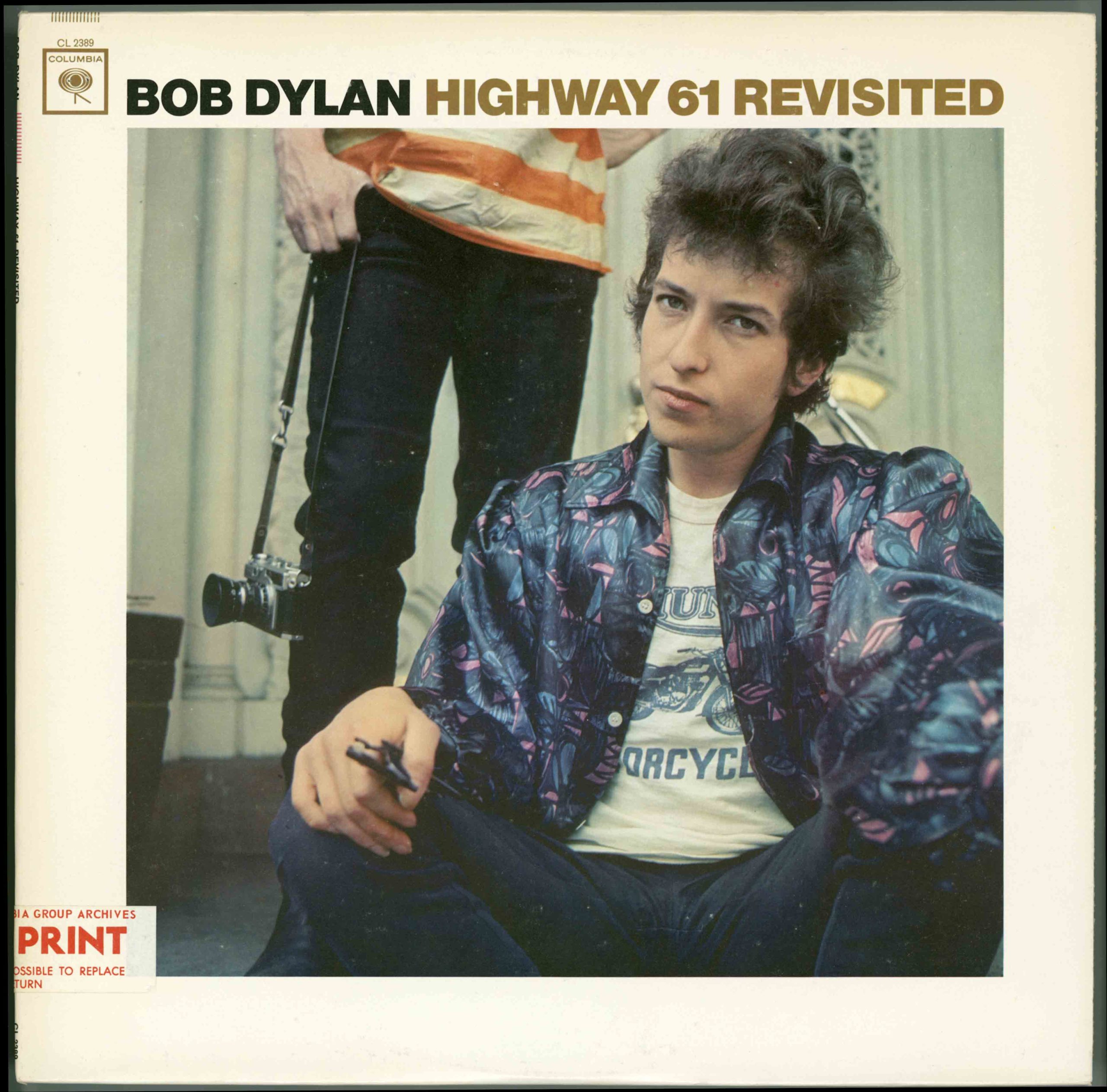

The June 16, 1965-August 4, 1965 Highway 61 Revisited album sessions of Bob Dylan were engineered by Roy Halee, Pete Dauria and Frank Laico at Columbia Records studio A in New York City. The musicians on the dates were Bob Dylan, Mike Bloomfield, Al Kooper, Paul Griffin, Charlie McCoy, Frank Owens, Russ Savakus, Harvey Brooks, Bobby Gregg, Bruce Langhorne and Sam Lay.

I purchased my mono copy of the LP at Wallichs Music City in Hollywood that September.

In 2001 and 2013 I interviewed Al Kooper about his 1965 recording endeavors with Bob Dylan. Multi-instrumentalist and songwriter Kooper worked with Dylan’s producers Tom Wilson and Bob Johnston on Highway 61 Revisited.

Kooper played organ on the Wilson production of “Like A Rolling Stone,” the first track cut for Highway 61 Revisited, plus additional selections with Johnston, who had replaced Wilson just after “Like A Rolling Stone” to complete the disc.

I heard that you stole Bob Dylan acetates out of Tom Wilson’s office.

I did. I was a bad boy. Tom was sort of a spectator sport producer. He didn’t do all that much. He’d put you in the studio and got the job done. He didn’t interfere in anything at least when I worked with him.

“Tom earlier worked for Savoy Records. Tom was a Harvard graduate. He was a very bright guy. He was a very high-class guy, a soulful and funny guy. But you knew he was bright and he talked about very erudite things.

“He really saved my life that day on that Dylan ‘Like A Rolling Stone’ session. Because, he could have…I went to him and said, ‘Man, let me play the organ.’ They had just moved Paul Griffin from the organ to the piano.

“And I went over to Tom Wilson, and I was invited just to watch, you know, and I said, ‘Man, why don’t you let me play the organ? I got a great part for this.’ Which was bullshit. I had nothing. And he said, ‘Man…You’re not an organ player…’ And then they came to him and said, ‘phone call for you Tom.’ And he just went and got the phone. And I went in to the studio and sat down at the organ. He didn’t say no. He just said I wasn’t an organ player. OK.

“On the Highway 61 Interactive CD released a few years ago, they have the multiple takes of ‘Like A Rolling Stone,’ and on there you can hear Tom Wilson, ‘OK. This is take 7. Hey! What are you doing in there?’ Then you hear me laughing, and that was the moment he could have just thrown me out and rightfully so. And you know what? He didn’t. And that was it. That was the beginning of my career. Right then and there. That studio dialogue is documented.

“Wilson is the guy who invited me to the session first of all, which is really nice. You didn’t get invited to Bob Dylan sessions, you know. Especially if you were a nobody like I was. And there it was. There was the chance he had to toss me, and it would have reflected back on him because he had invited me to the session.

Q: Tell me about the Columbia Records studio A where Highway 61 Revisited was done.

A: When I recorded with Dylan on Highway 61 it used to be on 799 7th Avenue. And that was Columbia Records and they had the studio in the same place as the offices. So when moved to Black Rock they then moved the studio further east. So it was on 49 E. 52nd

“They duplicated the studio on 7th Avenue. There were three studios there. 2nd, 3rd and 4th floor. And, so they could do a lot more sessions. And they had the same monitors and the same gear at every place. In those days they had rotary pots instead of faders that slid up and down. It was very archaic. It was also a union shop with required breaks every three hours. Across the US they had studios. So the worse part initially was, and if you were signed to Columbia, you couldn’t record at any outside studio.

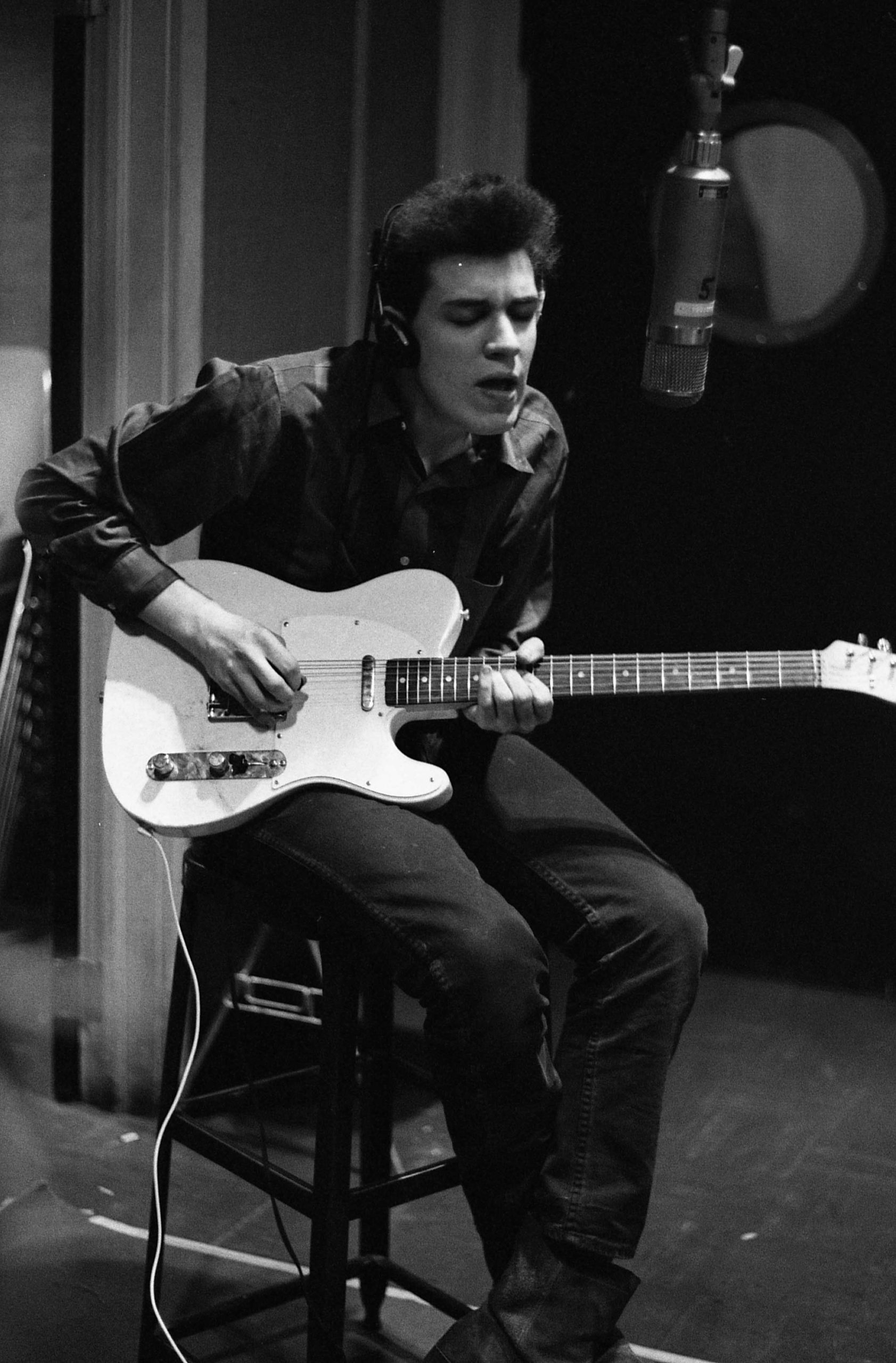

Q: Talk to me about guitarist Michael Bloomfield.

A: Well, Michael [Bloomfield] and I met on the ‘Like A Rolling Stone’ session. I had read about him in Sing Out Magazine, and saw a picture of him where he looked a little more rotund then he was when I met him. His brother says he was a fat kid growing up. So we met on the ‘Like A Rolling Stone’ session and really hit it off. So we played together on that.

“I was supposed to play guitar on that record. I packed up my guitar when I heard him warming up. It never occurred to me that somebody my age, and my religion could play the guitar like that. That was only reserved for other people. It never even occurred to me that that was an option for someone my age and my color. I had never seen that, or heard that up to that day.

“So, that pretty much ended my guitar playing by and large. I said, ‘well OK, he’s as old as me and he can play like that. I’m never gonna be able to play like that. Thank you, goodbye.’ And, you know, I ended up playing organ on that record, and then I became a keyboard player really that day. So, it was a damn good thing because, you know, that was competition I couldn’t deal with.

- And you brought bassist Harvey Brooks into the sessions as well.

- That’s right. I played the organ on ‘Like A Rolling Stone.’ Paul Griffin on piano was so brilliant. He plays amazing things. And the thing that is really eye-opening about it, are the drums. Bobby Gregg, who had a hit record with ‘The Jam.’ Besides Michael’s playing, you can really hear the drums of Bobby.

Q: On “Like A Rolling Stone” was there a specific reason why you played behind the runner on the track? The organ line follows Dylan’s vocal.

A: No. I did that because I was waiting to see what chord they were going to do. There was no music or lead sheet, or anything. I was just playing by ear and I didn’t want to be the one making a mistake because I was doin’ like a rebel run there.

Q: I think the secret sauce on the Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde On Blonde sessions was pianist/keyboardist Paul Griffin. He was on records by Garnet Mimms and on Chuck Jackson’s “Any Day Now.” Producer Tom Wilson first brought Griffin into the Dylan recording sessions. He was once married to Valerie Simpson, who sang on your epic Blood, Sweat & Tears’ Child Is Father To The Man album. Griffin was also a big influence on Steely Dan’s Donald Fagan.

A: Oh...man…A big influence on me as well! Paul came from the Baptist church. On Highway 61 Revisited we did the tracks to ‘Tombstone Blues’ and ‘Queen Jane Approximately’ in one day.

“The best thing I can say about Paul Griffin is take five minutes out of your busy day and get a time where you have nothing to bother you at all. Find a real nice stereo system and sit back and put on ‘One Of Us Must Know’ from Blonde on Blonde. And just listen to the piano…And tell me if you can find on a rock ‘n’ roll record anybody playing better than that. And I would really like to hear what your decision is. To me it is the greatest piano achievement in the history of rock ‘n’ roll.

“I don’t hear anything than him playing the piano when I hear that record. And I’m thrilled that I’m playing organ but I’m embarrassed. And I think that Dylan should be embarrassed, too. ‘Cause Paul just steals that fuckin’ record. It’s the most incredible piano playing I’ve heard in my life. If you’re a piano player try playing that note for note. It’s just incredible.

Q: What is so unique about Bob Dylan’s own piano playing?

A: No one talks about his piano playing because they don’t know. Bob had a very unusual way of playing in that he didn’t use his pinkies. So both his pinkies were up in the air when he played the piano and very interesting to me. It was very interesting looking to watch that. I used to really kick a kick of that.

Q: In 1965 and ’66 did you realize you were recording on some monumental songs with a long shelf life? Did you know Dylan’s material would make impact and travel into another century?

A: I learned it after I did Highway 61 Revisited. So that one time during Blonde On Blonde I started thinking, ‘you know, where ever my hands moves next it’s gonna be around for all time.’ I started thinking like that and I said to myself ‘will you please shut up and just do what you do.’ It can completely freak you out if you thought like that. And I had that thought for one second, and then I said, ‘I really can’t think like this and do this job.’ So, yeah, but not on Highway 61 Revisited, but on Blonde On Blonde I did have that thought.”

Record producer Tom Wilson once described Bob Dylan in the recording studio, “He becomes a white Ray Charles.”

I suggest listening to Charles’ 1959 recording “I Believe to My Soul,” which has more than a passing musical arrangement influence on Dylan’s “Ballad of a Thin Man,” heard on Highway 61 Revisited.

Also apparent is the melodic framework of the Smokey Robinson-penned “My Girl,” a number one hit record by the Temptations in early 1965 that informs Dylan’s “Queen Jane Approximately.”

I mentioned my theory to Al Kooper, who during his career has recorded three Smokey Robinson tunes.

Al enthusiastically replied, “One of my favorite things is when I called (Bob) Dylan one day and said, ‘Hey…What are you doing?’ ‘Eating a piece of toast and listening to Smokey Robinson...’ So, that makes a lot of sense.”

Dr. James Cushing formerly with the English and Literature department at Cal Poly San Luis Obispo once hosted a weekly Bob Dylan’s Lunch radio program broadcast on KCPR-FM.

Earlier this century Cushing and I discussed Highway 61 Revisited.

“Has anyone made much of the specific role of the double-keyboard sound on Highway 61 Revisited? The piano and organ, together? That's unusual in pop but not in gospel. I've had a feeling for decades that this LP has an implicit gospel feel that adds to the surrealism of the songs while emphasizing the element of prophetic moral judgment in their lyrics (the Highway 61 Revisited songs either pass strong judgment on characters or describe chaotic scenarios or both).

“Al Kooper did a gospel number on Projections, the Blues Project's only studio LP, so he knew all about that genre... To say nothing of the ‘God said to Abraham’ opening of the title track.”

“Dylan takes the idea of modern poetry, which is that the poem is a dramatic monologue, spoken by a character and whatever the character is talking about the character is also describing his own interior state of mind. Which includes his analysis of society. That’s what Walt Whitman is doing. That’s what T.S. Elliot is doing. That’s what Ezra Pound is doing. And that’s what Bob Dylan does.

“In 1965 and 1966, as a young teenager, I remember thinking, as Highway 61 Revisited played on my Dynavox, ‘I will be listening to this album the rest of my life.’ It was possibly my first adult moment.”

In 1975 I interviewed Johnny Cash for the now defunct Melody Maker, and during our conversation, he cited Bob Dylan.

"I became aware of Bob Dylan when the Freewheelin’ album came out in 1963. I thought he was one of the best country singers I had ever heard. I always felt a lot in common with him. I knew a lot about him before we had ever met. I knew he had heard and listened to country music. I heard a lot of inflections from country artists I was familiar with.

“I was in Las Vegas in '63 and '64 and wrote him a letter telling him how much I liked his work. I got a letter back and we developed a correspondence."

A year later Cash and Dylan connected.

"We finally met at Newport in 1965. It was like we were two old friends. There was none of this standing back, trying to figure each other out. He's unique and original.

“I keep lookin' around as we pass the middle of the 70s and I don't see anybody come close to Bob Dylan. I respect him. Dylan is a few years younger than I am but we share a bond that hasn't diminished. I get inspiration from him."

Bob Johnston is the record producer of Johnny Cash’s Folsom Prison and San Quentin live LP’s, Simon & Garfunkel’s Bookends, the first few albums of Leonard Cohen and sessions with Moby Grape.

John produced Dylan’s Highway 61 Revisited, Blonde On Blonde, Nashville Skyline, Self Portrait New Morning and John Wesley Harding.

I interviewed Bob Johnston this century. He died of heart failure at the age of 83 in Gallatin, Texas on August 14, 2015.

Bob was born in Hillsboro, Texas. For a short period he held a staff writing job at Elvis Presley’s Hill & Range Music, before securing talent for the Kapp company and arranging for Randy Wood’s Dot Record label, before joining Columbia Records in 1965 as a staff producer.

Johnston first met Bob Dylan in ‘65 when he was called in to replace producer Tom Wilson to complete Dylan’s Highway 61 Revisited album in New York City. This was after Wilson produced the “Like A Rolling Stone” session date.

“I was working with Dylan in New York and I flew in Charlie McCoy from Nashville, introduced him to Dylan, and the first thing we cut was a version of ‘Desolation Row,’ with Dylan on acoustic, Charlie on electric, and Harvey Brooks on bass,” recalled Johnston.

“Dylan and I were notorious for using first takes,” Bob revealed. “I don’t see any sense in doing it over and over. They knew what I wanted them to play not what I gave them. That’s why they were there. When I started with Dylan he said, ‘my voice is too loud.’ Good enough. So I turned it down. Then I’d turn it up. ‘Man, I can’t hear myself’ and had that voice out there. Finally we got to the place where he said ‘I can’t hear myself.’ ‘Cause I’d brought it so low. So I told him I’d take care of it and never asked him about it anymore and turned everything up and had that voice out there.

“I would place glass around Dylan for recording,” explained Johnston. “He had a different vocal sound. I didn’t make his different vocal sound. He always had different sounds on. I never wanted to be [Phil] Spector.

“I always had 4 or 8 speakers all over the room and I had ‘em going. The louder I played it the better it sounded to me. This is the way I really did it. As a songwriter, I wrote songs, too. Dylan changed the world. Every song he did I loved. I was a Dylan freak and I knew he was changing the world. I knew he was changing the society as we know it.

“I’ll tell you something else I did with Dylan, and recording Dylan and Cash,” he continued.

“Everybody else (at the time) was using one microphone. Which means you have to sacrifice something. If you’re gonna have a band you can’t have the band playin’ full tilt, if you’ve got him in the middle because and can’t understand everything with different people in there raising the guitar up, raise the drum up, and do shit like that.

“And what I always did was that I had three microphones because he was always jerking his head around, and I put the microphone on the left, center and right and it didn’t matter where in the fuckin’ room he went. And then I’d mix and start on the left and go all the way over on the right. So I’d usually have the piano on the outside left, without any echo. And then I’d put the echo on the right side. And then I’d have one of the guitars on the right and put the echo on the left. And then I’d match it all alone and brought up everything even so they could fight it out. And then that’s the way the band was.

“They didn’t have to raise this and lower this, and 15 people sitting around doin’ all that shit. The band was there and he was full tilt. Then you could go any place in the room and understand him. And I never heard another word from him about anything.

“What I did was put a bunch of microphones all over the room and up on the ceiling. I would use all those echo when everything got through and I could do that as much as I wanted. I wanted it to sound better than anything else sounded ever, and I wanted it to be where everybody could hear it.”

Fred Catero was a Columbia Records studio staff engineer from 1962-1972. He engineered Dylan’s demo session for producer John Hammond in 1962.

During his tenure at the Columbia studios, Catero was behind the board with Mel Torme, Aretha Franklin, Barbra Streisand, producer John Simon and Tom Wilson on a Herbie Mann album.

“I knew concepts of chamber recording. We used Neumann microphones,” Catero stressed to me in a 2014 interview.

“Columbia studios had JBL speakers. The Columbia studios had great echo. And you wanted that. In fact, it added to the drama. Also I knew the rooms and where the best place was for piano or bass or the singer.

“I did some work with Bob Johnston at Columbia. He was blasting the music so loud and saying, ‘turn it up!’ And I got to the point where I said, ‘here’s the volume button. Close the door when I leave the studio control room. Turn it up as loud as you want. But wait ‘till I get outside since I have to make my living with my ears. I can’t risk it.’

“I remember him saying once, ‘Damn it! If I don’t feel it in my chest I can’t tell if I have it. It’s there.’ He used the actual pressure to his chest on his body and was able to analyze.”

“Every generation falls in love with itself - their fashion, their politics (or lack thereof), their drugs, their movies - but nothing defines its sense and sensibility like their music,” declares author Kenneth Kubernik.

“And, like the ‘never ending tour,’ the never-ending debate over which decade can lay claim to having the hippest sounds marches on like a May Day parade, lockstep, impervious to reason, impassioned and ultimately irreconcilable. But I'll be goddamned if anyone is ever going to convince me that was or will ever be a more transcendent moment in music than the whip crack downbeat introducing ‘Like A Rolling Stone’ to a cohort of anxious ears fine-tuned to their AM radios in the summer of '65.

“I can still recall hearing for the first time that, yes, ‘jangly rhythm,’ Paul Griffin's strutting octaves, Al Kooper's eruptive organ, all keenly pitched to Dylan's anthemic wail. Chilling, absolutely chilling. Like a blast of rolling thunder, ‘Like A Rolling Stone’ not only signaled a change in Dylan's direction, it revivified pop music, forcing artists to reexamine the possibilities afforded them creatively, commercially and most importantly, critically.

“Yes, the rock music critic is born in the wake of Dylan conferring upon the form a level of rigor, musically and lyrically, that elevates the appetites of teen-age America from mere consumers to denizens of a new world order.

“If that sounds a trifle grandiose, then you weren't there, you didn't feel the crackle of excitement, the sudden awareness that the song emanating from you little Philco transistor was as transformative as Beethoven's Ninth Symphony, as Ornette Coleman's residency at the Five Spot. The albums that followed, Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde On Blonde confirmed the scope of Dylan's impudence.

“Fifty six years later we're still reeling (and rockin') from that annus mirabilis- '65/'66. Let's see how the current generation's music fares half a century hence.”

“What Bob Dylan did for me, everybody and our generation it will never have to be done again,” Jackson Browne explained to me in a 2021 interview we conducted for Music Connection magazine.

“The way he opened up our thinking and our feeling and our view of the world only has to be done once. Maybe it’s done in other fields like film and painting and other art. As a people we’re constantly growing, expanding but the changes that Bob Dylan brought to rock ‘n’ roll and songwriting are permanent. They’re part of us. People who are just being born into it now are being born into a world that wasn’t that way until Bob Dylan made it that way. It’s a particular skill to write something in a few words that speaks volumes. It is very difficult to say how I feel and how I think about Bob Dylan in a few words.”

Harvey Kubernik is the author of 20 books, including Leonard Cohen: Everybody Knows, Neil Young: Heart of Gold, Canyon Of Dreams: The Magic And The Music Of Laurel Canyon, 1967 Summer of Love, and Turn Up The Radio! Rock, Pop and Roll In Los Angeles 1956-1972.

Sterling/Barnes and Noble in 2018 published Harvey and Kenneth Kubernik’s The Story Of The Band: From Big Pink To The Last Waltz. For October 2021 publication the duo wrote Jimi Hendrix: Voodoo Child for Sterling/Barnes and Noble.

Otherworld Cottage Industries in 2020 published Harvey’s book, Docs That Rock, Music That Matters, featuring interviews with D.A. Pennebaker, Chris Hegedus, Albert Maysles, Murray Lerner, Morgan Neville, Dr. James Cushing, Curtis Hanson, Michael Lindsay-Hogg, Andrew Loog Oldham, Dick Clark, Ray Manzarek, John Densmore, Robby Krieger, Travis Pike, Allan Arkush, and David Leaf, among others.

Kubernik’s writings are in several book anthologies, including The Rolling Stone Book Of The Beats, Drinking With Bukowski and The Bob Dylan Electric Omnibus Volume 1.

This century Harvey wrote the liner note booklets to the CD re-releases of Carole King’s Tapestry, Allen Ginsberg’s Kaddish, Elvis Presley The ’68 Comeback Special and The Ramones’ End of the Century. During 2020 Harvey Kubernik served as Consultant on the 2-part documentary Laurel Canyon: A Place in Time directed by Alison Ellwood. Film’s debut broadcast was on EPIX television.