I first came to the U.S. to record in the mid-1950’s. Dick was such a lovable character who knew everyone. And everybody loved him.

The other person I met, I don’t know if you know him, is George Avakian (producer of Louis Armstrong, Johnny Mathis, Charles Lloyd), was at Columbia Records and took me to all the Miles Davis concerts. These two were my greatest friends. On this collection, without doubt, I missed a few of them, (Laughs), which are not included. There are at least four to six other box sets that can be made with all the things that have not been together. The (new) package is so beautiful, liner notes, and George was very enthusiastic.

Q: You literally were recording a few blocks from my parents’ house in the early 1960’s at the famed World Pacific Studios. I rediscovered the work you did with jazz musicians: Bud Shank, John Handy, and I know you composed the piece, “Rich a la Rakha” for Buddy Rich and your own tabla accompanist, Alla Rakha. And you gave lessons in Indian music to Don Ellis and John Coltrane.

A: I clicked with jazz musicians, always. From my childhood really, jazz reacted so strongly in me, because of the rhythms and beats and the freedom to improvise, which we also have. The whole basis is different because we improvise on the ragas and have very strict rules, whereas jazz takes chords, the harmony of Western classical music, and takes a theme and then they go free, whatever they want. But they don’t observe the raga or the complicated rhythmic cycles.

Q: I know John Coltrane was going to formally study with you before he died. He has a son, Ravi Coltrane.

A: He was coming to learn from me. I told him, “John, why do I find so much turmoil and disturbance in your music?” He laughed and said, “That’s exactly what I’m trying to find out myself and you can help me.”

We had three meetings and he came and sat twice, a very long one and a very short one in a New York hotel where I used to stay. And he wrote down many ragas, and I taught him how we improvise and he was asking me, “How do you bring the spiritual quality in your music? How do you do that?”

Afterwards, he started using more drones, if you remember. I heard the turmoil in his music. He was like a child. It was a wonderful revelation for me to see this man. Dick Bock always tried to play me as much Coltrane as possible, in the car, or a few records. There I was hearing certain melody qualities that were so wonderful.

Q: Your new CD Chants of India is produced by George Harrison. Can you discuss your relationship with George? You’ve been friendly for nearly a third of a century, and he’s always managed to help support your artistic desires and subsequent recordings.

A: He’s a very rare person...it is something so special. There are many other people who could do what George does, but they don’t have that depth. He’s so unusual. What has clicked between him and me, what he gets from me, and what I get from him, that love and that respect and understanding from music and everything, is really the most important thing. It’s not the money, or he helping me to record, that’s not the main thing. But it’s the very special bond between both of us. The idea for Chants of India was suggested by Steve Murphy (president of Angel Records). He mentioned the success of those Spanish monks. George was very enthusiastic after the idea was given. I was very much attracted to the whole idea, and so was George, as we have already said. I found going deeper into it, what a difficult job is was, because, you know, when you deal with something very traditional as those few thousand year old things, concept and the oral tradition that has been handed down by the family who chants. Also, considering that there have been so many recordings already done in different ways, from very pure to very raw. Very sophisticated from classical musicians singing the classical style of our ragas and melody forms and also done by a lot of commercial people in very strange modern concepts.

To make something so different from all these was a great job for me and a lot of responsibility. I had to keep it traditional, as well as be different. So, that’s how it took me some time to study a lot, to hear a lot and change my ideas again and again, to finally what we did.

The recording was done in different periods in time and places. Twice we did it in Madras, of course. Madras is in the southern part of India and a lot of tradition remains intact, you know. I took the help of traditional chanters who for centuries, their families have been keeping it intact. But I gave it a background of holding drone instruments like cello and the Indian instrument tambura and also some big bamboo flutes, doing very slow passages taking a particular raga. I didn’t play the sitar, but I strummed the sympathetic strings which are under diminished strings. All of that made it sound so different, but at the same time it did not sound so foreign.

A: The main intention, to tell the truth, because I have been very much disturbed by things that have been happening. You know, I could have done these chants in an entirely ritualistic, fundamentalist approach also, which any religion can do. But I was very conscious of this and wanted to make this so international and universal that this whole spiritual feeling comes out, even if you don’t know the meaning of the words. But we have done our best to keep the words with translations and everything, so that it helps and you will know that the mantras selected from traditional Vedic and Upanishad (ancient Indian spiritual texts) pertain to peace, love, happiness, well-being, health, mental health, spiritual health, and the goodness and prayers for nature and the planet.

I chose the special prayers, what we call mantras, which focus more on ecology, the atmosphere or whatever. What I did, I added the music into such a proportion that it does not overpower it, and the same time it helps in the background. Not making it Westernized, to make it palatable for Western people. But I did take help of cello, harp, violin, autoharp, thing that have a very celestial sound, along with the Indian bamboo flute and the tambura. But I didn’t use the sitar or the sarod, which I’ve done in the past in many of my recordings. These I avoided, I wanted to be completely different.

Q: Was it hard for you to make a recording without it being ‘sitar-driven’?

A: No. (Laughs). It is not. Because I have done lots of recordings and have made other play the sitar and used other Indian instruments like the sarod. In this one, I avoided those and kept in the background, something which is hypnotic and repetitive, mantras, along with what I call the three mystical and magical notes, which are the tonic, the lower note and the raised note. Which are the traditional system. And that has shifted into different pitches in the background, corresponding to the raga which fit those notes. That’s the only way I used the instruments.

Q: Why is the repetitive nature of mantras so powerful?

A: That’s what it is you know...The power of the mantras has always been because of the repetition. It has been scientifically explained by many people, which I cannot do. I achieve through the particular vibrations of those sound syllables, the repetition has tremendous effect and monotony always gives that high feeling, even if you listen to folk music, they go on repeating passages and sometimes it gets in a trance. So, mantras have tremendous power and even if people don’t understand it, they do. When you say “Ohm...” Close your mouth. “Ohm...” When you close he lips and put the sound louder, “Ohm...” Keep it as long as you can and feel the buzz! It does something to you... It has been proven to be very strong.

‘Ohm’ is something that can be practiced by anyone. The word Veda. There are four principle Vedas and later came many books which tried to explain each of these mantras and scriptures. They all tried to make interpretations, because it’s a very old language. The main four Vedas have been explained through all the letter scriptures. First oral tradition, then written on scrolls and given to the families. It was a very closely guarded secret, but now everything is open and published, read and people take it very lightly and think they know a lot, but it’s something very deep.

It was then that George came in the studio, while we were recording. His help started from then on in balancing, giving bass to particular things and mostly afterwards in the mixing. He was also very involved when we were in his studio at his home. On many of the numbers, I asked him to strum acoustic guitars, along with other instruments. It’s so subdued. He played some additional instruments and even joined the chorus, giving his voice. He was all the time there, that was one of the most beautiful things and very helpful in the mixing. We had such a fantastic experience. He does not impose his ego into the music. He never does that. That’s such a wonderful thing. He gives some suggestions like, “Use that particular voice a little louder than this one.” When I felt he was right, I said “Yes.” When I didn’t feel right, I said “No.” No problem of ego at all. He gave fantastic suggestions, especially when it came to the volume and the combination of cello and violins. We were together.

When we recorded it was fantastic. In Henley, at George’s studio, there was no problem. There’s no pressure when I go to his home and into his studio! It is so relaxed. No “Finish this at this time!” George went through the sequencing with me and agreed with what I made from the buildup when I did the programming.

We had a wonderful engineer, John Etchells, who was calm and beautiful. The musicians that we got in London were very good, and I had known some of them earlier from the schools. My wife and George’s wife Olivia were so helpful, my daughter Anoushka was helping me writing, conducting and talking to the musicians. There was no tension, like in Madras, you know, which was unfortunately so commercial. That was a big difference. My daughter is extremely talented and I was training her with this recording.

Q: Keep her away from Hollywood!

A: (Laughs). I know! I know! I’m trying my best. (Laughs) I see the growth and commitment in her studies. My daughter does Indian notation and she knows Western notation, because she is learning piano. This is how she started. She’s very fond of rock ‘n’ roll. You name it. MTV. She’s all around it. She’s out of this world from that point of it. A teenage magazine came for a modeling thing from India. Anoushka is the best student I have had for a long time. George adores her. He’s Uncle George. She is the right person to whom the sitar music must be passed.

Before, the destiny of women (in our culture) was to get married and to bear children, so naturally, they could not pursue music. But now they are pursuing, even if they get married, even if they have children, they are much more serious and the standard is very high.

Q: The June 1967 Monterey International Pop Festival. What are some of your memories of the event and getting the booking?

A: Dick Bock, of World Pacific Records, called Lou Adler. I was recording for World Pacific. Some of my recordings with jazz musicians are on that label. Dick was a wonderful person. Anyway, Monterey to me was like a revelation. Completely new. I had met George before that and that started the whole big hullaballoo, as you know. And, I saw the whole folk movement that started in England. That’s when I started seeing all the strange dress and the smell of patchouli oil, the hash and LSD. To me, it was a new world. Anyway, I had been performing in the United States since 1956. Carnegie Hall.

My first fans were jazz buffs and jazz musicians and average American people. So, a decade later, I arrive in Monterey and see butterflies and colors and flowers with peace and love. It was fantastic. I was impressed, but everyone was stoned. But that was all right and I was meeting all these beautiful people. Fine. It was one day before my concert and I went to hear the whole thing. That to me was the real experience. One night, I really heard Otis Redding. He was fantastic. One of the best, I remember. I really like The Mamas and The Papas. Lyrical, harmony and good choruses and harpsichord. Then, you know, came the hard rock. The Jefferson Airplane. The Grateful Dead. To me it was difficult in a very loud, hurtful in-my-ear way. And Janis Joplin. I had heard of her, but there was something so gutsy about her. Like some of those fantastic jazz ladies like Billie Holliday. That sort of feeling, so I was very impressed by her. Then, some others and what really disturbed me was the hard rock. The worst was to come.

I had heard so much about Jimi Hendrix. Everyone was talking about him. When he started playing...I was amazed...the dexterity in his guitar playing. But after two, three items, he started his antics. Making love to the guitar, I felt that was quite enough. Then, all of a sudden he puts petrol on his guitar and burns it. That was the leaving point. Sacrilegious. I knew it was a gimmick. Then, the Who followed, started kicking the drums and breaking their instruments. I was very hurt and ran away from there along with the others who play with me. My feelings were hurt deeply, as well as my respect for music and the instruments. We ran away from the festival.

I said at the time, “Please. There is a contract and whatever you want to fine me, I won’t play. I definitely will not play in-between any of these items tomorrow.” So, there were talks and meetings between Dick Bock and the festival people. The next day, in the afternoon, we set up a special section between 1:00-3:00 p.m. where there would be no one in front of me and after me.

It was cloudy, cool, it had rained a little and that’s when I played and it was like magic. Jimi Hendrix was sitting there. (Jerry) Garcia was there. I remember a few names. All of them were there and you can see on the film what magic it had. I was so impressed and it is one of my memorable performances. I didn’t plan for this. I was grateful to God that I was sitting in the atmosphere without anyone disturbing me. It drizzled for a few minutes and then it stopped. So, it was was cloudy and there were flowers from Hawaii and you know, what atmosphere! After my set, it was crazy. I have never felt such a commotion of this sort. I was so pure, in spite of the fact that there were many people who were also strong. But it didn’t matter, because the whole atmosphere was so clean and beautiful and I could give my best. That’s all I can say.

Q: You weren’t in the Woodstock movie, but a live album At the Woodstock Festival was released in 1970 on World Pacific Records.

A: I have always said that if Monterey was the beginning of this beautiful peace and love, flowers and all that, then Woodstock was the end of it. Because it was so big. Half a million people. Rain so much that there was mud all over. You couldn’t see the people or look into their faces. Such a distance and such a vast multitude. And it looked like a big parking place. We came by helicopter and landed behind the stage and it was raining. It was a mess. But, my commitment was so strong, because I couldn’t get out of it, so I did my best. And somehow, in that atmosphere, I did my best, but I couldn’t feel anything.

Q: Was playing outdoors or at festivals a stressful situation for you or the instruments you were playing? I know after Woodstock you stopped doing pop festivals.

A: For technical reasons, our instruments are so sensitive and delicate and weather affects pitch and completely ruins the sound and it becomes muffled. Out of control, out of tune. Even indoors, we have to be very careful not to have very strong lights. Heat, humidity affects the instruments. Now, all the halls have air conditioning. And we never have big concerts in summer or in the rainy season. The main concerts are all in the winter season, three or four months when it’s ideal weather, dry and cool. I don’t like playing outside very much, but there have been some wonderful outdoor places and performances like Tanglewood, because the weather was quite good and the great audience, and a few other places where the weather was just right.

Q: George Harrison played on the album Shankar Family & Friends which came out in 1974, and produced Music Festival From India in 1975, which featured soloists from India. You also shared billing on the Dark Horse tour of the U.S. and Canada in late 1974.

A: I’m glad you mentioned the Dark Horse tour, again, a wonderful attempt and a wonderful thing that George really planned. Unfortunately, what happened, and we had the first 45 minutes with 14 musicians, and believe me, I would safely say there were ten to fifteen percent of the crowd who came especially for us, the Indian crowd, and the American crowd. But, definitely, it was almost eighty to eighty-five percent which were for George and his group. So, it didn’t please either of the groups, if you see what I mean.

George, unfortunately, had a hoarse voice the whole tour. He had too much strain and he didn’t want to sing the old melodies, which people were crying for. What he wanted to do was sing his new numbers which he was so anxious to do. But it didn’t work with his hoarse voice, and because he didn’t sing the items that people were shouting and clamoring for. We had sell out audiences everywhere and no problem. We were so happy in the plane and happy travelling. The food cooked was Indian and it was fantastic. But people were not very happy. Either the audiences who came for me or for him. But...it was just one of those things, unfortunately.

Q: I know it might be awkward to you, but you have been integrated into the retail record and radio world as a ‘new age’ artist or in the ‘world beat’ category. Especially, in the last ten years. I realize it’s a marketing handle, but how do you feel about this area?

A: It was never my intent, but I got grouped into it for two reasons. Many people still don’t realize I had the fortune, or misfortune, of playing a double role all my life. One, as a very traditional, orthodox, purist sitar player representing the tradition of India, which connects with the ‘chants’ and everything.

Another side, I was exposed during my childhood with my brother, listening to all the symphonies and the best musicians in the world, jazz. I had this creative, inventive mind all the time, even after I went through all the training. So, I turned out to be a composer as well, which in our Indian music was a ‘No-no,’ or not usual. So, I had to go through this problem always, being mistaken for these two identities. People thought I was sacreligious to my music when I was trying out something with Yehudi Menuhin or Jean-Pierre Rampal, or George Harrison becoming my student, or doing music for some film, or writing scores for this symphony orchestra. I’ve had this problem, always. Leonard Bernstein had this same problem.

See, people like to box everyone, put them into a slot. In 1973-74, I did those two records with George and it went completely above most people’s heads. But, now, people are saying such beautiful things about them. It all came together during my 75th year with concerts in London, New York and New Delhi. George was so interested in producing (with Alan Kozlowski) and compiling the box set.

I had very strong about the concepts of In Celebration. That they shouldn’t mix everything so each record was according to the idea like the classical side, the orchestral and ensembles, the East-West collaboration, and the vocal and experimental.

Q: What do you want to give the audience when you perform?

A: I can only tell you what I’ve heard, not once, but a thousand times. It comes from a black man who is a porter at the airport, or the immigration officer, and they say one thing, which I always get tears in my eyes: “Thank you for what you gave us through your music.” Some go back to the Sixties, even 1956 or whatever, and this has always been the case. That’s what I want to do through my music. To give them, as much as is possible, love and peace and the feeling of all the different sentiments that we have, starting from romantic to playful, to happiness, to speed, to virtuosity and fun. And finally something which is most important to me, the spiritual.

Q: The Concert for Bangla Desh in 1971. I also know you had some conflicts after Woodstock and before the concert about playing in front of U.S. audiences. You had a problem with people in the audience being stoned and high. Correct?

A: It was terrible. My manager (at the time) had me committed to play and I went to clubs to perform. I didn’t know. There were tables, they were drinking. I said I will not play until you stop drinking, which they did and they accommodated me. But still the atmosphere...and they didn’t drink or smoke while I was playing, but they were already...I want the music to get people high. I had to take drastic steps sometimes. I walked off and left the stage with my sitar a few times where they had booked me. Then, I could not believe one time, people in front of me were masturbating and copulating and that was too much for me and I walked off. Then, they made stage announcements to behave and I came back and it was better. I backed away and stopped performing for a year and a half in the United States, until I got back some classical promoters because by that time my promoters were either rock or pop or folk. That was where my manager was booking me. So, I left that manager and completely stopped performing.

Q: How did the Concert for Bangla Desh even come about?

A: I told George and George wanted to help me. The film Raga was ready and it needed some finishing in which George helped. It was released, I believe, in 1972. At the time time, I lived in Los Angeles and had a house on Highland Ave. A beautiful Spanish villa and at that time, George was in town, and at that time I was planning to do a benefit concert for Bangla Desh, because I was very hurt that this whole thing was going on. To help this refugee problem, I wanted to raise some money.

Everybody, every Indian, was thinking about doing that. And then, when I thought about it, I knew I could do more than any other Indian musician. Still, how much can you send? $20,000? $25,000, at the most?

At this time of turmoil I was having, George was there. He came to meet me and I was sitting. He saw me. From 1966, whenever he came to town, we would meet. At that time, he was staying in L.A. for a couple of weeks. I told him what I was planning. You know, it’s like a drop in the ocean. At the same time, I never wanted to take advantage of him. I did not want to say, ‘Would you help me?’ But, somehow, it came very naturally. He was so sympathetic. ‘Well...let’s do something.’ And you know, that made me feel so happy. What he did, he immediately started phoning and booking things up.

Q: Was he good on the telephone?

A: (Laughs) Very quick. (Laughs) His position naturally makes it quicker. He phoned and got Madison Square Garden (in New York). Later he contacted Bob Dylan, Eric Clapton, Billy Preston, and a few of his friends. Somehow, it was done (Snaps his fingers), like that. Within three weeks or so, we gave a performance and it was sold out. So, they had to schedule a matinee. As you know, the first half was me. I called my guru’s son Ali Akbar Khan who play the sarod, and who know has a college in the Bay Area. Alla Rakha, now lives in Bombay, and he’s running a school for himself. We were the first part. I composed the first lines for the items played as we always do and we improvised. And then intermission.

There was no clapping when we were tuning, which is seen in the film and the people were so well-behaved, a lot of matches. It went beautifully. It was a young audience, especially because I had this existing audience already, who were mature listeners and who had come to Carnegie Hall. This audience was the same type of audience as Monterey, but they were very attentive and there was no problem at all. After our segment, I went to see the second half. Their program was very complimentary, because they chose the numbers that were very soulful in the sense that they weren’t hard rock. “My Sweet Lord,” “That’s The Way God Planned It.” Bob Dylan had his harmonica and did ballads. George sang “Here Comes The Sun,” and the song he composed “Bangla Desh.” There was harmony and it wasn’t so different. It went off beautifully.”

August 1, 2021 will be the 50th anniversary of two landmark benefit concerts that nearly 40,000 attended at Madison Square Garden in New York City on August 1, 1971.

“Really, it was Ravi Shankar’s idea,” answered Harrison in a press conference in July 1971. “He wanted to do something like this and was telling me about his concern and asking me if I had any suggestions, Then after an hour he talked me into being on the show. It was a question really of phoning the friends that I knew and seeing who was available to turn up. I spent one month, the month of June and half of July just telephoning people.”

Harrison subsequently organized two refugee relief charity concerts while composing, recording and releasing a studio single, “Bangla-Desh,” that was available just before the heralded affair.

At the performances, Harrison and his pals offered stellar renditions of “Wah-Wah,” “Here Comes The Sun,” “Something,” “While My Guitar Gently Weeps,” “My Sweet Lord, “Just Like A Woman.” “Blowin’ In The Wind” and “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall.”

The two concerts on 1 August 1971 were successful, garnering U.S. venue proceeds for $243,418.50 donated to UNICEF while also raising awareness and visibility for the organization around the world.

The shows were recorded by Phil Spector and engineer Gary Kellgren with the music produced by Spector and George Harrison.

American documentary film director and producer Saul Swimmer directed the movie. Swimmer had served as co-producer of the Neil Aspinall and Mal Evans-produced Beatles documentary Let It Be in 1970.

“The Concert for Bangladesh (originally titled The Concert for Bangla Desh) initially was a live triple album commercially released in retail outlets just before Christmas in 1971 in the U.S. and after New Year's Day 1972 in the U.K.

Richard Williams in the January 1, 1972 issue of Melody Maker proclaimed “If you buy one LP in 1972, make it this one.”

It immediately became a bestseller, landing at #2 for several weeks in the U.S. charts and becoming George Harrison's second #1 U.K. album.

The multi-disc soundtrack set won the Grammy Award for Album of the Year of 1972 for music producers Harrison and Phil Spector.

Eventually millions of dollars were given to UNICEF who distributed milk, blankets and clothing to refugees.

George Harrison would set up his own charity foundation, The George Harrison Fund for UNICEF, after he became frustrated with red tape and bureaucracies that had slowed down the process of spreading monies intended for recipients.

The George Harrison Fund for UNICEF is a joint undertaking between the Harrison family and the U.S. Fund for UNICEF to support UNICEF programs that provide lifesaving assistance to children, including health, education, nutrition and emergency relief. In the tradition established by George Harrison and Ravi Shankar, The George Harrison Fund for UNICEF continues to support UNICEF programs in Bangladesh while expanding its influence to include other countries where children are in need.

Apple Corps/Capitol in October 2005 re-released The Concert for Bangladesh-George Harrison and Friends on CD and DVD to celebrate the 35th anniversary of this collaborative event. https://lnk.to/ConcertForBangladesh

The DVD includes the original 99-minute film restored and remixed in 5.1, as well as 72-minutes of extras.

There is also previously unseen footage: “If Not for You,” with George and Bob Dylan from rehearsals, “Come On In My Kitchen” featuring George, Eric Clapton and Leon Russell at the sound check and a Bob Dylan performance from the afternoon show of “Love Minus Zero/No Limit,” not included in the original film.

The extras feature a 45-minute documentary directed by Claire Ferguson and co-produced by Olivia Harrison. The Concert for Bangladesh Revisited with George Harrison and friends, about the background to the event with exclusive interviews and contributions from Sir Bob Geldof, and United Nations Secretary-General Kofi Annan, who stated, “George and his friends were pioneers.”

In the documentary, Leon Russell reflected, “It was just one high level of experience from beginning to end.” While Eric Clapton readily admitted, “This will always be remembered as a time that we could be proud of being musicians. We just weren’t thinking of ourselves for five minutes.” Ringo Starr added, “The beauty of the event came across and the audience was so great.”

The Concert for Bangladesh was one of the first benefit concerts, along with the earlier 1967 Lou Adler and John Phillips produced Monterey International Pop Festival that brought together an extraordinary assemblage of major artists collaborating for a common humanitarian cause – setting the precedent that music could be used to serve a higher cause. The Concert for Bangladesh has been the inspiration and forerunner to the major global fundraising events of recent years proceeding Live Aid by 14 years.

Chris O’Dell of Apple Records was instrumental in helping George Harrison contact the musical talent for The Concert for Bangladesh in a Nichols Canyon house George rented with wife Pattie Boyd in the summer of 1971.

“The first line of thinking from George was ‘Ravi has asked me to do something for him,’” remembered O’Dell in a 2011 interview we did.

“That’s about friendship. That was more important than where it was gonna go. Even in the lyric to the song ‘Miss O’Dell,’ George had mentioned ‘the rice (that never made it) to Bombay.’ George had told me about that situation earlier that summer. George was learning a lot from Ravi as time went by. So the idea of a concert didn’t come up right off the bat. It came up later. Then it was, ’would you help me?’ And it was little things. Don Nix came into town. George didn’t know him. We all went to Catalina Island together. I knew him from Leon. From that came the background singers.

“I don’t think we had any idea of what it could be. I mean, it was fairly apparent that if you put a Beatle on stage, with a successful album behind him, All Things Must Pass, that it would probably draw people especially. John & Yoko did their things, but George hadn’t, and you make an assumption that with George involved it’s gonna draw people.

“George said, ‘I can’t believe this is all coming together.’ The whole thing just grew right before our eyes.”

O’Dell also described Harrison’s mission in securing Bob Dylan to the summit.

“That was part of the territory with him for a long time. And, you know, honestly, if George had an idol musically, that was it. So I think just having that piece there. George looked up to Bob in a way that there was that kind of esteem, and then the asking him to do something like that, and not wanting to let him down. George was really frightened by all this.”

It was well documented that George, Pattie and Chris all had concerns about Bob Dylan even showing up at the Bangla Desh gig, although all were immediately relieved when Dylan arrived at the rehearsal.

O’Dell and Boyd were backstage for all the action and caught the second show in second row center-stage seats.

“I first heard Ravi at age 19,” volunteered drummer/percussionist Jim Keltner in a 2020 phone interview. “We used to sit around and listen to Ravi and Stravinsky in the days when we were trying to expand our consciousness. When Ralph J. Gleason wrote about Miles Davis he’d sometimes mention Ravi. I became well aware of him.

“And, then, years later to have actually recorded with him when George asked me to be part of his album Shankar Family & Friends. And to be on tour with George and watch Ravi in 1974 and the most amazing musicians on the planet every night was a thrill beyond. Every night on the plane I would sit next to Alla Rakha while he was having a Scotch. He didn’t speak English at all and he would sing the tabla rhythms to me.

“Over the decades I got to see George and Ravi a lot together. It was a father and son relationship in a way. He brought Ravi to the rest of the world in a very big way. One of my favorite things was being with George in the audience watching Ravi play. The last time was in London.

“Sitting there next to George watching Anoushka play first, and dazzling everyone with her tremendous technique, and all these flashy things, and thrilling the audience. And then the old master. Her father, makes everybody just sigh with a few well-chosen notes. It was a perfect picture of exactly what you need to learn about in life, about youth, age and wisdom, technique, soul and all that. And George was at the wheel taking us there.”

I talked to Jim one evening over dinner at his home in Los Angeles for a 2002 Goldmine Magazine interview.

In our conversation Keltner reminisced about Delaney and Bonnie, participating in The Concert for Bangladesh and his relationship and friendship with Harrison and record producer Phil Spector. I had been one of the percussionists and handclapped with Rodney Bingenheimer on a couple of Spector-produced recording sessions with Jim on Gold Star studio dates with the Ramones and the Paley Brothers in the late seventies.

Delaney & Bonnie’s 1969 debut LP, Accept No Substitute made a big impression on both George Harrison and Eric Clapton. A&R man David Anderle had witnessed this white soul outfit gigging in West L.A. and brought them to Elektra Records to supervise their album produced by Delaney Bramlett. Billy Mundi and Jeff Simmons, during their Frank Zappa and Mothers of Invention employ auditioned for the band as well as Duane Allman. George Harrison made attempts to sign Delaney & Bonnie to Apple Records in the U.K.

“Leon is all over that,” reiterates Keltner. “His piano playing on the ‘The Ghetto’ is the greatest. No one else can do that. When I got to know John (Lennon) he told me he liked the Delaney & Bonnie and Friends Accept No Substitute album,’ Keltner marveled.

Jim in my 2009 book, Canyon of Dreams The Magic and the Music of Laurel Canyon touted his stint with Delaney & Bonnie. “We were doing a whole new soul thing that wasn’t Stax,” stressed Keltner. “We cut it at Elektra Studios on La Cienega. Leon Russell and Delaney Bramlett gave me a lot of confidence that I could play rock ’n’ roll, coming from jazz. And I was with my good friends Bobby Keys (sax player) and Carl Radle (bass player). Bonnie wasn’t doing Janis Joplin or Tina Turner. She was doing more of a hillbilly, gospel, blue-eyed soul kind of thing.”

Keltner further commented about Delaney & Bonnie and The Concert for Bangladesh. “Leon Russell made it great to be there. I had played with Leon on quite a lot of stuff: Gary Lewis and the Playboys, Delaney & Bonnie and Friends, Joe Cocker and Mad Dogs and Englishmen. Leon played on a lot of Phil’s great records.”

“After the earthquake in February of 1971 in Los Angeles, I told my wife, ‘Get the kids together and get on over here.’ We were there at a flat in Chelsea for a couple of months. During that time, George introduced me to Ringo and I played maracas on the single he produced for Ringo Starr at Trident Studio, ‘It Don’t Come Easy.’

“I was staying at Eric Clapton’s and the phone rang early one morning I picked it up since I was the only one awake. It was Phil Spector. He asked if I wanted to come down and play. So I said ‘sure.’ I borrowed a drum set from Colin Allen who was in a band, Stone the Crows. We became good friends and he helped me out a lot in those days,” recounted Jim.

“The first song we did that night was ‘Jealous Guy.’ George (Harrison) was there as well. We next did ‘Don’t Want To Be A Soldier.’ Playing on ‘Jealous Guy’ was one of those moments when you feel you are in a dream, especially later during playback in a room with John, Yoko, George, Phil Spector, Klaus Voorman and Nicky Hopkins all listening.”

Keltner worked on the Spector-produced John Lennon Imagine album, “Happy Xmas (War Is Over)” and later John’s Rock and Roll LP. Jim also appears on George Harrison’s Living In a Material World.

“George was on top of it during that time. He was very clean and he was meditating and doing the worry beads and all that. He was probably at his physical best at that time. He was always talking music. I learned a lot from George about the American rock scene. He introduced me to my own scene. That happened because I wasn’t familiar with it. I wasn’t in to rock and roll. I came out of jazz in the ‘60s. George was a very important teacher to me at that time. Georgie. My friend and my beautiful and wonderful brother. And I read these things about him being kind of anti-celebrity and all that. I guess he had enough of that with the Beatles, ya know, so that the Bangladesh event seems like a warm and wonderful cause that everyone turned out for.

“The Concert for Bangladesh concerts were in August, and the previous March, I did a couple of songs with Leon, Carl Radle, and Jesse Ed Davis for Bob Dylan, “Watching The River Flow” and “When I Paint My Masterpiece.”

“George called and said, ‘Let’s do a single.’ So we went in to Wally Heider’s studio 4 on Cahuenga in Hollywood and did “Bangla Desh” with George and Phil Spector. Leon played and I think he helped arrange the song. The birth of the concert sort of started with this single. I loved the song.”

For the two Bangla Desh shows at Madison Square Garden, Keltner is double drumming with Ringo Starr, who was asked by George to play and accepted on the condition “but only if Keltner will do it with me.”

Starr hadn’t played in front of an audience in a while, either. Keltner was asked to participate and he replied, “of course, but I want to stay out of his way.”

“Well, I think Ringo was asked by George, and Ringo said yes, ‘but only if Keltner will do it with me,’ because Ringo was a little unsure, about playing live with a big band. He hadn’t played live in a while, either. So, when they asked me I said ‘of course, but I want to stay out of his way.’

“I didn’t want to destroy anything of that great feel or his sound. When we actually sat down to play, I asked them to set me up in such a way that I could see his hi hat hand. And after we played together at the sound check I had to decide on a few things. And one of the first decisions I made was to not play the hi-hat much. So I played the hi-hat like I had seen Levon (Helm) of The Band do, which was to pull the hand off the hi-hat for the two and four, so that it didn’t come down with the backbeat at the same time. And that helped me stay out of Ringo’s way.

“Ringo was a little on edge,” volunteered Jim. “He didn’t fancy playing alone and was kinda unsure about his playing. Which is amazing if you think about it. One of rock’s all-time great drummers. All you have to do is listen to the Beatles records, of course, especially, the Live at the BBC. Rock and roll drumming doesn’t get any better than that. Earl Palmer, Hal Blaine, Gary Chester, Fred Below, and David ‘Panama’ Francis, great early rock and R&B drummers, and Ringo fit right in there with those guys.

“Listen to the BBC tapes and you’ll hear what I’m saying. Playing on Bangladesh was a really big deal for me. I made sure to stay completely out of Ringo’s way and just played the bare minimum.

“For Bangladesh there was only one rehearsal,” recollected Jim. “The rehearsal was in a basement of a hotel, or near the hotel. George was beside himself trying to put together a set list and trying to find out if Eric (Clapton) was going to be able to make it, Where Bob (Dylan) was gonna make it. Plus, George was nervous because he hadn’t played live for a long time. He was absolutely focused and fantastic as a leader. Of course he had Leon in the band. And Leon helped with the arranging and all. I remember that everything seemed to be fine at the sound check and that I didn’t have too many concerns. When we started playing with the audience in the room it really did come alive.”

“I remember loving the sound of Madison Square Garden. I heard Phil’s voice over the speakers, but never really saw him at the actual show, except during sound check. He was in the Record Plant (recording) truck.

“Phil had his hands full and did a remarkable job if you really think about it. Horns, multiple singers, double drums, lots of guitars. That was his forte, so he wasn’t intimidated by two drummers and 14 background singers. On Bangla Desh, George was very lucky to have had Phil on that set,” reinforced Jim.

In my 2004 book This Is Rebel Music, Keltner revealed, “George was absolutely focused and fantastic as a leader. Of course he had Leon (Russell) in his band. And Leon helped with the arranging and all. I remember that everything seemed to be fine at the sound check and that I didn’t have too many concerns. When we started playing with the audience in the room it really did come alive. George seemed very powerful that night.

“When George (Harrison) introduced Bob (Dylan) I stood backstage, and Dylan walked on. Jean jacket, kind of quiet the way Bob always is. Bob walked by me on his way to the stage. I had already recorded with him a couple of months earlier and I sort of knew him.

“He walks out there on the stage with that little jean jacket on and puts the harp up to his mouth and starts singing and playing and chills up and down my arms. His voice and the command. It was awesome. And Leon decides to go up with his bass for ‘Just Like a Woman,’ and play with him. It was a tremendous moment. It was real dark on stage with a little light for them. Dylan was incredible. Standing in the back in the dark, it was great to see Leon have the guts to get up there with the bass and perform with him on ‘Just Like a Woman.’

“Between shows the hotel had an incredible hospitality room set up with delicious Indian food.”

The late bass player Carl Radle played on the Leon Russell portion of Bangla Desh.

“Carl was one of my closest friends,” lamented Keltner. “James Jamerson, Paul McCartney and Carl Radle- I always thought were the guvs. Carl was the first bass player I started playing rock ‘n’ roll with. The good fortune and luck of that?

“George seemed very powerful that night. When you look at the picture of him then, he was really thin, ya know. But he was very powerful, and the songs: ‘My Sweet Lord,’ ‘Awaiting On You All,’ ‘Beware Of Darkness,’ ‘While My Guitar Gently Weeps,’ Wah-Wah,’ and ‘Bangla Desh.’ Some great stuff. And very appropriate for the suffering going on over there. And don’t forget Billy Preston with ‘That’s The Way God Planned It.’ I loved being a part of that with George.

“Bangladesh was a great little reunion. They loved playing with Ringo and me. Klaus Voorman was the principal bass player on Bangladesh. Phil loved the way Klaus played. He had a great way of stretching the time. Klaus is one of the greatest bass players I’ve ever played with. His playing was always just exactly right for the song. He didn’t have that much in the way of chops but he made up for that with his great musical sense.”

Guitarist Jesse Ed Davis is also seen and heard during Bangladesh. Davis worked with Keltner and Spector on the concerts, as well as Lennon’s Rock and Roll album. “Jesse Ed was the only guitar player who ever made me cry,” sighed Jim.

“I was right in the back watching Ravi Shankar’s set. The whole thing and being amazed and just how powerful it was. I had been listening to Ravi and Alla Rahka for years and here I was seeing them up so close I could reach out and touch them. Alla Rakha and Ravi Shankar were telepathic. They played together for so many years it was awesome to watch it. Ravi was at his peak in terms of technical proficiency. Alla Rakha was as well. It was dazzling. It is something that will always be with me. They did a longer set then what was actually recorded.

“Years later the cameraman on the Bangladesh movie told me, ‘you really caused me some problems when I was editing that film because your hand coming up like that I could never tell whether I was on the cut.’

“In fact, one night at Record Plant recording studio when somebody asked John did he see The Concert for Bangladesh movie? John said he went to the premiere and when he saw my face on the screen for the first time he stood up and yelled “-Hey-that’s me drummer!’ I fell on the floor.”

One afternoon at The Ash Grove club in West Hollywood, Ca. in 1971 Phil Spector lectured, disclosing a Concert For Bangladesh Bob Dylan story to the adoring throng.

“Nobody really knew Bob Dylan was coming, including us, ‘cause he was out bicycle riding most of the morning. The funniest thing, we were all sitting in the hotel room and George said, ‘Bob, do you think…it would really be groovy if you’d just come out one time and do a bit of ‘Blowin’ In The Wind?’ Just turn them all on, you know.’ ‘Ummm, man, you gonna do ‘I Want To Hold Your Hand?’”

In a 1971 radio interview on Los Angeles AM radio station KDAY, Spector previewed selections from his first generation Bangladesh master tape acetate.

Phil and the deejay aired Bob Dylan’s “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall” from the concert as well as Dylan’s non-released “Love Minus Zero/No Limit,” left off the package due to vinyl space limitations of the period.

“Bob just came in right from bicycle riding on the day of the show. Bob just got up there and sang. It was probably the best performance he’s ever done. In my opinion the album is worth buying just for Bob Dylan. And I’m not just trying to sell the album but it’s such an extraordinary performance.”