Photos courtesy of Apple/UMe

Revolver: The Beatles’ 1966 album that changed everything. Spinning popular music off its axis and ushering in a vibrant new era of experimental, avant-garde sonic psychedelia, Revolver brought about a cultural sea change and marked an important turn in The Beatles’ own creative evolution. With Revolver, John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison, and Ringo Starr set sail together across a new musical sea.

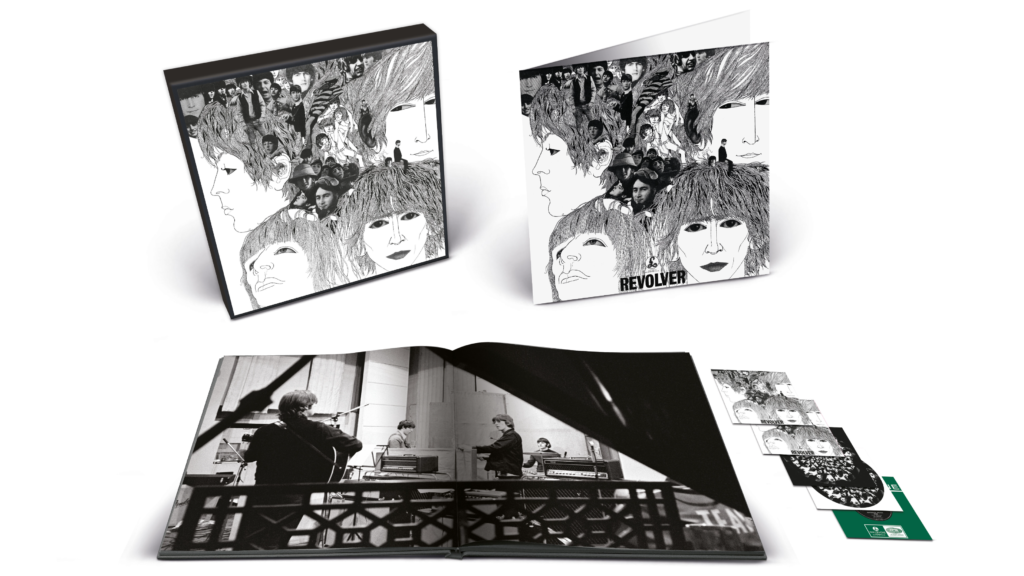

On October 28, Revolver will be released worldwide in a range of beautifully presented, newly mixed and expanded Special Edition packages by Apple Corps Ltd./Capitol/UMe. The Special Edition’s new stereo and Dolby Atmos mixes of the album’s opening track “Taxman” make their digital release debuts with today’s announcement and preorder launch.

A press release from A-Side Media Relations LLC provides a lengthy description of the history of Revolver and the new retail configurations.

“The Revolver album’s 14 tracks have been newly mixed by producer Giles Martin and engineer Sam Okell in stereo and Dolby Atmos, and the album’s original mono mix is sourced from its 1966 mono master tape. Revolver’s sweeping new Special Edition follows the universally acclaimed remixed and expanded Special Editions of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (2017), The BEATLES (‘White Album’) (2018), Abbey Road (2019), and Let It Be (2021).

All the new Revolver releases feature the album’s new stereo mix, sourced directly from the original four-track master tapes. The audio is brought forth in stunning clarity with the help of cutting edge de-mixing technology developed by the award-winning sound team led by Emile de la Rey at Peter Jackson’s WingNut Films Productions Ltd. The physical and digital Super Deluxe collections also feature the album’s original mono mix, 28 early takes from the sessions and three home demos, and a four-track EP with new stereo mixes and remastered original mono mixes for “Paperback Writer” and “Rain”. The album’s new Dolby Atmos mix will be released digitally.

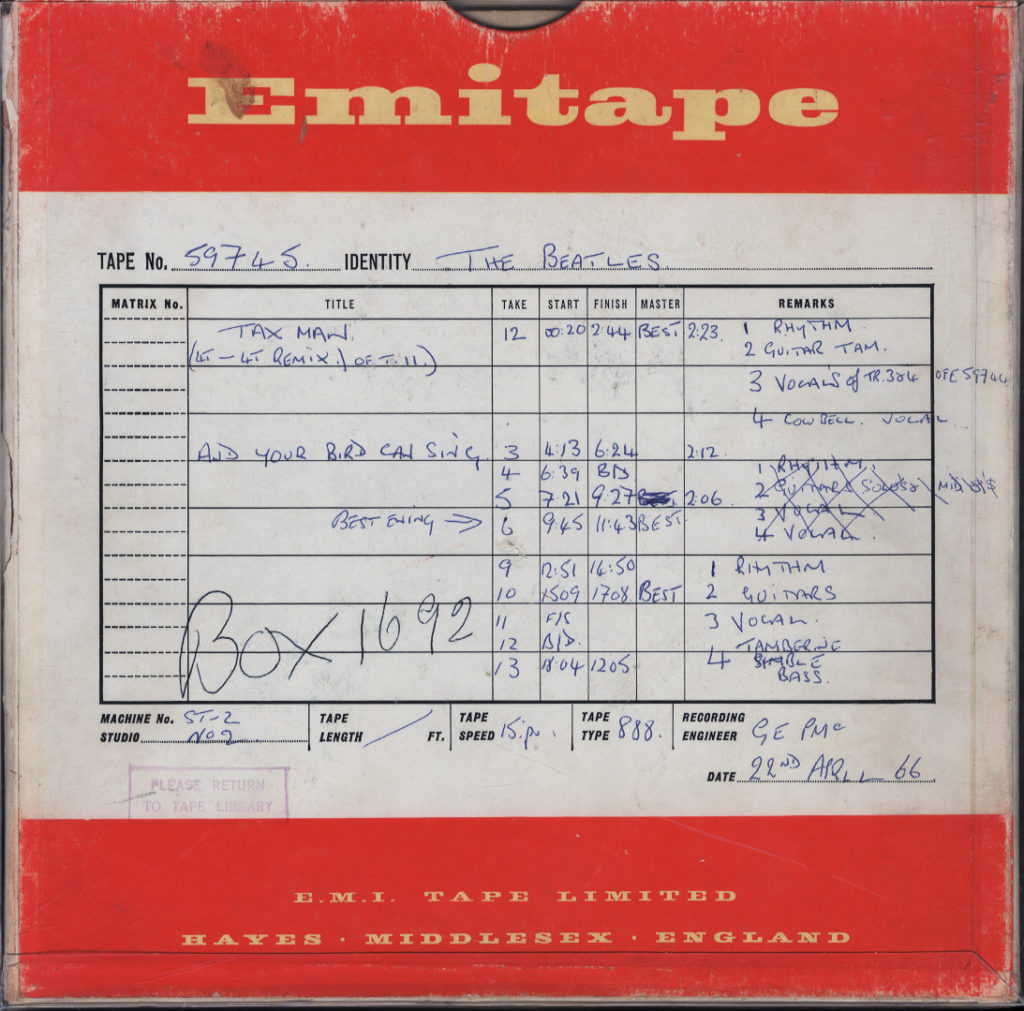

Across all the configurations, Revolver’s Special Edition showcases the GRAMMY-winning original album artwork created by The Beatles’ longtime friend, German bassist and artist Klaus Voormann. The Super Deluxe CD and vinyl collections’ beautiful book features Paul McCartney’s foreword; an introduction by Giles Martin; a thoughtful, enlightening essay by Questlove; and insightful chapters and detailed track notes by Beatles historian, author, and radio producer Kevin Howlett. The book is illustrated with rare and previously unpublished photos, never before published images of handwritten lyrics, tape boxes, and recording sheets, as well as 1966 print ads and extracts from Voormann’s graphic novel, birth of an icon: REVOLVER.

Following the December 1965 release of their groundbreaking album, Rubber Soul, and after wrapping up that year’s tour dates, a late decision to cancel shooting plans for a third Beatles film, A Talent For Loving, would have a significant effect on the creation of Revolver. The time allocated for filming and recording songs for a soundtrack was removed from the band’s schedule, allowing the group to take a four-month break before the Revolver recording sessions began. “One thing’s for sure,” John said a few weeks before the band’s return to the studio, “the next LP is going to be very different.”

On April 6, 1966, The Beatles gathered in Studio Three at EMI Studios (now called Abbey Road Studios) for their first Revolver recording session. With their producer George Martin flanked by recording engineer Geoff Emerick and technical engineer Ken Townsend, they went in blazing, starting with “Tomorrow Never Knows”. John’s ethereal vocals (fed from his mic through a rotating Leslie speaker), innovative tape loops – including Paul saying ‘ah, ah, ah, ah’, which when sped up produced a sound similar to a seagull’s screech – converge with Ringo’s thunderous drum pattern, George’s tamboura drone, and a backwards guitar solo. “Tomorrow Never Knows” propelled The Beatles and popular music into exciting new terrain. In an interview before Revolver’s August 5, 1966 release, Paul explained to NME, “We did it because I, for one, am sick of doing sounds that people can claim to have heard before.” Revolver’s Special Edition also features The Beatles’ first take of “Tomorrow Never Knows” from the April 6 session and a mono mix that was issued on a small number of records before the LP was recut with the correct version.

The next day, The Beatles returned to Studio Three, completed most of their “Tomorrow Never Knows” recording, and started work on the first version of “Got To Get You Into My Life”. As heard on the Special Edition’s Sessions One, this recording sounds very different from the released track. Revolver’s Special Edition also spotlights two more stages of the finished track’s evolution: an unreleased mono mix and a special mix highlighting the overdubs of three trumpets and two tenor saxophones.

One of George’s most important songwriting influences is heard in “Love You To”. The previous year, his deepening interest in Indian music and learning how to play sitar had brought him together with Ravi Shankar, who became his close friend and occasional musical collaborator. The Beatles began recording “Love You To” in Studio Two on April 11, the third anniversary of the UK release of “From Me To You”. Taken with the whole of Revolver, the short three-year span between these songs illuminates the band’s astonishing creative progression. “It was one of the first tunes I wrote for sitar,” George later recalled. “This was the first song where I consciously tried to use the sitar and tabla on the basic track.” With George on sitar and vocals, Paul on tamboura and vocal harmony, and university student Anil Bhagwat on tabla, the song’s intricate arrangement began to take shape over several takes. Overdubs included an additional harmony vocal by Paul, omitted from the released version but now faded up in a mix of Take 7. Revolver’s Special Edition also features Take 1 and a previously undocumented and only recently discovered rehearsal for the song with George playing sitar and Paul on tamboura.

Between April 13 and 16 in Studios Two and Three, The Beatles recorded their chart-topping “Paperback Writer” single (with layered harmonies, riffing guitars, and Paul’s booming bass lines) and its B-side “Rain” (achieved with tape machines slowed down for the recording and mixing processes). Prior to the single’s release on June 10 (May 30 in the U.S.), The Beatles spent a couple of days away from recording to shoot several promotional films for both songs with director Michael Lindsay-Hogg, who would later direct the Let It Be film. In addition to the songs’ new stereo mixes and original mono mixes, Revolver’s Special Edition features “Paperback Writer” Takes 1 and 2 – Backing track and two versions of “Rain” Take 5: one at the actual speed The Beatles played it and the other, a slowed down evolutionary mix used to create the master tape.

The album’s opening track, “Taxman”, was recorded across three Studio Two sessions in April and May. One of three songs on the album by George, in “Taxman” he expresses his frustration with the UK’s ‘super-rich’ tax rate at the time (90%), with a vocal wink to the “Batman” TV theme song. In a 12-hour session on April 20, The Beatles recorded and mixed the first version of “And Your Bird Can Sing” (for this song, the Special Edition features two Version One/Take 2 recordings and Version Two’s Take 5), then began recording “Taxman”. They returned to the song the next day, laying down George’s foundational guitar, Paul’s bass and his dynamic, raga-style guitar solo, and Ringo’s drums and cowbell. Revolver’s Special Edition also features Take 11, with falsetto backing vocals by John and Paul with different words from the released version.

“Yellow Submarine” was recorded on May 26 and June 1 in Studios Three and Two, respectively. The iconic, sunny rite of singalong passage for children everywhere and a favorite for the young-at-heart began quite differently than it finished. Parts 1 and 2 of the Special Edition’s songwriting work tape for “Yellow Submarine” reveal the song’s evolution from a rather sad verse sung by John over acoustic guitar – “In the town where I was born / No one cared, no one cared…” – to its adaptation by John and Paul to suit the jollier subject matter of the chorus. Revolver’s Special Edition also includes “Yellow Submarine” Take 4 and highlighted sound effects (a complex and merry sonic seascape, including Mal Evans’ sand-shoveling and Brian Jones’ glass-clinking) for listeners to journey with The Beatles through the song’s progression. “We were really starting to find ourselves in the studio,” Ringo explained later. “The songs got more interesting, so with that the effects got more interesting.”

The Beatles’ final Revolver recording session took place in Studio Two on the evening of June 21, 1966 into the wee hours of June 22, just one day before the band traveled to Munich to start their international summer tour. The lyrics for “She Said She Said” drew upon the memory of a disorienting day of misadventure The Beatles had experienced in Los Angeles. Having received George’s help to create a whole new song from some unfinished fragments, John led the group through the rehearsals and recording while the clock ticked away the last remaining session time. Revolver’s Special Edition also features John’s home demo for the song and Take 15 – Backing track rehearsal, with its introductory speech revealing convivial banter between The Beatles as they worked out the arrangement (later praised by composer and conductor Leonard Bernstein as “remarkable” with “real inventions”).

By 4am on June 22, The Beatles finished “She Said She Said”, wrapping up their Revolver recording sessions. The album’s final mono and stereo mixes were completed that evening, and the next day The Beatles were once again off and running on tour. They would next return to Abbey Road in November 1966 to begin recording Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.

Released on August 5, 1966, Revolver spent seven weeks at number one on the UK albums chart, and a double A-side single with “Eleanor Rigby” and “Yellow Submarine” topped the UK singles chart for four weeks in August and September. In the U.S., Capitol released an 11-track version of Revolver, which spent six weeks at number one on Billboard’s albums chart. “I’m Only Sleeping”, “And Your Bird Can Sing”, and “Doctor Robert” had been previously plucked from the sessions for Capitol’s North American release of the Yesterday And Today compilation album in June. That album’s sleeve was originally printed with the infamous “butcher cover” before pre-release controversy resulted in Capitol recalling and re-covering well over one million mono and stereo LPs with an innocuous photo of The Beatles gathered around a trunk.”

Otherworld Cottage Industries in 2014 published my book, It Was Fifty Years Ago Today (The Beatles Invade America and Hollywood).

Enclosed are personal and technical reflections on the initial Revolver 1966 release from my conversations with Geoff Emerick, Ken Scott, George Harrison, Ravi Shankar, Ram Dass, Steven Van Zandt, Rodney Bingenheimer, Daniel Weizmann, Gene Aguilera, Clem Burke, Burton Cummings, Andrew Loog Oldham, Kim Fowley, Bill Mumy, Heather Harris and John Densmore.

Last century inside the Capitol Records studio B in Hollywood, Ca., Sir George Martin and I talked about a Frank Sinatra recording session he attended in this very same room on his first visit to Hollywood, in 1958. The EMI label sent him over the pond after Martin was invited by Capitol executive Voyle Gilmore to visit the American division.

Martin described that date when Sinatra was backed by Billy May’s orchestra while actress Lauren Bacall was in attendance. The songs cut were eventually placed on Sinatra’s Come Fly With Me LP.

I thanked George Martin for discovering and signing the Beatles to their British record label deal in the first place. And to praise his persistent determination, along with Brian Epstein’s, in encouraging Capitol Records to have some faith domestically in Martin’s groundbreaking Parlophone/EMI recordings with the band back in 1963.

Martin had heard an album I produced on the Doors’ Ray Manzarek, and personally sent me a letter, inviting me to his June 1999 Hollywood Bowl where he was conducting a repertoire of hand-picked Beatles’ tunes. I’ve framed his note. I had met all four members of the Beatles and interviewed three of them.

At my last studio encounter with George this century, I complimented Martin on his Cilla Black productions of two Lennon and McCartney songs, “It’s For You” and “Step Inside Love.” I’m sure it’s been a while since anyone touted these tracks to Martin.

Then, “While My Guitar Gently Weeps,” followed by “Eleanor Rigby,” from LOVE were played in Studio B. Try hearing the lad’s music over custom TAD monitors.

George autographed a solo album, put his arm around me and enthused, “Pretty good stuff. Don’t you think?”

I first heard “Love You To” from the Beatles’ Revolver LP in July 1966 previewed on radio station KRLA from Pasadena California during deejay Dave Hull’s shift.

He back announced the album selection and touted George Harrison’s vocal and sitar instrument on the Harrison-penned tune, along with referencing Ravi Shankar, the Indian classical musician.

The first week of August ‘66 I purchased my monaural copy of the album at the Frigate Record shop at the corner of Crescent Heights Blvd and 3rd Street in Los Angeles.

The Frigate was a mile from the 3rd Street World Pacific Studio where Shankar recorded in the sixties for Richard Bock’s World Pacific label, now part of Universal Music Enterprises.

In 1965, George Harrison initially discovered the sitar around the set of Help! Later that same year, he would record with it on John Lennon’s “Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown).”

In 1997, I conducted an interview with Harrison first published in HITS magazine. George recalled his earliest attempt at playing the sitar with the Beatles as “Very rudimentary. I didn’t know how to tune it properly, and it was a very cheap sitar to begin with. So ‘Norwegian Wood’ was very much an early experiment. By the time we recorded ‘Love You To,’ I had made some strides.”

Harrison further elaborated on his own sitar playing. “I’m not a very good one, I’m afraid. The sitar is an instrument I’ve loved for a long time. For three or four years I practiced on it every day. But it’s a very difficult instrument, and one that takes a toll on you physically. It even takes a year to just learn how to properly hold it. But I enjoyed playing it, even the punishing side of it, because it disciplined me so much, which was something I hadn’t really experienced to a great extent before.”

Harrison recollected about his initial meeting with Ravi Shankar in 1966 at a dinner party for the North London Asian Music Circle.

“His music was the reason I wanted to meet him,” continued George. “I liked it immediately, it intrigued me. I don’t know why I was so into it -- I heard it, I liked it, and I had a gut feeling that I would meet him. Eventually a man from the Asian Music Circle in London arranged a meeting between Ravi and myself. Our meeting has made all the difference in my life.”

As for the Beatles’ audio cosmic endeavors, Harrison suggested, “That was the environment in the band. Everybody was very open to bringing in new ideas. We were listening to all sorts of things, Stockhausen, avant-garde music, whatever, and most of it made its way onto our records.”

During September of 1966 Harrison travelled to Bombay and became a student of Shankar.

In 1997, I visited Ravi at his home in Encinitas, California and he described his relationship with George.

“He’s a very rare person. It is something so special. There are many other people who could do what George does, but they don’t have that depth. He’s so unusual. What has clicked between him and me, what he gets from me, and what I get from him, that love and that respect and understanding from music and everything, is really the most important thing. It’s not the money, or he helping me to record, that’s not the main thing. But it’s the very special bond between both of us.”

John Densmore: George Harrison came to one of our recording sessions for Soft Parade at Elektra studios. He said all the extra musicians on our session, ‘looked like one for Sergeant Pepper’s.

“[In 1967] Robby [Krieger] and I go see Ravi [Shankar] play at the Hollywood Bowl, and George is on stage. We had been students at his Kinnara School of Music. Ravi didn’t teach at the school, but he’d drop in and give a little lecture on Sublimating Your Sexual Drive Into Your Instrument.

“For some damn reason in 1965 Robby and I went to the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi’s Transcendental Meditation Center in Los Angeles on 3rd Street because LSD was legal and we were quite interested in our nervous systems, and knew we had to do this TM thing slowly.

“We go over there and I meet this little guy, Maharishi, and the ‘Love Vibe’ is very palpable. TM is the reason the Doors are together. TM glued together myself, Ray [Manzarek], Robby and Jim [Morrison].

“So maybe, 1966, 1967, I was noticing in the traditional Indian ragas you gotta wait for your climax. It’s not a quickie, you know, Sound wise, ‘The End’ was a raga tune. So that was the influence.

“Then, a year or two later, I read that the Beatles are onto TM and our little secret is being spread worldwide. Harrison was doing it in England. Great. The whole Eastern Indian thing, Ravi Shankar, via George Harrison and the Beatles, saturated everything. You hear the Indian thing in techno stuff now. That came in and it was deep and it’s still around. We need the East.”

Besides direction, technical guidance and the pioneering sonic production employed on Revolver by (Sir) George Martin, the hidden hero informing the sound of Revolver is engineer Geoff Emerick, who was the full-time recording and remix engineer under Martin. “Tomorrow Never Knows” was Emerick’s first session with the Beatles. Geoff was behind the console until midway through the recording of the Beatles’ White Album. He later returned to engineer Abbey Road. Emerick is, with Howard Massey, the author of Here, There and

Everywhere: My Life Recording the Music of the Beatles.

“I hear music in colors,” Geoff explained to me last decade inside Capitol Records’ Studio B. “Bass and drums are always my favorite,” he added. “And just building stuff around that, from color textures in my head upon what’s happening in the studio,” underlined Emerick.

Geoff’s drum and bass sounds have motivated generations of musicians. His recording techniques and innovations include automatic double-tracking; backwards guitar solo and loops, and real-time varispeed manipulation that infused John Lennon’s signature vocal echo.

Engineer Ken Scott, first started working with the Beatles at Abbey Road as a button pusher on June 1, 1964, during sessions for A Hard Day’s Night. The songs not utilized in the film like “I’ll Cry Instead” and “I’ll Be Back” as well as “Matchbox” and “Slow Down.”

Eventually Ken worked on Help! and Rubber Soul, before joining midway on Magical Mystery Tour, and halfway through the White Album recording.

In working with the Beatles, I got to experiment a lot and go through microphones and find out which mikes I liked for different things,” “So that moved on from there. Also, the learning experience with the Beatles is anything goes. It doesn’t matter if it’s a really bad sound as long as it fits.

“Ringo was a great drummer. Still so many people fail to realize that he was an incredible rock drummer. For me, it’s from his lack of technical knowledge. It was all feel for him. I’m of the opinion that he would go into a fill not knowing how he was ever going to get out of it. And halfway through he suddenly realized he has to get out of it, so come up with some unique way to get out of that fill

“EMI training was so amazing because they had such a long time to get it together. The reason they had you do mastering, and back then it was only called cutting, and they had you do mastering before engineering because vinyl has limitations. You can’t have too much bass on it. Otherwise, the record would jump. You can’t have things out of phase. Little things like that.

“Where with tape you can put anything on. So, they wanted you to learn the final product and the limitations of the final product before having the easy route of going onto tape. You get to learn those. The other thing you get to learn. And it was similar for all the engineers, when we first started to cut, to master, all we were doing were playback acetates. Those were seven inch 45 singles. They would only last for 10 or 12 plays.

“Don’t forget, this is before cassettes and certainly before CD’s. So, this was the way the artist, the producer, sometimes the arranger got to hear what they worked on. So, we’d have to cut those and they weren’t going out to the general public or anything like that. If you screwed up it didn’t matter. That’s why you started off on those. And we all did the same thing. The first time we were on our own we’d put a tape on and think, ‘It needs a little bit more of the high end.’ So, we’d go full bore adding high end. ‘Yeah…That’s better. And now we need some low end.’ We’d go full bore going low end. ‘Yeah…It’s close…We just need some mids now.’

“Every single album Norman Smith tried to make sounds different. He pushed the envelope as far as he could. It was very difficult to make radical changes when he was engineering. Each album got progressively more radical if you like. A change in microphone placements. Absolutely. And using different microphones.

“On the first album he wanted to capture them live in the studio. So, he set them up without baffles and without anything. It was as if they were on stage. That was the first album. Each one was different. To me, the way the Beatles got into experimentation a lot of that came from how they saw Norman changing things.

“Obviously they caught the ball and ran with it. Unlike anyone else at the time. But he was the one I think that first instilled in them ‘it doesn’t always have to be the same every album. You can change it sound wise.’ Obviously, there was musically their experimentation with other instruments. Norman was the first pop engineer to record sitar at Abbey Road. He was amazing. He was always pushing it.

“Abbey Road had their own pop shields for vocals. My belief is that they were especially made. I can’t tell you the pop shields around the microphones at Abbey Road made a huge difference, but it’s a combination. Everything starts in the studio. They were so good together vocally to start with and then that just made it so much easier for Norman to get it that much better.

Steven Van Zandt: It was extra notable by being the first album to have three George songs while we in America (as usual) lost three of the coolest tracks (‘I'm Only Sleeping,’ ‘And Your Bird Can Song,’ and ‘Dr. Robert’-the second coolest after ‘She Said She Said!’) as the American company continued to turn every two albums into three. Oh, and one more thing we should mention, they wouldn't decide to stop performing live until the next disastrous tour a few months later but they may have had a premonition at that point which undoubtedly opened their minds to even more adventurous artistic exploration.”

Clem Burke: As I sit here in my office listening to the Beatles’ album Revolver on my laptop while holding the vinyl in my hand. Yes it occurs to me that just by looking at the cover art you already knew the LP would be different, and it was! As much as Rubber Soul influenced everyone from Brian Wilson to the Byrds and on, Revolver was the real experimental leap forward for the Beatles. Here is where they really began singing about things other than love and girls. Songs like ‘Taxman,’ ‘Eleanor Rigby,’ and yes ‘Yellow Submarine’ were taking their inspiration from a very different place. Both lyrically and musically they were provocative, and who exactly was ‘Dr. Robert?’

“Having Ringo play along to a tape loop for ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’ was extremely inventive and unheard of at the time, not to forget the use of horns and strings and sound collage as well. This is the Beatles pop art album, from the multimedia cover to the eclectic points of reference in the sound and lyrics it is in my opinion the sound of things about to change not only in music but in the world as we knew it.”

Burton Cummings: You’ve got to remember that Revolver starts with George’s ‘Taxman.’ The album rocks hard. There were more ballads on Rubber Soul. We [Guess Who] did a television show 1966-1968 for the CBC [Canadian Broadcasting Company] Let’s Go. Sometimes we had to learn 12 covers in an adjacent radio studio that were then broadcast. We did ‘Got to Get You Into My Life.’ Later I sang ‘Yellow Submarine,’ complete with a megaphone. We later did ‘Hey Jude’ and some of our originals like ‘No Time.’”

Kim Fowley: In 1966 at the Ad Lib club, Paul McCartney was there, disguised and dressed as an Arab and walking around. I also met him at a party he politely crashed in St. John’s Wood down the street from him. Paul saw a bunch of cars parked and he dropped in to take a look, jumped back in his own car and split.

“Also in 1966, I spent some time with John and Paul in London. Bruce Johnston of the Beach Boys was in town doing advance publicity for the Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds and had an acetate pressing with him. I was asked to bring the Who’s Keith Moon over who brought John and Paul to the hotel room. They were both very impressed by the recording, left the hotel and went into the recording studio the next day and did ‘Here, There and Everywhere’ for Revolver. The both of them were able to digest and gauge the whole essence of Pet Sounds in one listening.

“George Martin was the catalyst for the embryonic dreams of Lennon, McCartney, Starkey and Harrison. Martin was able to consolidate and expand their anticipation. He was a great editor.

Andrew Loog Oldham: The last time I spent with Dennis Wilson, to utilize the phrase, I blew his mind out in a car. I had a little Phillips portable 45 RPM player in the back of my car. I played him a new Beatles 45 RPM. It might have been Sgt. Pepper, it might have been ‘Good Day Sunshine.’ It was the Beatles. It was 1966 and Dennis was late for his gig."

Bill Mumy: Revolver changed everything. Again. As the Beatles had been doing on a regular basis for a few years already. I bought the album for $2.83 from Ben who owned Do Re Mi Records on Pico Blvd in West L.A. I rode there on my purple Schwinn Stingray bike.

“The Klaus Voorman cover was stunning and led to hours of close inspection. The photo on the back of the Fab all wearing sunglasses was somewhat spooky yet full of positive vibes at the same time. Those DRUM SOUNDS! The punchy BASS SOUNDS. The swirling vocals and biting guitars... George Martin's arrangements and production... All FAB to the max.

“But it really boils down to the songs. And I can't think of another album in history that has better ones! To this day it shines as a brilliant project by the greatest and most magical band in the history of the universe! It is, in my opinion, quite probably the best album ever made.”

Heather Harris: Stories of the Beatles' ‘origins’ had osmosed to fans sufficiently by 1966 that most recognized the name Klaus Voorman when it appeared as the graphic artist responsible for the Revolver front cover. It seemed a nice gesture as well as nice design. What I've most appreciated was Voorman's persistence in the industry, eventually designing Scandinavian Leather for my faves Turbonegro in 2001.”

Ram Dass: I was really happy when Ravi Shankar started getting acceptance in the West, partly because of George Harrison going to India. I had heard of Ravi in the very early 60’s when I was in India. I played the tambora. I loved the Beatles’ music. I took acid to Sgt. Pepper.

“I loved the Doors. Some Eastern influences in their music. Jim Morrison was a poet. I liked the level of reality he played with. I like people pushing the edge and getting out of the linearity. I love that. And not in a kind of clever, studied way, but in an ecstatic experiential way. That’s what I love better. That’s what he tried to do. I met John Lennon and Yoko Ono. They came to my apartment in New York to meet me with the director, Peter Brook. John was very sweet, available and very curious and thoughtful. I found him a very loving being to be with.”

Roger Steffens: More than any other record of the time, Revolver was responsible for turning millions of people onto LSD.

“It was the book, The Psychedelic Experience: A Manual Based on the Tibetan Book of the Dead by authors Timothy Leary, Ralph Metzner and Richard Alpert (later Ram Dass), that had a profound influence on John Lennon and the Beatles’ composition, “Tomorrow Never Knows,” the first song recorded for the Revolver album.

“If you wondered what a trip would be like, all you had to do was put on earphones and close your eyes and wonderment abounded. Stunning new instruments inserted into the pop panorama; harpsichord and tablas and sitars and tapes spun backwards into a Delhi rave up. Prompting acidic reflections, feeling hung up but not knowing why, who cares as long as we can drift in this pill-shaped undersea craft and maybe find some of that Sunshine acid, John closing it all out in his submarine skipper voice. No doubt this is their finest most consistent and innovative work, a quantum leap forward.”

Rodney Bingenheimer: Revolver is my favorite album by the Beatles. ‘And Your Bird Can Sing’ is the track I love the most. It reminded me of the Byrds.”

Gene Aguilera: So maybe Eleanor Rigby is really my favorite Beatles song. McCartney ups the ante on the meaning of loneliness which takes me to the graveyard every time. Ray Charles’ version is just as good as the original, which is not an easy thing to do. ‘The Quiet Beatle’ George Harrison gets a bigger taste this time around--more vocals and more sitar. And when did the Beatles ever open up an LP with a George Harrison song? You can hear the Beatles maturing lyrically and musically on Revolver, setting the stage for Sgt. Pepper’s arrival the following year.”

Daniel Weizmann: I was born in '67 and pushed on the swings to Revolver--back then I thought their hair on the cover was spaghetti! But now it doesn't seem like a coincidence that Revolver has that black and white neo-realist album cover. The album--which starts with Taxes and ends with Eternity--faces adulthood head on, and plays like little b&w vignettes of Kitchen Sink drama.

“Death is ever-present here, from ‘Eleanor Rigbys’ lonely urban graveyard scene to the death-wish come-on in ‘Love You To’ to the final repudiation of death itself on ‘Tomorrow Never Knows.’ ‘Yellow Submarine’ is WW2 turned inside out, and ‘She Said She Said’ introduces a whole new kind of masculine wound--unbirth without even the knowledge of death. You're even advised to declare the pennies on your eyes before you hit the casket--yeah it's wit, but it's also the recognition of civilization's grave demands. Then there's the title of the album, a play on the LP and the pistol, an instrument of Life and an instrument of Death.

“The Beatles would always be great, of course, but for my money they struck a daring balance between Hard Truths of Reality and the Visionary Beauty of Soul here that they never topped.”

Harvey Kubernik is the author of 20 books, including 2009’s Canyon of Dreams: The Magic And The Music Of Laurel Canyon, 2014’s Turn Up The Radio! Rock, Pop and Roll in Los Angeles 1956-1972. During 2014, Otherworld Cottage Industries published Kubernik’s It Was Fifty Years Ago Today (The Beatles Invade America and Hollywood). Sterling/Barnes and Noble in 2018 published Harvey and Kenneth Kubernik’s The Story Of The Band: From Big Pink To The Last Waltz. In2021 they wrote Jimi Hendrix: Voodoo Child published by Sterling/Barnes and Noble.

Otherworld Cottage Industries in 2020 published Harvey’s Docs That Rock, Music That Matters, featuring interviews with D.A. Pennebaker, Chris Hegedus, Albert Maysles, Murray Lerner, Morgan Neville, David Leaf, Dick Clark, Curtis Hanson and Michael Lindsay-Hogg.

Kubernik’s writings are in several book anthologies: The Rolling Stone Book Of The Beats and Drinking With Bukowski. Harvey wrote the liner notes to the CD re-releases of Carole King’s Tapestry, The Essential Carole King, Allen Ginsberg’s Kaddish, Elvis Presley The ’68 Comeback Special, The Ramones’ End of the Century and Big Brother & the Holding Company Captured Live at The Monterey International Pop Festival.

In 2020, Harvey served as a consultant on the 2-part documentary Laurel Canyon: A Place in Time directed by Alison Ellwood that debuted on the M-G-M/EPIX television channel.

In November 2006, Kubernik was invited to address audiotape preservation and archiving at special hearings by The Library of Congress held in Hollywood, California.

During July, 2017, Harvey Kubernik was a guest speaker at The Rock & Roll Hall of Fame’s Library & Archives Author Series in Cleveland, Ohio discussing his 2017 book 1967 A Complete Rock Music History of the Summer of Love.