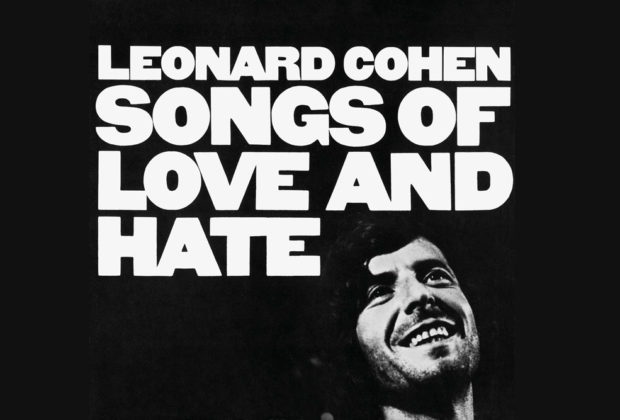

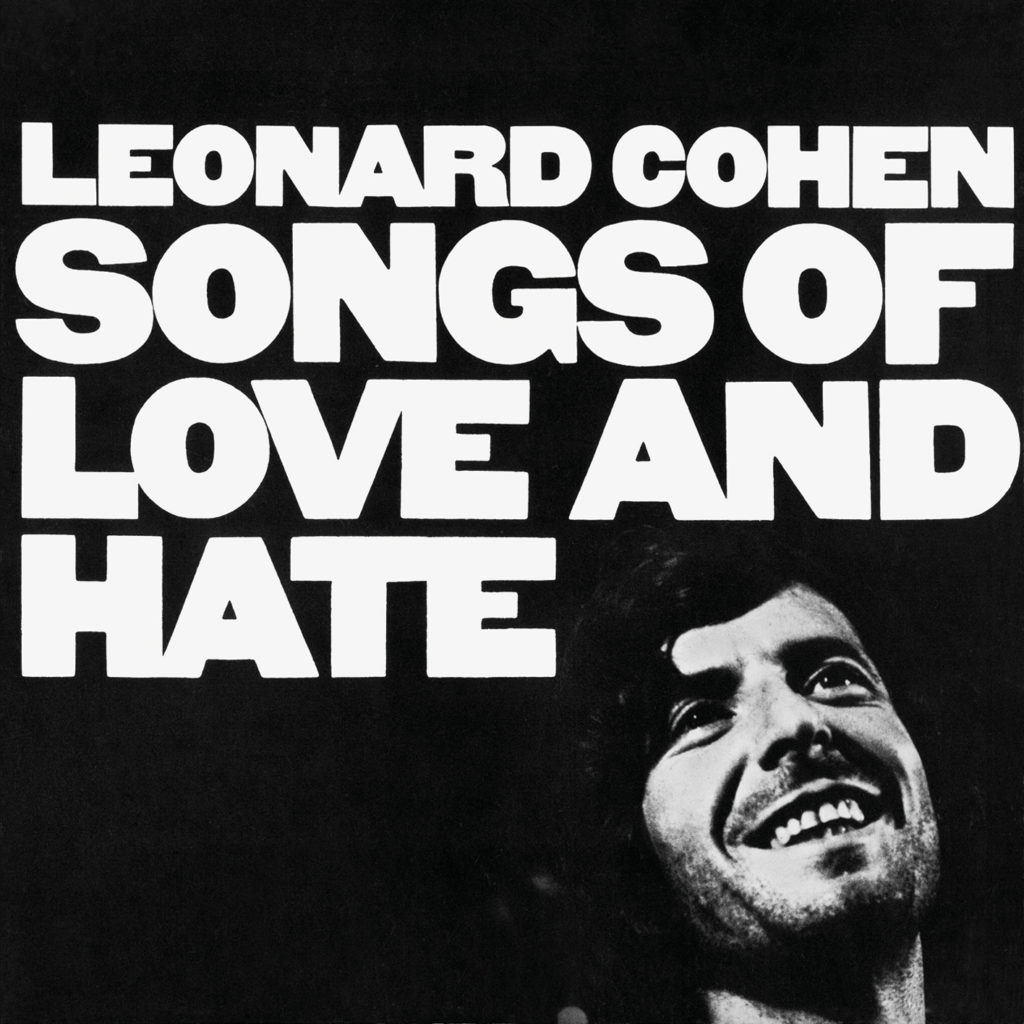

Singer-songwriter and poet Leonard Cohen’s third studio album Songs of Love and Hate produced by Bob Johnston was released by Columbia Records (now Sony Music) on March 19, 1971.

Johnston’s sparse production displays Cohen’s voice and guitar guiding his stories augmented by a slew of top notch musicians including Charlie Daniels, Ron Cornelius, Elkin “Bubba” Fowler and vocalists Corlynn Hanney and Susan Mussmano. Paul Buckmaster supplied the string and horn arrangements.

The 2007 retail CD reissue includes outtake of “Dress Rehearsal Rag” from his 1968 LP Songs From a Room along with several Cohen fan favorites “Joan of Arc,” “Dress Rehearsal Rag,” “Avalanche,” and “Famous Blue Raincoat” along with a live performance of “Sing Another Song, Boys” culled from his appearance in August 1970 at the Isle of Wight Festival in England.

Judy Collins in 1966 recorded “Dress Rehearsal Rag” on her LP In My Life, Nick Cave & the Bad Seeds cut “Avalanche” on their From Her to Eternity 1984 album, while “Famous Blue Raincoat” was covered by Jennifer Warnes in 1987 on her tribute to Cohen, Famous Blue Raincoat.

Canadian-based author Michael Posner in December 2020 wrote a definitive biography of Leonard Cohen, Untold Stories published by Simon and Schuster in December 2016, which is the first of three volumes.

I asked Posner about Cohen’s Songs of Love and Hate.

“Songs of Love and Hate is Cohen at his darkest. Most of the tracks reflect the desperate situation he found himself in, professionally and personally. His fractious relationship with Suzanne Elrod, his contempt for the very fame and status he had once aggressively pursued — it’s all on display here. The first words on the album tell us he has stepped into an avalanche that covered up his very soul (“Avalanche”).

“In ‘Dress Rehearsal Rag,’ he even contemplates suicide. , The disappointment of the Elrod relationship —less than two years old when the song was written— is front and center in ‘Diamonds in the Mine...’

“Although Cohen never spares himself in these critiques, five of the eight songs on the album are meditations on brokenness and a sixth, ‘Famous Blue Raincoat,’ is a reflection on his betrayal by a former lover, Marianne Ihlen, and a male friend.

“More than other any other album, it is the songs of love and hate that cemented Cohen’s reputation as the grocer of despair.”

Were there ever a poet, novelist, singer-songwriter, recording artist, global arena/stadium-filling tour attraction, icon and inspirational alta cocker like Leonard Cohen?

From his novels, The Favourite Game and Beautiful Losers, to timeless songs such as “Suzanne,” “Dance Me to the End of Love,” and “Hallelujah,” Cohen is a cherished artist. His physical passing in 2016 is still acknowledged and celebrated by friends, fans, journalists, authors and filmmakers.

I was an acquaintance of Leonard Cohen for 40 years.

In the mid and late seventies I conducted a series of interviews with Leonard for Melody Maker at his two different Southern California residences, was present on many of his Phil Spector-produced Death of a Ladies’ Man recording sessions at Gold Star and MCA/Whitney studios, handclapped on a couple songs, visited him during engineer/producer Henry Lewy sessions, mixes and playbacks at Kitchen Sync Studios, and noshed with Cohen at local Hollywood haunts a handful of times during this century.

In 2015 I wrote and assembled a hardcover coffee table size volume Leonard Cohen: Everybody Knows for Palazzo Editions currently published in six foreign languages. In 2016, the title was published in Chinese and Russian.

My multi-voice narrative memoir tribute to Cohen can be read at leonardcohenforum.com.

In the March 1, 1975 issue of Melody Maker, the now defunct English music weekly, I discussed touring, music and his literary influences with Leonard one afternoon at the Continental Hyatt House in Hollywood, which followed his Troubadour Club engagement.

“My music now is much more highly refined. When you are again in touch with yourself and you feel a certain sense of health, you feel somehow that the prison bars are lifted, and you start hearing new possibilities in your work.

"I don't have any reservations about anything I do. I always played music. When I was 17, I was in a country music group called the Buckskin Boys. Writing came later, after music. I put my guitar away for a few years, but I always made up songs. I never wanted my work to get too far away from music,” underscored Cohen.

"In the early days I was trained as a poet by reading English poets like Lorca and Brecht, and by the invigorating exchange between other writers in Montreal at the time.

"My tunes often deal with a moral crisis. I often feel myself a part of such a crisis and try to relate it in song. As far as the use of Biblical characters in such tunes as 'Story Of Isaac,' and 'Joan Of Arc.' it was not a matter of choice. These are the books that were placed in my hand when I was developing my literary tastes."

In August 1970 Leonard Cohen was booked at the Isle of Wight festival in England. A full performance of this translucent recital is out on DVD directed by Murray Lerner.

“I first heard Cohen as a literary character, a poet,” Lerner reflected in a 2010 interview I conducted with the Oscar-winning filmmaker. “He came out acoustic and walked out with guitar with his band called the Army.

“To put music to poetry was like hypnotic to me. And I was always thinking, in relationship to the performers, ‘What’s my role in what they are singing about? How do I fit into that?’ I change with each one as I am watching them. Like with the Moody Blues, I liked their music. It was different and interesting, and like Leonard Cohen, it had an undercurrent of mysticism to it.

“I thought the Isle of Wight1970 and the Cohen footage had touched the deep chord of people. I realized how deep it was and I was startled how prophetic it was. I was proud and excited at what I had done.”

Following his appearance at Isle of Wight, Cohen took the Army, back to Nashville and producer Bob Johnston to record his third album, Songs of Love and Hate.

"I used to be petrified with the idea of going on the road and presenting my work,” Leonard confessed to me in our first Melody Maker encounter.

“I often felt that the risks of humiliation were too wide. But with the help of my last producer, Bob Johnston, I gained the self-confidence I felt was necessary. My music now is much more highly refined.

"I liked the work he did with Dylan and we became good friends. Without his support I don't think I'd ever gain the courage to go and perform. He played harmonica, guitar and organ on tours with me. He's a great friend and a great support. We worked hard on the albums we did together but I wasn’t totally happy. Overall, I couldn’t find the tone I wanted. There were some nice things, though.”

It was Cohen’s long-cherished dream to record in Nashville Tennessee.

Bob Johnston was now running Columbia’s Nashville operation. His career began as a songwriter. Eventually he held a staff writing position at Elvis Presley’s Hill & Range Music, often reviewing potential Presley demos and songs earmarked for Presley movies in 1964 and 1965.

Johnston had peripatetic stints talent scouting for Kapp Records and arranging for the legendary Dot Records label. Arthur Alexander did one of Johnston’s songs and so did Mac Curtis, before Johnston joined Columbia Records in 1965. That year he produced Patti Page’s top 10 hit single “Hush, Hush Sweet Charlotte.”

From 1965-1969 he produced a string of influential Bob Dylan albums: Highway 61 Revisited, Blonde on Blonde, John Wesley Harding and Nashville Skyline.

“I put Cohen’s 1970 band together for him and told him I’d get him the best musicians in the world,” enthused Johnston in a 2007 interview we did. “And he said, ‘Bob. I don’t want the best musicians in the world. I want friends of yours.’ I said, ‘Good enough.’

“When Leonard first came to town he was in an old person’s hotel and stayed about the first week. And then me and [songwriter] Joy [Byers], my wife, leased acres from Boudleaux Bryant and his people and it was a little house by a creek. And then Leonard looked at this house and went all through it, and saw the 1,500 acres, and he said, ‘One day I’ll have a house like that and I’ll be able to stay and write when I want to write.’ And I replied, ‘Why don’t you just begin now?’ And I gave him the key and he moved in.

“I’ll tell you something else I did recording Dylan, and Cohen. I put them in the studio booth surrounded by glass and air where it used to be wood. Now everybody else could walk around and see them and talk to them. And that’s the way that it was. You can’t record in a room, not see the people, and not know what the other guy is gonna play.

“Everybody else was using one microphone,” delineates Johnston. “What I did was put a bunch of microphones all over the room and up on the ceiling. I would use all that echo as much as I wanted.

“I wanted it to sound better than anything else sounded ever, and I wanted it to be where everybody could hear it. I always had four or eight speakers all over the room. I had the engineer Neil Wilburn—did the Cash Folsom Prison live album with him. And he was a genius behind all that shit. I had a great thing with anybody who was a genius.

“I put together the studio band for Leonard. I hired all those guys who were doing the demos from the South. Charlie McCoy [harmonica and guitar], Charlie Daniels [bass, fiddle, acoustic guitar] who I knew from 1959, Ron Cornelius [acoustic and electric guitar], Elkin “Bubba” Fowler [bass, banjo, acoustic guitar]—and I played keyboards. I did a record with Ron Cornelius’s group [West] in 1967.

“Leonard and I walked into Columbia Studio A. It had a bench there, a little stool. He said, ‘I want to play my song.’ And I said, ‘We’re going to get some hamburgers and beer.’ And he said, ‘I want to play my song.’ I said, ‘Go ahead and play it and turn the button on there.’ ‘No. I want you around.’ And I said, ‘I want to get some beer.’

“So we walked over across the street to Crystal Burgers, he came, had a couple of hamburgers and beer and came back. ‘What do you want me to do now?’ he asked. I replied, ‘Why don’t you get your guitar and tune it?’ And he looked at me, so I had his guitar tuned, and he got on the stool. And I said, ‘Play anything you want to.’ ‘OK.’ ‘Roll tape.’ And Leonard played the song ‘The Partisan.’ And he got through it and asked to hear it. ‘Yeah.’ Played it back to him. He looked at me and said, ‘God damn. Is that what I’m supposed to sound like?’ And I said, ‘Forever.’ And there it was,” reminisced Bob.

“I always ask the artist ‘What do you want to do?’ You get better performances when you make the artist comfortable. Dylan, Cash, Cohen were just wonderful people and they should be treated as such.

“What attracted me to Cohen and songs like ‘Bird On The Wire’? What attracts you to Leonardo da Vinci? Leonard was the best I’d ever heard. And Dylan was the best I’d ever heard. And [Paul] Simon was the best I’d ever heard. And Cash was the best I’d ever heard. And all those fuckin’ people were the best I’d ever heard.”

Charles E. Daniels was born October 28, 1936 in Wilmington, North Carolina. In 1953 he performed in a bluegrass band, the Misty Mountain Boys, with childhood friend, Russell Palmer, and wrote his first song. By 1958 he began his professional music career performing with The Rockets.

At the age of 23, as a professional musician, with the instrumental rock & roll combo, the Jaguars, the group (1959-1967) landed a recording session for Epic Records with Bob Johnston, Daniels then co-wrote “It Hurts Me” with Johnston which was recorded by Elvis Presley and put on the flip side of “Kissin Cousins.”

Bob Johnston invited Daniels to Nashville. Multi-instrumentalist Daniels played on Dylan’s Nashville Skyline, and with Marty Robbins.

In 2017 I interviewed Daniels discussing Johnston, Dylan and Cohen,

“Dylan recorded in Nashville in 1966 for a while, but it was he’d come to town, do his stuff, and leave. Dylan happened to record in a studio in Nashville and worked in it. Forget that when Leonard came to Nashville. He lived out in the country for a while.

“Leonard came to Nashville in September of 1968, and lived locally in a cabin. I actually picked up Leonard Cohen at the airport when he arrived in Nashville with his friend Henry [Zemel] from Montreal. Johnston was booked in a studio. I had long hair and a mustache. I didn’t know who Leonard Cohen was. I knew he was a recording artist and comin’ to town and that we were gonna do some sessions with him. I didn’t know what he did. I knew he had a song called ‘Suzanne,” remembered Charlie.

“You don’t know what to expect when you go to meet somebody for the first time who is a totally different kind of musician than anyone you’ve ever been exposed to. You don’t know what kind of personality they have or what they’re gonna be like. But it was a very pleasant surprise that Leonard Cohen was as down to earth and nice as he could be. He spoke a different way than everybody else around there did. But he had a great sense of communicating with people.

“I will never forget that when Leonard came to Nashville he lived out in the country for a while. And there was a guy who lived out there, an old cowboy called Kid Marley. I mean, people who came from totally opposite end of the spectrum. It was Leonard Cohen and Kid Marley. But they just hit it off and got to be friends. Leonard was just that kind of guy.”

“One thing that needs to be said about Bob Johnston and bringing people to town like Dylan and Leonard Cohen. There was skepticism about Bob coming to Nashville because he was taking the place of a legendary producer, Don Law, who was an institution in town. Here’s this guy Johnston from New York, who had been doing Simon and Garfunkel, Dylan, and now Leonard Cohen, who were not really thought of as being country. But the first thing Bob did was a number-one song with Marty Robbins! He had gained credibility.

“And in ‘67 and ’68 Bob produced the albums John Wesley Harding and Johnny Cash at Folsom Prison. Bob had gained credibility. He was also at the same time, bringing Dylan and Leonard Cohen into town who had never lived here.

“And, hassles with long hairs, prejudice, racism, didn’t exist in our world. In the sixties everything was pretty much in the throes of a lot of upheaval. This was back in Martin Luther King, Jr.’s salad days, when he was going around, doing things that a lot of people didn’t understand it or didn’t get it. I was in Nashville when Dr. King was assassinated in Memphis. The thing was, when you’re goin’ in to make music that is a whole other thing.

“Nobody wanted to work in the big [Columbia] studio until Bob Johnston came to town and basically took it over. Nobody else wanted to be there. He worked with it, got engineers he enjoyed working with like Neil Wilburn, and he actually brought an engineer from New York with him when he first came down.

“The Columbia Studio was union. In Nashville, in the studios, you had to have the machines to be a certain distance away from the boards so the engineer could not work them both. But the thing I remember mostly about Studio A., the big studio, it was the new studio. The old studio, the Kwansit Hut, was the legendary studio where the hits had been cut. Everybody wanted to work in that room.

“I did learn from working with Johnston and Cohen that ‘less is more.’ I came out of the nightclubs, 13 years of beating my brains out playing every kind of music you could think of. You played the hits of Marty Robbins, Stonewall Jackson and Little Richard. So I played a variety of music. Most of it was bang, slap, get it going, turn it up loud and let it rock. And to go play music with a guy like Leonard Cohen, whose music was so fragile, you just stayed out of his way. That was basically what you wanted to do.

“The best way I know to describe it is that you listen to Leonard and his guitar. Wherever he was, wherever there was a part that you’d think you would do would interfere with you just stayed out of it. You didn’t try to embellish what he was doing. You didn’t try to guide what he was doing. You just tried to fit in. And there was whole mind set to that. And after I got used to the mindset it went really well. That was the approach to it. It was relaxed.

“With people like Cohen and Dylan…Most of the Nashville sessions, the country artists they would bring a demo in, they’d play the demo, you play it like the demo, you may change a key on it, but basically it’s gonna be the same thing, how they want the demo. So you’re playin’ pretty much inbounds.

“Leonard Cohen and Bob Dylan were singers and songwriters. They write their songs, and they weren’t coming in from a music publishing company. It was a lot different because there is no hurry.

“Now Leonard Cohen tuned his gut-string guitar down a full step and how he played it I could never figure out. I mean, in my world I couldn’t do it. No way. That’s impossible. My touch has never been that soft. And to have a touch that soft … That was the thing about his music, though. It was so fragile. It was so ‘Stay out of the way.’ Must have done ten songs, including ‘The Partisan,’ five or six were on Songs from a Room, and another on his Songs of Love and Hate.”

“I grew up with classical music,” Bob Johnston informed me. “I wanted the sound to be classical and I wanted it to be pop, too. I then went to England with Leonard and brought him to Paul Buckmaster.”

Buckmaster had been on scholarship to the Royal Academy of Music (London); graduated in 1967. He then toured Germany as a cellist with the Bee Gees’ backing orchestra. Paul’s arranger and conductor credits since 1969 were most impressive: he wrote the musical score and string parts for David Bowie's "Space Oddity" and arranged and conducted Elton John’s eponymous debut album, and Tumbleweed Connection.

“In 1970, I received a phone call from Bob Johnston that Leonard Cohen was coming to London to record, and would I like to write arrangements,” Buckmaster recollected to me in a 2017 interview.

“Bob was very affable and I immediately took a liking to him; he asked me to write arrangements for Leonard's album, then under production.

“Of course I knew who Leonard was and had listened to his records; was aware of ‘Suzanne.’ Was very attracted to his style, and liked his sort of understated somber darkly romantic vocal style and accompaniments, and much liked the lack of histrionics.

“Upon meeting Bob, he turned out to be an even a nicer guy. Bob and Leonard came over to my place in Fulham (London), where I lived with my wife, the pianist Diana Lewis, who had played Moog modular synthesizer on the tracks ‘The Cage’ and ‘My First Episode at Hienton,’ from Elton John. One guy from Texas and one from Canada; I believe this was the first time working with Americans!

“Leonard is a quiet guy; as I met him in '70, darkly handsome, with a frank, penetrating but not intimidating gaze. I felt the same kind of presence that one feels from his records; what you hear on his records is what he is in real life. We listened to and discussed the songs Bob and Leonard wanted me to write for; I got working, followed by the recording sessions.

“Bob gave me a quarter-inch stereo tape of the basic tracks (vocal and guitar) to which I listened while writing the arrangements head-to-paper. Did not add any strings, etc., on the tracks with rhythm section; only the vocal-guitar ones.

“The tracks I arranged are ‘Avalanche,’ ‘Last Year¹s Man,’ ‘Dress Rehearsal Rag,’ ‘Love Calls You By Your Name,’ ‘Joan of Arc,’ and ‘Famous Blue Raincoat.’”

I asked Paul about Trident Studios where he worked with Elton John and Leonard Cohen.

“Trident Studios St Anne's Court, an alleyway in Soho, London - was as anechoic as any studio could be. There were no reflective surfaces whatsoever (unless you wish to consider the upstairs control room's double-glazed window and drum-booth glass-windowed gobo). It was so dead that, when you shut the heavy door of the studio (thumm), your ears compressed. The 7ft Steinway piano was usually isolated with a heavy-duty ‘car cover,’ the lid being open at the low level, to allow for close-miking.

“The great rock / pop sound achieved there was thru' the genius of the Sheffield brothers, and the genius of engineers like Robin Cable, who was simply brilliant. He made drums sound bitchin¹ thru' his skills at tape-saturation. It was all analogue, of course; digital recording and effects were not even a twinkle in anyone's eye at that time!

“What we had there, to create ‘air,’ ‘atmosphere,’ was a physical echo chamber and a plate, which were the only reverbs available; all other delay, slap, and sfx- phasing (flanging) - effects were achieved with tape delays i.e. a second tape machine thru' which the main signal was fed.

“I called my friend and erstwhile fellow-student at the Royal Academy of Music, the accomplished classical and jazz pianist Ann Odell, to come and play the modular Moog synthesizer.

“So, as the listener can hear, my interventions as such are intermittent. Listening today, it's clear to me that I could have written more; developing the string orchestral compositions more extensively. Perhaps I was too ‘careful’ to not ‘interfere’ with the raw vocal / guitar. As I say, I can hear lots more that I could have written.”

“It's great that Leonard's songs have such long legs and have stood the test of time! He made a deep impression on me, and has my strong respect and regard.”

Despite promotional efforts by his Columbia record label, Songs of Love and Hate failed to dent the US Billboard Top 100.

In England, it reached number five in March 1971. The New Music Express headline declared “Morbid Cohen,” Melody Maker bannered “Leonard at his gloomiest,” while another British periodical Sounds ended their review with the words, “Delicious Masochism.”

Around this time Cohen gained a devoted Midnight Movie theater following in January 1971 after he read “What Am I Doing Here” from his book, Flowers For Hitler in the film, Dynamite Chicken, a collection of peace movement comedy sketches, clips, interviews and narratives written, directed and produced by Ernest Pintoff.

It stars a young Richard Pryor with appearances by Allen Ginsberg, Jimi Hendrix, Muddy Waters, Joan Baez, B.B. King, Andy Warhol and archive footage of Malcolm X. It was partially financed by John Lennon and Yoko Ono.

In May–August of ’71 there was the release of three movies all featuring Leonard Cohen music on their soundtrack—the German films Fata Morgana by Werner Herzog and Beware of a Holy Whore by Rainer Werner Fassbinder, and Robert Altman’s McCabe and Mrs. Miller, which incorporated Cohen’s recordings done for his debut LP with the Kaleidoscope: “Sisters of Mercy,” “Winter Lady” and “The Stranger Song.”

In one Melody Maker chat with Leonard, he explained the story about his recordings heard in Altman’s movie.

“Robert Altman actually built the film around my music. The music was already written, and when he heard it he wanted to ask me to let him use it. I was in Nashville at the time and had just gone to the movies to see a film called. Brewster McCloud.

"I thought it was a fine movie. That night I was in the studio and received a call from Hollywood. It was from Bob Altman saying he would like to use my music in a film. Quite honestly, I said, 'I don't know your work, could you tell me some of the films you've done?' He said MASH, and I said that's fine, I understand that's quite popular, but I'm really not familiar with it. Then he said there was a film I've probably never seen called Brewster McCloud. I told him I just came out of the movie and thought it was an extraordinary film, use any music of mine.”

Simon & Schuster in October 2020 published Leonard Cohen, Untold Stories by bestselling author and biographer Michael Posner.

The first of three volumes—The Early Years—follows him from his boyhood in Montreal to university, and his burgeoning literary career to the world of music, culminating with his first international tour in 1970.

Through the voices of those who knew him best—family and friends, colleagues and contemporaries, rivals, business partners, and his many lovers—the book probes deeply into both Cohen’s public and private life. It also paints a portrait of an era, the social, cultural, and political revolutions that shook the 1960s.

In this revealing and entertaining first volume, Michael Posner draws on hundreds of interviews to reach beyond the Cohen of myth and reveal the unique, complex, and compelling figure of the real man.

Posner is an award-winning Toronto writer, playwright, and journalist, and the author of seven books. These include biographies of novelist Mordecai Richler (The Last Honest Man, 2004), selected as one of the Globe and Mail’s top 100 books of that year); singer Anne Murray (All of Me, 2010, as ghostwriter); as well as books on medicine, film, public opinion, and money.

He was Washington Bureau Chief for Maclean's Magazine, and later served as its National, Foreign, and Assistant Managing Editor. Michael was managing editor of the Financial Times of Canada for three years.

Posner later spent sixteen years as a senior writer with the Globe and Mail, Canada's national newspaper. Two of his critically acclaimed plays were mounted at the Toronto Fringe Festival.

He began work on Leonard Cohen, Untold Stories in December 2016 documenting one of the world’s most respected music and literary forces in the words of those who knew him best.

In this absorbing and entertaining first volume, bestselling author and biographer Michael Posner draws on hundreds of interviews to reach beyond the Cohen of myth and reveal the unique, complex, and compelling figure of the real man.

Posner has really done his homework. I was honored when Michael and his editor at Simon & Schuster asked me and several other authors and poets to pen testimonial endorsements for the book’s back jacket cover.

“Posner is our Cohen-centric tour guide. He has delivered an enthralling oral history, carefully weaving the multi-voice narratives to us in a revealing, deep-dive exploration. I eagerly await the next volume.”

— HARVEY KUBERNIK, music historian and author of Leonard Cohen: Everybody Knows.

Michael Posner first saw Leonard Cohen read in January 1967 in Winnipeg, Canada at the University of Manitoba and later witnessed his 2013 Toronto concert.

In August 2020 I conducted an email interview with Michael Posner.

Q: What is the genesis of your Leonard Cohen book?

A: The genesis was actually the Mordecai Richler book. It had done pretty well critically, but not commercially. It struck me that Cohen was a much bigger name and was a book that could sell internationally. When I wrote him, about 2007, the only biography of any consequence was Ira Nadel’s Various Positions...but as you know, nothing happened then. He said no. I dropped the idea.

When he passed, Sylvie Simmons’ book was out—for four years— but I knew as a journalist that there had to other stories around. She had followed and fleshed out the familiar story line very well, but I knew there had to be hundreds of people who had stories or something new to say about him that had never been spoken to. The trick would be finding and persuading them to talk — hard, but less hard because he had passed

Q: What always drew you to Leonard's work? Your previous books are in other arenas.

A: I loved the music and the early poetry... but truthfully, I think my ambitions were journalistic. This was a guy of masks. He was very careful and skillful about his public presentation...Could some of those masks be stripped away? And what would be revealed? And would what might be revealed be connected to his work? So yes a fan, but that wasn’t the key.

At the beginning it was just instinct—there had to be more. Had to be. But almost as soon as I started, I realized there was A, infinitely more and B, I had taken on a huge challenge, not only because I was seeking new voices on Cohen, but because I also had to cover the known narrative as well — it is after all a biography.

So I’d need to find, if I could, new wrinkles even in the old stories. Sometimes I did, sometimes I didn’t. But with virtually every interview, I was coming away with new material. Not always home runs, usually singles, even bunts...but as it accumulated, I was confident that Cohen fans particularly, who can be obsessive, would want these stories—if I could find a publisher.

Q: And you embarked on this literary journey without a book deal, even schlepping to Los Angeles and other destinations.

A: Yes... Los Angeles, New York City, Hydra in Greece, Austin, Texas, London, England, Ithaca, New York a few times, San Francisco and Montreal several times.

Q: I happily turned over some leads to you that I didn’t utilize in my own Cohen book. I’m a record geek more interested in sound engineers, producers, studios and musicians and not the women, sex trips and drugs in my books. However, I am curious if the Israeli woman I recommended from the bagel shop in the San Fernando Valley in California was for real?

A: Yes, totally legit, but there’s a more interesting one in the second book.

Q: How did this book deal happen? Did you solicit a manuscript? A literary agent? I'm sure there were nibbles but there seemed to be a sense of destiny for the endeavor, let alone a multiple book deal for three volumes.

A: My initial proposal was initially rejected but then they changed their minds. And though they first said the full manuscript—then 600,000 words— would have to be cut dramatically, they changed their mind again and said let’s do three separate books so the cutting was minimized. I was hugely fortunate

Q: Even before doing additional research, further writing and editing the first book, tell me about some of your feelings and appreciation of Cohen's work before you really got going in the journey.

A: To be honest, I was not a student of his work before I began. I liked much of it, even most, but just as a fan, not any in-depth analysis... I did think that the first novel was largely autobiography, and that many of the songs were also, as he said of the song “Suzanne,” essentially reportage... the trick would be to decipher who is who in the lyrics… Because like most writers, he wrote what he knew...The three books, then just a single volume, were largely done when I got the contract.

I did develop a deeper appreciation for his work, his craftsmanship...his dedication, his genius...his ability to deploy the very specific to address the universal...the contemporary to reach the eternal.., and with humour…I do think many of the songs will last a very long time

Q: During the writing process, once the deal happened, and as you turned in volume 1, what changed or was really obvious now to you about Cohen as person and artist as a biographer?

A: Well, part of the answer is my appreciation for his gifts and his commitment to those gifts. On the human side, I saw a guy who really struggled...struggled with the consequences of fame on his life and art, struggled to keep pushing himself not to repeat himself... struggled, that is, to move the creative goalposts on himself... struggled hugely with relationships...his ‘marriage,’ his children, his many lovers.

None of this was easy...add to that his bipolar condition, which led to severe down periods...and you begin to see how complicated a life he led... he had trouble staying in one place...emotionally and physically... as soon as a sense of comfort or complacency or predictability was manifest, he checked out... and yet, for good friends, he was always there with time or money... and 95 per cent of the women he met, bedded and left, only speak in glowing terms about him and the positive impact he had on their lives. I think ultimately I came away with a sense that he’s impossible to reduce to one thing or another...he inhabited and expressed multitudes.

Q: What truly makes this book way different and essential for Cohenheads and the newly initiated? Why would Leonard appreciate your work?

A: The difference is two things. New stories told by people who we have never heard from before ...including some 20 woman he had serious relationships with...most in the later books... but also close friends like Barrie Wexler and Henry Zemel.

I think and hope that, were he still with us, Leonard would savor the ambiguity, and the conflicting accounts.

Q: You employed the oral history multiple voice narrative method in this book, which I do as well. I like bringing the witnesses to the forefront and let them recall specifics. What are the pros and cons of this methodology? Did you utilize this concept in previous books?

A: The oral biography format gives you Leonard as Rashomon...this complicated multifaceted personality who presents himself in different ways to different people. As though he could read the kind of character he needed to be and manifest himself as that.

The oral biography approach forces readers to make their own judgment about where the balance of truth might lie in any particular story or observation. The Richler book is oral biography as well. Its strengths are that it gives more weight and voice to people who actually knew him. There is no top-down, imposed interpretation of who Leonard was...that’s the good news ...the bad news is that the same virtue is a liability ...that readers might be confused by the myriad voices and the absence of a firm point of view.

Q: Can you give us some tips about the interview process for this book and your literary career? Is the secret to be a good listener? How do you get such good results? Also, is one reason because these yentas want to spiel on Leonard and really bring good stuff to the table?

A: Interview technique? Shut up. Don’t talk. Avoid the temptation. Listen. The more listening you do, the better the results. Also polite persistence—not everyone wants to talk, but with time and diplomatic overtures, some can be persuaded. The investment is often worthwhile

Q: What about the editing process?

A: Very complicated. First I had to transcribe the tapes… thousands of hours…so part of the editing occurred then...don’t transcribe what I won’t need. Some people appear once and some appear 30 times... so I had to locate where the quotes would go and then try to connect them to surrounding quotes as much as possible, being as faithful as possible to chronology. As to later edits, some ruthlessness was required.

In Studs Terkel’s oral biographies, there’s more fidelity to the particular nuances of individual voice. Here, for editing sake, I had to lose that individuality, mostly. Having three books obviously made the cutting much easier than it would have been with one....though it was still painful at times...

Q: Since his physical passing, and the Cohen tribute concerts in Montreal and celebrations, what has emerged in the Cohen universe? We know death of an artist beings new products and a slew of magazine and online tributes, documentaries as well as reissues and unreleased recordings.

A: Since his death: A posthumous book of poetry, The Flame and museum retrospective of his life that has toured internationally. A posthumous album of his music—words by Leonard, music by his son Adam and others, Thanks For the Dance.

There were plans for release of a book of early Cohen fiction/short stories, but that may have been delayed. Lots of Cohen tribute shows mounted internationally. He won a posthumous Grammy for You Want It Darker. There was Nick Broomfield’s documentary Words of Love, Leonard and Marianne, which has played worldwide.

Currently in post-production is a feature-length cinematic documentary biography that explores the song “Hallelujah,” directed by Daniel Geller and Dayna Goldfine. Cohen and Marianne are also the subjects of a feature film, directed by Paul Wiffen now being edited in the UK. Backbeat Books in May is publishing a memoir by Judy Scott, Leonard, Marianne, and Me: Magical Summers on Hydra. Two further volumes of Leonard Cohen—Untold Stories, the oral biography, will appear, the first in autumn, 2021, and the second in 2022.

Q: What about Cohen’s cultural impact?

A: There are two impacts to measure. The current one, on other artists, is huge -- Nick Cave, Bono, Rufus Wainwright...all kinds of people have been profoundly influenced by his work.

I don’t think the late tours per se are meaningful, except to prove how big a star he actually was... in effect, it was a five-year farewell tour and a celebration of everything Cohen. So, yes he was a kind of father figure, but not just in a reflexive, honorary way...artists will try to duplicate what he was able to do.

The other impact to measure is the future and it’s just too soon to say...but I do believe they’ll still be playing a lot of his music in 100 years...if the planet is still viable.

Harvey Kubernik is the author of 19 books, including “Leonard Cohen: Everybody Knows,” published in 2014 and now available in six foreign language editions. Kubernik also authored Canyon Of Dreams: The Magic And The Music Of Laurel Canyon and Turn Up The Radio! Rock, Pop and Roll In Los Angeles 1956-1972. Sterling/Barnes and Noble in 2018 published Harvey and Kenneth Kubernik’s The Story Of The Band: From Big Pink To The Last Waltz. For summer 2021 the duo has written a multi-narrative volume on Jimi Hendrix for Sterling/Barnes and Noble.

Otherworld Cottage Industries in 2020 published Harvey’s book, Docs That Rock, Music That Matters, featuring interviews with D.A. Pennebaker, Chris Hegedus, Albert Maysles, Murray Lerner, Morgan Neville, Dr. James Cushing, Curtis Hanson, Michael Lindsay-Hogg, Andrew Loog Oldham, Dick Clark, Ray Manzarek, John Densmore, Robby Krieger, Travis Pike, Allan Arkush, and David Leaf, among others.

Kubernik’s writings are in several book anthologies, most notably The Rolling Stone Book Of The Beats and Drinking With Bukowski. Harvey penned a back cover endorsement for author Michael Posner’s book on Leonard Cohen that Simon & Schuster, Canada published in October 2020, Leonard Cohen, Untold Stories: The Early Years)

This century Kubernik wrote the liner note booklets to the CD re-releases of Carole King’s Tapestry, Allen Ginsberg’s Kaddish, Elvis Presley The ’68 Comeback Special and The Ramones’ End of the Century).

In November 2006, Harvey Kubernik was a speaker discussing audiotape preservation and archiving at special hearings called by The Library of Congress and held in Hollywood, California.

In 2014 filmmaker Matthew O’Casey included Harvey in his BBC-TV documentary on singer Meat Loaf, titled Meat Loaf; In and Out of Hell, broadcast in 2016 on the Showtime Cable TV channel.

In summer of 2019, Harvey was interviewed for director Matt O’Casey on his BBC4-TV digital arts channel Christine McVie, Fleetwood Mac’s Songbird. The cast includes Christine McVie, Stan Webb of Chicken Shack, Mick Fleetwood, Stevie Nicks, John McVie, Heart’s Nancy Wilson, Mike Campbell, Neil Finn, and producer Richard Dashut. The premiere broadcast was in September 2020.

During 2020 Harvey Kubernik served as a Consultant on the 2-part documentary Laurel Canyon: A Place in Time directed by Alison Ellwood. Kubernik is currently working on a documentary about Rock and Roll Hall of Fame member singer/songwriter Del Shannon.

Kubernik also appears as a screen interview subject for director/producer Neil Norman’s GNP Crescendo documentary, The Seeds: Pushin’ Too Hard. Jan Savage and Daryl Hooper original members of the Seeds participated along with Bruce Johnston of the Beach Boys, Iggy Pop, Kim Fowley, Jim Salzer, the Bangles, photographer Ed Caraeff, Mark Weitz of the Strawberry Alarm Clock and Johnny Echols of Love. Miss Pamela Des Barres supplied the narration. Norman’s well-received documentary is scheduled for a debut broadcast on television and in various retail platforms during 2021.

This decade Harvey was filmed for the currently in-production documentary about former Hollywood landmark Gold Star Recording Studio and co-owner/engineer Stan Ross produced and directed by Brad Ross and Jonathan Rosenberg. Brian Wilson, Herb Alpert, Richie Furay, Darlene Love, Mike Curb, Chris Montez, Bill Medley, Don Randi, Hal Blaine, Shel Talmy, Don Peake, Kim Fowley, Johnny Echols, Gloria Jones, Carol Kaye, Marky Ramone, David Kessel and Steven Van Zandt have been lensed.